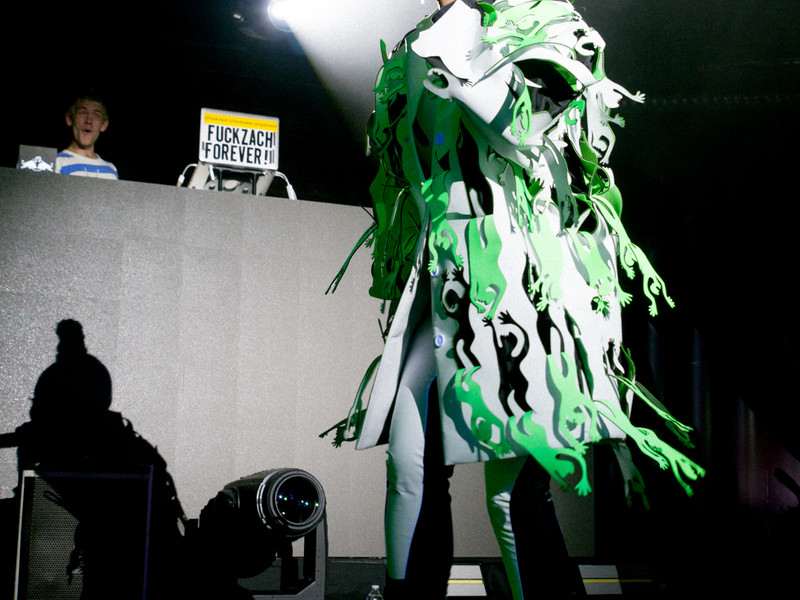

Pauli Cakes and Omari Love’s Opium Angel

The name Opium Angel sounds euphoric, yet mortal — a paradox that seems to capture your sound perfectly. How did you come up with it?

Omari Love— The first two letters of “Opium” are like “OP” for Omari and Pauli, but opium is also a drug that makes people feel really good. Euphoria is a good word, as you said, but it also destroys — that’s the mortal aspect I felt from it.

Pauli Cakes— And in a way it's like dying and coming back to life through ecstasy. Opium makes you feel euphoric, but if you do too much, you die. Then, you reincarnate into the world as an angel. The music isn’t dark, but it talks a lot about existence, deconstructing it, eating the body, bleeding, and then coming back — like the line going flat on a heart monitor. It definitely deals with mortality.

Pauli, as a New York native, how has your upbringing inspired your artistic approach? And Omari, coming from Minnesota, how has your background shaped your music, and what has been the impact of moving to New York?

PC— Growing up in New York, I’ve always been surrounded by different sounds. Music has always been my form of escapism in an overstimulating society. I have a very maximalist approach to sound because, in New York, there's always a million things happening at once. Growing up in the Bronx, I was constantly exposed to diverse music, like dancehall and futuristic Caribbean sounds. These sound bites have always been in my head.

OL— Growing up in Minnesota, there was always this battle between West Coast and East Coast music, but being in the Midwest, I was exposed to both. My dad loved West Coast music, so I grew up listening to a lot of that. For a long time, I didn’t listen to any East Coast rappers because I thought West Coast was the best. Knowing Prince was from Minnesota was also a huge influence — it was so unique, like nothing anyone had heard before, and I wanted that in my music. As I got older, I realized that every place has its own sound, and when I started creating music, I became a sponge to all of it. Moving to New York exposed me to things I didn’t even know existed, like noise music. Seeing artists like Deli Girls and Machine Girl was mind-boggling to me — it was so unconventional and inspiring.

Your EP has a strong political theme, especially on tracks like “Metallic” and “Need to Move.” There was a deep movement-based vibe to the lyrics. Could you expand on those messages a bit?

PC— For “Need to Move,” the line “abolish me, abolish you” comes from deconstructing the self — like, fuck my ego, fuck your ego. It’s about abolishing oneself and others, getting rid of the things that drag us down, like ego and authority. Nothing belongs to us, nothing in this world belongs to anyone — we inherit everything from those who came before us. The song is about abolishing it all and feeling the music, feeling the rage, without being trapped by ego or physical constraints. It’s like, “Fuck me, fuck you, we’re all pieces of shit, so let’s just dance and feel it.” Let’s just dance and move and feel it and not try to exist on some weird moral hierarchy.

OL— The EP was recorded during the time of George Floyd’s death and the protests that followed, which were focused on abolishing the police, the government, and the systems that oppress us. We wanted to engage in movements outside of ego. Whereas now, we’ve become kind of stagnant and almost regressed into this hyper individualistic society that depends on capitalism to move forward. Those songs speak all to that. I wanted to engage in movements outside of ego — to start understanding abolition and deconstruction, we have to abolish ourselves, our egos and unlearn the policing thoughts that live in our minds.

To me, art should be true to the artist while inevitably reflecting the time of the world they live in. I’d say you accomplish that here. What do you want people to learn from listening to your EP?

OL— The most important ideology I have is expression. People should absolutely express themselves and not let that be taken away, watered down, or diluted.

PC— When people listen to our music, I want them to understand that we’re attempting to break down binaries. We don’t care if a song doesn’t sound “professional” or “acceptable.” It’s about deconstructing sound and invoking inspiration and rage in people’s hearts.

OL— My view on expression is rooted in imperfection. That’s incredibly important to me — I’ve accepted that I’m not perfect, and no one I know is. The artists I revere most are fundamentally flawed, and that’s an important aspect of our music. It’s not perfectly mixed because I didn’t go to school for audio engineering — I don’t know music theory. Anyone can make music; you don’t have to be classically trained.

Who inspires you musically, and who did you channel while creating this project?

PC— For “Eat the Body,” the line “eat the body, drink the blood” has a Catholic undertone related to communion in Church and more generally, guilt, but I was also thinking a lot about my own religious and spiritual practices. What sacrifice means to different spirits in order to maintain relationships with them — in Santeria there’s a lot of blood sacrifice for spiritual rebirth, our loved ones, etc., constantly. Listening back to the lyrics, I felt they were very inspired by 5)/5 and my veneration for my ancestors and dead people that I work with and talk to.

OL— My aunts were the first to inspire me to make music — they had a duo called Double Shot, which was gangster rap. Seeing my aunt Tiffany’s home studio was so inspiring to me. Rappers have always been my biggest inspiration, especially in their poetry. There’s a quote from Tupac in an unreleased interview that came out in 2015: “We’re not really rapping; we’re just letting our dead homies tell stories through us.” At first, I didn’t understand it, but the more I made music, the more it made sense. It’s like there’s a collective, ancestral consciousness speaking through us, communicating very important messages.

I think music carries a lot of energy, which is what makes it so relatable — everybody’s felt the same in some way or another. What were some of the perks and challenges of working together?

PC— Everything we do together is a byproduct of our love and individuality, but also our unity. I think that’s really special. We both contribute our unique experiences and perspectives to create something mind-blowing and it never ceases to amaze me. Omari inspires me in every sense, and their production is incredible. Both of us being non-binary and having a deconstructed perspective on sound and music created this sonic bendiness that doesn’t really fit into any one experience, which is such a special advantage to what we do.

OL— Pauli has introduced me to sounds I wouldn’t have tried on my own, which is the cool part about Opium Angel and our collaboration. It’s like raising a child. In the beginning, it didn’t feel like a responsibility; it felt like something that came together naturally. That’s what music and expression are about — it shouldn’t feel like labor; it should feel like expression.

PC— Coming from different musical backgrounds — Omari with production and me with DJing and working with pre-made sounds — sometimes we butt heads because I can be impatient. The musical process takes a lot of patience, as I’ve learned from Omari, and it’s not like a DJ set; it doesn’t work like that.

Both your vocals carry a unique and enticing pitch, and the beat is dense and heavy, yet relatable. Having successfully merged a niche sound with public appeal, what are your end goals for this project, and where do you see yourselves after the release?

PC— I don’t want it to end; I want it to keep going. I want Opium Angel to be part of a larger musical archive that people can reference throughout time, history, and culture. I want the project to grow, and for us to create more bodies of work. Eventually, I’d love for us to have enough resources to record in a proper studio, because right now, everything is recorded on our computer.

OL— I want to continue developing a body of work and dive into more visual aspects, like recording videos and incorporating visuals into our performances. I’d love to perform all over the world, take our project everywhere, and collaborate with other artists.