Rankin Goes Back in the Dazed (1991-2001)

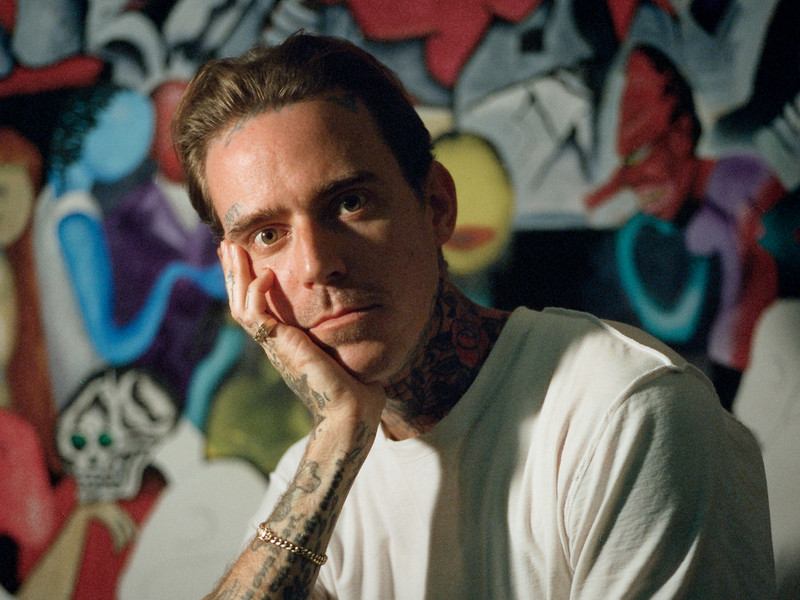

office spoke with Rankin over FaceTime about Back in the Dazed, the first retrospective in the UK showcasing his early work from the 90s. We discuss nostalgia, the ethics around shooting your subjects and critical analysis in portraiture. Don't judge a book by its cover, but what about magazines?

How did the idea for your retrospective come about? What inspired this timing?

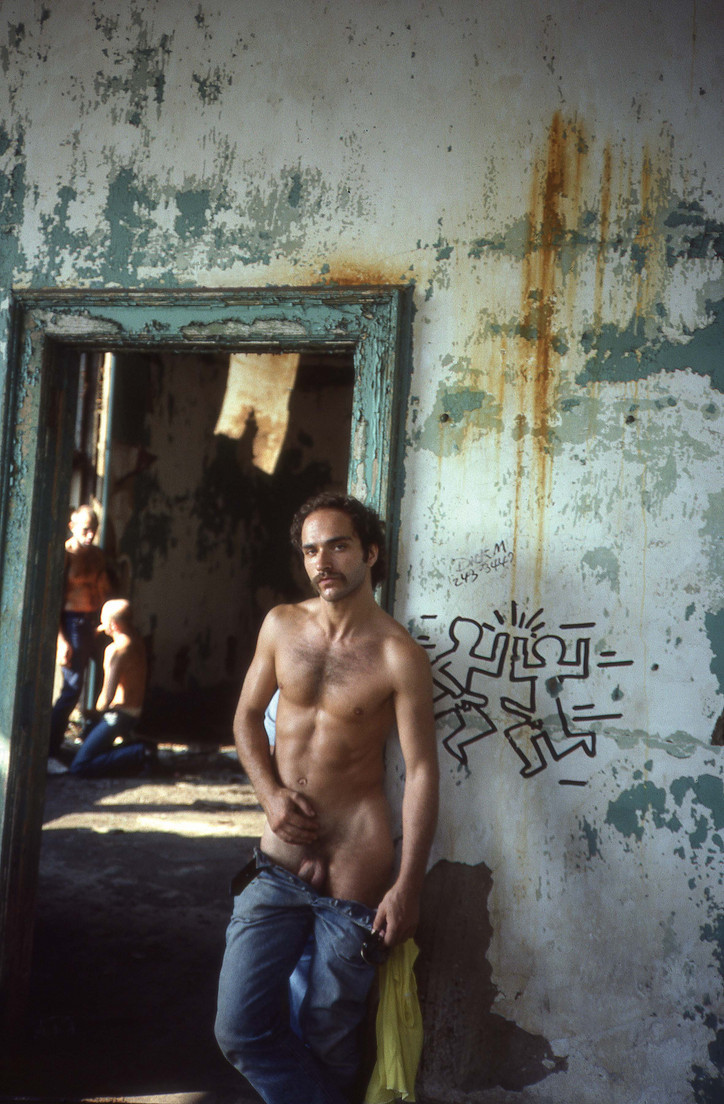

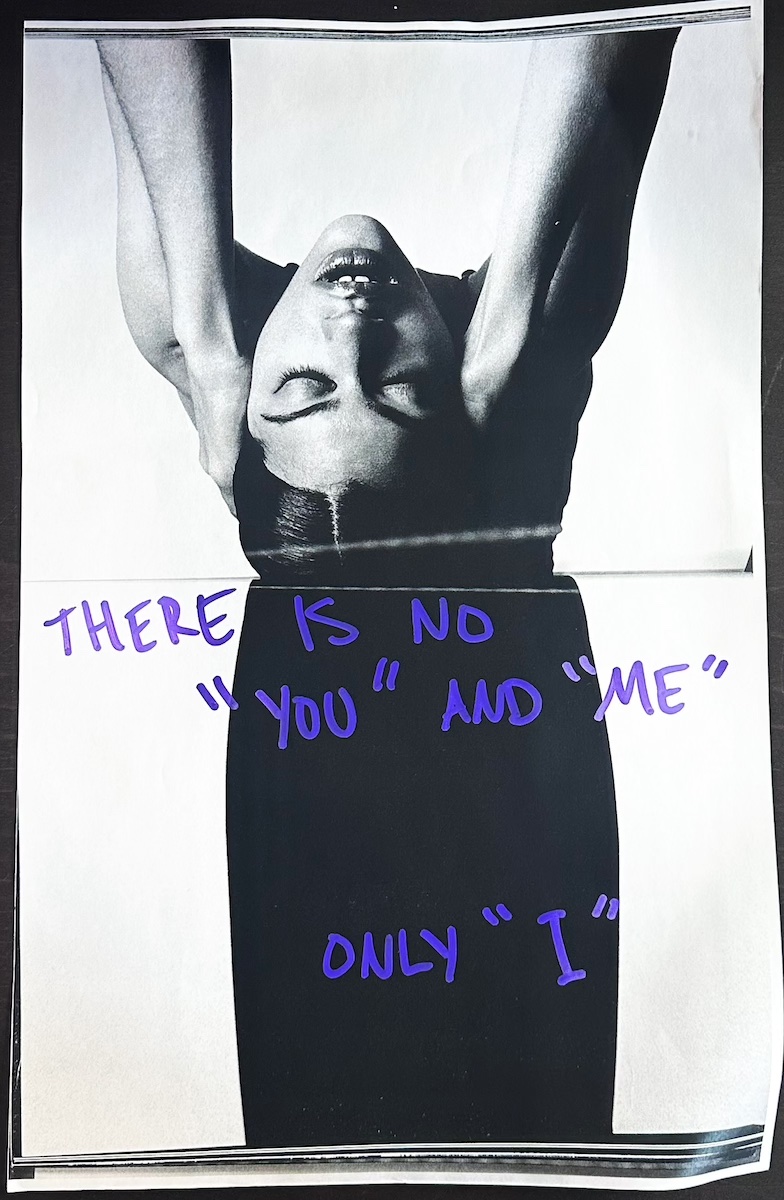

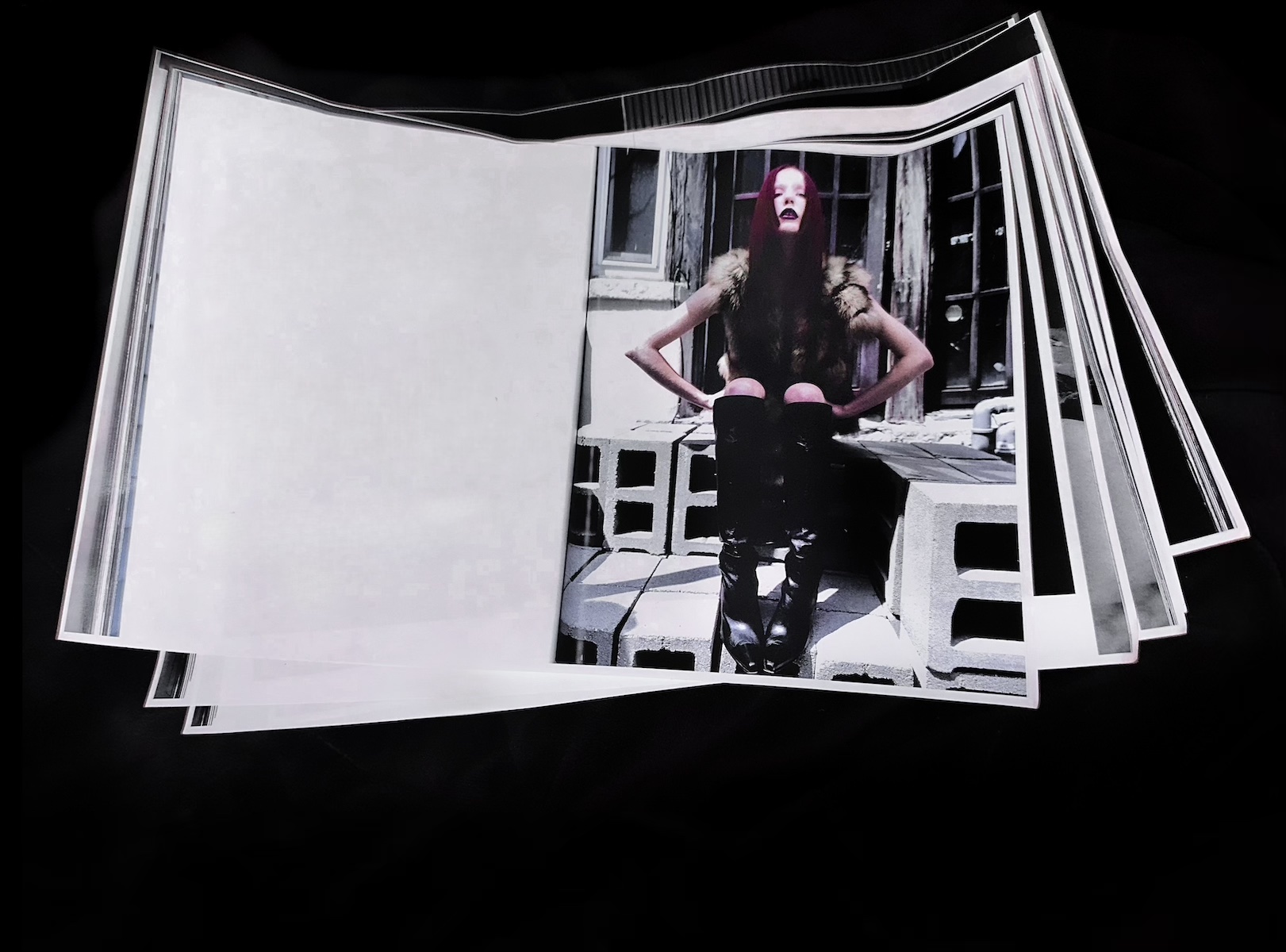

Dazed started over 30 years ago and it just felt right, really. Last spring, we had a show called Dazed Decades. It was a really great, beautiful show but people were more interested in the 90s. That decade was the most groundbreaking work in terms of pushing the boundaries. Our photography was very different from other magazines.

I didn't really do any of my famous work from the 90s for Dazed, so my stuff here is specific and more experimental and exploratory. I was 24 when we started doing Dazed. It's quite mad when you think those photos are photographed by a 24-year-old. I was 34 by the end of it. In this show, you see the progression of me and the magazine. I started not being able to afford to shoot or print in color and you watch me grow up as a photographer. Few photographers become successful at that age, unless they’re coming from modeling or generational creativity. We all came from non-creative families. We got together at college, did a college magazine for three years, then did Dazed. I started doing magazines at 20, that's the maddest thing. Jefferson [Hack], the editor, was 18 when he became the editor of Dazed.

I read that at 28 (nearly how old I am), you laid out all the covers of Dazed you shot, put them on the floor, and thought to yourself, how good your life was. After shooting so many icons, what is it like to revisit those early covers? Does it feel nostalgic? Do you feel more critical of your past work, or mostly proud?

Good question; it changes a little bit. I did a book six years ago about the work from Dazed called Unfashionable. It combined my work in fashion, art and photography. When I looked at that work, it was quite basic technically but I was surprised it included the same themes. The human condition, the manipulation of imagery and media, the idea of taking celebrity and trying to democratize it and make it more accessible. I'm fascinated by the seduction of fashion and trying to make it more human. Those have been the same themes in my work for 35 years. I didn’t think that — until I looked back and went, “Oh God, I'm still banging on about the same stuff.”

Of course, I'm critical. A lot of current work lacks critical thought behind it. I don't mean that just in terms of looking at it and thinking “Is it good or not?” but thinking, “What's the meaning of it in the world?” When critical thought is in the work, you can feel it, \you don't need to ask. It's in your face. I've got that. It's built into me. I'm a 51% positive, 49% critique. You criticize me, I've already done it.

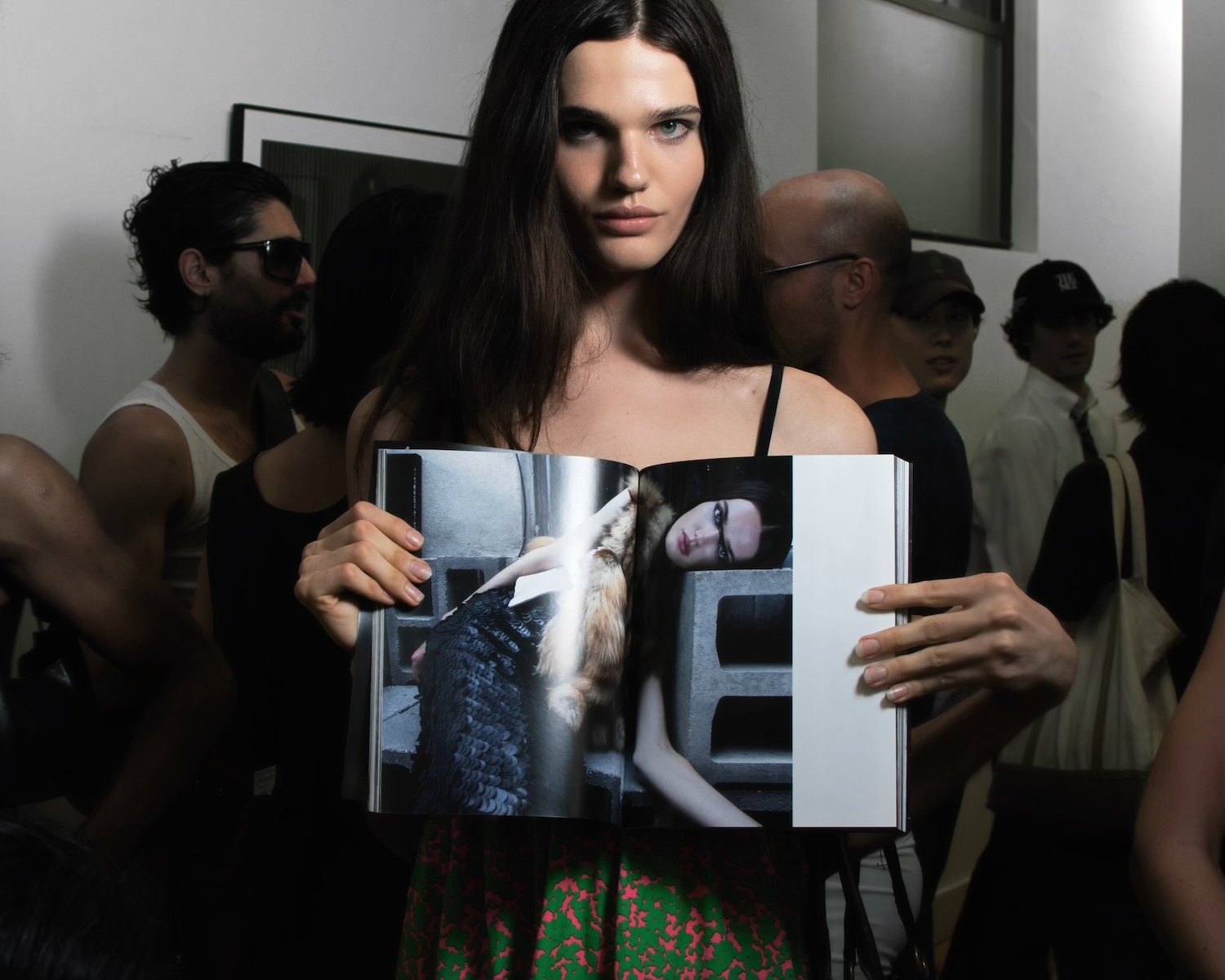

But I've enjoyed putting [the retrospective] together and looking at all the collaborations. I took them for granted then, but now I see how special it was. So many people in the photos or contributing to making the photos came to the show and it was overwhelming to see them all there. I’m not in touch with these people all the time, giving the work credibility beyond me and my relationship to it. I'm frustrated I didn't have a better relationship with some of my collaborators, but that's the arrogance of youth.

What’s it been like interacting with people at the retrospective who haven’t been reading Dazed for the past 20 years? It’s a magazine for youth culture but a lot of 18-25 year olds weren’t even born for these issues. I would love to know what it’s been like for you to witness their reactions to your work.

I have to be honest with you, I haven't really watched people look at it, but I’ve seen the social media response. I use social media to represent my work, not represent me so I'm not constantly on it, being performative. It feels like talking into a vacuum, but it’s been fascinating to see people post about [the retrospective]. People have their favorites and there's something affirming in that. The age range of people reacting to it is broad. I made this work when the magazine was distributed to 5,000 people. By the end of the 90s, we reached millions of people. But by that point, I was drifting away. Dazed was becoming less political and more commercial as a fashion and style magazine. I was more interested in changing things.

What was it like to watch Dazed become something on its own? Do you still feel connected to the magazine?

No, not really. But the ethos now is very similar to the ethos at the start. When we started, myself and Jefferson [Hack] made an agreement that we wouldn't be the editors once we felt like we weren’t the target audience or relating to the target audience anymore. We always said that you should make a magazine for yourself, not for your audience. Then the audience will come, but the minute the audience isn't relating to you, you need to move on. That's why he started AnOther and I started Hunger Magazine.

If you said to them I left because it became commercial, they'd say I was the person that was good at making money and commercialized lots of it. We sold the back cover and I would shoot it. That was completely commercializing but we did it in a unique way nobody had ever done before. Back then we were about creating culture, creating moments, creating what I guess you'd call “breaking the internet.” We were never about reporting or taking photos of culture. We were making it. We started Dazed to be a platform to voice independence, unique thinking and youth. I love it when it still does stuff like that. I'm proud and jealous all at the same time.

Exactly. I love bits of it. There are times when it feels like rinse and repeat. But when you leave something, you leave it. You should never be the back seat driver. I let it go seven years ago. I like to watch it from a distance and hope that they do well. It’s a bit like watching your grown-up child fuck up sometimes or be really successful.

We were international in our outlook. We never thought about just Britain, just England, just London. We always wanted to reach more people. Jefferson was the reason we were one of the first magazines to have a website, do broadcast publishing and have a TV show.

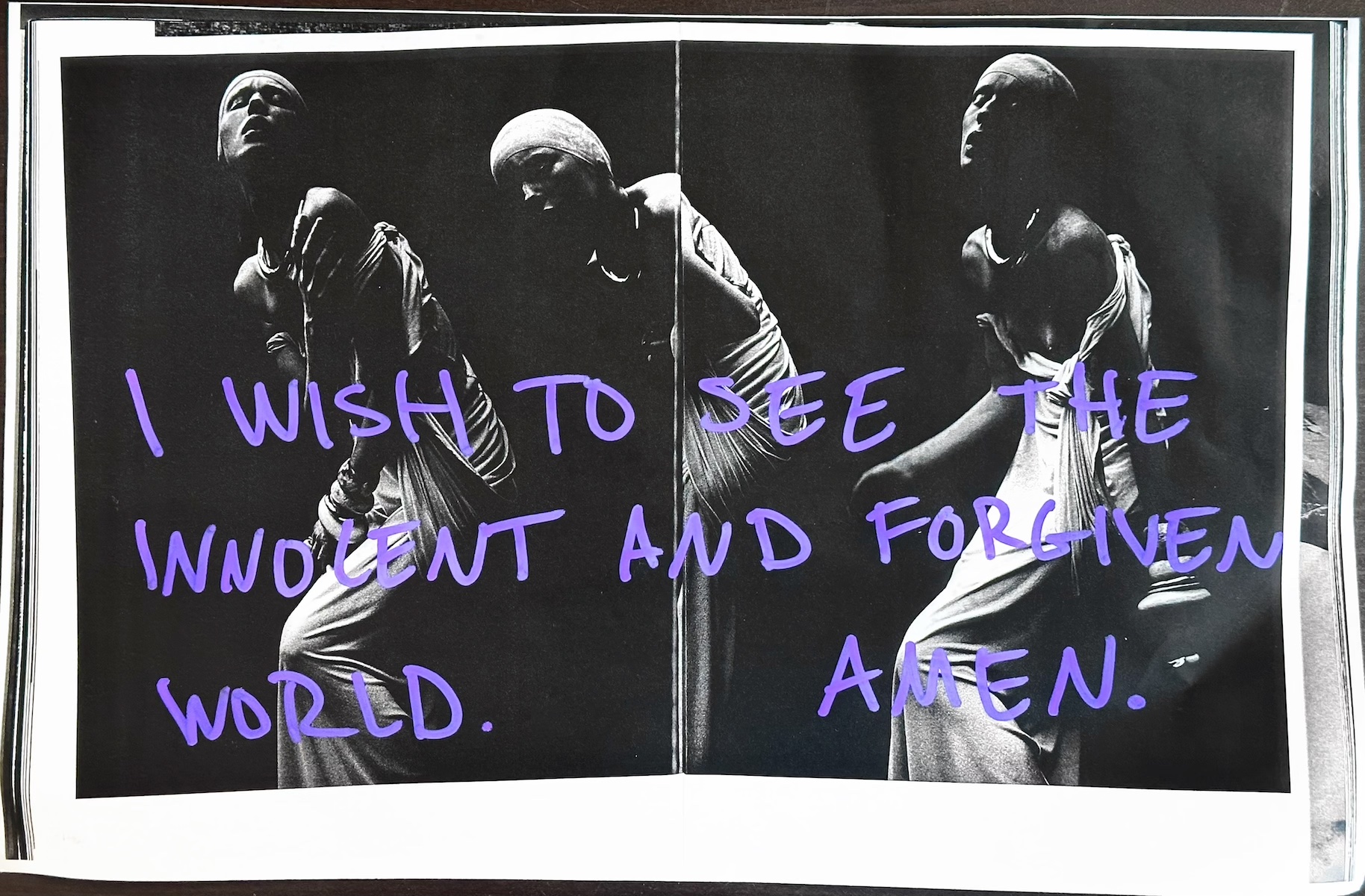

A lot of the things that Dazed talked about preempted a movement in purpose or in identity. We were talking about fluid identity and representation and equity back in the 90s. Vice never did that. They did drugs and parties. We've been criticized for being party kids too, but we were never trying to be sexist, racist or laddish. We were interested in art, culture and music. I read recently the reason Vice failed was because they tried to change with the times. The one thing you should never do is try and change with the times. You should always stick to your unique view. Dazed had that early on. We didn't trust the platforms.

When I left, I just wanted to be a photographer again. I was like, I'm done arguing. I don't want to debate what's going to go in the magazine. I don't want to have to chase the pages, having the fight about if you can get a cover. I got really tired of it. Also, we changed. I always like to think of this as a band. At the beginning of the decade it was just me and Jefferson. By the end, the band had decided to move on and have solo careers. We put a new band at the end of the 90s and I didn't fit in, really. Life goes on, you just have to let it go. It’s a bit like Fleetwood Mac. They have 25 incarnations.

Frankly, we became too successful. We started as kids at college and by the end of the 90s we all became successful on our own. Most of us continued to be successful. It's like not one of us gave up and left to become a gardener.

It always makes sense in retrospect, but in the moment, it must feel like a lot of risk and uncertainty.

We never thought we'd survive more than a couple years. The drive and ambition we brought to [Dazed] was about that early 90s opportunity. A lot of people who hit the 90s wanted success and took lots of risks. We had just come out of recession. They were like, why not? What have I got to lose? I look at that moment now and I'm proud we were there and did it.

For me, the purpose of photography is to reveal, and be a window into a world. But by the time I was becoming a photographer, that insight from the fifties, sixties and seventies with Life Magazine and Picture Post in the UK was almost over. Don McClellan had been around for 30 years — I never thought I could be as good as him. It felt pointless. My dad said to me, “Do something you're good at. Don't fight against what you are good at.”

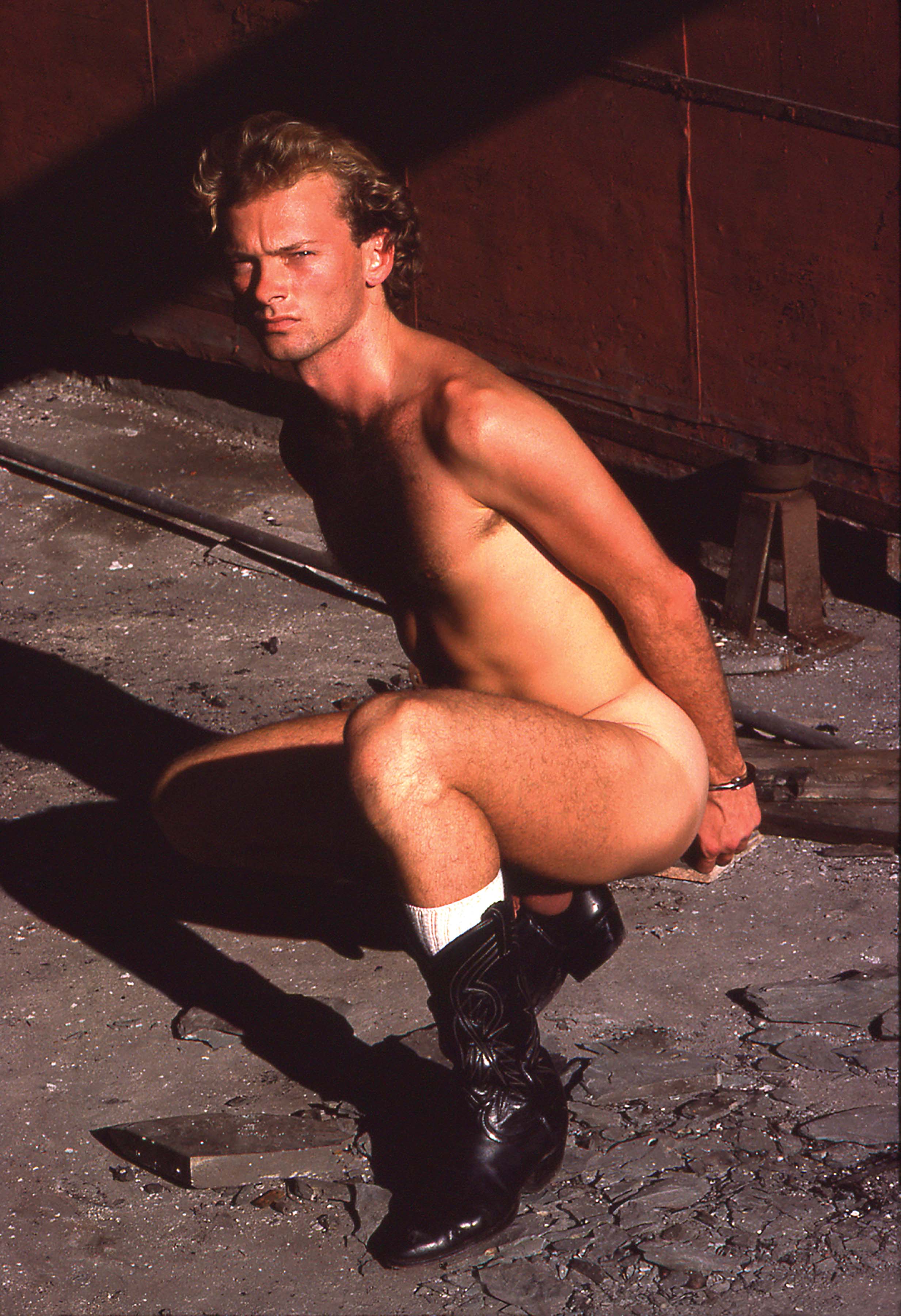

I was good with people. I realized quickly it was my strength. Documentary was not my skill, but I wanted to talk about societal problems and create insight on it. I thought this through when I was 20. I was doing a degree in art photography, but I was also making a magazine. I was looking to communicate thoughts and ideas I had when I wanted to be a documentary photographer. I’ve always wanted to make work that changes the way that you look at photos or what the photos are about, to break down preconceptions about identity or race, even though I did art photography and portraiture. I was seduced by it.

I’ve heard a great quote, “If you're a really good photographer, you generally love your subject.” I loved my subject, whether that was a portrait of somebody famous I was trying to make more revealing, or a fashion shoot where I was trying to say something. You can tell that I loved it.

But when you take a photograph, you have a responsibility to yourself, to the subject and to the audience. Even if you're doing a commercial image, you have to have an understanding of what you are doing, why you are doing it, and how you can defend yourself to critique. I don't have a real belief in what is right and what's wrong for other people. I just know what's right and wrong for me. And consent around photography is so important. I ask for permission to take the photo, put the photo in a show or in a book or in a magazine. I include the person in editing the picture. I've been doing that for 30 years. When people say no, I respect it. I get annoyed, but I still respect it.

When you think photography is a feeling or capturing a moment, it becomes dangerous. People with cameras go, “Oh, it's art, because I say it's art.” Well, I don't really believe it's art because you say it's art. You can have what's called an eye, and a perspective. But where's your thought? Have you considered what damage or meaning is within that? Have you thought about your audience? If you're making it for yourself, good for you. Photography is an incredibly powerful medium, so it's easy to misuse it or to be too casual. I love the proliferation and democratization of photography, because we can all hear it, see it and speak it because it’s not politically held back. Everybody has the ability to look at something unless they're blind. Add filtering and programs or apps to make massive changes, it’s a whole other thing. That's exciting, but scary. I don't take photography casually.

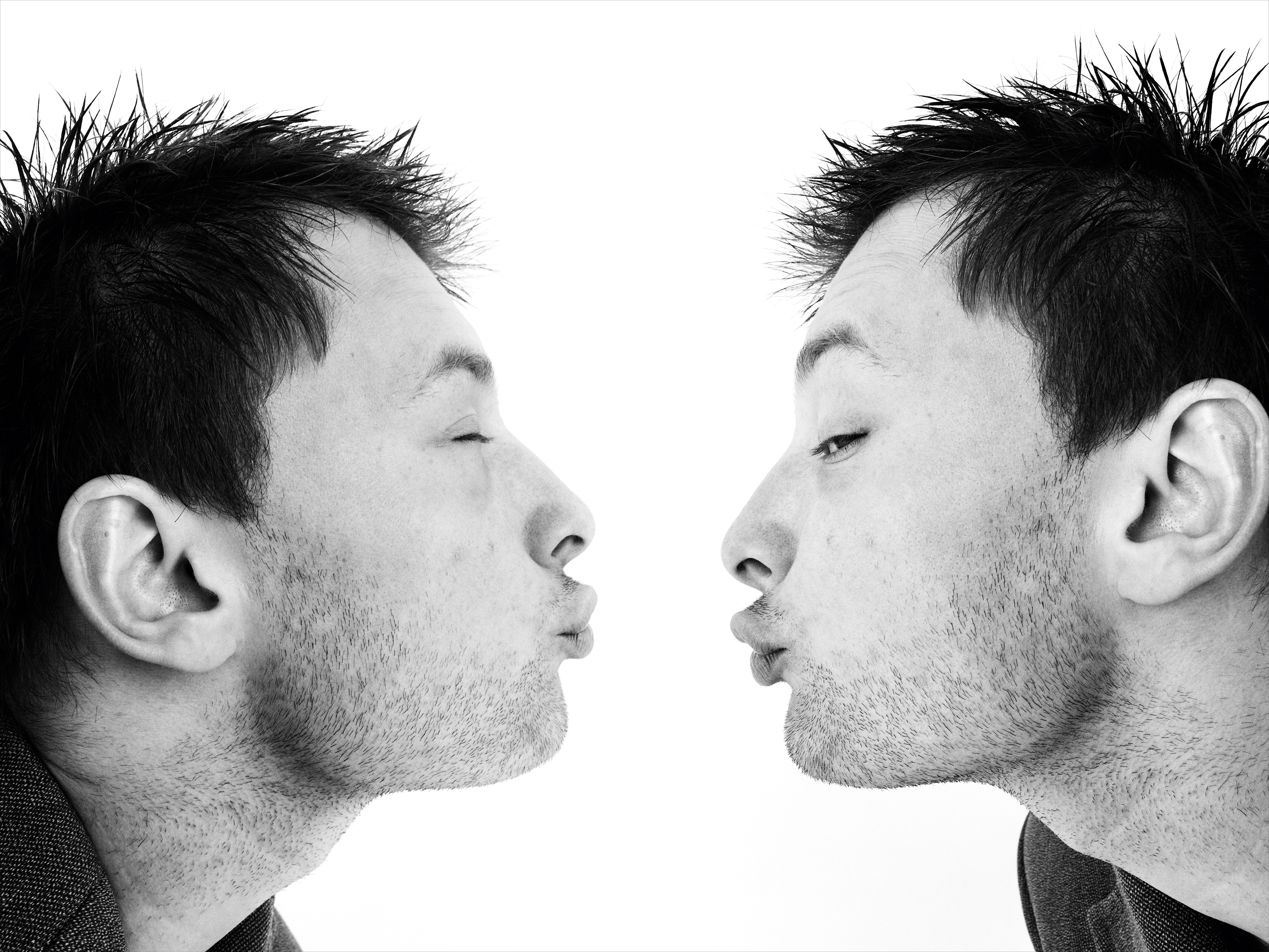

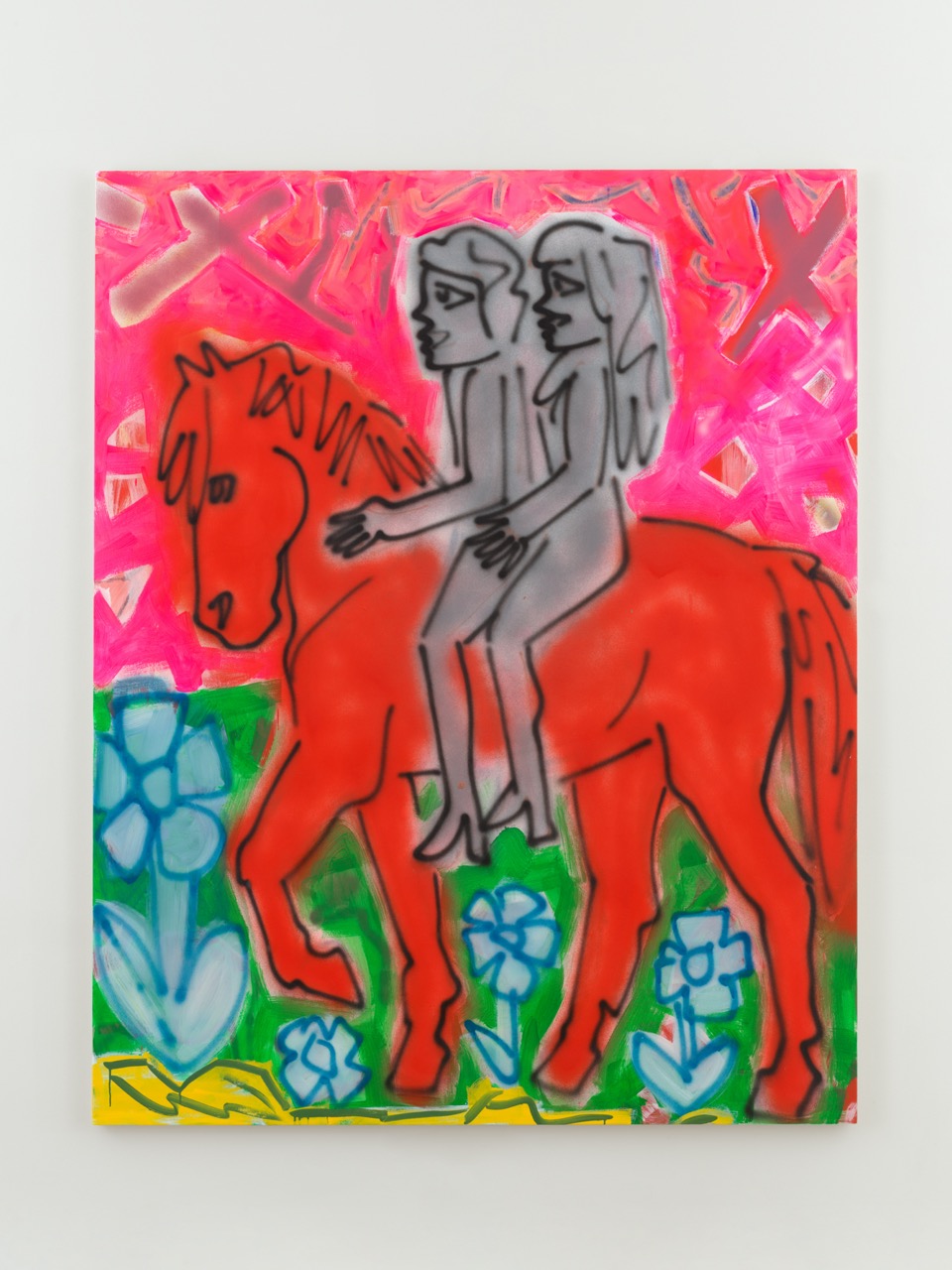

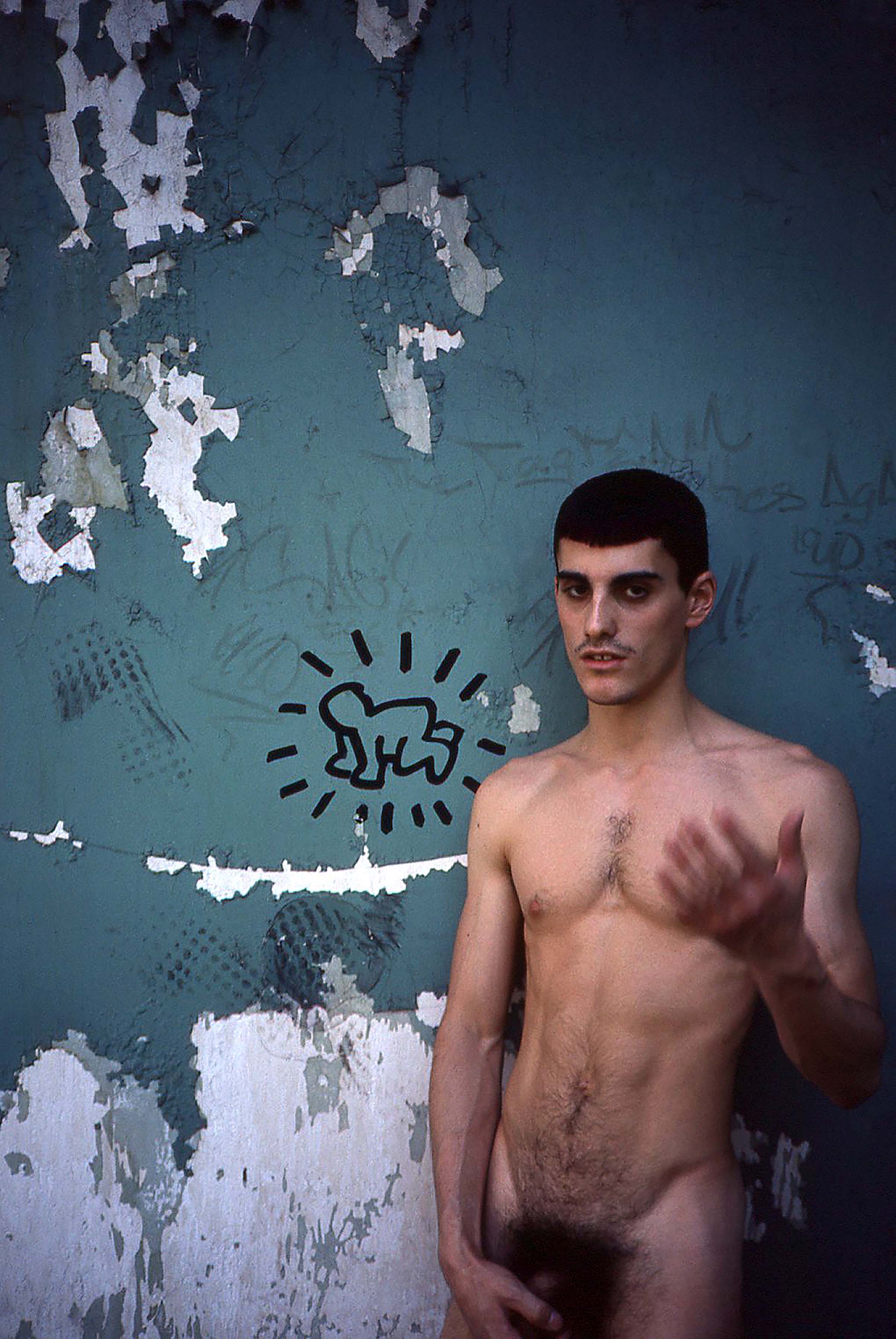

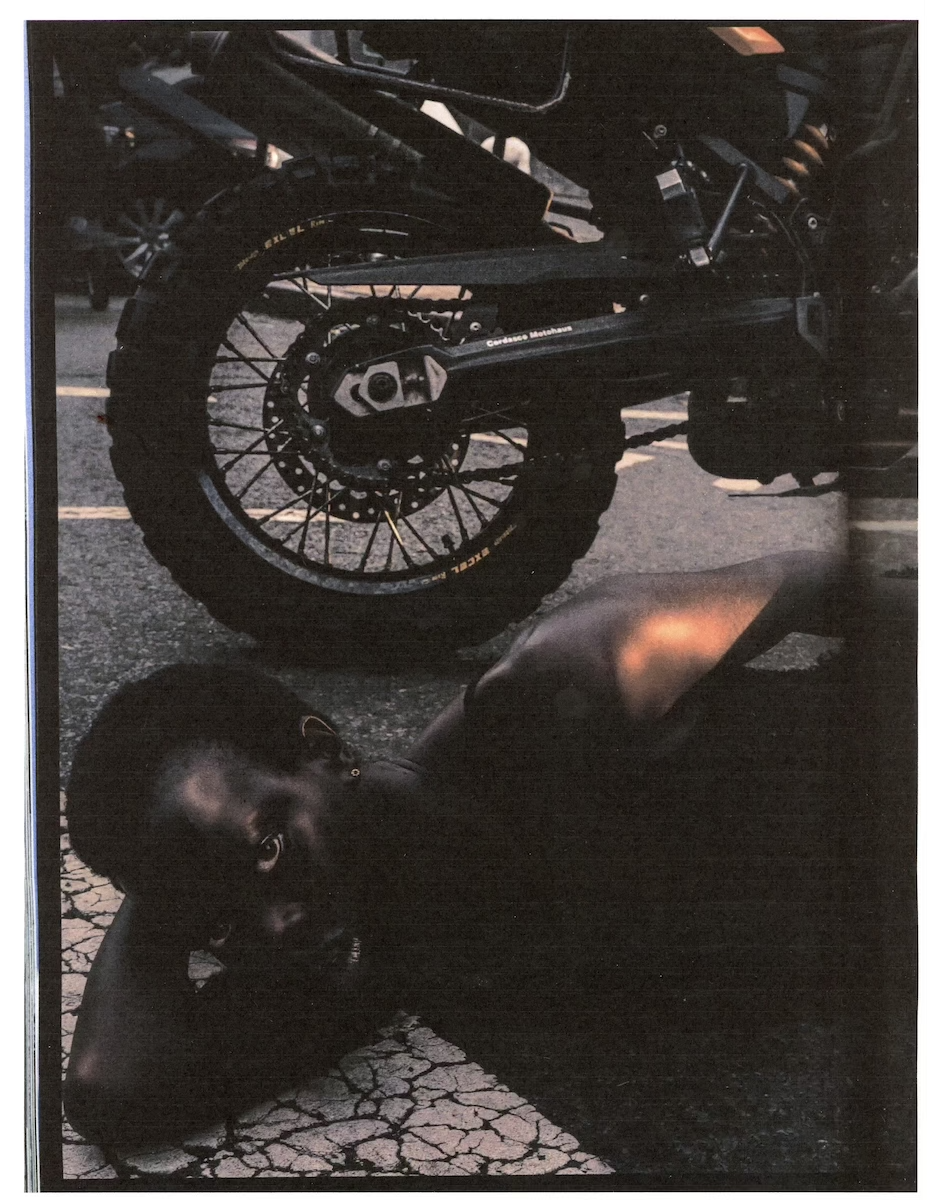

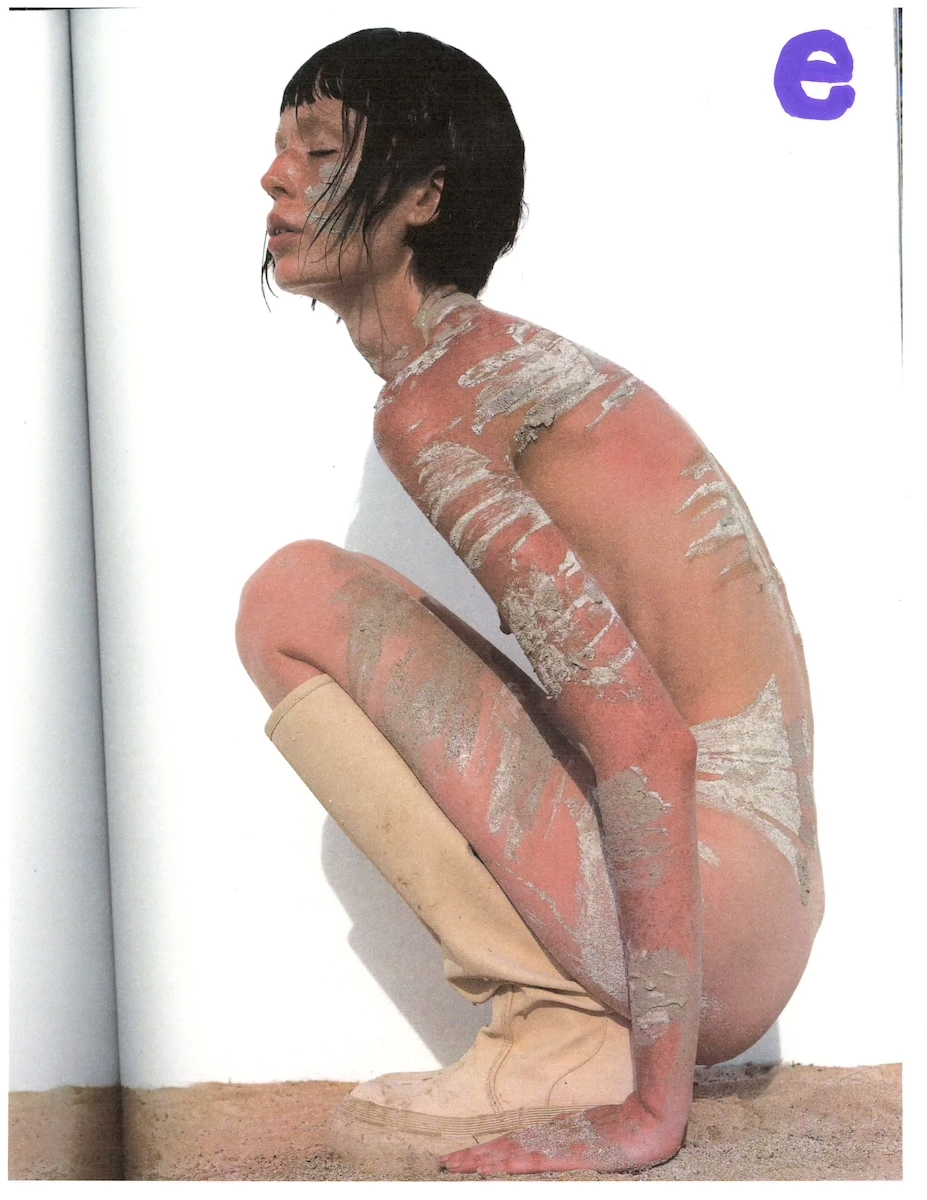

'Highly Flammable', Dazed & Confused, Issue 31, 1997 © Rankin

You can seduce it out of them. There's lots of different ways to get trust from them, but they've got to give it to you. So I try to be more honest about that. Also, photographs are subjective. They're easy to lie with. I'm trying to look for some authenticity or honesty within the lie. I'm using seductive qualities to show and reveal and give something about the person but you want people to feel good about the photograph that you've taken. I'm not trying to give them depth they don't necessarily have. It's much more direct.

Sometimes I work with young photographers assisting me. They don’t understand why I use the same skills and tools to get a reaction out of people. I see them going, “I've seen it a million times.” But, look at the results. You’re just seeing under the hood. It doesn't mean it's the wrong way.

I can't even imagine what it's like to look back on your work from 35 years ago. But if you knew how it would all unfold, what would you tell your younger self who started Dazed all those years ago?

Be nicer. I was so determined to be successful that I was a bit of a dick. Ambition got the best of me and my character was defined by that. My ex-girlfriend, the fashion editor of Dazed at the time, said I was “a show off and a bit of a dick when lots of people were around” but “on my own, I was thoughtful and considerate.” I’d also say the people you work with aren’t going away. I came from nothing really and I had no understanding of the business, the medium or the media. I was performative about being a photographer. I was pushy which wasn’t great for my reputation. I didn’t have knowledge of etiquette. I had an arrogance of naivety.

By 2005, I was like, “that's not what a photographer is.” I wanted to be a captain of a ship, not a dictator. I’d also tell myself to have more self doubt. I learned humility the hard way. It's not a bad thing to learn things the hard way because you definitely never forget them. At the same time, one of the best things about my early work is that I was a blank notebook. I developed my own taste and learned by myself. No knowledge was on my shoulders. Nobody told me this is good or bad. Everything was instinctive.