Real Slick, Jack: Psyche Organic Arrives in New York

Shop Psyche Organic at Happier Grocery and Dimes. Coming soon to @citarellagourmetmarket @unionmarket @gourmetgarage @deciccos @fairwaymarket plus many more.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Shop Psyche Organic at Happier Grocery and Dimes. Coming soon to @citarellagourmetmarket @unionmarket @gourmetgarage @deciccos @fairwaymarket plus many more.

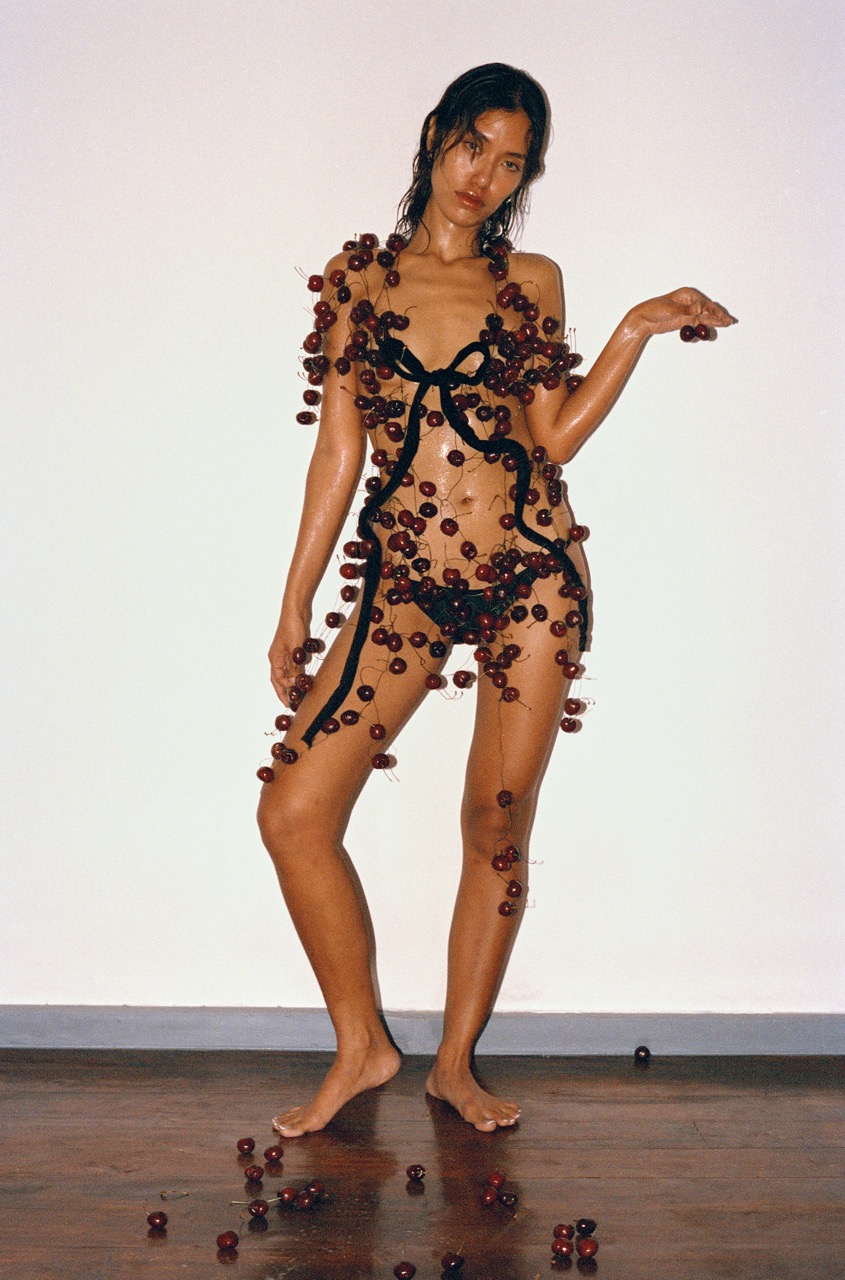

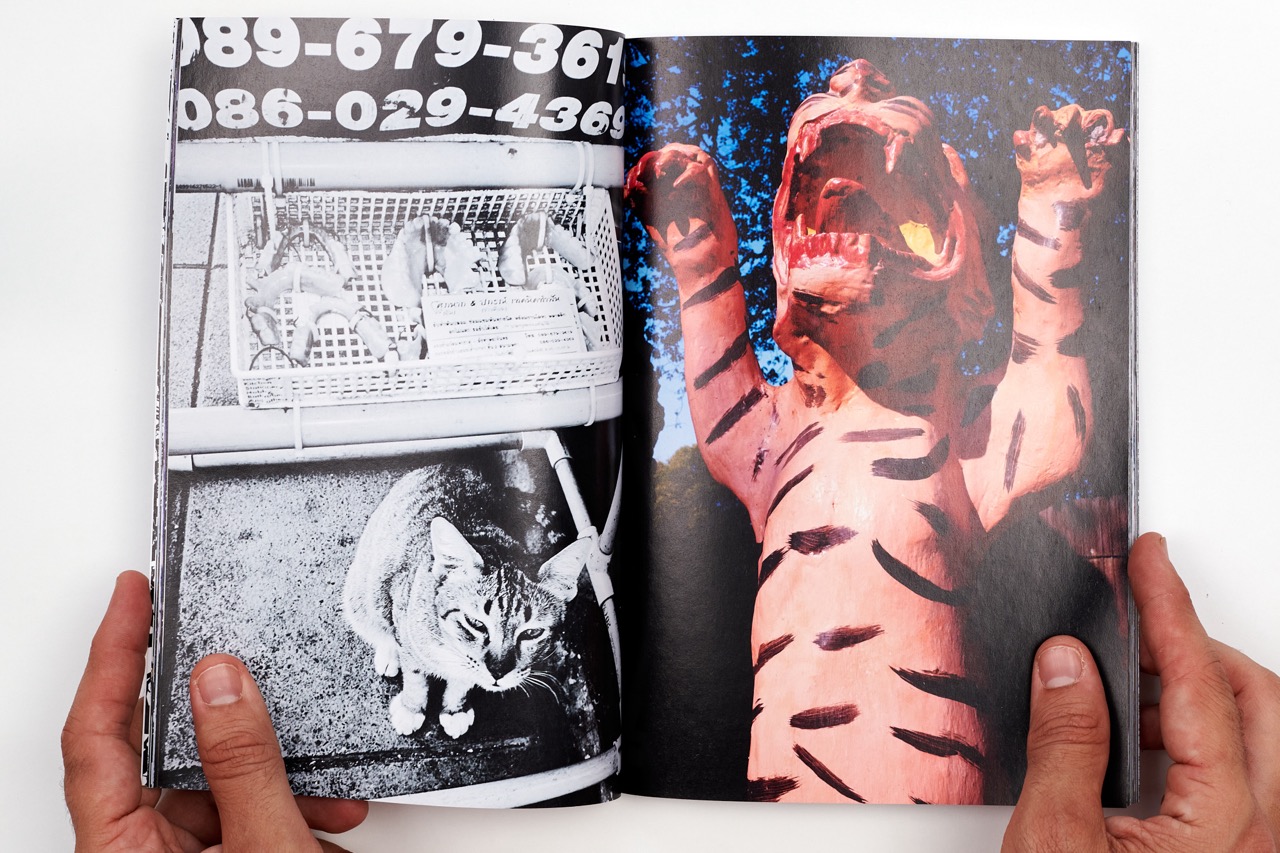

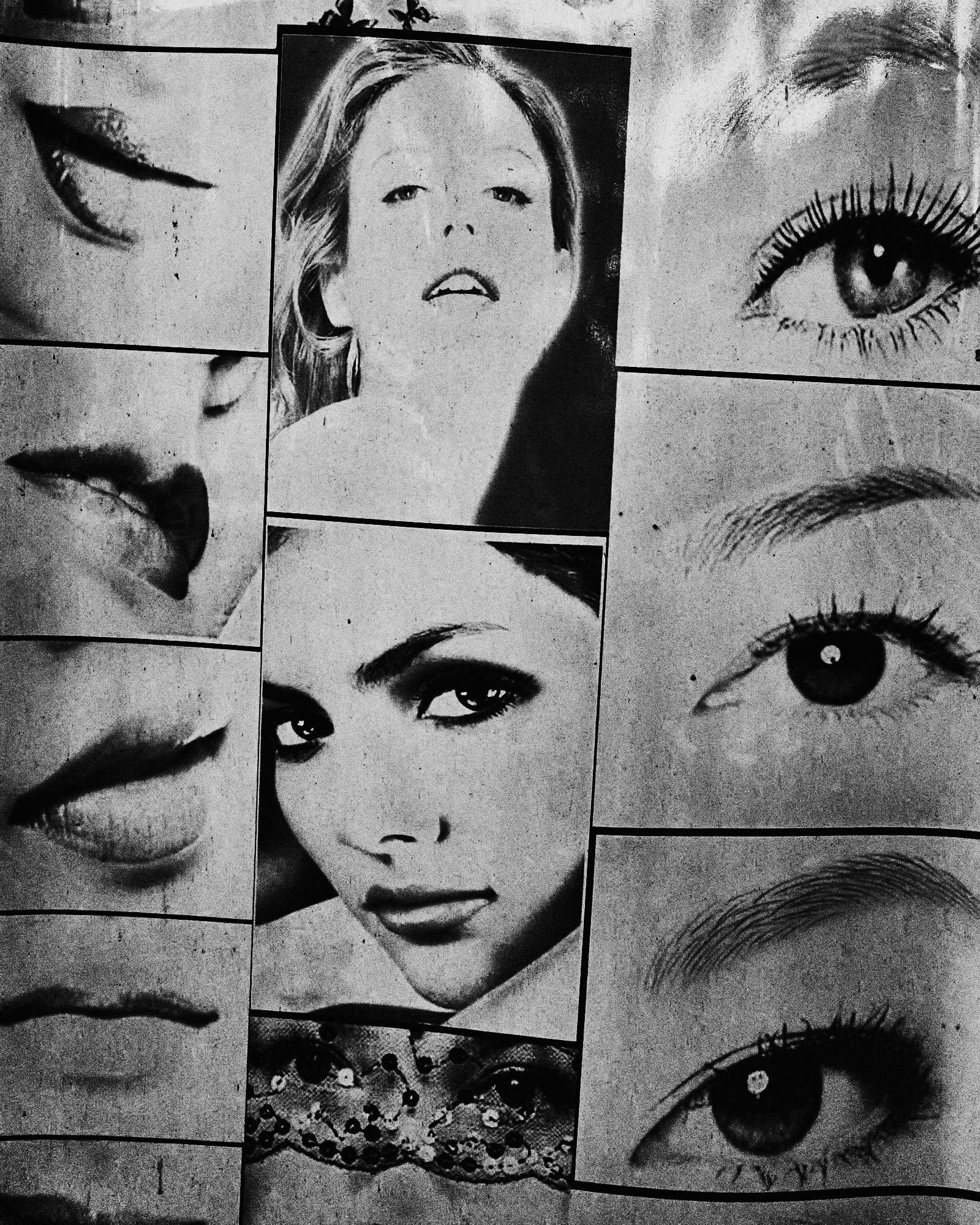

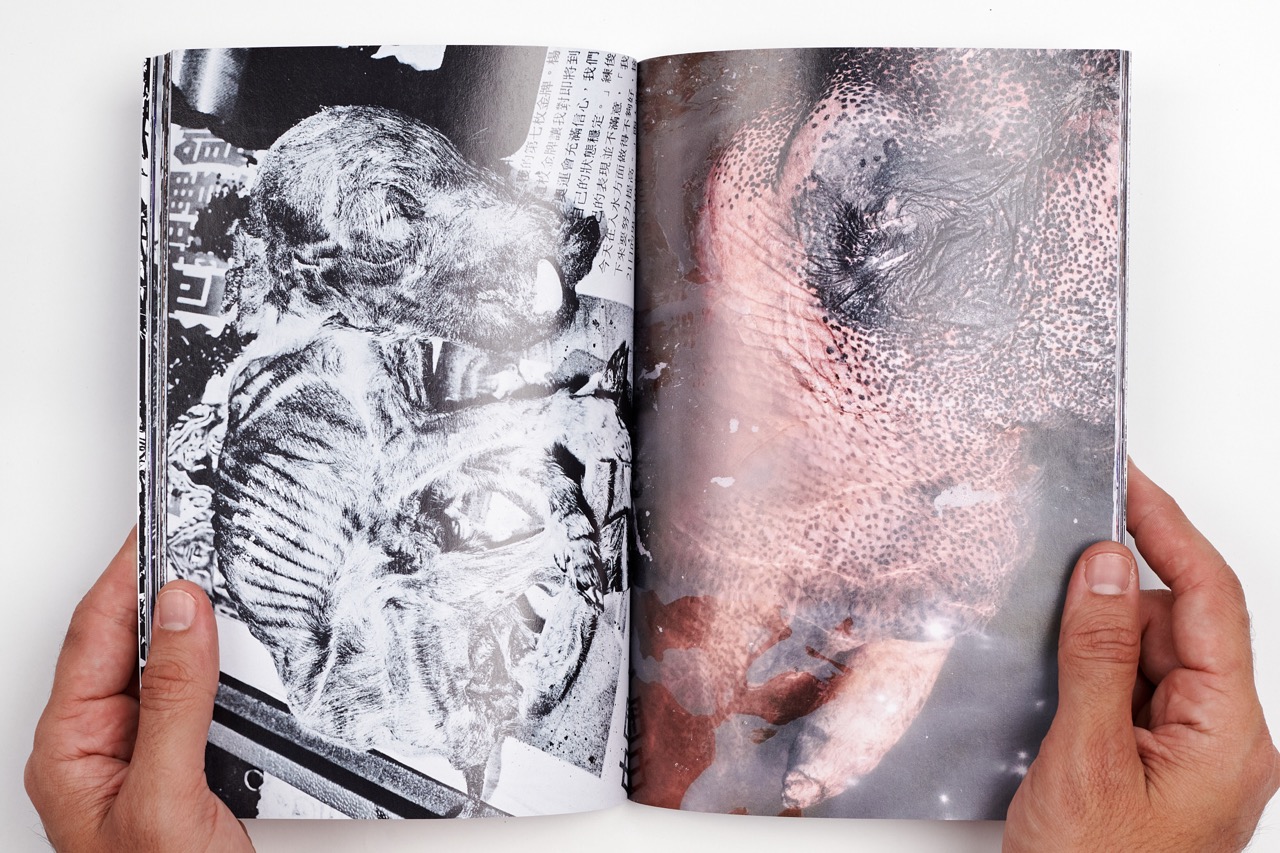

The project, published by Michael Krim’s Paper Work NYC as an 88-page book, will be celebrated with a launch event at Paper Work's flagship in LA’s Arts District on August 23rd from 6-10 p.m. To mark the occasion, 6ft x 4ft-16ft long posters featuring imagery from Banana Cries have been plastered across Los Angeles, inviting the public into the world Landis has captured. The images — a striking mix of surreal fashion and organic materials — embody the project’s themes. From a figure crowned with a headdress made entirely of bananas to a model adorned with fresh flowers and serpentine accents, each shot blends the organic and the artificial, the beautiful and the grotesque, reflecting Landis' fascination with the contrasts and contradictions that define our existence.

Banana Cries is available for purchase from Paper Work NYC here.

Qingyuan Deng— Hi Jason. Should we start with how you conceived this project, which follows your tradition of exploring a country, its landscape, and its people? This time, however, your project seems more collaborative, especially with your work alongside Eric Tobua.

Jason Landis— In my past work, I strategized concepts with well-thought-out plans and a clear vision. But with this project, I honestly stumbled into it. I met Michael Krim of Paper Work in Tokyo a couple of months before, and we immediately hit it off, spending a few days together. Michael then mentioned he was organizing a book fair in Bangkok and invited me to join him. I quickly threw my things together and headed to Bangkok with zero plan.

Banana Cries is the accumulation of what happened while I was there, with a lot of improvisation. I landed in Thailand and stumbled upon Eric’s Instagram, and immediately fell in love with his work.

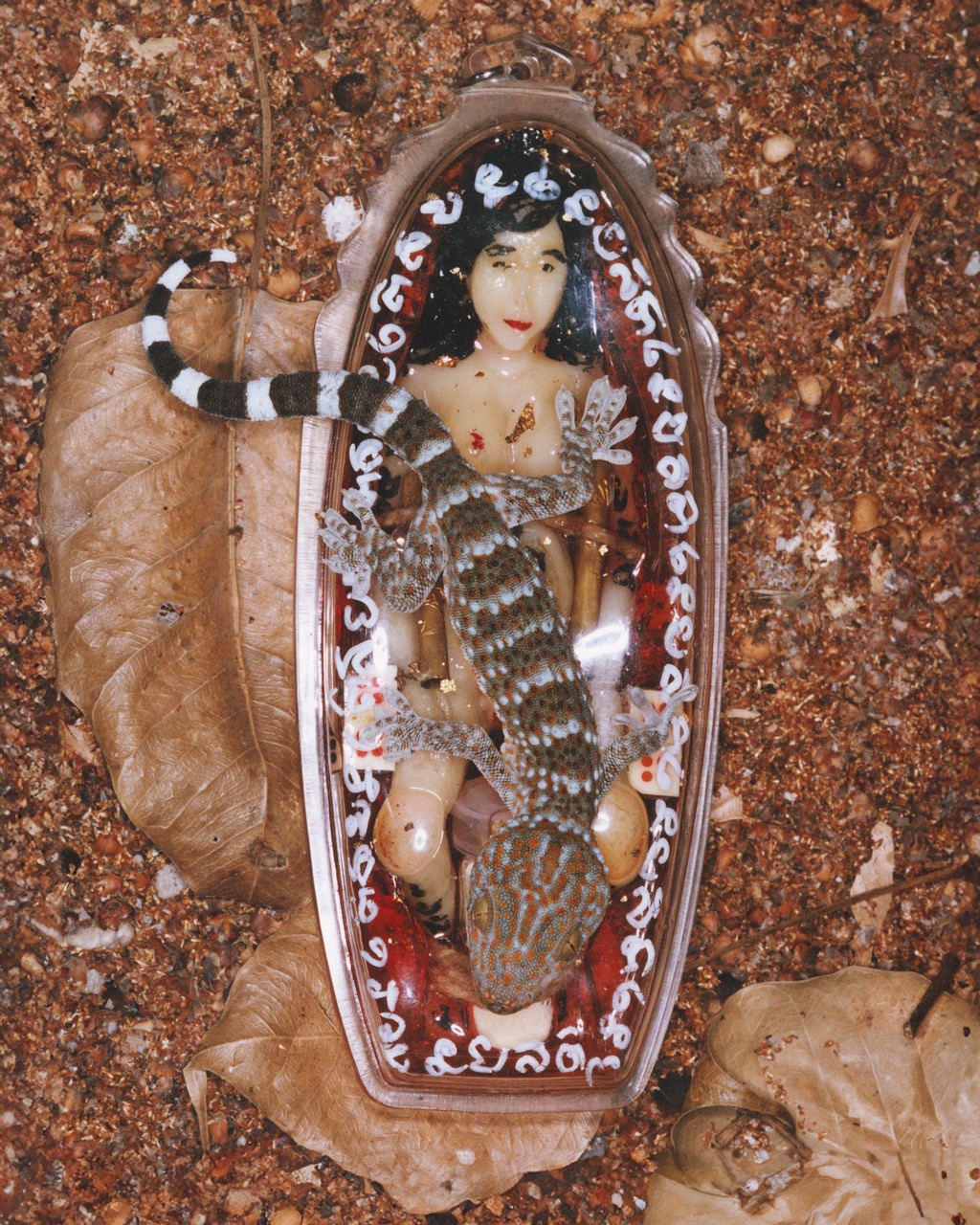

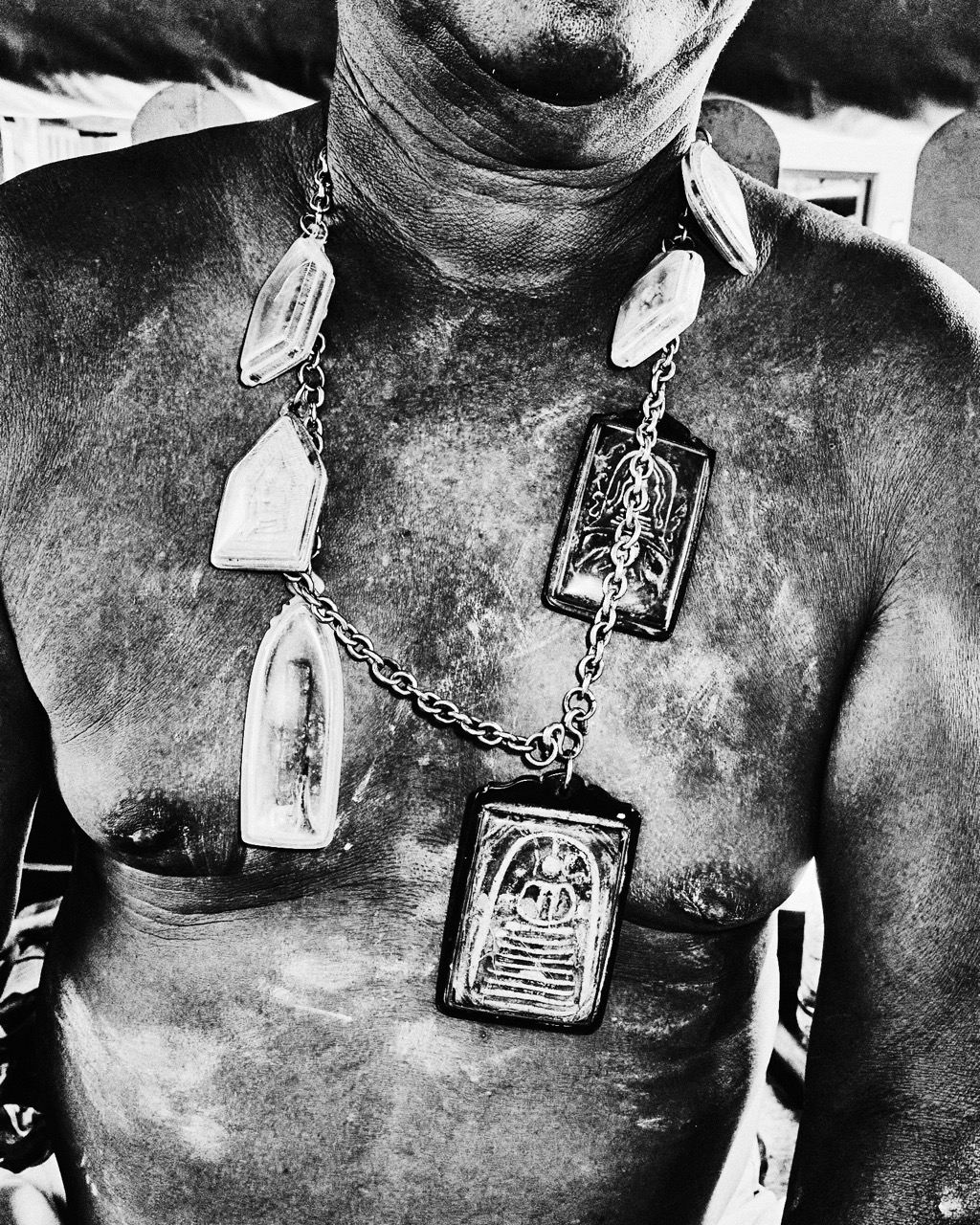

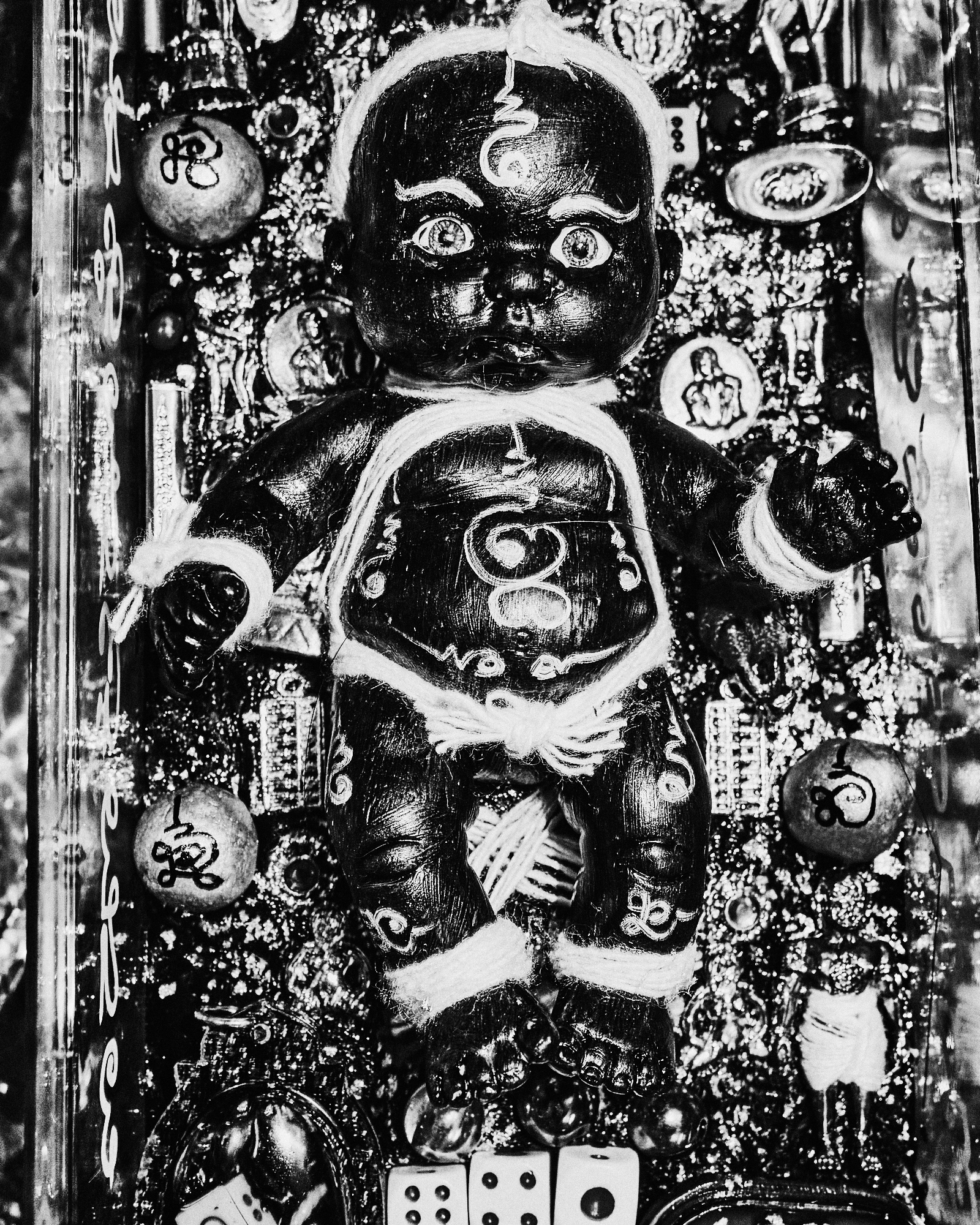

I met up with Eric at the Standard Hotel just after visiting the forensic museum and the amulet market. The forensic museum is like a beta version of the Bodies exhibit. You enter a random building in the hospital with a sign pointing to the forensic museum one way and body donation the other. They have the police report, the murder weapon, the tattoo skin used to identify the perpetrator, and the remains of the victim. At the market, I bought various amulets, filled with different oils and ingredients, blessed by an Ajarn. Some were for protection, others for good luck, fertility, and prosperity. I’m hoping to explore more of that the next time I’m in Thailand. I showed Eric some of the photos I sneaked from the museum and the amulets I purchased. Three days later, he showed up at my friend’s coffee shop with two cars full of fruits and animals (one of which was his pet giant snail). He made the outfits on the spot, molding them to the models’ bodies.

Beyond working with Eric, I also went on some side missions after getting in touch with some “herpers.” Herping is like playing real-life Pokémon. They took me to a sewer behind a train station just outside the city center, which was a hotspot for venomous snakes, drug transactions, and hookups. We met a lot of interesting characters there — people who were curious about the snakes because they knew others who had been bitten while hooking up. My herping friends were advising them on which snakes to avoid and what to tell the hospital if they got bitten.

It seems like you really became an intimate part of the community there, learning about things that aren’t visible or accessible to everyday tourists.

Yes, the zine is both a reflection of my time in Thailand and a self-portrait through the lens of Bangkok. It’s almost as if I created my own world inside Bangkok through these chance encounters.

Some of the most identifiable themes in Banana Cries are desire, sexuality, death, and decay, which seem like a continuation of your past interests.

Absolutely. In Bangkok, the same street vendor could be selling the nicest mangoes you’ve ever had, and a few hours later, they’re selling Viagra and sex toys. You could be at the forensic museum looking at a mummified body, and in the next building over, someone is being born. Banana Cries explores the bond between sexuality and mortality. It seems like these themes aren’t as taboo in Bangkok—sex and death are just part of life. Everything is right in front of you, nothing is really hidden. That’s how I feel about this project, which sets out to find connections between polarizing yet intertwined elements.

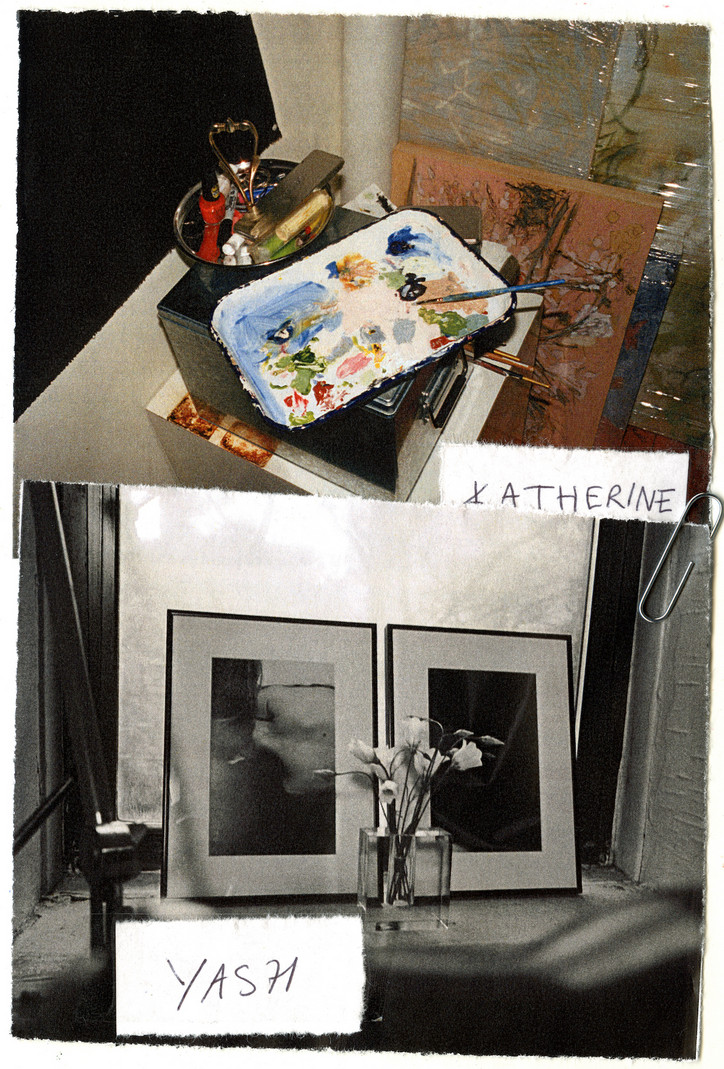

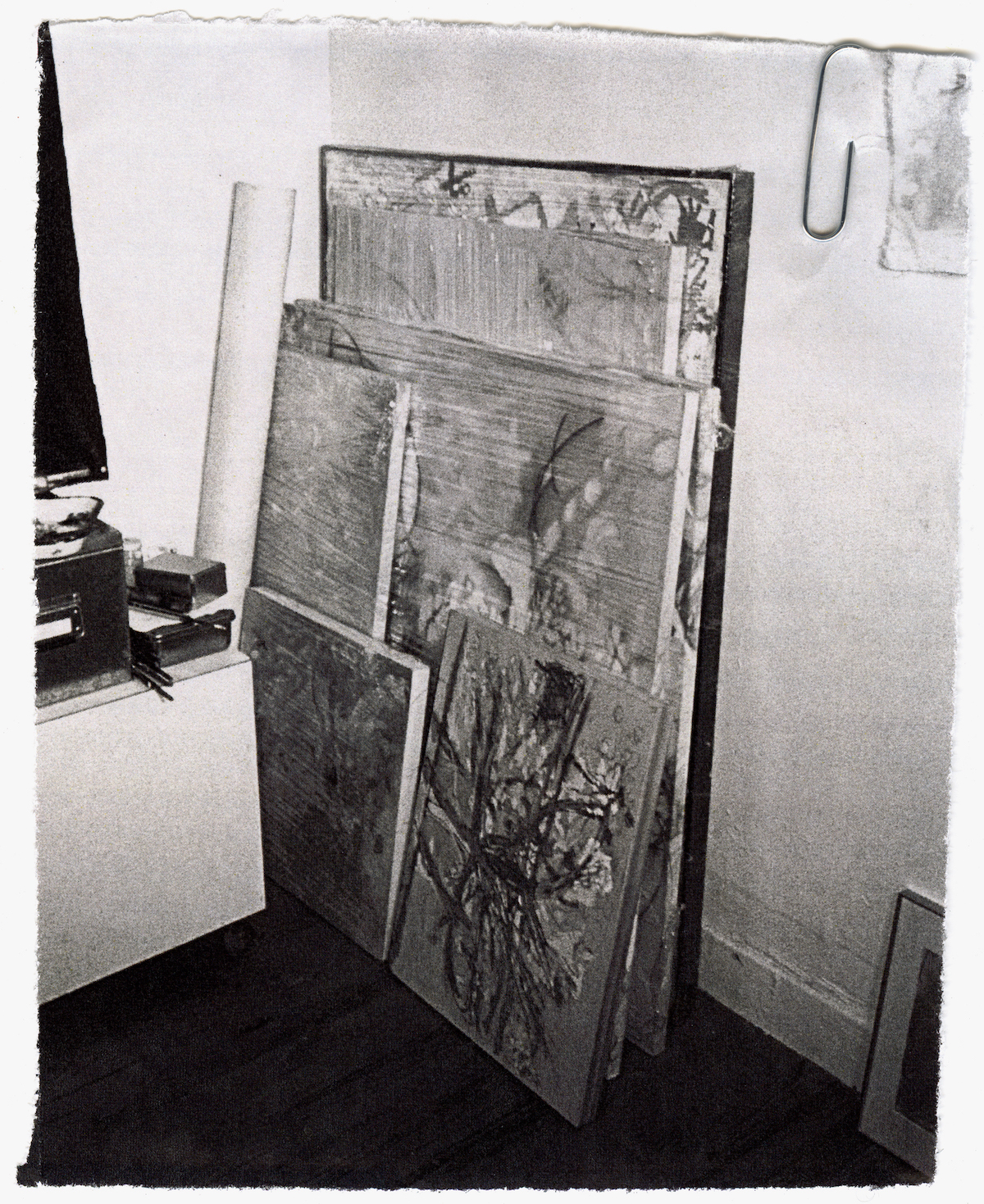

If female artists are discussed at all, they are discussed in terms of tragedy. Few are celebrated in their lifetime, and even fewer get a say in the legacy of their art. The Swedish painter and pioneer of abstraction Hilma af Klint, whose work is buried beneath the mess on their coffee table, is one example among many. But Auchterlonie and Yahshel refuse to be sidelined, selectively selling their work to buyers who they know will be able to properly preserve their work. Auchterlonie started the summer by exhibiting at the legendary Brooke Alexander Gallery on Wooster Street, whereas Yahshel began hers by turning down requests from European art fairs.

Below we speak of fake puppies, chain-smoking, love languages, sloppy kisses, desire, and of course, Hilma af Klint.

Katherine, you just moved in with Yahshel. I’m curious about what’s left behind in the old apartment.

Katherine Auchterlonie— I’m 95% here, missing the champagne glasses and some fake puppies.

Fake puppies?

KA— They’re replicas of dogs in old paintings. “Old paintings” as in the 18th century when portraits peaked amongst the privileged and their painters developed a visual language to communicate “underneath the various forms of wealth.” The artists themselves seem cool but the subjects were often uncool people. Anyhow, a sleeping dog became a symbol of infidelity. For example, you’d see a portrait of a couple on their wedding day, both very clean, very dressed up, very happy, whatever; perhaps they would have the father painted in the background, and two dogs on a leash. If one of the dogs were asleep, it signaled that the groom was cheating.

That's brilliant.

I wanted to make something out of it but it hasn’t been my vibe lately. I’m not that bizarre right now.

No sleeping dogs in this apartment. Who does the cooking, who does the cleaning?

Yahshel— I’m the chef. Kathrene leans heavier on the cleaning side if we’re being diplomatic.

KA— I wake up to the smell of her cooking.

It’s not even the sound, but the smell. She keeps quiet so as not to wake you up before the meal is done. That’s love.

KA— Cleaning is my love language.

Me sexting.

KA— But at the same time, I can’t have it too clean. I need an organized mess, especially a girly organized mess; some champagne bottle wires lying around, some old deli receipts, and… maybe a cracked eyeshadow? That’s when I’m inspired. That’s when I’m like “Okay, I know who I am today, let's get to work.” It’s an identity thing.

I was waiting for you to drop cigarette butts, too. Cooking and cleaning in all glory, but who does the cig-runs?

Y— We always pick up double packs at once.

How many cigarettes does it take to finish a painting?

KA— Oh my god. Let’s just say I’m glad my piece on Wooster [Street] is behind glass.

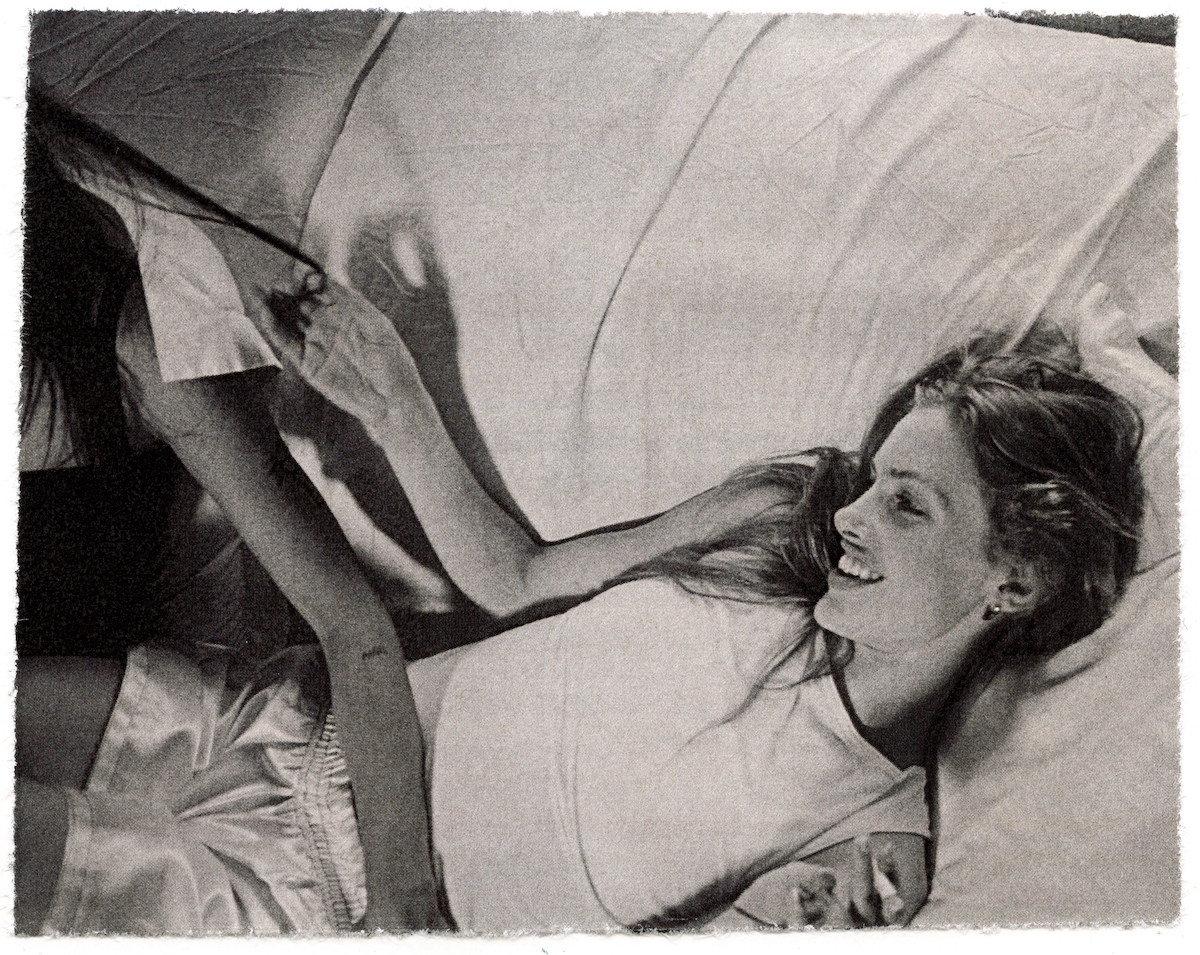

Through some of Yahshel’s photographs of you, it’s almost as if one could smell the smoke. I mean that in the most sensitive way. In your duo show at The Sitting Room [gallery], the works were displayed not only in conversation with each other but the symbiosis felt as if the works completed the other’s sentences. How much does your practice overlap?

Y— There isn’t a way that I could think of them as either dependent or separate.

KA— I mean our art is our approach to life. And Yash is a big, if not the biggest, part of mine. She influences how I feel, and how I feel naturally bleeds into what I make. It’s inevitable, maybe in the best way possible, because it allows the work to go outside and beyond myself.

All my research for my upcoming show, dating back to last April, has been centered around a notation system for diagram kissing; kissing in a way that’s not creepy or gross. The motif, however, is completely without people. I’m fundamentally against pictorial representation — it just never interested me. I almost see figurative as Islamic and why would I as an artist care about representing what God already made redundant? My practice is more abstract; I would even propose this diagram exploration as a scientific notation, which scratches an itch for me. The ultimate goal is to create an open-ended code that anybody can read and, through it, visualize an entirety of that kissing experience of their own.

In Notation of a Good Make-Out Session — your piece for Unrequited — I visualize you and Yahshel dancing around while making out, and the X’s are either where her tongue touches yours or vice versa, or perhaps that's where the heart skips a beat? Or maybe that’s me being the creep you set out to cancel.

KA— No that’s hot.

The inspiration for that piece came from the “Feuillet-Beauchamp” notation — a dance sheet commissioned by Louis XIV. The dancers read these un-abstract abstracts and followed a choreographed dance based on the drawing. Once I stumbled upon it (via internet tourism) I was like, “Okay, this is it.” So now I’m charting love in a notation system; some movements are hot, elsewhere, the kiss could read as really sloppy.

Have the two of you ever had a sloppy kiss?

Y— Do you want us to show you?

Correct me if I’m wrong but this is where the artisanal overlap takes place, in the exploration of love?

Y— Sure. I guess we started exploring the subject artistically through some [love] poems we once sent one another, which later were used both as titles and the press release for the Sitting Room. Kate’s approach to the subject matter is somewhat biological…

I mean, there’s Hilma af Klint on the table.

KA— I’d love to be compared to her. No doubt biology was my favorite class, much more inspiring than (male!) art history.

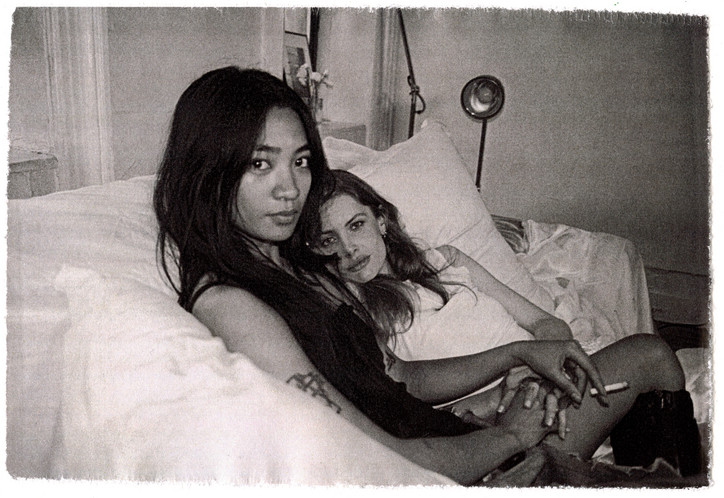

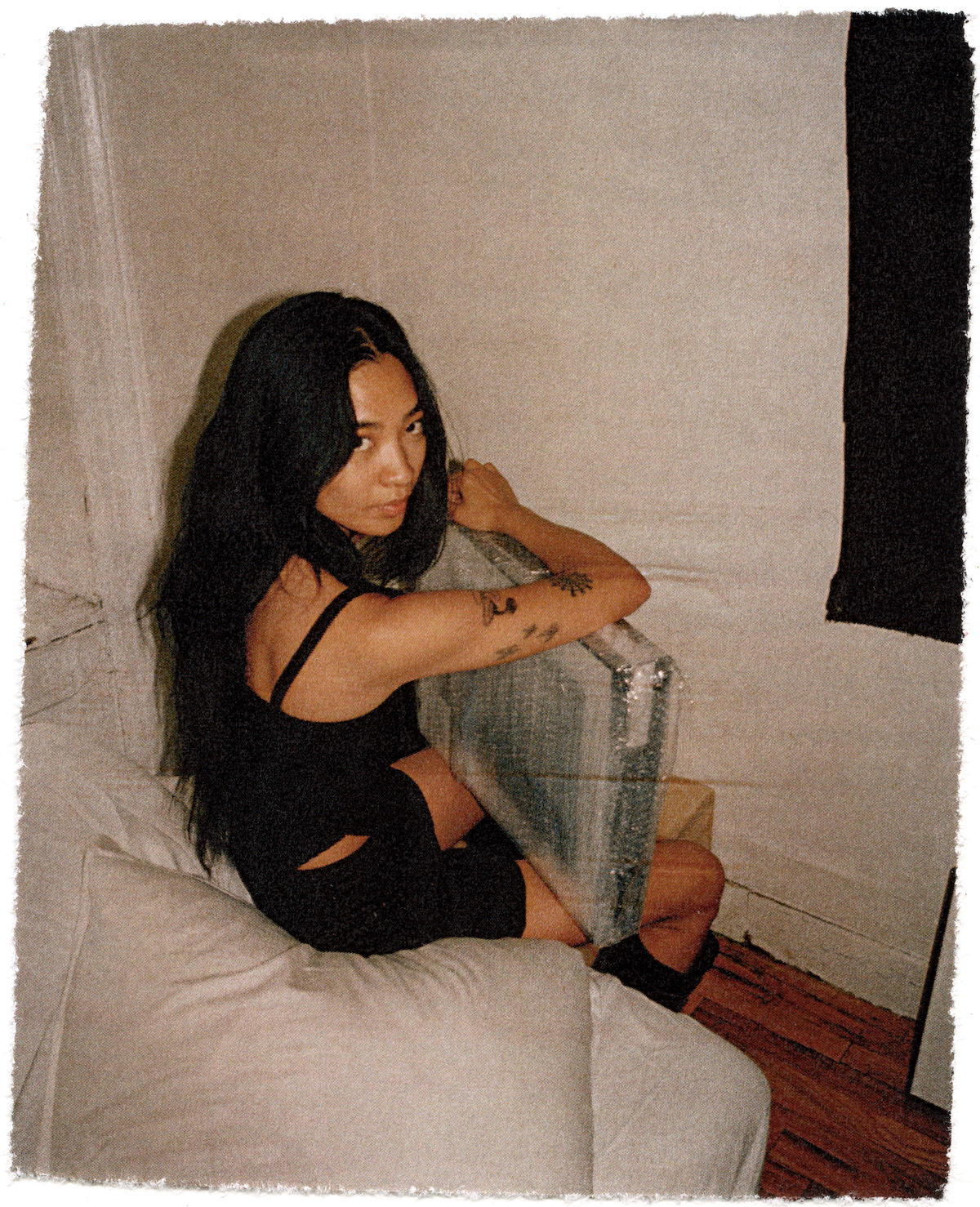

Y— Whereas my practice is exclusively photography, abstracted photography nowadays.

“Nowadays” dating back to when?

Y— I played with abstract for the last show mainly because of Katherine and how much I was exposed to her work. Before that, the majority of my photographs were straightforward portraits: friends having fun, fucking around, like any other “photographer” around here. Why I consciously didn’t tap into photography earlier wasn’t because I wasn’t curious, but being raised in the Philippines the idea of a profession has always been reserved for academics or sports. Art was never on the agenda. It took me moving to the States to realize that people are artists.

Until recently, I’ve always been “taking photos,” but Kate would roll her eyes and say, “No babe, you are a photographer.”

Your practice sits above the usual artist-muse relationship, thereby resisting falling into that objectifying false worship, and it’s brave, maybe even scary to expose something as intimate as one’s own love.

KA— The scariest part about being an artist, and a human being, regardless of what you’re portraying, is that you’re constantly hoping to be understood. Therefore, your work is somewhat contingent upon you being alive. Imagine growing up and realizing that the artists understood in their lifetime are men, whereas female artists are only later, after their passing, acknowledged as “underrated.” It scares the shit out of me. After consuming X and Y amounts of books, art history classes, and going through common art gallery conversations, was when I realized. The way people talk about women artists is tragic; they were never shown, let alone had a proper say about their art while they still were breathing. Or at the very least over 80 [years old].

Referencing af Klimt again, she’s such an accurate example.

KA— Exactly. She wasn’t an abstract artist, but google her name, go to any retrospective at any big institution, and all the labels, and websites, and auctions, will tell you exactly what she was repeatedly rebelling against. It proves that women were never appreciated for what they spoke of, but for what society was comfortable with. It doesn't help to make the work more direct. Nor do I want to. However, perhaps it inspires me to make my work physically bigger. It’s freeing to have a whole wall to paint on, almost like a cave painting. But it’s also a flex to be a small person and paint large formats. I guess that’s me saying that my dick must be bigger than yours.

What does it mean then to be self-taught?

KA— To have originality. It’s not about anything more or less than that. If you’re learning because secretly in your heart you want to look like something, or somebody else, then great, you’re a copyist and perhaps you should pursue that. You will make a shit ton of money. But then don’t come and claim this boho lifestyle. Your identity is not a painter. Saying it out loud now makes me realize how I believe it’s about intention, too. And intentions are harder to undress these days.

I’ve painted since the age of four. When the people around me started asking what I’d like to do once I get older, my response was always to be a painter. I’ve always had an answer, yet people kept asking me. Eventually, I realized that their asking was their way of saying no — if they had accepted my answer and my passion for painting, the question would have moved on a long time ago.

Y— It’s almost the same as when we run into people, and they keep asking if we’re still together. Why wouldn’t we be? We’ve also been told that it’s severely stupid of us to date each other because we could do so much better financially. It’s hidden in their phrasing, the tone of their voice, “But you’re such a pretty girl, you could be with someone who could provide you with…”

I believe that if you’ve truly ever experienced love, you would never question another person’s way of loving.

Y— Regarding your question on the scarcity of intimacy, I see the responses toward our art and relationship as validation for our work. Not because everybody votes for it but because they’re suspicious about it. It adds a dimension of social responsibility. It addresses that today, people are terrified of being vulnerable, even amongst their friends, and sometimes even around their loved ones. It’s as if we’re all set out to use the same script once we move through these interactions, and if we don’t we’re doomed. Love will always look different, but the kind of language that I hear is so damn uniform.

KA— You’ve got to have a communist mentality. My feminist theory professor would always say, that regardless if you have to make your change go beyond the span of a lifetime, eventually, your voice will be heard.

Y— That’s why archival works are so fucking important.

Making art is different from the drive to preserve your work, how do you create from that desire?

KA— It’s all the same to me. You have the drive to preserve your work because you truly believe that it is that important — because it needs to stay after you’re gone and, you know, you can’t take it with you when you die. Once you realize its value, you start aiming for galleries and private collections, then museums, because at the end of the day, you need people with air conditioning to buy your work, because that's how it stays in good shape.

Suddenly you’re no longer making art for your mother’s walls; she’s out of space, the house out of empty rooms, and eventually she will be gone. Eventually so will I. And I can’t archive my own work because death is real.

Only for humans. Original art is immortal.

Katherine Auchtomom’s Kiss Garden will be on view at Ross + Kramer Gallery until August 16th, 2024.

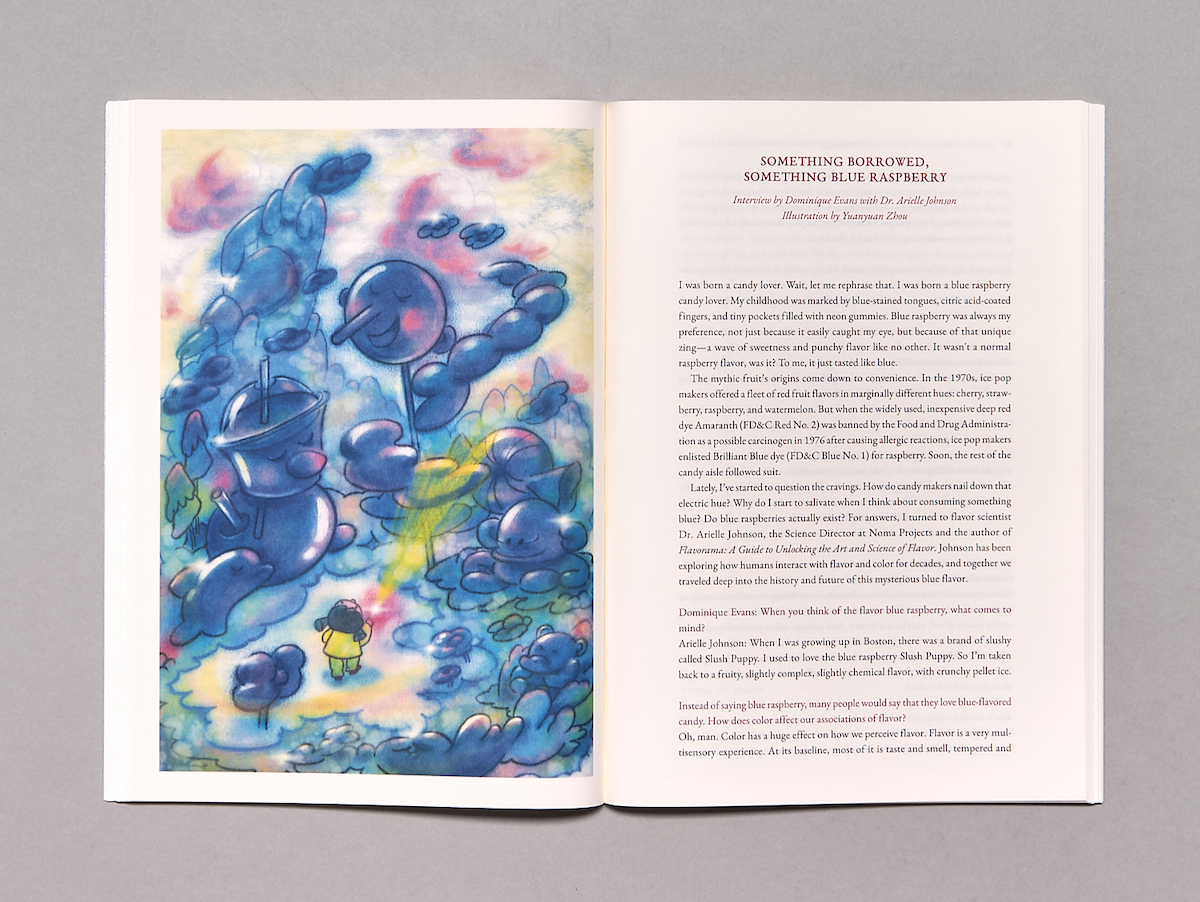

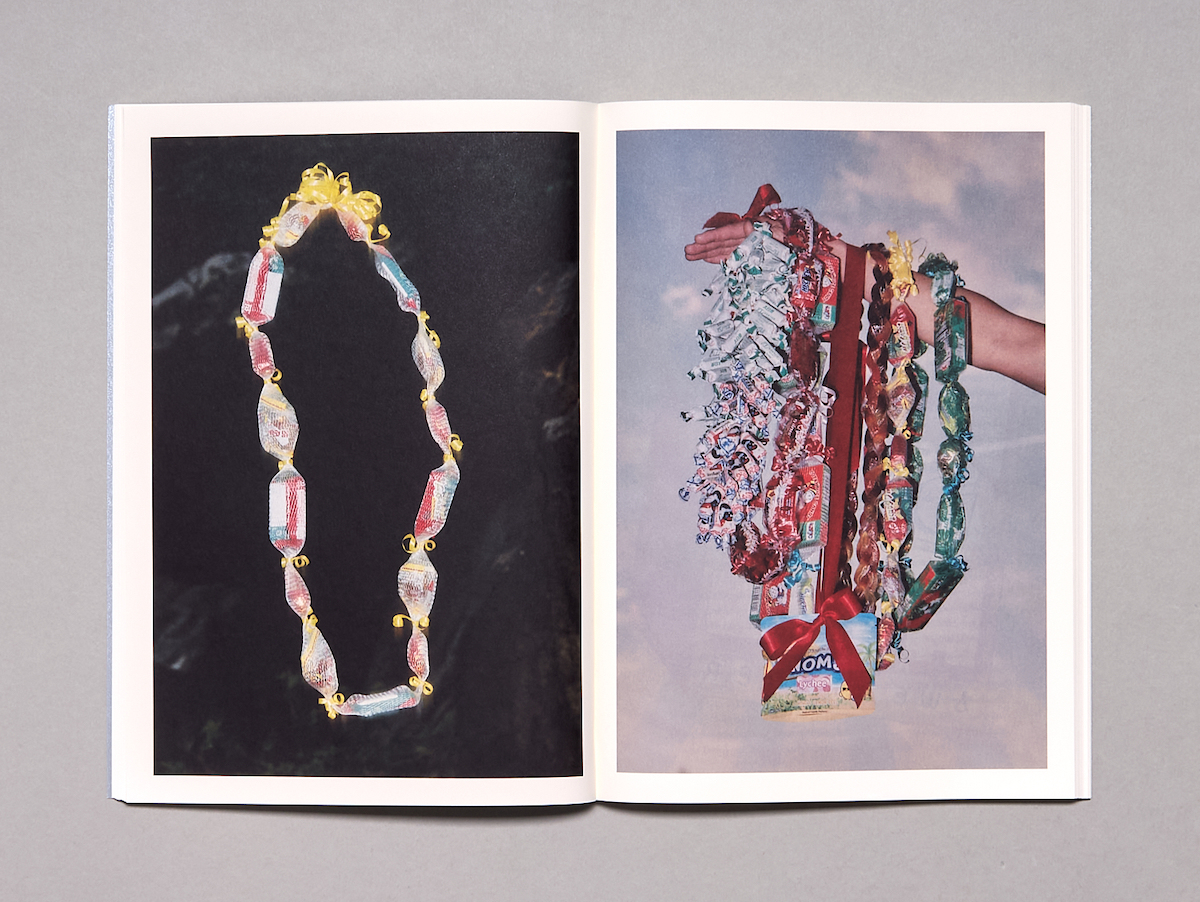

The launch party for this issue was no different from previous ones: a feast for the senses, especially taste, with botanical cotton candy spun onto flowers and Del Maguey-spiked mezcal jelly cakes. A few days earlier, I spoke with Tanya and Aliza about this new issue and the associations that it explores: candy as pleasure, childhood nostalgia, connection to distant cultures, as well as its roots in labor, gluttony, colonial extraction, and exploitation. With a diverse range of contributors unraveling these connections, Candy Land directs critical attention to familiar confections and flavors, highlighting their deeply person and historically global significance in their highly-processed and preserved glory.

Sofia D'Amico— Having just finished the Candy Land issue, I came away with the feeling that I’d read contributions from such a mix of people from different backgrounds— science, history, art, food industry, activism —and, of course, they’re each tackling the topic of candy from different angles. I am speaking from an arts background, but it’s a curatorial decision for these publications that you've put together such varied contributors. I’m curious how you pull together the community for each issue?

Aliza Abarbanel— The curatorial part of the process is the most core to what we do, and we are lucky to have a very robust community of people answering our pitch calls. At the end of every year we sit down and think about our themes for the year ahead. We had a really hard time deciding our summer issue and wanted to do ice cream, but we couldn't think about the right lens for the theme, because we don't just pick a food item, we want a specific context in which we're exploring and then refracting it in as many ways as possible. So with Candy Land, I played that board game all the time as a kid, and started thinking about how candy feels like it's so far removed from the land, but everything we eat is, at its core, tied to these organic ingredients. Candy has impacted the way we allocate and use land in different ways. So we set the pitch call in that framework, and get maybe 300 to 400 pitches per issue just for written content, not including illustration, and we also solicit from people. And as you've read, we probably have about 20 slots in an issue. Then a big part of what Tanya and I do with our editorial board is discussing how we can include as many different perspectives as possible.

Tanya Bush— Yeah, I think that's core to the Cake Zine ethos, that we are an interdisciplinary magazine. We are using these very narrow lenses to explore culture, art, history, and food. That's sort of what Candy Land allows us to access; it’s an interesting subversion of themes. So we have the piece “Candy Land: A Revisionist History” by Elaine Mao on the actual board game Candy Land, but then we have a piece by Simon Wu on kandi with a K, EDM, raver culture, and PLUR. And I think that because we have such a narrow theme, it allows for writers, artists, cooks, and people of all different backgrounds to hone in on something really specific. We have our first piece of fan fiction in the issue, which was really exciting and strange. For every new magazine that we do, we want to incorporate unexpected forms: taxonomies, fables, and listicles. We did a comic once. That was fun.

SD— Yeah, this made it such a rollercoaster to go through. With this issue, some of the features were really funny and joyful or more didactic or historical, and others had really dark undertones. It is a nod to the endless associations that people have with candy itself, in that in some ways it’s a marker of nostalgia, and in others, it's about gluttony or excess. Do you think about that balance when you're putting together an issue?

TB— We don't want to publish a magazine that's an onslaught of darkness, so we are very much thinking of an issue holistically… We want there to be a dynamic balance of hard-hitting reporting and more optimistic features with levity, as one needs in a magazine about dessert. We are first and foremost a magazine about dessert.

AA— With our issue Wicked Cake, the whole theme was talking about this dark side of a food like cake. I think famously of Matilda and Bruce Bogtrotter as a Wicked Cake thing that people would think about. But in general, cake is often super frivolous and fun. And for Candy Land, again, candy is so joyful. But more than any dessert we've covered so far, it's so linked to mass commodification, mass farming, and consumption. Most people don't make candy at home. We all know the history of the sugar trade in this country around the world, how it's linked to slavery and globalization and colonialism. A lot of these big corporations and their labor practices are impossible to ignore, so when tackling this theme, that was something that naturally came up. Part of doing a kaleidoscopic look at a theme would have to, of course, touch on that. But then we want the M&M fan fiction moment in there. We want someone who's diabetic talking about how sugar-free candy is campy and fun in the same moment, because those are obviously core to the candy experience in contemporary culture, too.

SD— And for both of you coming from the kind of food landscape, did you feel like there was a gap in a lot of publications and scenes that specifically connects food discourse with cultural production of different disciplines more widely?

AA— I think there are a lot of food publications that we really admire. I think MOLD and LinYee Yuan’s work is so incredible, and they do a lot of interdisciplinary and forward-thinking food work. Really, we did not intend to start what Cake Zine has become. We just wanted to make a magazine with our friends, then, very thankfully, we had a really great response to that issue and the party we did around it. That heartened us to keep going. Speaking for myself, leaving Conde Nast, I did want to make something that I could never justify to an international corporation business office as being a worthwhile pursuit.

TB— And we are a print only publication, which I think is worth reiterating. We are not constrained by covering hyper-timely stories. As Aliza is saying, we literally cannot because we print in the UK, so it takes a few months to get books over, and if we're going to try and publish something super topical, it's already going to out of vogue by the time that it comes out. So I think that is really liberating and exciting because it means that we're not sort of beholden to the traditional constraints that a larger media publication needs to be. Because we have this sort of niche audience, people really resonate with the more historical literary approach that we take.

SD— It's nice that you have this emphasis on your events too, because food culture is so much about community. And there's also this idea that the issue itself can act as or can deliver little pockets of pleasure. One of the topics that a lot of the contributors are nodding to is that there is this need for greater pleasure and nostalgia in a really challenging and difficult world. Do you guys have any personal reflections on that as you were thinking about the issue?

AA— I would say nostalgia is one of the biggest flavors. In all desserts, in every issue, we encounter people who want to talk about things from their childhood, family members, and recipes. It's interesting because it's such a personal feeling. I recently found out Tanya has never played the game Candyland, so I need to bring a board and we can play it, but it's not a good game as after reading the issue. It was created for children in the polio ward, so it's possible to lose. It means that as an adult especially, there are no stakes to it, but as someone who grew up playing it, I look at those characters and I remember being a kid and thinking they're so weird. They've been around for such a long time, and it's just kind of fun to consider the game in a new way. But, I would imagine for someone who's never played Candyland, reading that article was still interesting.

TB— Yeah, it's an iconic game that is such a part of the popular imagination, so even if I didn't play it, it loomed large. I used to have an extraordinarily fierce sweet tooth, but now that I'm a baker and I have to taste glazes and curds at six in the morning, the last thing I'm going to do is lunge for a Snickers bar. But, this issue has very much reinvigorated, maybe reawakened my appetite for the pleasures of candy at the right moment. I used to be someone who would store all my Halloween candy under my bed and savor it over the course of many months, and it was such a pleasure.

AA— Yeah, especially being a kid with candy, this concept of scarcity. When is your Halloween stash going to run out? Did your sibling eat the last brownie before you? And Paolo's piece is also about dumpster diving for chocolate and the dumpsters getting locked up in the Pacific Northwest and becomes more influenced by tech. This issue itself is almost taking a look at our moment of abundance, sweetness and how much candy is left in the jar.

SD— The issue also does a lot of that work too. In thinking about conglomerates, the implication of Chiquita is important. Also, even just on purely a level of underpaid labor. The piece that was on the Hershey's at the theme park and growing up in that neighborhood too, was this really interesting and kind of dark implication of this space, thinking about labor, especially in those contexts, the international student labor uprising was so crazy to read.

AA— Yeah. And we knew we wanted a story in our pitch guide. We called out Hershey, Pennsylvania and in general company towns because we just thought if we're doing a story about land, it would be interesting to hear from somebody who grew up in a place that was literally built for candy, but we didn't expect to receive this pitch from Maya that talked about her experiences working there and the experiences of other people working for Hershey, which I think that's why making magazines is so great is that we can have an idea for something and then it can end up being so much more.

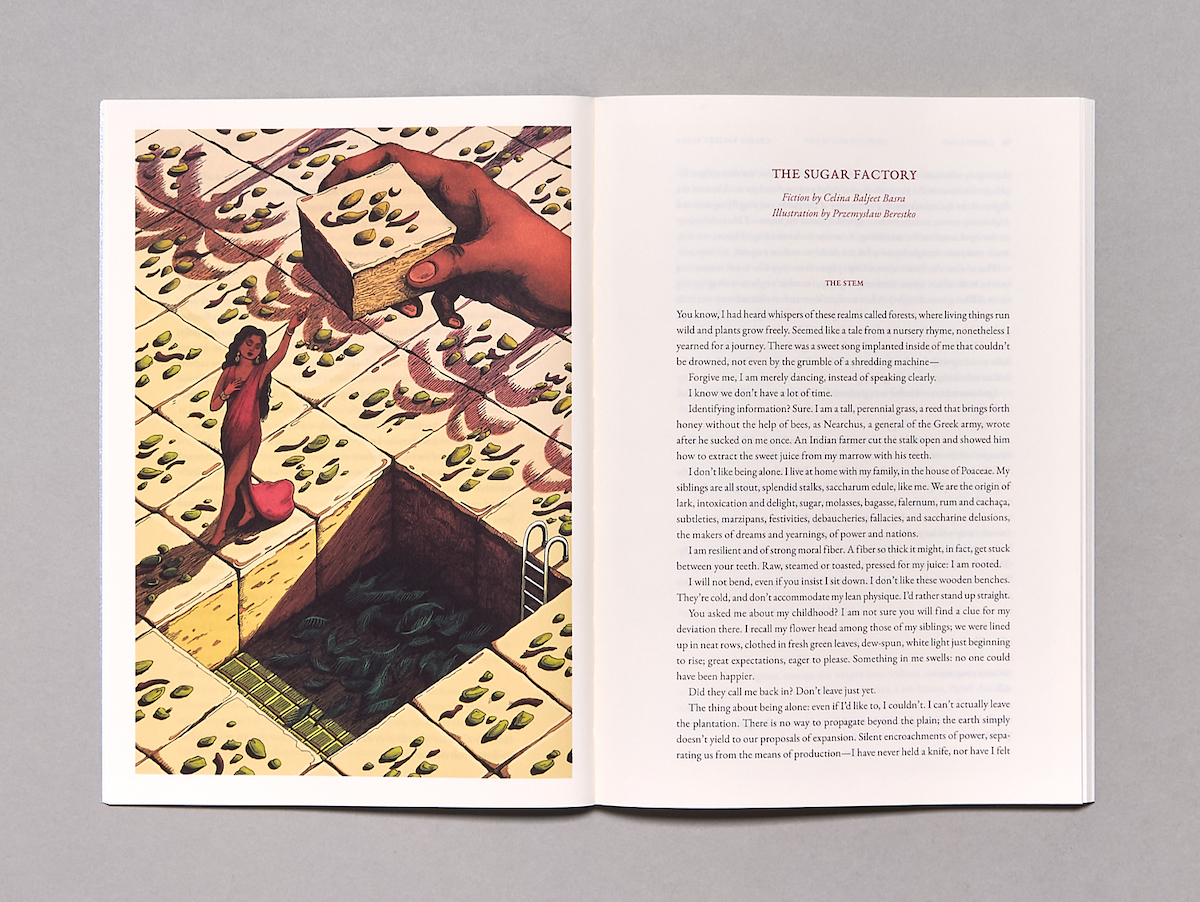

TB— I feel like now that we're talking about it, it makes me think of “My Father's Tongue” section in Celina’s piece, “The Sugar Factory,” which is sort of tracing the lifecycle of a stock of sugarcane to this mass produced sweet and the labor that's sort of involved in that. And I think it's cool that we have both this reported personal essay about a labor awakening and contending with the company town that you come from, and then also having that rendered in a sort of more whimsical literary mode where you're not necessarily being told exactly what's happening, but you can sort of intuit based on the factory calendars that the father is sending home and his early hours. You get the perspective from a variety of different junctures in the magazine.

SD— Yeah, the variety in the delivery and the different modes of writing are really effective. And then there are pieces that channel people's connections to an immigrant narrative or connection to a distant culture or family, too. So there's this interesting dual-narrative around labor as well as immigration, or thinking about diaspora and cross-cultural experiences.

AA— There's whole subreddits where people trade candy from around the world, or when you go on vacation and you bring candy back with you, it's one of those souvenirs that is so easily transportable and does offer really cool insight into what are the tastes of a certain place. That reminds me so much of some of the things that Gabrielle talks about in the banana candy piece about how she had a passion fruit skittle before she ever had passion fruit before. The way that things from other cultures and places can travel easier sometimes when it's in a candy form.

SD— In the research for this issue, this is kind of a silly question, but were you eating a lot of candy or in preparation?

AA— Certainly in preparation for this party, we have been spending a lot of time thinking about candy. There will be a lot.

TB— I’ve been incorporated into baking, but have just started testing something with Whoppers as part of the base crust. I love the taste of malt, so I feel like the issue has very much opened up the way that I think about candy in my daily life now and in my baking life.

SD— Oh, sure. Zoe Denenberg’s dirt n’ worms tiramisu recipe in the issue is so smart. I think it's such a cool reinvention of something that's so simple and quotidian, they were such a cheap treat, and this is such an interesting take on something and really making it contemporary.

TB— I love that recipe. Just to tease the party, Libby Willis is filling a literal six gallon fish tank with dirt and worms and we're going to probably have shovels on site and get people to sort of dig for their dessert.

Which brings me back to scooping chocolate pudding, oreo crumbs, and gummy worms onto my plastic plate. The genre-bending concepts at play in Cake Zine are well-demonstrated by the Candy Land issue, which posits candy as on the one hand a nutritional, ecological, and moral warning signal—like a neon dart frog. But on the other hand, candy is connection: to culture, to land, to one another and ourselves.