Real Slick, Jack: Psyche Organic Arrives in New York

Shop Psyche Organic at Happier Grocery and Dimes. Coming soon to @citarellagourmetmarket @unionmarket @gourmetgarage @deciccos @fairwaymarket plus many more.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Shop Psyche Organic at Happier Grocery and Dimes. Coming soon to @citarellagourmetmarket @unionmarket @gourmetgarage @deciccos @fairwaymarket plus many more.

Jupiter was born out of the conversations that Bacon and Harper had at that very first dinner, though neither of them knew it at the time. They commiserated about their jobs and the constraints that had been placed on their writing; “breakneck timelines” from editors that discouraged formal experimentation had drained their work of its pleasure and hindered its potential. They bonded over their shared childhood dreams of one day working as magazine editors. A few days afterwards, the conversation hadn’t left either of their minds. So the two women decided to write a manifesto, figuring that other writers must be encountering similar tensions in their practices.

“Something that we say often, that might sound hyperbolic but I think is really true, is that writers are an endangered species. Writers are going extinct in this very, very distinct way,” Bacon says. “I use that language because I think to speak of extinction is also to speak of a broader ecosystem that is deficient, that does not hold the things that we need it to in order to really do our work.” They continued developing their manifesto, meeting over Zoom after Bacon returned home to Chicago, and decided to add a micro-grant component to help support writers. By the next time Bacon visited New York and met with Harper in person in April 2023, the bigger picture had clarified: they were creating a magazine.

“It was like the sun broke through the clouds and streamed into the coffee shop. Our meeting allowed us to realize that we needed to create the publication that we wish we could have written for, become the editors in chief that we wish we could have been supported by,” Bacon describes, referencing Toni Morrison. “It's really fueled by this shared philosophy around the importance of writing, of course, but also the conditions that we need to deeply enjoy it. Can we create ecstatic editorial conditions? is the thesis we’ve charted forth on.”

Bacon and Harper share a steadfast belief in the importance of art writing and the art critic at their best as belonging to the ecosystem of creation; in other words, part and parcel of the art itself, not separate from it. A good piece of art writing can facilitate an audience’s connection with a work, and excavate further meaning from it, even for the artist themselves. “The art of criticism itself is rooted in care, and can be viewed as an act of care and can be really practiced as a tool and a method towards deepening and lengthening not just our lines of inquiry, but also ultimately the ways that we understand ourselves and each other better,” Harper says. “I've been really astounded to learn the different ways that I can discover more about myself, about my loved ones and the people around me through really deep and spiritually led excavation around art, around art making processes.”

“But when we think about the way that the world is currently set up right now — care cannot be a cliche. It has to be a mandate,” Bacon adds. “And I think having this willingness to really grapple with art objects that challenge me conceptually, aesthetically, emotionally, spiritually is a way of answering to that mandate of care at the moment.” That process requires time, and providing writers with that time is one of Jupiter’s core intentions; Bacon and Harper know that in order to live alongside a work or art object for long enough, writers need proper compensation and more generous deadlines.

The magazine’s name came to them later down the line, after they had already first announced their joint venture at a panel event in Chicago. Bacon says she began waking up at night with “dispatches,” unable to return to sleep until she had written down the messages that popped up in her head. One night, the dispatch simply read jupiter. After some reflection, she and Harper fell in love with it as an “incantation,” one that promised a long prosperous life. Jupiter is the planet of expansion, abundance, and luck; it is also a gaseous liquid planet; it also rules over both Harper and Bacon’s astrological charts.

“It’s the one truest expression for what it is that we've been working towards building, which is ultimately something that has this air of malleability; it's elastic, it can stretch, it can bend, it's not pinned down in any one particular way,” Harper says. “And both of us are really deeply led by spirit, and allowing that to shine through with such clarity and vigor is something that's really important to us — within the art space, but also in general within editorial spaces or what might be considered a ‘professional space,’ these spaces ask us to silo off parts of ourselves in their corner. I think Jupiter felt like the perfect way to really assert who we are and be really loud about it.”

“Art criticism is seen as this extremely pretentious, extremely erudite, extremely curtained off discipline, and we're interested in bringing a degree of unruliness and waywardness into what that means. Criticism is happening all the time, we're just not calling it that,” Bacon adds. “And I think naming the publication after a planet rather than something that feels more legibly intellectual is really important to signal the way that we are also trying to bring a shift in who regards themselves as a critic and who reads criticism."

Read the inaugural digital issue of Jupiter Magazine here, featuring contributions by Akwaeke Emezi, J Wortham, Rianna Jade-Parker, Joshua Segun-Lean, and Diallo Simon-Ponte.

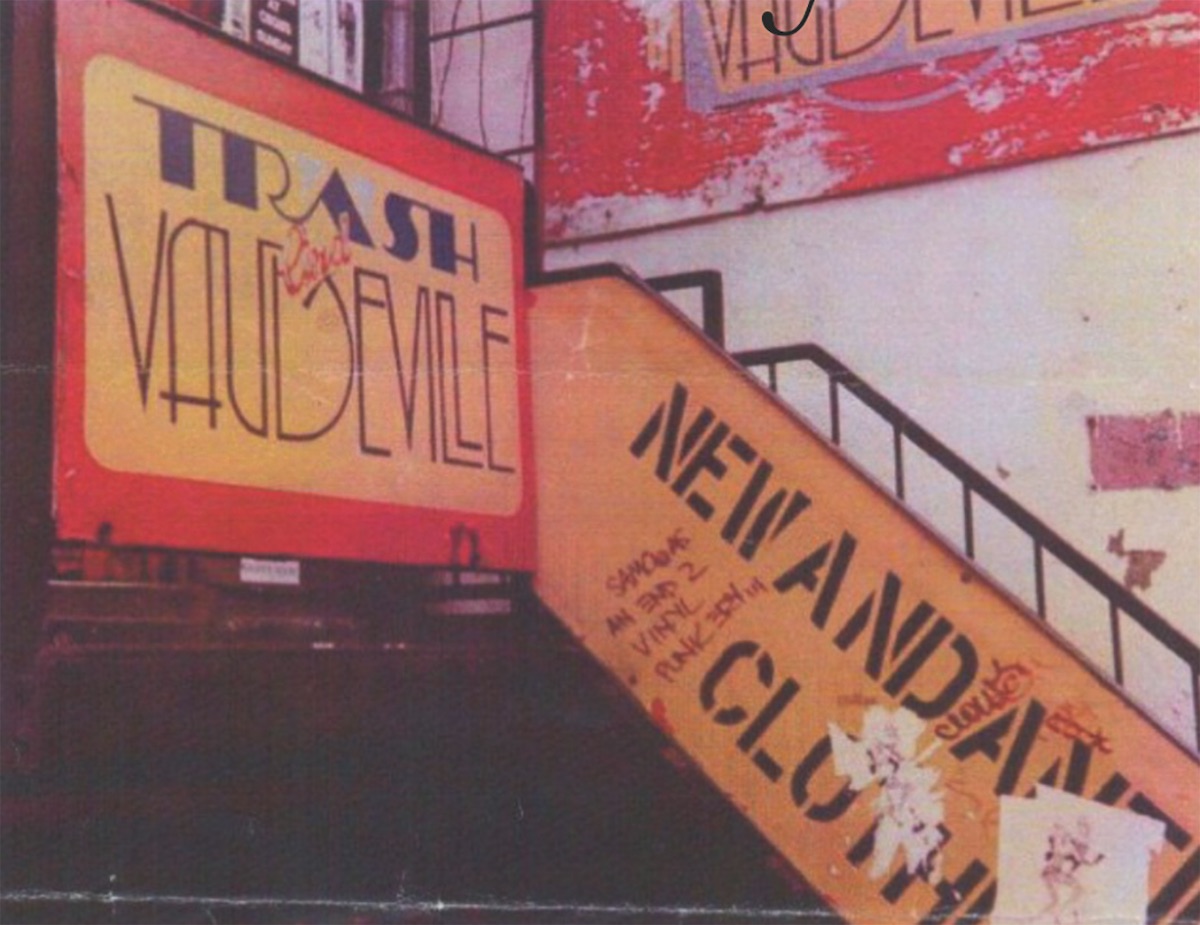

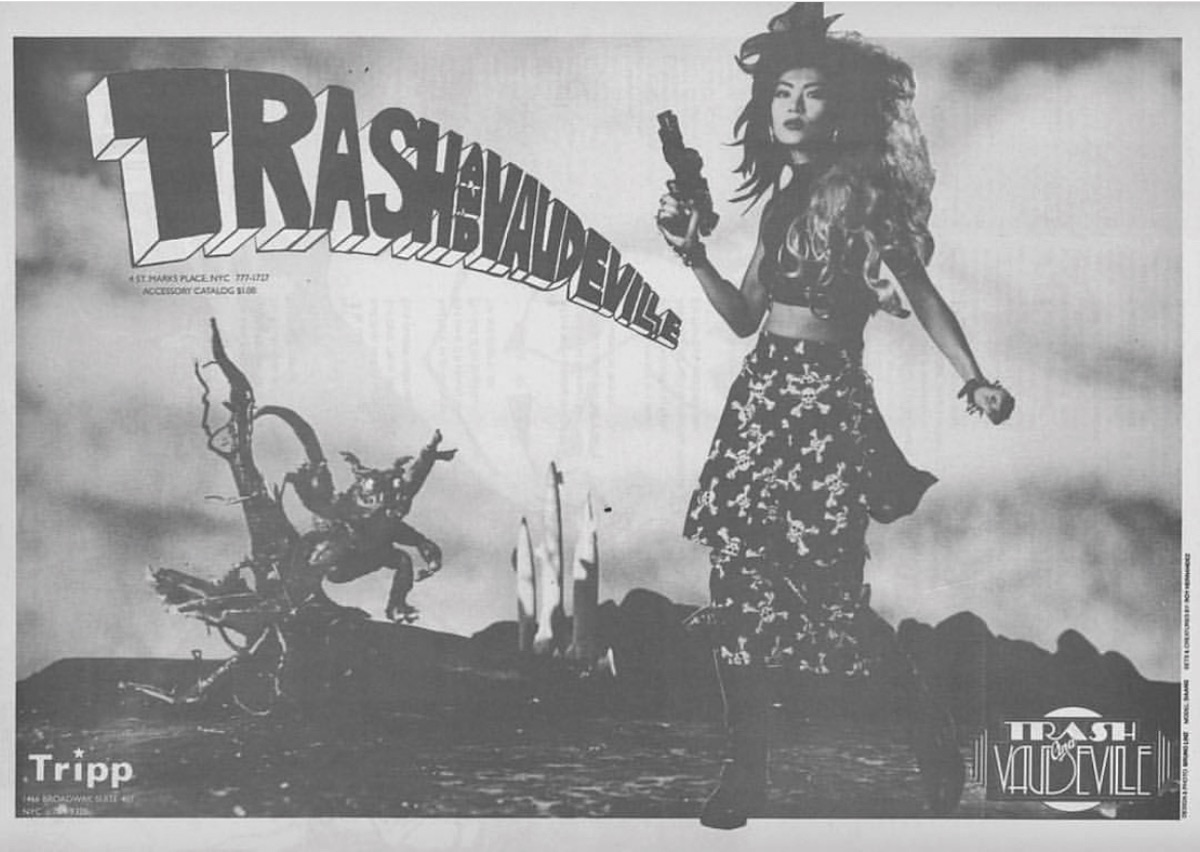

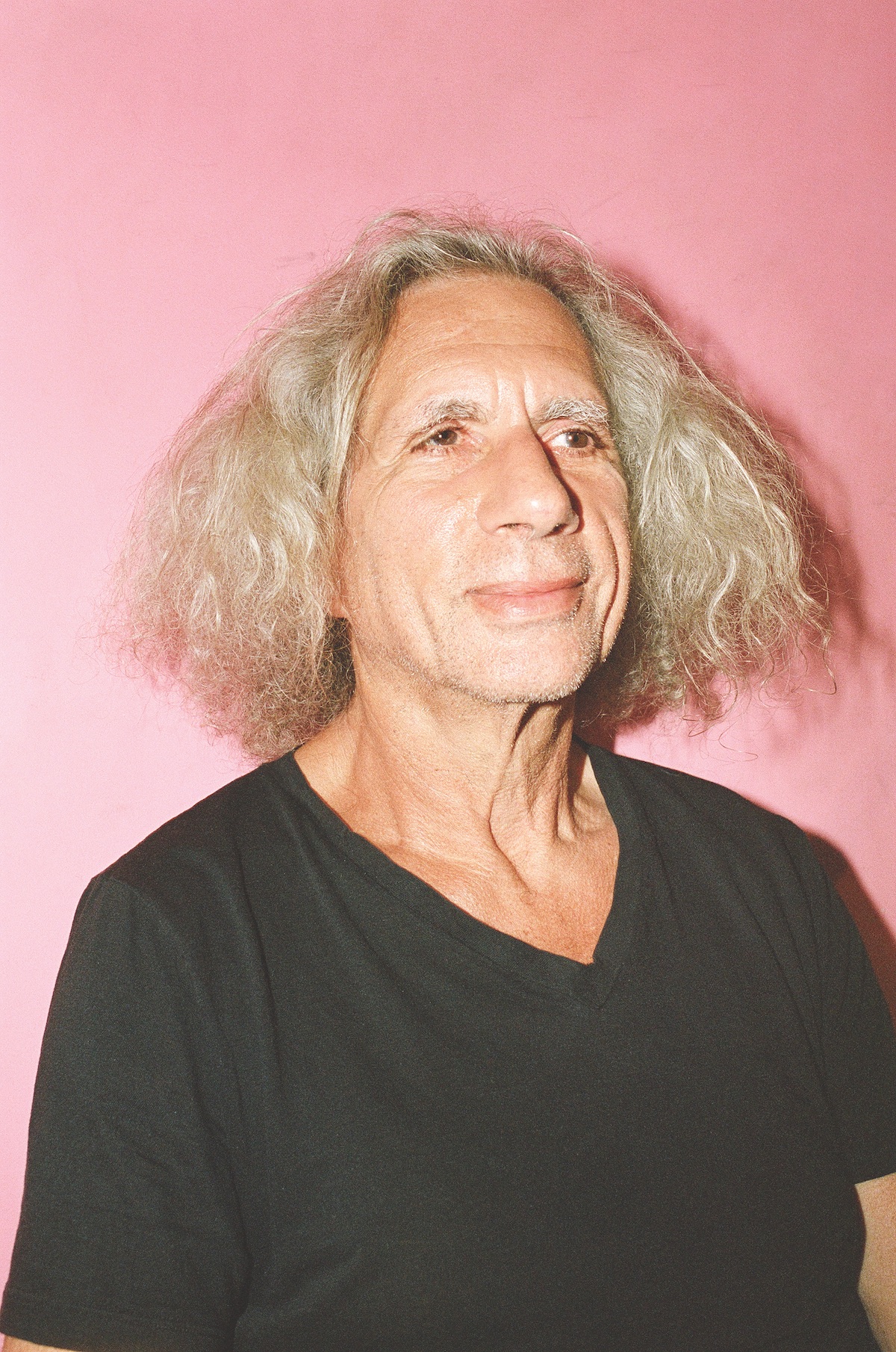

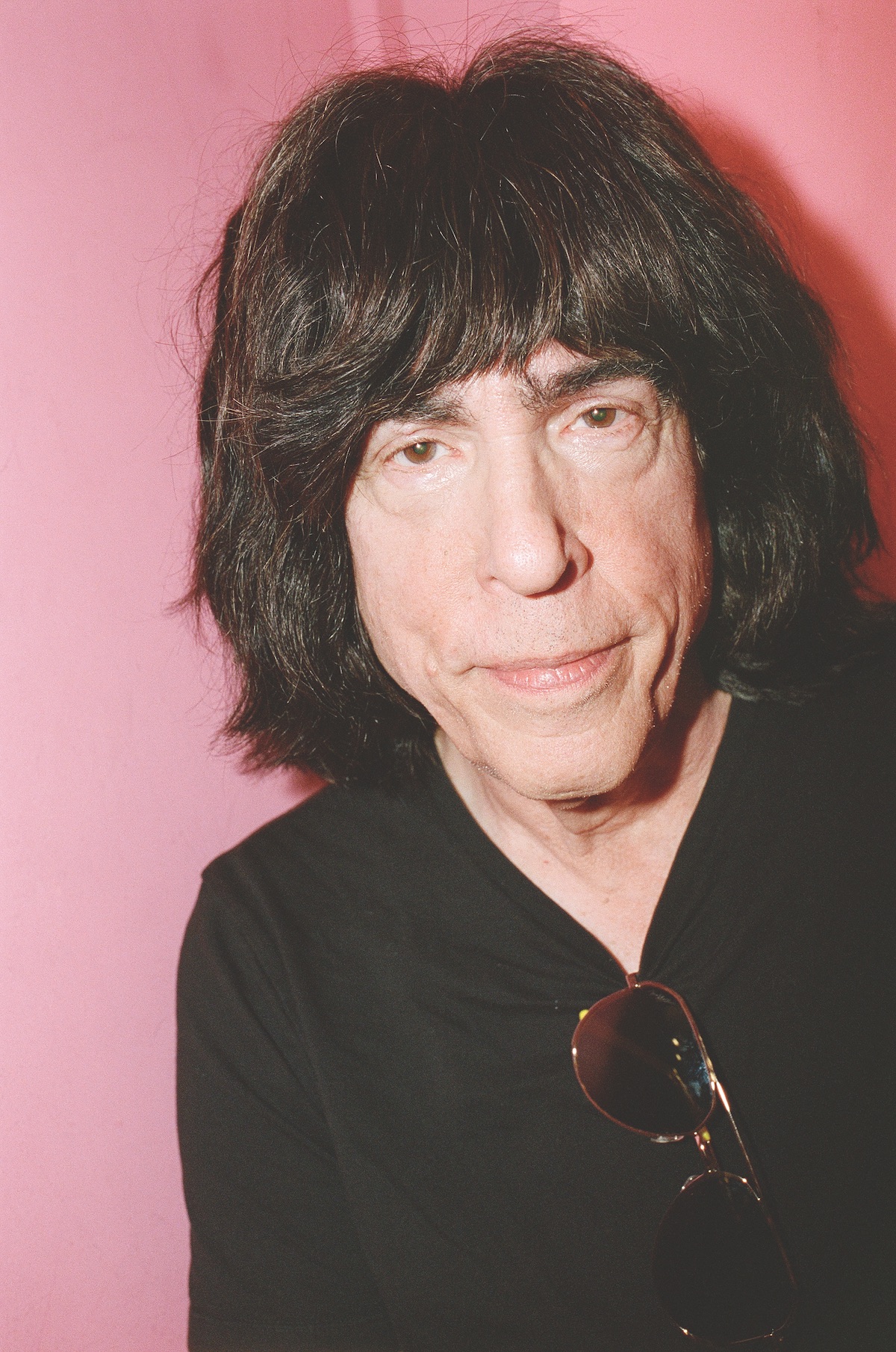

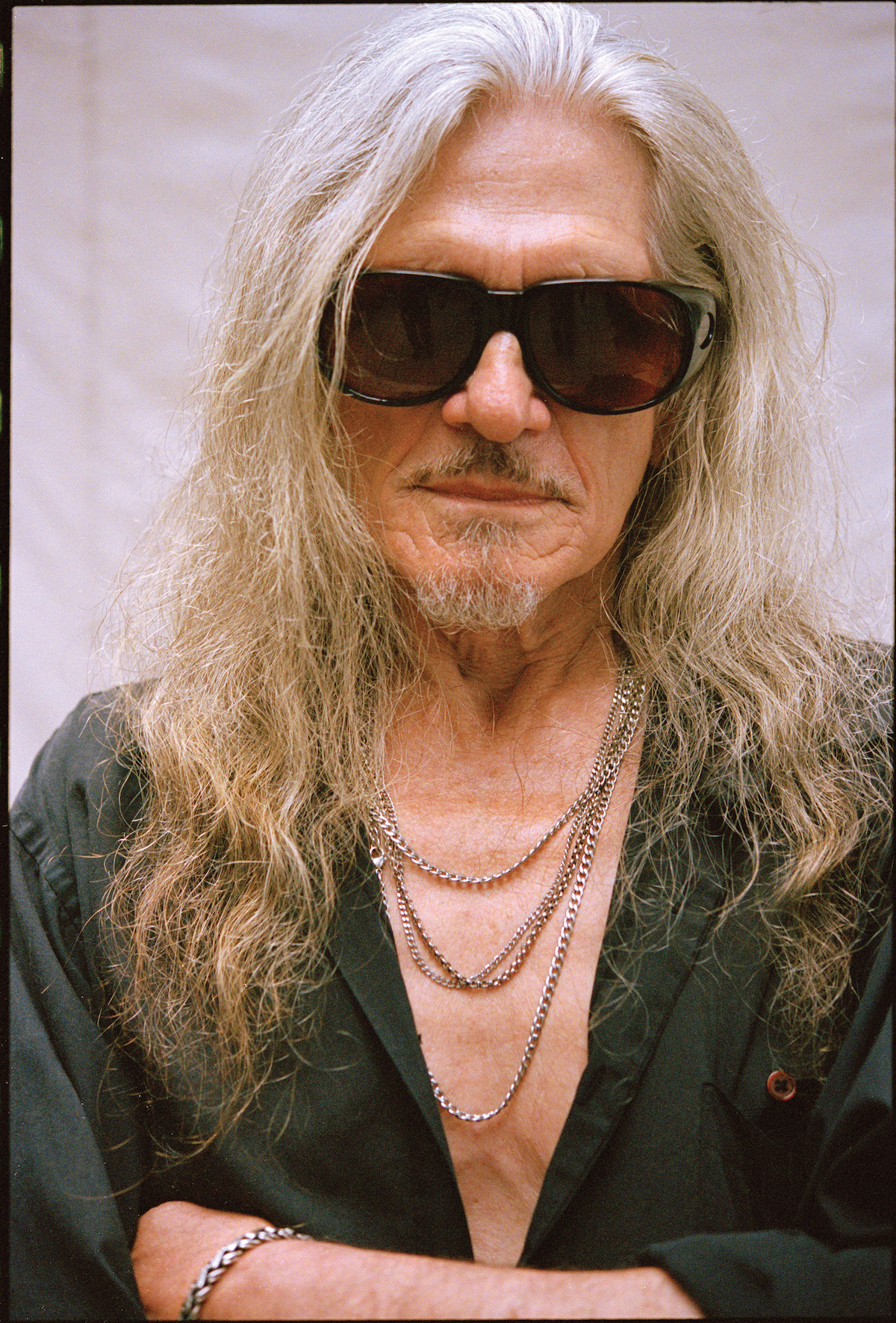

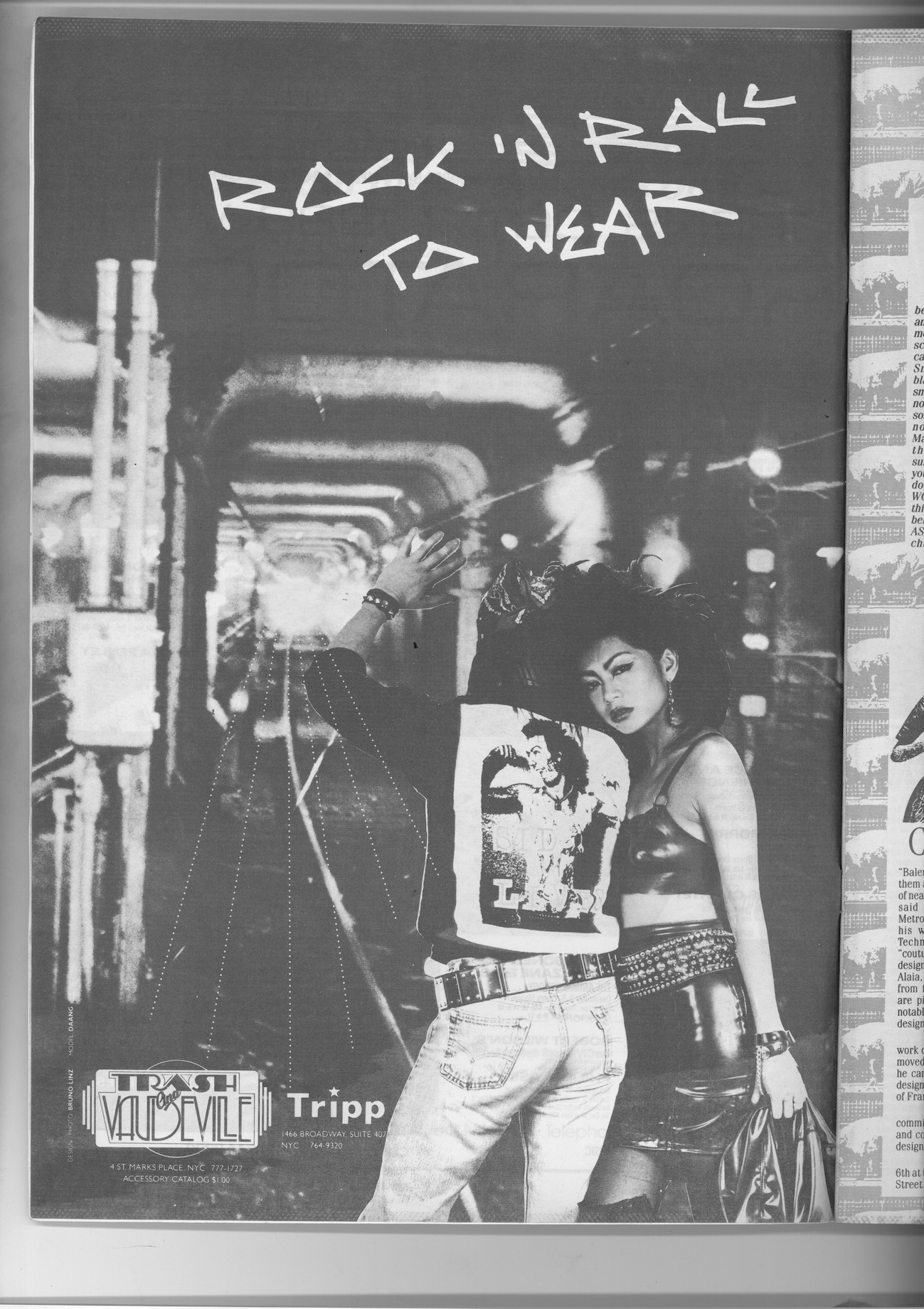

Over the decades Trash and Vaudeville has weathered cycles of cultural upheaval, economic instability, and waves of gentrification — the store eventually moved around the corner to East 7th Street in 2016, where they’re still going strong — with the support of the so-called “Trash family,” a faithful crew of multi-generational customers, colleagues, the occasional rock star, and eventually even some actual blood relatives. One of those rock stars, and a longtime friend, with his wife, of Ray and Daang’s, is Marky Ramone. Having drummed with the bands of punk pioneers like Jayne County and Richard Hell, in ‘78 Marky joined seminal punk quartet the Ramones, a band whose heavy-banged haircuts, biker jackets, and black jeans — provided by, who else, Trash and Vaudeville — were nearly as genre-defining as their amped up power chords and blunt, disaffected lyrics. So who better than Marky to join Ray and Daang to discuss the overlapping worlds of music and style, and the near fifty-year reign of the landmark shop that serves them both.

[Originally published in office magazine Issue 20, Fall-Winter 2023. Order your copy here.]

SKYLIN, 14

FRIDA, 16

PRINCE, 14

We're here at Trash and Vaudeville, a shop with, God, almost a half century of history. It's fashion history; it's New York history; it's rock ‘n’ roll history; it's punk rock history, and we're here talking to Ray and Daang Goodman, proprietors and the spirit of the shop. They've been with it for the long haul. Also joining us is the great Marky Ramone, long time friend of these two.

Marky Ramone— … and the other Ramones.

Yes, I’ve heard of them. [Laughs] So, welcome. I think we'll start at the beginning — or a beginning, at least. When you hear about New York in the mid-seventies it's a city on the brink. The city is going broke, there's crime skyrocketing, and unemployment. It was '75 when you opened Trash and Vaudeville. What was it like opening a shop in that environment? Did the shop play off of, or reflect that feeling in the city?

Ray Goodman— You know, I had just myself moved into the city. I was 21 years old. I really wasn't thinking of it in those terms at all. To be honest, I was just so happy to be there. I had been going to St. Mark’s for quite some time, and I guess being the age I was, I just never really looked at in terms of what was going on around me as far as the economic situation and the crime, I was more concerned with the music, what bands we were going to see, and things like that, you know? All the positive stuff that was going on.

And where were you arriving from, Jersey City?

RG— I grew up in Jersey City. Actually, my mother brought me to St. Mark’s for the first time when I was 13 to see an off-Broadway play down there, and I just remember getting out of the PATH train, walking down 8th Street, and when we got to the corner of St Mark’s and Third, looking around and saying, I don’t know what’s going on around here, but I just felt right. And that was it. I started coming on a regular basis. I just love it.

MP— So Marky, around that time was the shop part of your stomping grounds yet?

MR— This was the store. This was the store for everybody. All of the bands that played CBGBs and everybody hanging out in the city, you know, this was the look and it still is.

Did you get a sense of the challenges the city was going through at that time? Or were you like Ray, kind of in your own pocket of it and unaware of what was going on outside of that?

MR— Nothing changes, you know. It’s still the same stuff. The homeless, unemployment, the whole deal. But what did we do? We just formed bands and played to forget about that crazy stuff. We just put all of our energies into our work, and then CBGB started and the rest is history.

RG— The economic situation was tough and the neighborhood was going through a bit of a rough period, but that enabled me to rent the space at a price that seemed workable and realistic.

Did you pick up the space from a shop you were working at already?

RG— Yes, I had worked there for about a year and a half, stayed very good friends with the owners of the store that had previously been there, and let them know that if they ever needed me, I was around. And then one day, they all ended up retiring, the store was closing, and one of the partners offered me the opportunity to buy the space from him, which I did. I had been to London, and had this concept of a store that sold vintage and of course mixed in some new clothes. That was the concept we started with.

But you had a little bit of training in this as well. You had an education in merchandising from FIT. Did that help formulate the idea or was that just sort of a step along the way?

RG— I think it was more of a step. Don’t get me wrong. No, it was great. I shouldn’t say that. It was actually very important because that's how I got to go to London the first time. I got to do my practical work at an internship in London. So that did get me there, and that had a lot to do with my aesthetic and my style. So it had a lot to do with the aesthetic and my style, but my concept not so much. I went to FIT to appease my parents and to get a formal education, but I think I learned more in the year and a half that I worked at the store.

Now in the ‘70s Daang, what were you up to? Had you made it to New York yet?

DG— [Laughs] I was in Laos at the time.

And what brought you over to New York, or — it was California first, wasn't it?

DG— Laos fell in ‘75 so my family moved to Thailand, and I went to San Francisco for college in the ‘80s.

[Laughs] When did you first set eyes on this insane man over here?

DG— I think we met in New York. We were doing a trade show, like a boutique show.

RG— You know, we met at the show then we started this long distance situation. She was living in LA at the time, but there were lots of trade shows back then. You could almost be on the circuit, traveling every other month to some place for some show. Once our paths crossed, I would go to LA and she would come to New York and finally, when we realized that we wanted to spend time together, seriously, I asked her to move to New York and then went out and bought the ticket.

And you two connected on the two things that make Trash and Vaudeville what it is, fashion and music?

RG— Right, the thing is that my mind was blown when I first met Daang and picked up on her extensive knowledge of rock and roll. She knew so much, and that was one of the things that really impressed me and I realized that that's just how she was. She is very smart and she has that ability to come into a completely strange situation or environment and study it, learn it, master it, and then control it almost — in a positive way. And that was great.

DG— After we met, we always tried to make each other's dream come true.

That's very sweet. Marky, that’s why we sat you between these two. So they could flirt over you.

RG— [Laughter]

DAANG GOODMAN

Ray, it also sounds like you had some musical aspirations early in life, and it was drumming that you had your heart set on, right? And then we´ve got a successful drummer here — is there a little bit of living vicariously through Marky?

RG— Yeah, absolutely. I mean, obviously I realized early on that drumming was not gonna happen for me. I had friends and people I grew up with like Clem Burke, the drummer from Blondie, that were doing it. But it wasn’t for me. My whole idea was to stay close to the scene so I figured if I’m not gonna do that, what are my options? At that point, I started doing some psychedelic lighting shows for a little bit, then I got into clothing and we started with selling rock and roll T-shirts and I figured that there was a shot in that. I liked working for that store. Basically being a groupie at heart, I loved the idea of creating this store that hopefully would attract those musicians and entertainment people I wanted to surround myself with.

Like Marky said, it was the store, it was the look, it was one of the nexuses. If you’re not at a show that night, then where are you going? This is one of the places that those people would flock to, which is great. You talk about the “Trash family” and it does sound like there's so much of that, just being in each other's orbits, and keeping the fashion and music scenes kind of overlapping.

DG— But with Marky it was different, it was family at first sight.

MR— I knew that we had something in common just looking at the clothing and the music and so we stuck together.

RG— We hit it off.

MR— My wife Marion is best friends with Daang.

Marky, tell me a little bit about how you first got into the New York music scene. I know you played in bands before joining up with the Ramones. First of all, how did you start drumming and what inspired you at that time?

MR— Oh, I was 12 years old? I saw the Beatles on TV, and I wanted to be Ringo Starr. As time progressed, I liked other drummers, and so I figured, let me start piecing together a drum set. So, the first band I was in was called Dust and we did two albums. And then I figured, you know, let me hang out in the city. So I started hanging out at Max's Kansas City. Then CBGBs opened and I went back and forth. Then I started playing with Jayne County — Wayne County — then I joined Richard Hell and the Voidoids making The Blank Generation album. And then Tommy Ramone, who was the Ramones’ first drummer, was leaving. He wanted to produce. So he and Dee Dee Ramone asked me to join the Ramones and I saw them at CBGBs. When I knew Tommy was gonna produce, I knew they were gonna get a good sound so, I stuck with it and that was it. And then I became Marky Ramone. You know, I just had to get used to it, but then everything went nice and smooth.

MARKY RAMONE, RAY GOODMAN

Was it much of a transition for you to take on that role and become Marky Ramone, and did fashion have a little bit to do with that?

MR— Well I grew up in Brooklyn, and I always wore a leather jacket you know, jeans and sneakers, so it was easy. You know, you don’t push it, you just get into it and let it ride. The next thing you know, people started getting familiar with me and it all worked, you know. I always say good things about Tommy. I always say good things about the other guys. I did 10 albums with them and did 1,700 shows, so something was right.

MP— Ray, these days so many celebrity musicians have a team of stylists and people to dress them and shop for them, and I’m sure plenty shop here. But I'm curious if you could speak to folks who have been friends of the shop or customers over the years that you felt really had their own personal style and something unique that nobody else was doing.

RG— First off, the Ramones. Going to see them live, going to their shows back then and even now when Marky's playing. It was perfect. They all had that look, they looked like a band and they looked like the music that they played. The Clash was a great band that had a look in mind. They would come in themselves, and were also very kind to the store, especially Mick Jones. Lots of people would come in.

Prince was a good customer to the store, he would come in on a regular basis. He'd pull up in his purple limo. I remember when the Cars first started coming in and they’d buy a T-shirt here and there, then they got signed and they went crazy. Patti Smith. Iggy Pop. Blondie, of course. The famous photographer Lynn Goldsmith brought Bob Dylan in one Sunday night, which was pretty amazing. He wanted to shop when the store was basically closed and he could just do his thing. David Johansen. The list goes on. That’s just how it was. People didn't have stylists, but they were portraying their personalities and how they felt through fashion as well as their music, so they knew better than anybody what they wanted to wear.

One of my personal favorite moments in the store was with Bruce Springsteen. I’m a big fan. He would come in quite regularly and one time he came in and as I said earlier, we did vintage clothing at that time as well. So I had found this perfect pink and black flannel shirt in the rags and it was in such poor condition that I couldn't even put it out. I dry cleaned it, and had somebody take the pockets off, and the patches off. It was crazy. And he came in and he just said, “Ray, you gotta sell me that shirt.” I said “No, it's a mess.” He said, “Please sell me that shirt.” And I said, “All right, you know what? Just take it. Have it.” And that's the shirt he ended up wearing on the cover of The River album. He sent me this huge blow up of him, “Dear Ray, thanks for the shirt, Bruce.”

Amazing. I'm sure there's a long list, but are there a few items over the years that have graced the racks at Trash and Vaudeville that come to mind when you think of stories like that?

DG— Marky wore the silver jacket.

MR— The silver leather jacket, like a motorcycle jacket. So beautiful. I wore that everywhere. Everybody would ask me, “Oh, where did you get that?” and I’d say Trash and Vaudeville.

RG— There are certain things, like our black jeans for example.

MR— I mean, my whole band wore them.

RG— And that was the first thing that we actually ever manufactured for the store because there was such a demand for it. People would come in and say, “Do you have any black jeans?” So I found a couple guys who had a little factory in Williamsburg, Brooklyn underneath the bridge; it was South 5th Street or something like that and they started making me black jeans. That was the first thing that presented us as manufacturers.

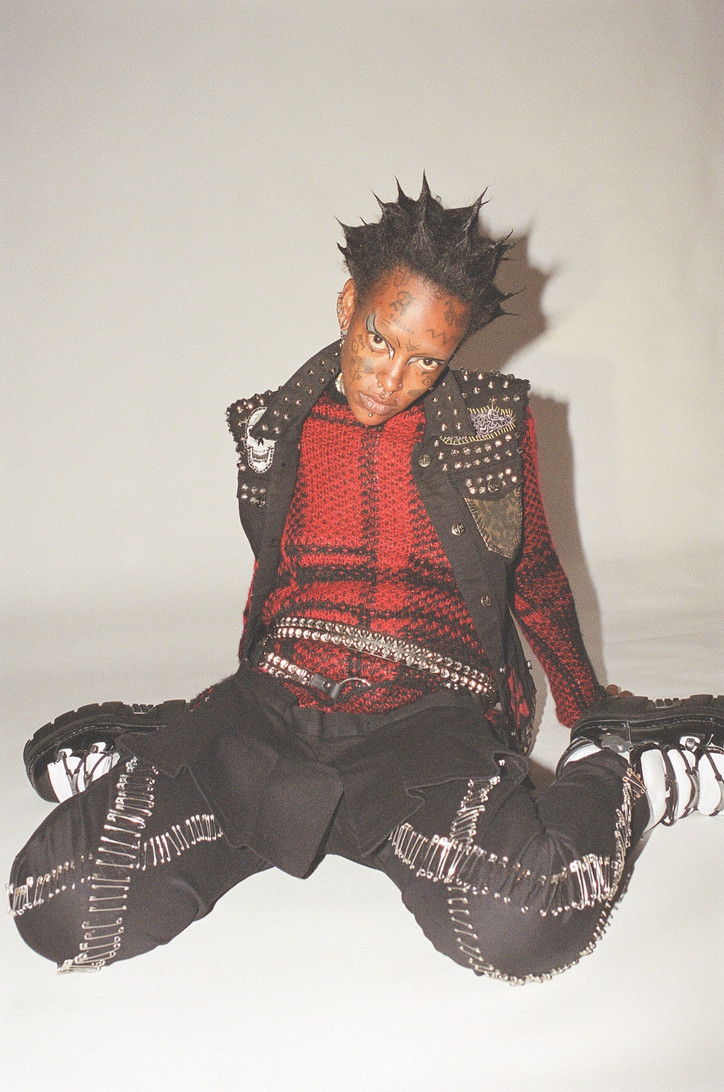

TINK wears FULL LOOK by TRIPP NYC courtesy of TRASH & VAUDEVILLE

It’s a nice segue, because I did want to ask about Tripp, when it was founded and when you decided that you wanted to be making more stuff yourselves. Daang, was there an objective to Tripp at the beginning or was it more of a creative experiment?

DG— When I moved to New York, I already always made clothes for myself. I’ve been sewing since I was eight. Ray liked the stuff I made and one day was like, “Why don’t you make a collection for the store?” and that’s how we started it. We would go to lower Broadway to buy fabric, sometimes go to Jersey to get things printed and then we found a factory, made 36 pieces and put it in the store.

RG— The impetus to do it was that we realized there was stuff that we wanted that we just weren't able to find, so we figured, let's make it so that somebody would come in and get inspired, or on the other hand, someone would come in and inspire us and we’d think, “Oh that’s really cool, we should have that in the store.” Eventually one thing led to another to where that grew into a really important part of the business and then we started getting approached by stores in other cities that wanted to stock Tripp.

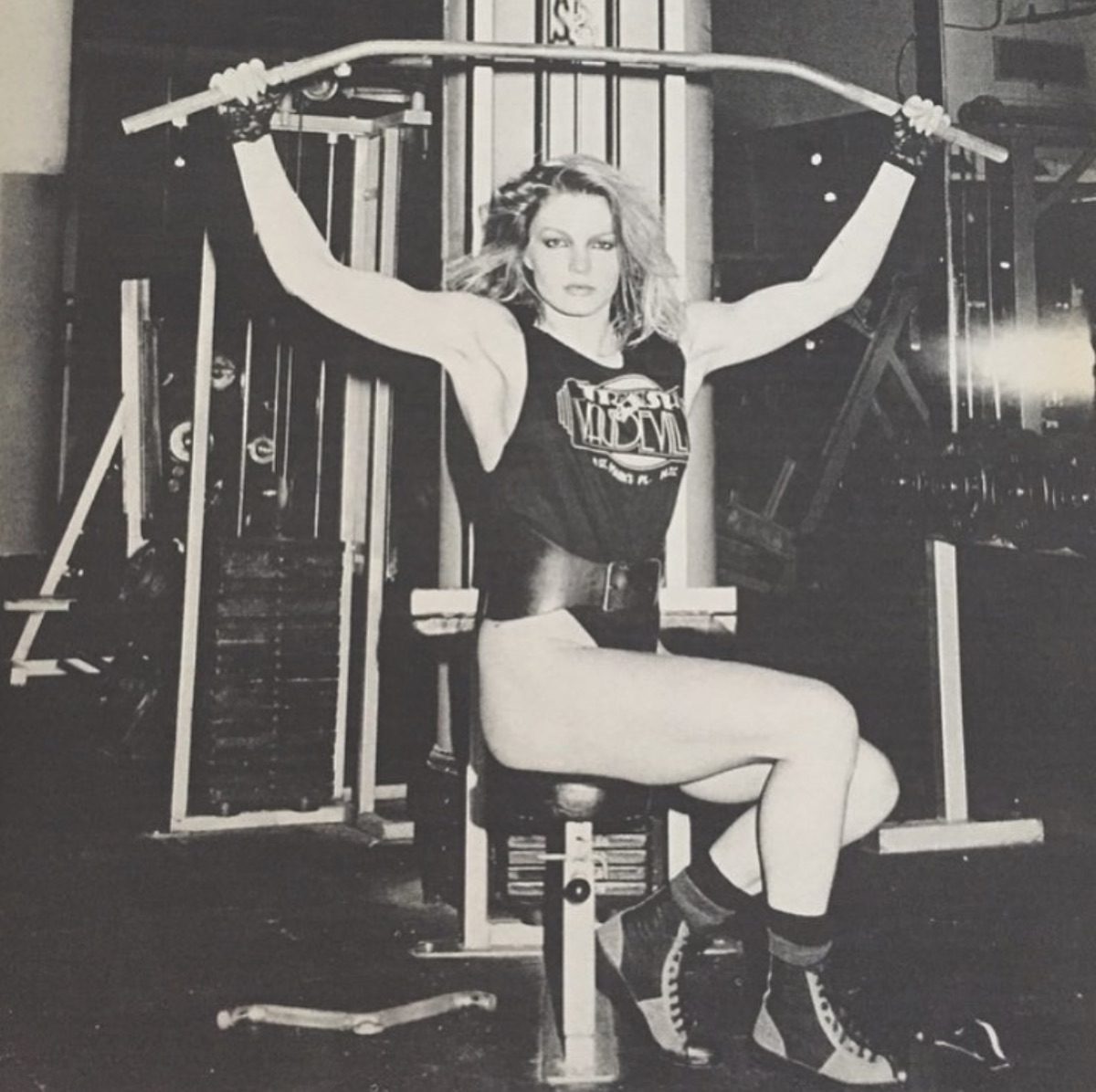

DG— We got a cover at Detail magazine. Annie Flanders [the editor at the time] put it on Boy George, the buckle skirt with a leopard print or something like that and then we went to the release party and Suchi [Asano] — at that time she was Iggy’s wife — was wearing a Tripp snake skirt and we became very good friends too. At that time a lot of girls were wearing Tripp and now it’s a lot of guys, like now we do 50% menswear. The thing about Tripp is that it doesn’t wear you, you wear the clothes. It’s about the artist. I think that all of the Tripp and Trash customers are artists themselves. They’re creative and they appreciate the work that goes into every piece. It makes them feel like themselves and the adjustable details allow them to express themselves.

RG— Our approach has always been: “This is what we have, you put it together the way you see it.” 99% of the time their visions look amazing.

REEF wears FULL LOOK by TRIPP NYC courtesy of TRASH & VAUDEVILLE

So, in a landscape that is trend-based, what helps the staying power of a shop like this or of a band like the Ramones?

DG— Well, we wouldn't be here without our kids. We have two kids, our son Lucas and our daughter, Cassie.

RG— Cassie really keeps us current in the modern world, whether it's with the ecom business, and also all the photos, all our social media, even style input. As we're getting older and everything, you know, we really need her in there. She's been working with me since she was six years old.

DG— Our kids grew up at trade shows, traveling with us for business, and they’ve always had a lot of inspiration and a lot of influence in our lives.

RG— And our son Lucas, he has a band, Lion Babe. He was a music industry major at Northeastern, but he spent summers working in the store when he was going to school. He has been very influential on the store.

And when it comes to the Ramones, the music speaks for itself. I mean, it doesn't matter where you come from. I don't even think you have to understand English to understand it and get into the energy of it. And it’s fun, it makes you want to jump up and move.

ELLIOTT, 24

Marky, in your experience, is that something you like to do? Are you altering your own clothes? Taking something off the rack and making it your own?

MR— Well what it is, I just wear clothes until I wear them out. [laughs]

I guess that’s altering the clothes, but sort of in slow motion.

MR— Well yeah that’s what I’m waiting for, is for them to wear out. Holes in my jeans, you know, just something that magnifies my personality. You know, you play live, you exert yourself and you do it every day. And the next thing you know, you get a nice pair of jeans, your jacket’s worn out, you can move. But Tripp’s everywhere. I travel all over the world and I see it and it’s amazing.

DG— And we are just beginning. I think just like with Marky's music, young people now are still discovering it. It’ll never die. It’s about that age, that same age — makes your heart beat when you hear it the first time. And now it’s even better, it’s not just the East Village, or New York, it’s everywhere. Like our clothes now have crossed over to rappers. Just the other day Lil Uzi was wearing it on the Tonight Show or something with the whole band.

RG— Daang has done custom stuff too, like for Rihanna. She did all the jumpsuits for Migos when they went on tour with Drake a couple of years ago. She did all of that and it’s so great. Everyone interprets it the way they want to wear it.

DG— So we stay at 1-2-3-4, stay the same. We keep the beat.

RG— Right, we’re not gonna wake up one day and say, “We're only making three piece suits.” What we make is going to be within our world, and in our world, we’ll experiment. It doesn’t always work so we try something else. We just keep moving and try to keep it going.

DG— I think living in New York City, a lot of people listen to people too much, care too much. You should do what you're happy with and be a good person and make stuff that you want to wear. You don't have to get approval from anybody.

RG— You have to be willing to put the work in. One slip, it's not the end of the world. You know, you just go back and rework it and do it again.

MR— I have a theory when I play the drums. I don’t usually make mistakes, but if I make a mistake, I'll try to do that same thing twice as if the first one I did wasn't a mistake.

DG— One slip is good, because you learn from it. You just stay at it.

TINK wears FULL LOOKS by TRIPP NYC courtesy of TRASH & VAUDEVILLE

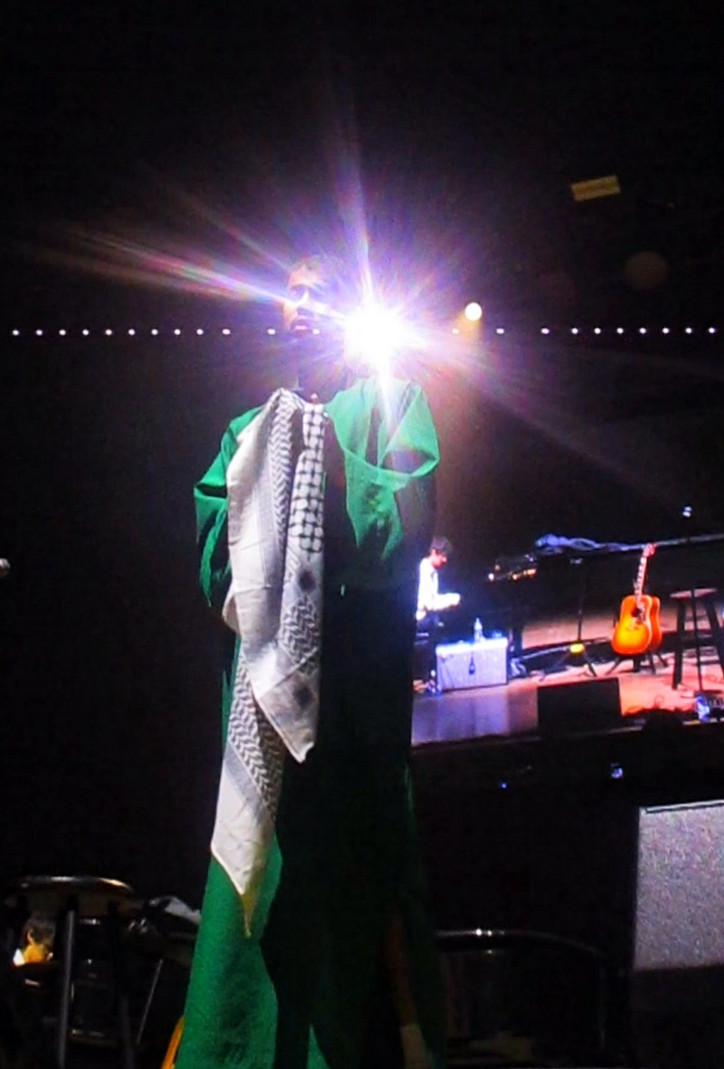

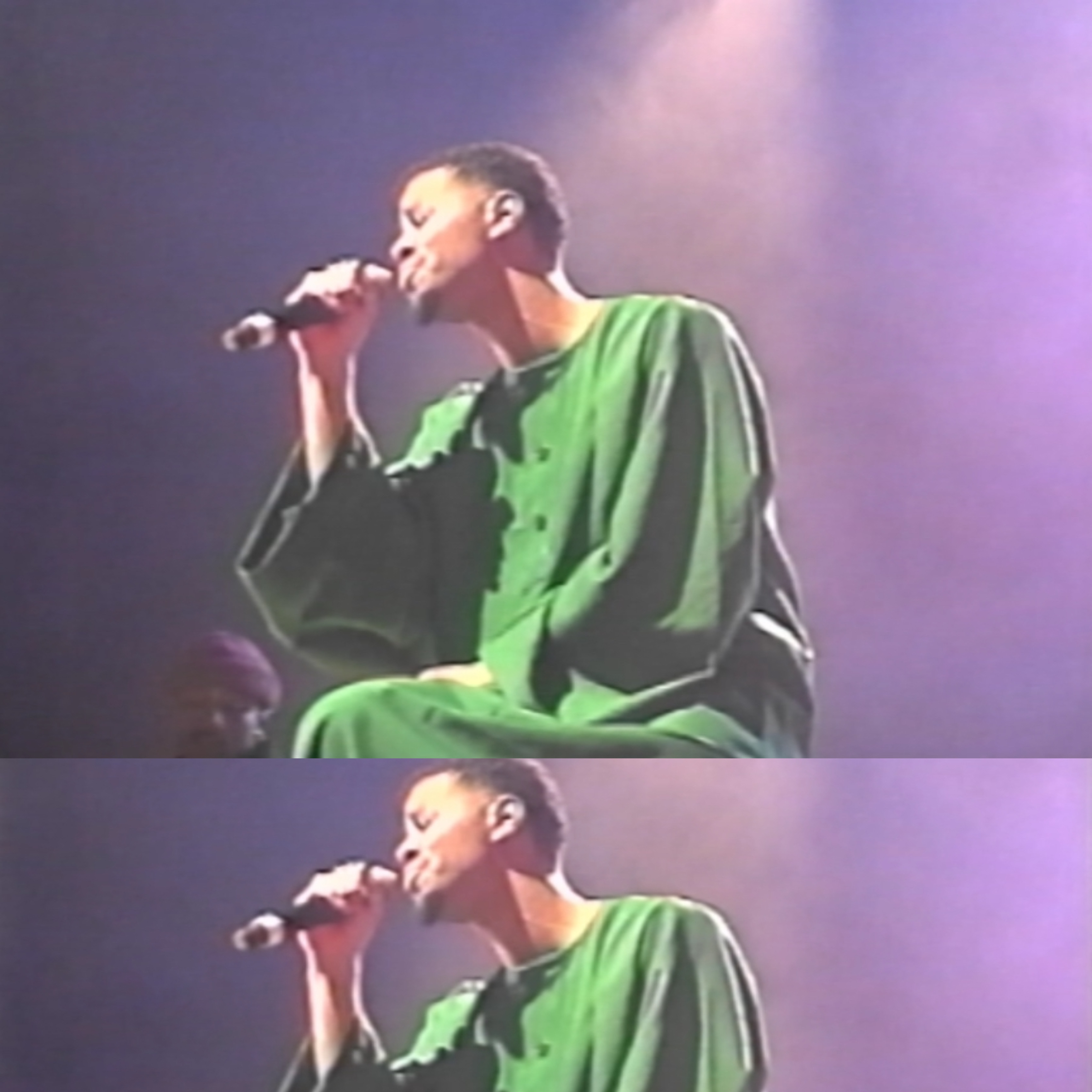

“He had a deep desire to begin a life there,” Mustafa says, describing his late brother. “My parents shared that desire with him. But the conditions of the war forced him back to Toronto, where he was murdered just six months ago.”

Mustafa didn’t bring that up for no reason. He acknowledged that everyone, no matter who you are, is connected to every war and everyone who dies because of it.

“We are connected to every genocide, and it will reach us eventually,” he says. “In my case, it reached me immediately, but it will reach us eventually. As Gwendolyn Brooks tells us, ‘We are each others’ harvests. We are each others’ business, and we are each other’s magnitude and bond.’ That’s what we are: here for each other tonight.”

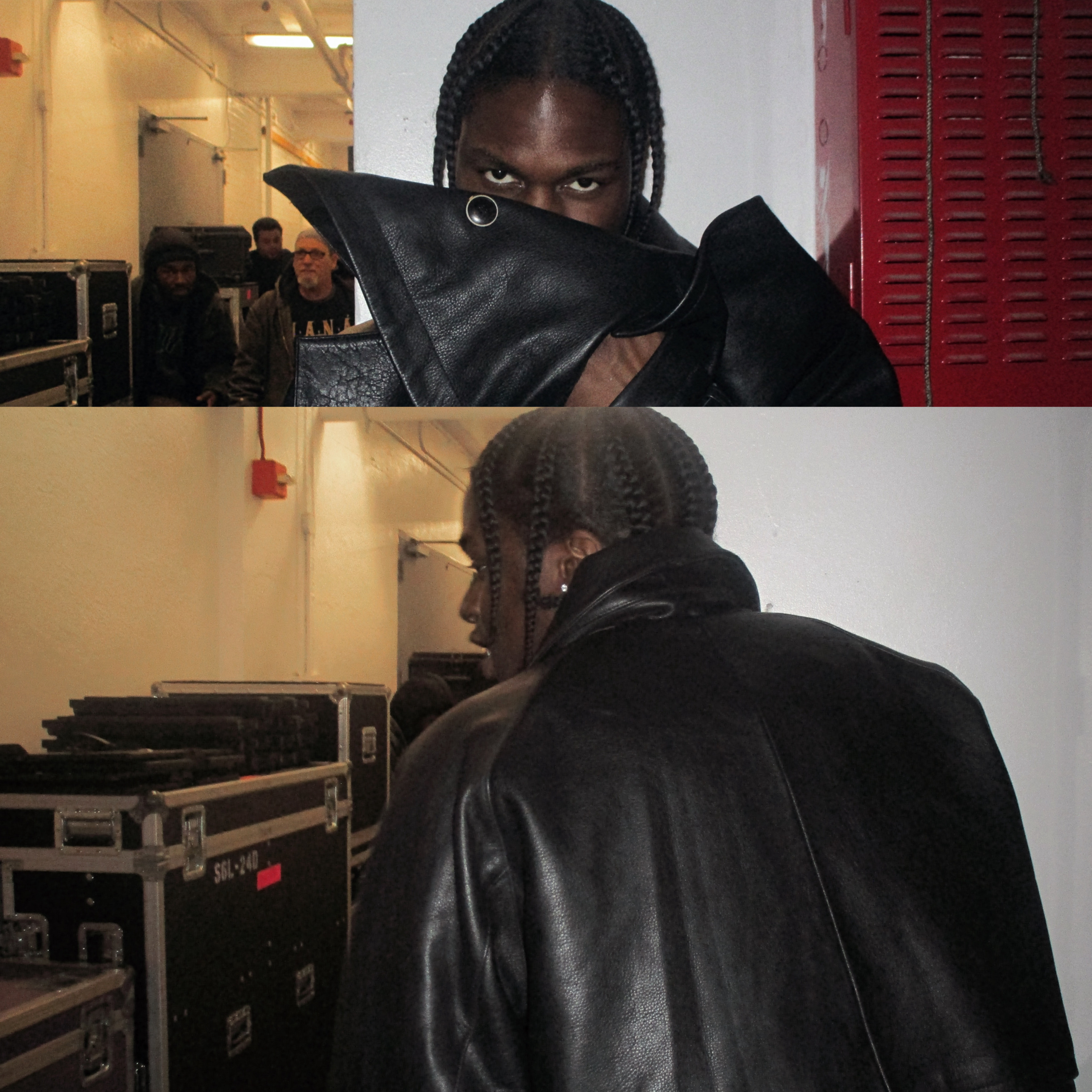

As lights shone down in the colors of Gaza and Sudan, the show began with spoken word from poets Hala Alyan, Safia Elhillo, and Clairo on the guitar. It left the crowd empathizing with the grief, resilience, and experience of those in Gaza and Sudan.

Each musician performed two songs on the acoustic guitar and the piano with gentle yet powerful voices. Clairo started us off by playing the acoustic guitar and a cover of Judee Sill’s “Lopin’ Along Thru the Cosmos.” Stormzy brought out some of his most gentle and soothing melodies, one song being “Holy Spirit” with his ethereal background singers.

6LACK performed an acoustic version of “PRBLMS” and a freestyle acknowledgment of genocide. Charlotte Day Wilson followed on the piano with her euphonious voice. The crowd went wild for Omar Apollo as he sang “3 Boys,” “Evergreen (You Didn’t Deserve Me At All,” and played the piano behind Mustafa's poetry. Mohammed El Kurd lost his passport so he couldn’t perform. Instead, Mustafa recited El Kurd’s poems on his behalf — and powerful was an understatement. Mustafa held a keffiyeh to symbolize empowerment and endurance throughout the genocides, then performed his own song, "Name of God."

070 Shake then took her hometown stage to perform her verse on “Violent Crimes” and a softer version of “Skin and Bones.” The crowd couldn’t contain themselves when Daniel Caesar performed his hit song “Best Part” on the guitar and had the crowd sing along to the impressive high-note parts that no one could hit except himself.

The show neared a close with a belting, heartfelt performance by Palestinian-Chilean singer Elyanna as an instrumentalist played the oud, an Arabic-stringed instrument. Nick Hakim sang and performed two moving songs on the piano. Palestinian rapper MC Abdul brought the crowd to life with his raps about occupation, dislocation, and genocide. Comedian and actor Ramy Youssef ended the show with a lighthearted comedy set to lift the crowd's mood.