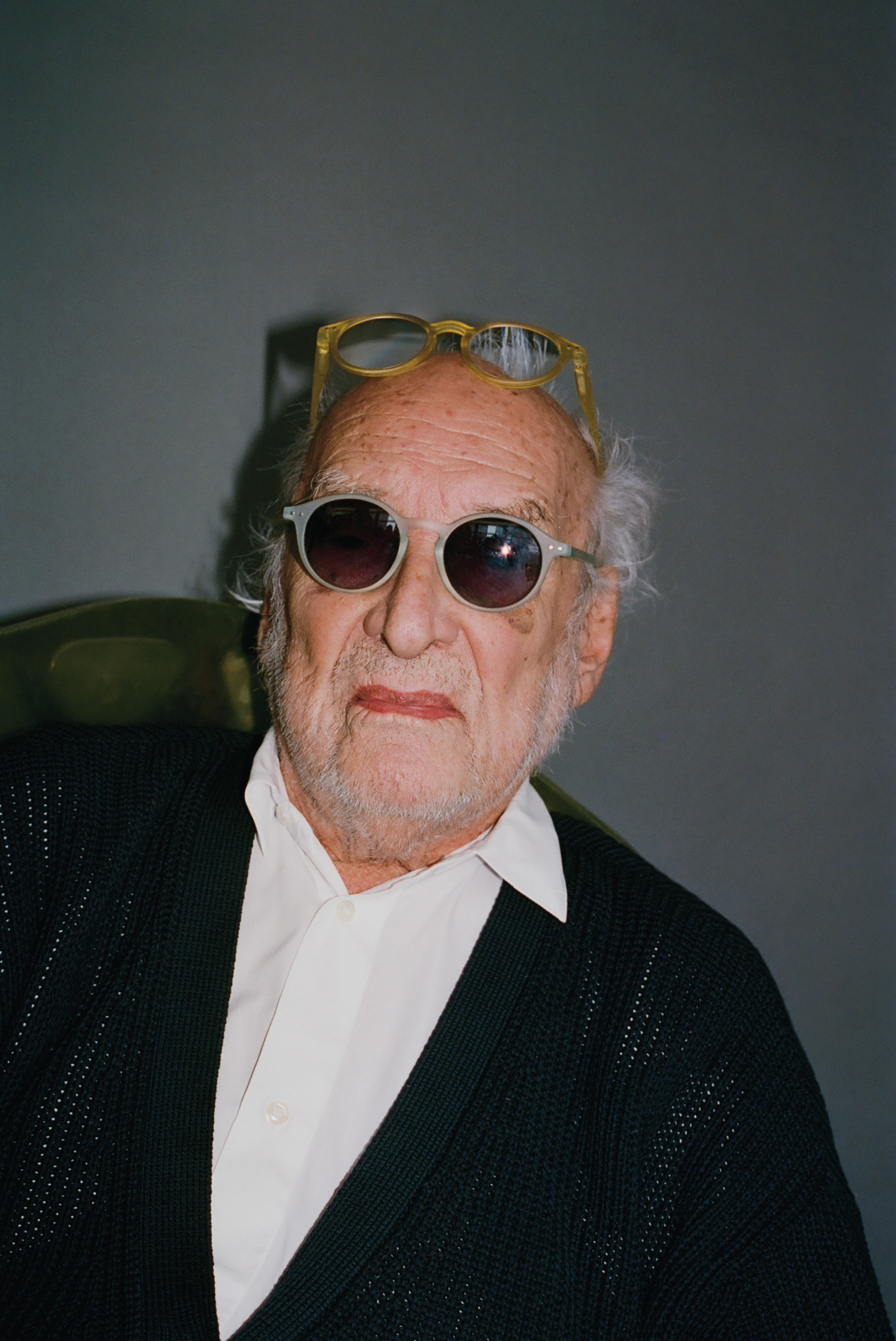

PS— What were your parents like?

GP— My father I never met because when he died I was only eight months old. My mother was a pianist and she taught me a lot about music, composition, why music represented time, et cetera. I learned a lot there. To me I was curious to know why an artist or pianist or composer is able to represent a special historical moment like Romanticism, like Impressionism. She explained why. She decided for me to go to architectural school because she said that that is where you learn the most important art, which is architecture. It is complex, strong, certain. I enjoyed it very much going to that kind of school.

PS— Did you have any really impactful teachers that stand out?

GP— The others were very mediocre, but I had one that was the History of Architecture teacher, and he was very good. He was able to talk about the past as if it were the present, explaining why a building created in the Renaissance had a certain quality. And he was talking about not the relevance of the style, but how to understand why an architect of the Renaissance was doing a certain architecture. He was able to explain what one had to do at this time. Kind of how to behave in our time, and what kind of architecture our time deserves compared to the past. So the school I went to in Venice was very good in this way.

PS— Do you have current plans to work on any buildings?

GP— We are doing a project that's a visitor center in the desert connected with a perfume company. I cannot tell any details …

PS— How do you approach a project like this?

GP— Everything starts with thinking, and I discover myself thinking quite a lot. Music helped me to think, to be innovative, to discover things, to use material that nobody uses — unfortunately for them, because it's very easy to work with my material, but nobody uses it. Thinking helps to understand our time better, what our time needs to be done, what we can do to allow the future to become present, and also have the present to become past. This kind of thing you can understand better with your thinking. And it's what I do. One important aspect of my work is that I don't like men very much because they are very boring. They're repetitive. They are a little tired today in general and I believe that it’s women who are bringing energy. Women have for a long time been obliged to stay in the private space, in the house, et cetera. Now slowly this is changing and this is very interesting. I believe there is a big crisis in the world because politicians are not at the level that they were in the older times. They are not doing the good for the places they administrate. They do the necessary for themselves and this is very bad. The world is in crisis for that reason.

PS— And women are the solution? I really loved Angela Merkel and Jacinda Ardern, the recent PM of New Zealand. I think they were extraordinary leaders.

GP— The future is that the women are moving from the private to the public and they are now working, as presidents, as leaders. The English lady, Thatcher. They are examples of great politicians who use their mind for the good of their country, not for the good of themselves. So this is one of the things I think about a lot, because I observe politicians and what they do in different countries is a disaster. Ukraine is a place with a lot of strange fascists, but they don't deserve for someone to make war on them. So I hope the women slowly take more and more responsibility in public life and they know how to serve better than men. The men in the older times did a lot of good things – important discoveries, communications. They invented things like airplanes, but today, they're tired; they play cards. They drink wine. I am not trying to see the future in this way, but I think in 100 years women will be directing public life better than men.

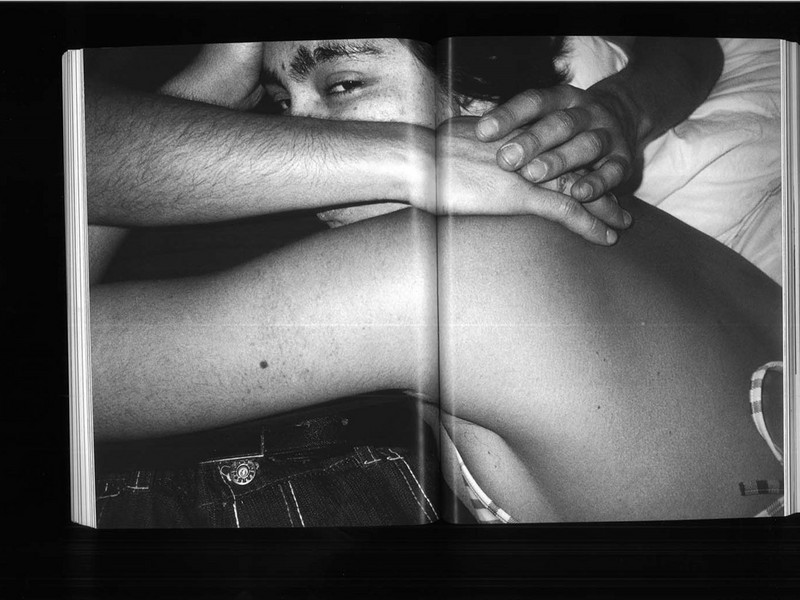

PS— Tell me about your book, The Complete Incoherence, and its title.

GP— Since I was 18 I’ve said I have the right to be incoherent: meaning, I say one thing today and I say a different one tomorrow. This is a way to be free and not to think always in the same way, like the military. I’ve always been incoherent and I’ve enjoyed that very much. Because I feel that I can experiment, and then say I was wrong.

PS— You seem very confident in yourself, very self-assured. Have you always been this way?

GP— I am not. I am totally insecure. Because the incoherence gives you insecurity. But who cares? Me, I am what I am. And so I don't want to say, "Look, this is the truth. Do this. It will be okay." No, I don't think so. Everybody has to learn how to swim. No regrets at all. Also because sometimes we say we don't like problems. No, problems are part of life and make your life interesting. If everything is easy — like in Scandinavia, where they have a very good administration, I think people are not totally happy. Where life is perfect, it’s also boring.

PS— Can you tell me about your proposal for the bridge project between Italy and Sicily?

GP— Someone proposed a project that looks like the San Francisco bridge. And I said, “Look, Italy is not a country that copies. It's a country who is copied.” And so I made my proposal, which is a bridge that is not straight from one point to another, but an S-shape. And there are 18 pillars, and you go with a train or with a car. Within the pillars, there are showrooms representing the 18 [20 minus the two on each side of the bridge] regions of Italy. Each has a hotel, a restaurant and a showroom inside. It's not that you go from one point to another in three minutes. You go because you stay in this hotel with a beautiful panorama at the level of the sea. It's what we are trying to show in Italy to make an exhibition. Not because I believe that they accept my idea, because it's too difficult. But at least I provoke people into thinking that there is a possibility to do a beautiful new idea of a bridge.

PS— I wish you could see more innovation like this realized!

GP— Yeah, sometimes I go to see art shows, and I find them a little superficial and the quality, nothing really innovative. I wonder if art is in crisis.

PS— When was the last time you saw an exhibition that you really loved?

GP— I don't know. I saw the guy in the London Museum of Art, who put a big fish inside liquid — Damien Hirst. You can show that in the Natural History Museum, not in an art museum. Or another one that I know personally is a guy who makes a kind of bean in metal, very shiny like a mirror. The people go and see the form and say, "That you do in the factory, not in the art studio.” There is very little meaning, because you don't need a lot of artists. In each era, three or four is already a lot. When I saw Duchamp for the first time – he's a great artist – there was a lot of meaning, a lot of ideas, a lot of innovation. We remember his work as something important; Duchamp took some industrial objects in 1919 and he put them in an art gallery creating a kind of scandal and a shock to let people know to be careful because the art today is related to the object, to industry. It’s like the Surrealist and the Futurist did. The Futurist celebrated the production, the machine, the noise. That was really an innovation, a movement. Today I don't see people so radical. If you ask me, I have no idea. Maybe I am ignorant.

PS— What does your home look like?

GP— It's a very simple place. Where I can live is a tool; nothing special — no style, no nothing — with a beautiful view of the water.