Paul Graham's Seasons

The Seasons will be presented in an online viewing until April 11 on www.pacegallery.com.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The Seasons will be presented in an online viewing until April 11 on www.pacegallery.com.

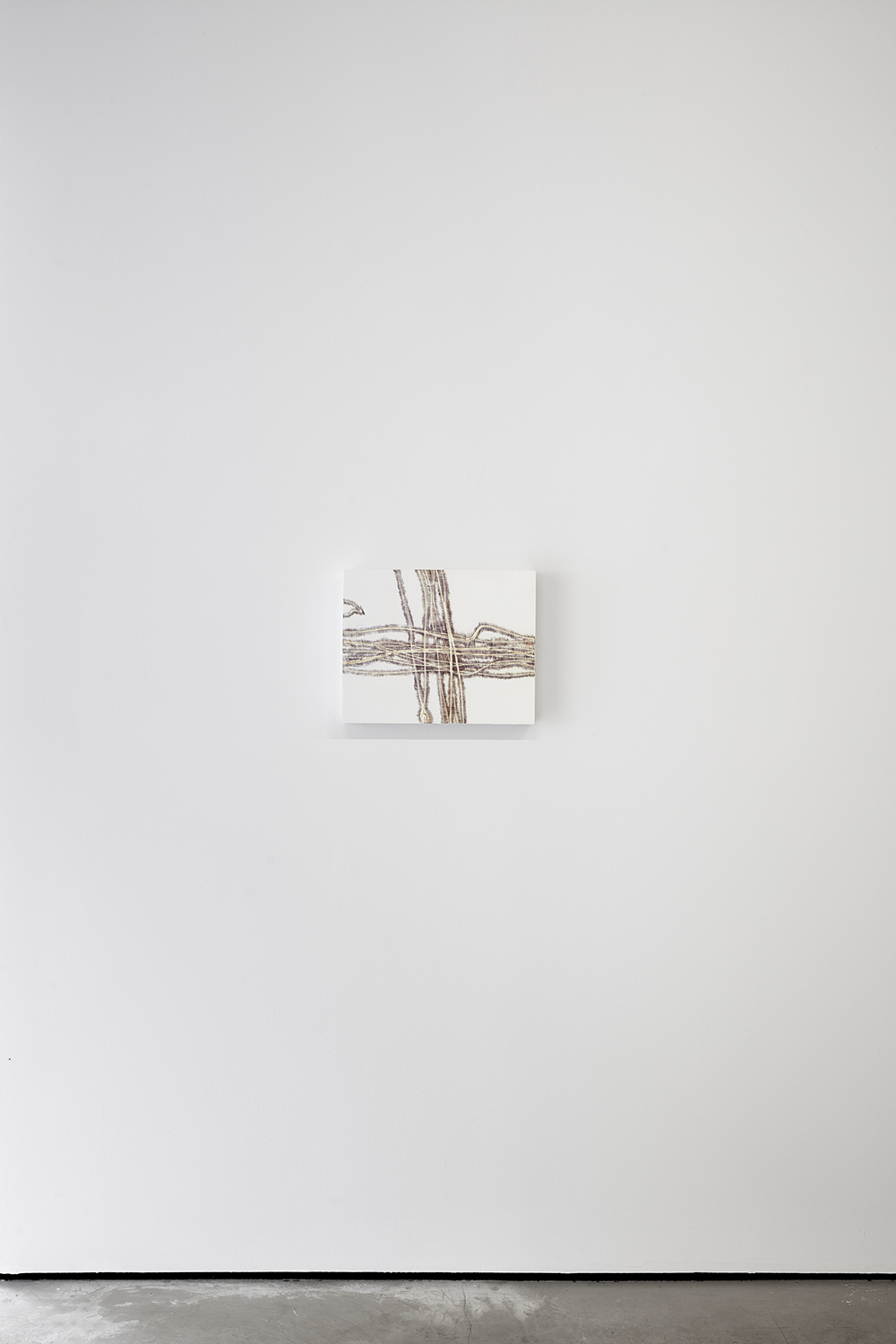

Her work, while somewhat abstract, is not true “abstraction” — the images Nguyen Quoc chooses to paint are what she calls “traces” — leftover, zoomed-in close-ups of photos she has taken. “Every day I see traces and images all around me, left by other people, by animals, by the passing and disintegration of time. My images and my gestures are common — basically I'm just a copyist, not a brilliant artist,” she says. “The better I choose my images, the better they will speak to viewers and (indirectly) put me in touch with others.”

The compositions are rooted in details, clues to where she has been and perhaps a map to where she is going. While their subject matter is indiscernible, they nevertheless “manage to relate to the viewer,” she says. “There is something common in them and in the way I reproduce them.” At first glance, it is unclear whether some of Nguyen Quoc’s works are printed images. Their flattish surfaces don't give much in the way of texture as paint often does. But upon closer inspection (which, Nguyen Quoc writes on Instagram, is recommended to view at “8 centimeters distance,”) alternate hypotheses on their constructions arise. Are they hand-drawn? The level of laborious precision is almost absurd.

Nguyen Quoc works mainly with humble materials — the show’s standout piece, also called Offering Body and Soul to A Radical Alterity, is a hand-drawn triptych made by using countless Bic ballpoint pens. To create the piece, Nguyen Quoc thrust herself onto the lifesize wood panel, surrendering herself to the work, and repeatedly drawing arcs that reflect the degree to which her arm was able to move back and forth. Imagining the petite, eloquent artist working herself both mentally and physically to her limits is truly awe-inspiring. As she speaks, a jumble of conceptual theory, anthropological terminology and scientific knowledge comes out in eloquent, well-phrased composition. Her paintings, similar to her way of speaking, dance between that exacting precision and free-flowing conception. Below, we caught up at her new show.

First off, can you tell me what grounds your practice? Is there a cohesive thematic element to your work?

Since the start of my practice, what has caught me and created a desire to inscribe something is what I call “leftovers.” That is to say, it made these traces that were not wanted, but in a clandestine way [are] a witness to the existence of life that were not represented. This remainder of something is not an object, nor a fragment, because we don't know what it is. It is something without body, which therefore has no iconographic language already inscribed.

Can you talk about the title of your show — Offering Body and Soul to A Radical Alterity? Were you influenced by Jean Baudrillard’s seminal text, “Radical Alterity”?

When I come face to face with a trace of an image that calls to me strongly enough to make me want to transcribe it, I will observe it and set up a whole protocol, like a ritual. I'll look for a gesture and techniques that will correspond to what I perceive. For me, the safest way to maintain a relationship with the world is not to interpret it, but to look at it factually and physically without ascribing particular meanings to things. In this position of copyist, I have to withdraw from myself to suppress my affect and fascination for the image. This is the only way that I can both understand the meaning of the image and also to encounter radical otherness — something that's absolutely not me. I think it is in this encounter with what's not us, that we can make the constitutive experience of humanity, that of coming up against plurality and differences without affixing our own desires to a thing.

What was your process for making the works for this show?

For this exhibition, I worked with the residues that my production and reproduction work had left around me. [For Drawing to Gathering Stars, these were], the patterns that emerge in the ink tubes of my empty ballpoint pens to the bottom of the ceramic cup in which I prepare my colors. It's the trace that I left when I produced other images. While making the color for that work, the pigment had left a thin film at the bottom of the cup, and I wanted to clean it by rubbing it lightly with a tissue. And when I lifted [it], this image appeared. I thought it looked like an image of a galaxy or an atom and its electrons. So we were going from the macro to the microscopic, and I had the feeling it was saying a lot about my work — at least the relationship we can have with it. I've been told that from far away it looked like a printed image. And once you get closer to the surface, it's like a whole world traced by mechanical hand. I think my work asks for this back and forth — moving away and then coming back to [it]. Because what we seem to see from far away is nothing.

Your process seems quite methodical and meticulous — there’s almost a scientific nature to it.

This is the most accurate way to translate the image without changing it. My images are sometimes outside the language of words. I'm often asked what they are. It's not that the question is not of interest, it's just that people see what they see. It's beyond my control. It solely depends on each person's lived experience. We can't necessarily put words on what we see. We can look at how it is done.

You clearly read and write a lot. How does language show up in your work?

There is a form of writing that is not made up of letters and words that can be read — humanity has always [done so]. We were reading the stars and coffee grounds and birds flying before language built and ordered the word. My work uses a more archaic language, the way we read the world around us, or the way we know that a river once flowed in what is now a dry riverbed. My gestures are mechanical, but a human action is never really mechanical. It's not just a matter of execution. Every technical action that I undertake is articulated by my sensation. The technical differences in my work are not stylistic effects, I simply have to adapt to the different iconography of my images.

Where would you say your influences come from artistically, or theoretically? Are there certain texts you refer back to?

Most of my influences are anthropological. My teacher, Dominique Figarella [at Beaux-Arts de Paris], is the one who told me, ‘you have to understand what techniques mean in your work.’ He advised me to read Marcel Mauss, who is the father of anthropology, and then I read Deleuze.

And how does that show up in your work?

The way in which [my works] are produced technically recalls ways of doing, psyches and lifestyle habits. [They] take on the human condition — the repetition and how we build our life and our psyches. They are not necessarily artistic gestures — they recall the gestures of an office worker or even a student at his desk copying something. Modernity pointed out that techniques participate in the experience of perception, and the question of language preexisted the distribution of signifiers.

What do you seek to get from your work? Or what is your relationship to it?

I wanted to understand the relationship with the viewer, because it's the only thing that puts me in relation with the world. I really wanted to be able to communicate and to understand why people are interested in my work.

In the press release for your show, it says that “if the thing seems to have potential for inscription, the potential to be a signal, then she works on it.” How do you know when there’s a “signal,” and the image you want to create?

I don't know, because my practice is not that domesticated. I think it's a good thing because I don't want to have to handle my work so tightly. I think this is why I draw things, because I try to understand the meaning of the image and why it was so strong to me. I had no choice but to make it. What I think will make me a good artist or not is to find the right images that will signal to people. Every trace can be a signal, because it is a trace of an activity. Homo sapiens evolved by reading the traces left in other spaces. We survived because we are able to read the traces in the world.

Your piece, Offering Body and Soul to A Radical Alterity is really incredible. It’s a giant triptych made from the humblest tool — a Bic ballpoint pen. Can you describe what your process for making it is like?

I trace [the lines] with many ballpoint pens. The size [of the strokes is] the size of the movement allowed by my arm. I discover my images only at the end. I put myself on it and I trace for hours. We can really know where my body was at the moment when I trace these.

What was the source material or image that it’s based on?

The image is a photo that I shot in school. It was a window ceiling covered in dust. Birds were falling on it, and their wings were scratching the dust. Light was coming through. This is an exact copy of the image. So this is not abstraction. It's a copy of what I saw — traces of birds who were falling because the window ceiling is not straight.

There's an element of masochism in the way you make art. You push yourself so far to create the image, it’s about seeing how far the work can go.

It's painful for sure. I'm getting a personal trainer who prevents injuries because I’m worried for my body. I work 12 to 15 hours a day. During my master’s degree, I came to the studio at 8 o’clock and I was leaving a bit before 9PM. So for that kind of work, I have kind of an urgency. I can't stop — I need to fulfill everything. The only thing that stopped me is my body. My work asks for time. If I want to produce a certain amount, I need to work a lot.

Offering Body and Soul to A Radical Alterity is on view at Gratin gallery until June 7 2024.

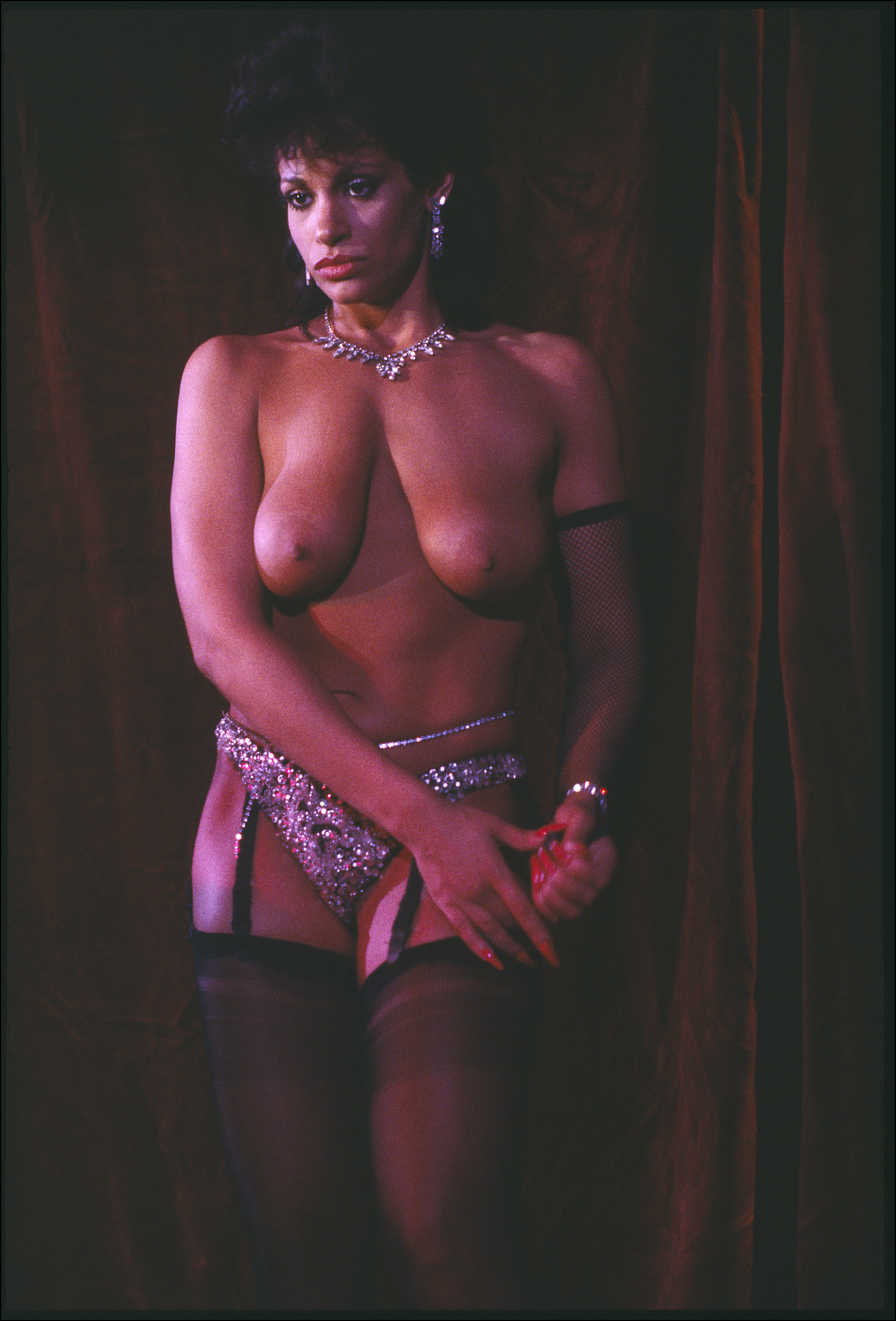

Throughout the show’s three month run, Nitke, who now teaches at SVA and works as a mainstream film photographer, has hosted several talks. On March 30, she and porn expert Casey Scott played clips from hardcore films that appear in American Ecstasy like Sexcapades (1983) and Viva Vanessa (1984), all by legend Henri Pachard. Nitke was his go-to photographer.

She entered the industry in 1982 through her husband, a financier who helped make The Devil In Miss Jones (1973). In 1982, Nitke started off as an on-set photographer working on Part Two. “I realized early on that I had access to this world, and I could do a documentary,” Nitke told me. “I saw it as an art project.” She struck a deal that she could pull slides, and did interviews on set.

“I did have a theory back then, that if you were going to do sex work, especially in front of a camera, you probably had a trauma in your life,” Nitke said, “which I totally disproved to myself.”

Every photo in American Ecstasy tells many tales, beginning in the stars they depict. One of the most striking shots in the show centers on Stacey Donovan, still fresh from Seventeen, riding her seated co-star reverse — her body poised mid-air precariously over his visibly glistening head. Donovan’s dirty blonde fringe obscures her downcast eyes, and the hands on her hips read defiant. “What I found interesting about her is she did not like sex,” Nitke remarked.

In White Women (1986), though — as we saw the night Nitke and Scott offered everyone an authentic porn dinner of soggy baked ziti — Donovan uses poppers to seduce a lovesick rockstar into fucking. She fakes an orgasm as he finishes, and when he promptly leaves, she desperately gets herself off. Nitke considers it a classic Pachard touch. She calls him “a sensitive guy who was also a shithead,” as well as a director who sought to portray female desire and experience.

Although porn migrated to meet LA’s pretty young starlets in the mid-80s, Pachard preferred seasoned performers like Sharon Mitchell and Vanessa Del Rio, both in American Ecstasy. One photo from Nasty Girls (1983) captures Mitchell before a moment of immense professionalism, where she improvisationally licked fluids from her necklace because her co-star accidentally busted outside of her mouth. Del Rio, seen flexing on stage, knew and demanded her worth.

These were hour-long films that fans had to leave home to buy. Although the plots that connected their sex scenes were flimsy, Nitke believes that if porn had been allowed to grow, it may have become an artform, like horror did. Instead, she witnessed prosecution from numerous angles — feminists like Andrea Dworkin, who saw porn as objectification and violence, alongside Jerry Falwell’s moral majority, who pushed the Reagan administration to pursue aggressive new venue shopping tactics while sticking obscenity suits on porn producers.

But, try as Mike Johnson’s “Covenant Eyes” might, vices prevail. For most who aren’t asexual or otherwise celibate, arousal is on the hierarchy of needs. And, like the rest of culture, the internet tessellated porn into infinite online niches. Some are exploratory and healthy, yet the wider machine says porn is giving teens hardcore tastes and dysmorphia. No wonder they’re not having sex. In a final blow of poetic justice, abstinence-only education IRL just makes porn more powerful.

Not that adults who had first kisses before Pornhub are much better off. I suffered when my middle school boyfriend called Megan Fox hot growing up, so the lover I brought to Nitke’s talk felt my hands sweat in his. Another colleague I ran into there walked out before it was over. We crossed paths again at a birthday party that night and discussed our various discomforts. In a world saturated with viscerally violent imagery, it’s fascinating that porn can still make people squirm. Nitke herself went through four literary agents and the illustrious editor Judith Reagan before self-publishing American Ecstasy in 2012 to avoid censoring its central hardcore stars.

As an exhibition, American Ecstasy encapsulates the fuzzy glamor of porn’s halcyon days. It can even get guests to check their baggage at the door by arresting them with the alluring abandon of a fledgling genre playing with the archetypal elements of sex, beauty and power, uninhibited.

The Alexander Gallery is haunted by the phantoms of the past. I imagine curating a show in a space like this is equivalent to checking in at the Chelsea Hotel, hosting a party at CBGD (impossible, thank you wholesale), or ordering the Bacon Burger at JG Melon. It’s a New York time capsule, nostalgically self-indulgent, and rightly so.

When you inherit a legacy like this, it’s easy to fall into the trap of repetition. At times, the motive behind this repetition is that of pressure, a sense of honor, or frankly, fear — the anxiety about living up to whatever was created before your arrival; the feeling of stepping into shoes too big but wearing them anyway. Sure they might walk you down the same path, but that's precisely the problem. Thus, one needs more than a microdose of either confidence or naivete to escape the dead end.

Chris Lloyd, I Shall Cut Off My Eyelids To See Better, 2024.

Cristine Brache, Blue Mood, 2024.

“You’ve got to have a serious ego problem to own a gallery,” quipped Alexander, ticking off the qualities above. He has an unsanitized perception of himself as a tastemaker. Nevertheless, his indifference prods the question: does every artist embody this trait? Underneath the imposter-syndrome’s standing reservation, which resides in every other creative, hides a desire to be looked at, to be perceived. Is that egoism or is it a survival instinct?

The outcome of the ego is not what defends Spy Project’s arrival in New York. Perhaps it is the fact that Brooke Alexander is indeed Pietro Alexander’s uncle, but it’s also more than that. Truth is that the exhibition stands independently, removed from the pressure of legacy. With ease, the space’s saturated history presents both established and emerging artists. Rooms are filled with creatives united in nothing but their allied urge — “need” as Apple puts it — to leverage the relics of New York’s post industrial landscape and channel it into not only their practice, but into their way of life.

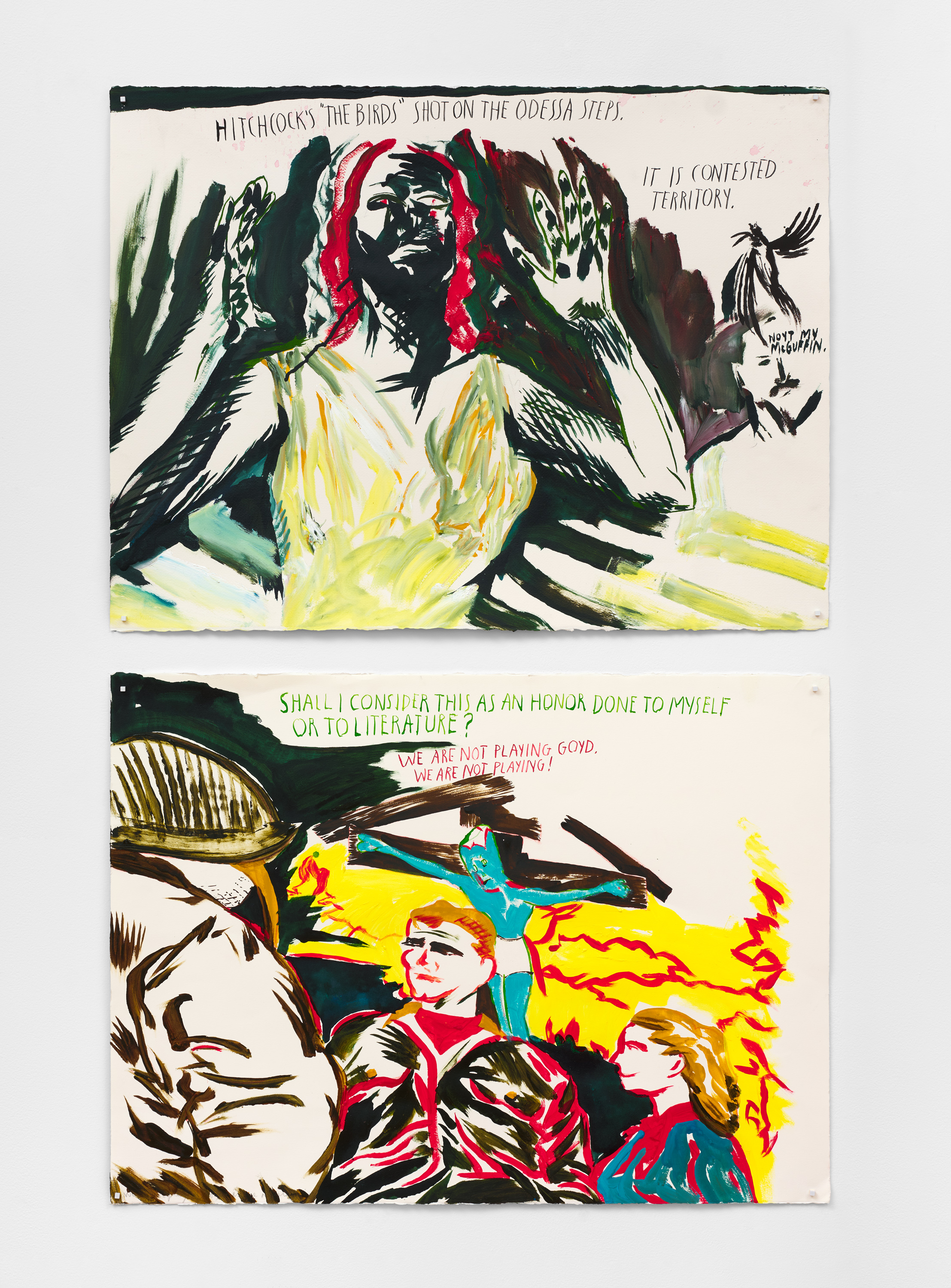

Raymond Pettibon, Untitled (Hitchcock’s “the birds”…), 2024. Untitled (Shall I consider…), 2024.

Katherine Auchterlonie, Feuillet-Beauchamp Notation of a Good Make-Out Session, 2023.

Kay Kasparhauser, Blood, 2024.

It feels like a family affair. The curation isn't trying to overcome some grand endeavour by suppressing the works under an artificial title. "Unrequited" is a title as blank as the gallery’s walls, granting them permission to tickle our thoughts again and again; (almost) all works are alike only in their differences — exception being the artist who sent in doubles, in which case the pieces aren’t neighboring, but placed at a screaming distance across the rooms, perhaps to provoke that very same tickling effect.

Textile collages by Alison Peery talk to Peter Alexander’s turn to velvet from 1984; Montana Simone’s pieces assert authority not only in scale but through their almost aggressive acquisition of steel while Kay Kasparhauser’s medium reads as hair, moss, and “Kay’s blood;”. Malik Al Maliki’s outlandish treatment of woodblocks tempers the violence within Raymond Perribon’s vocal acrylics, whereas within Sasha Filimonov’s panel — reminiscent of domestic Eastern European propaganda — the artist has installed a portable gun, which, when activated, is almost as arresting as the female figures concealed behind the thick layers of wax on Cristine Brache’s works. The effect quite literally blurs the line between dehumanizing and dream state.

Cristine Brache, Purple Bunnies, 2024.

Montana Simone, Choke Collar, 2024.

Sasha Filimonov, nightlight, 2024.

Unrequited is being at the library but only reading one page in each book. It’s scrolling Netflix but instead of watching one film, you pace through one trailer after the other. It's like being hungover at that brunch-buffet Sunday morning, suddenly finding yourself seated with a plate of croissants, bacon, bananas, strawberries, scramble eggs, yogurt, cream cheese, avocado, pancakes, ryebred, ham, turkey, Manchego, granola and roasted tomatoes…. But does it leave you overfed? Do you walk out feeling nauseous? A group show is always a slippery slope.

Spy Project’s New York debut isn’t mimicry as the mannequins at the flagship next door. It’s not imitating the legacy which it finds itself ensconced, nor is it posing for the sake of being seen. Unrequited sits you down for family dinner, where conversations traverse generations, opinions are opposing, and no one hesitates to voice their views.

Before I left the gallery on Wednesday afternoon, Apple pulled up the window to invite the neighbors smoking on the fire escape across the street to the opening the following evening. They looked like they’ve absolutely nothing in common yet there they were, making sense in one another.

Spy Projects, a contemporary art gallery in Los Angeles founded by Pietro Alexander in 2021, is temporarily visiting New York. The exhibition, Unrequited, will be on view through May 31st, 2024, at 59 Wooster Street.