Regular Guy

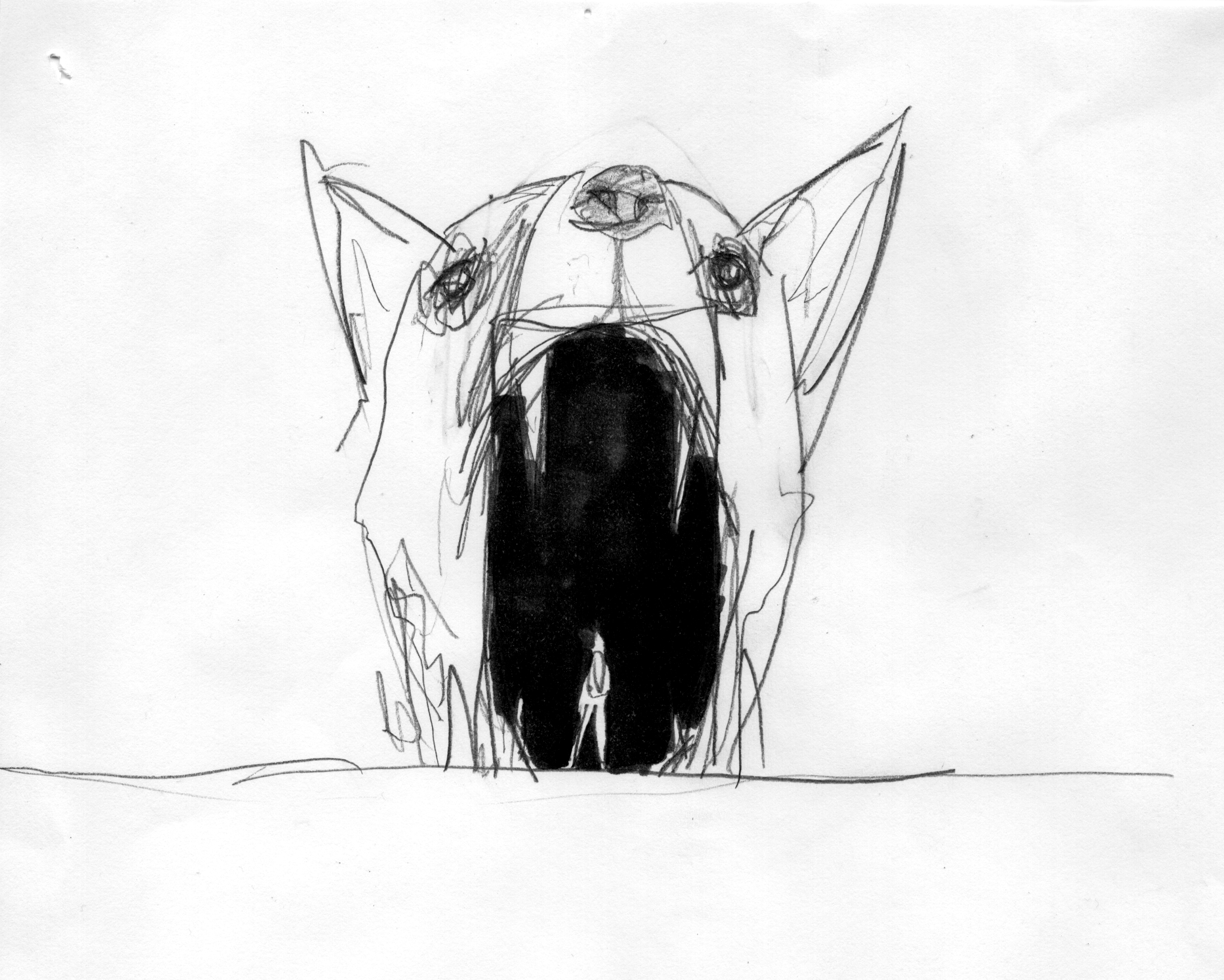

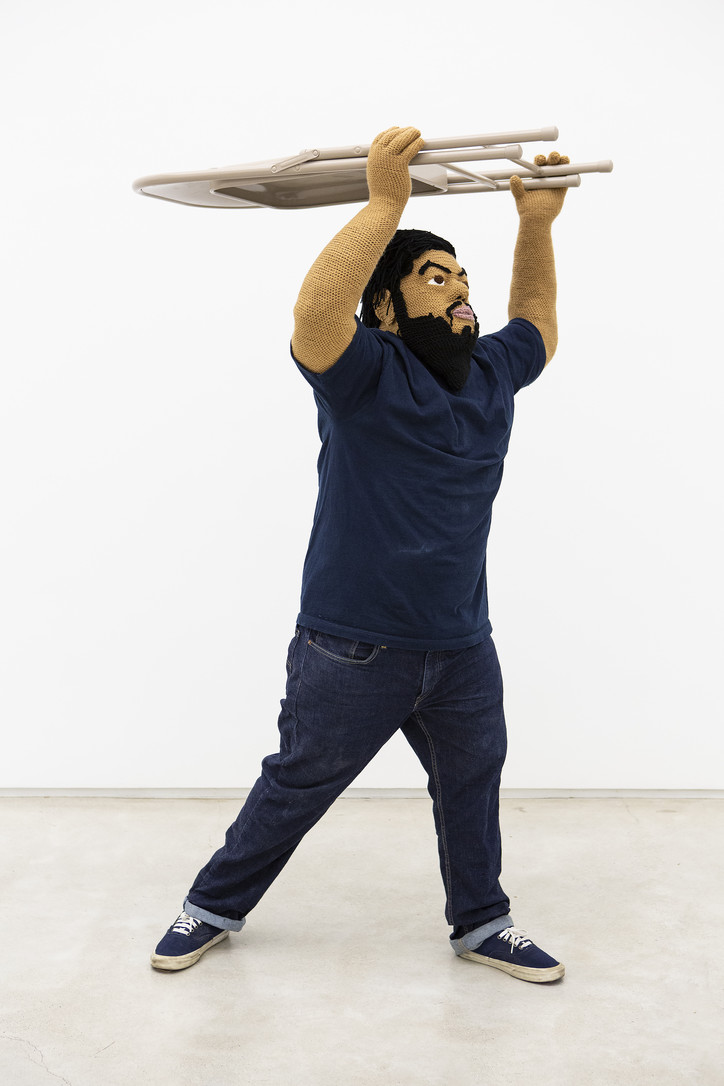

When I asked if this was weird for him, to see himself in so many different iterations, he replied, “It's weird in the sense that they feel like they're alive all the time. I walk into the studio sometimes and, especially if I just finished one, it'll be like, ‘oh fuck, who's there.’” This was my feeling, exactly.

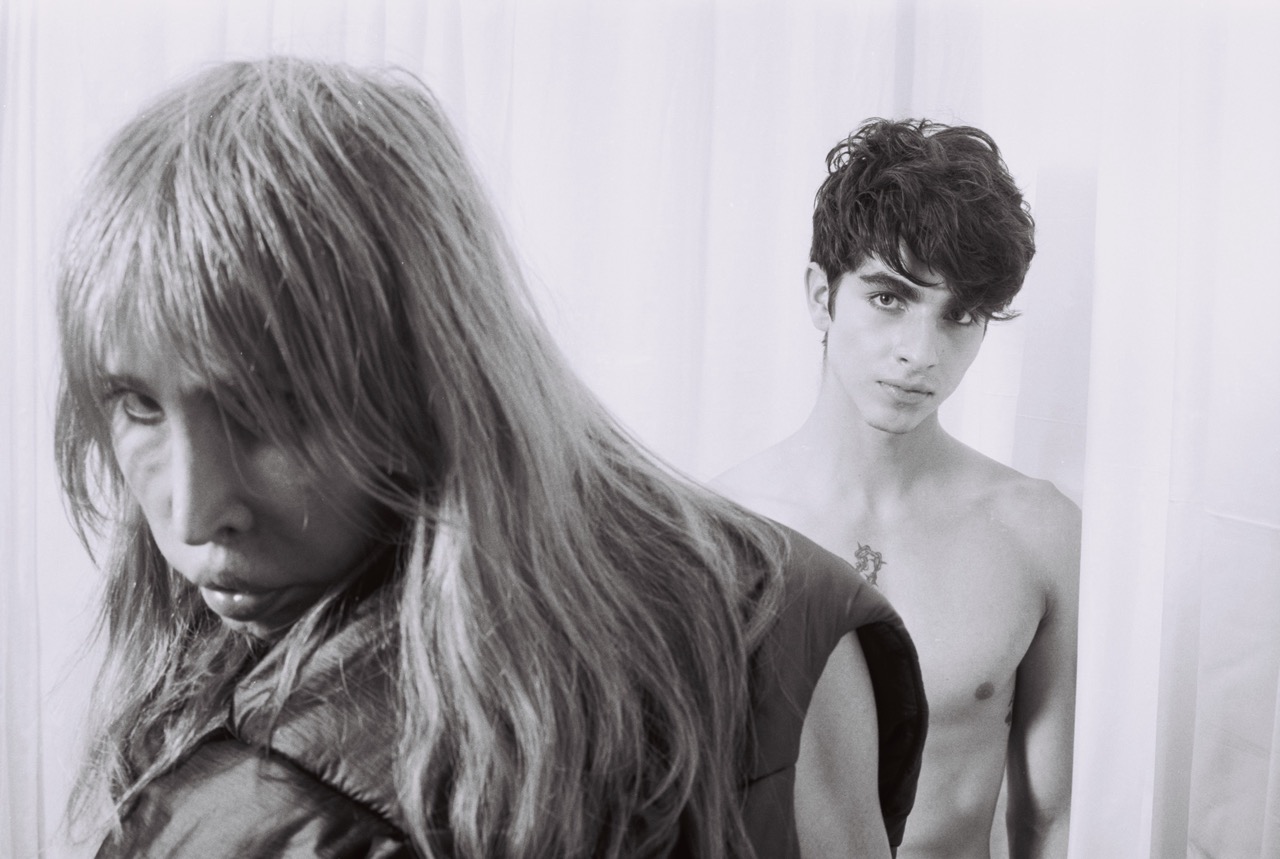

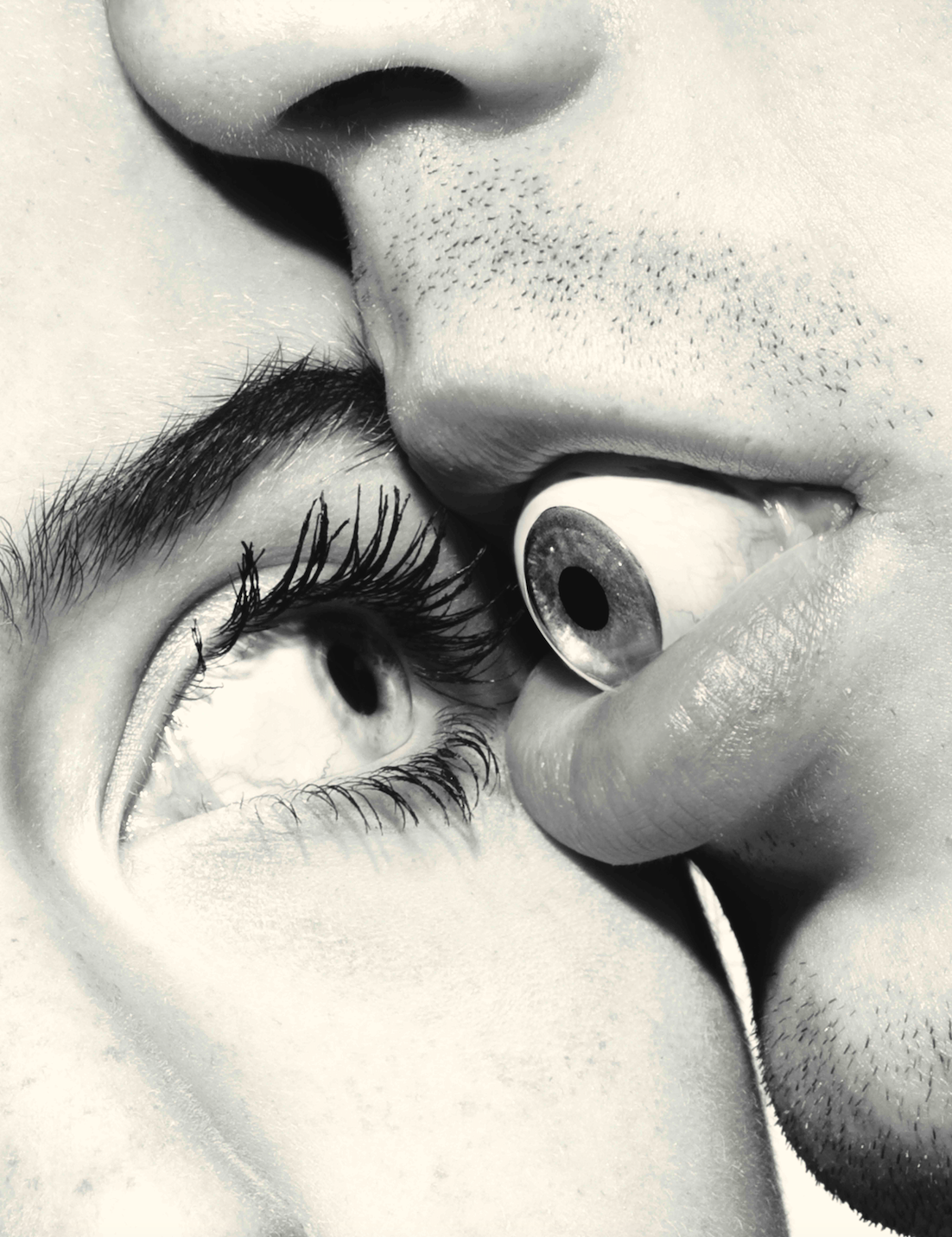

The installation is overtly violent, but in the canned, theatrical way of professional wrestling. The artist recalled to me how he would wrestle with his cousins when he was young -- “What's really interesting to me is this embrace that happens within wrestling, where you want to hurt them but you don't really want to hurt them -- it's really fascinating to me, this negotiation of how far you want to go, and how much you care for the person that you are up against.” The spectacle of pro-wrestling and the innate homo-eroticism, combined with a blatant homophobia within the audience, was also a point of curiosity: “It's really interesting to see these dudes cheer and go crazy over these oiled-up men who are doing these things that are very sexy and macho with these very sexual gestures.”

Professional wrestling, it would seem, appeals to that innate homo-erotic tension that lies just beneath the surface of all male relationships -- a kind of admiration, envy, and projection that is intrinsically connected to sexuality and prowess, but dances along the border, never breaking through the barrier of being fully, openly homosexual in nature. And yet. Flores and I, as is probably the case with many American men, shared the fact that, as young boys, the men in our family would stage wrestling matches in imitation of the professional wrestling that was popular in the late 90s, via ‘WWF.’ “Do you remember Triple H in the beginning?” Flores asked me when we were discussing famous wrestlers we remembered, “When he was this very gallant gentleman? So, like that character is very much when I'm interested in: this juxtaposition of cordial presentation and then it's also very sexual.”

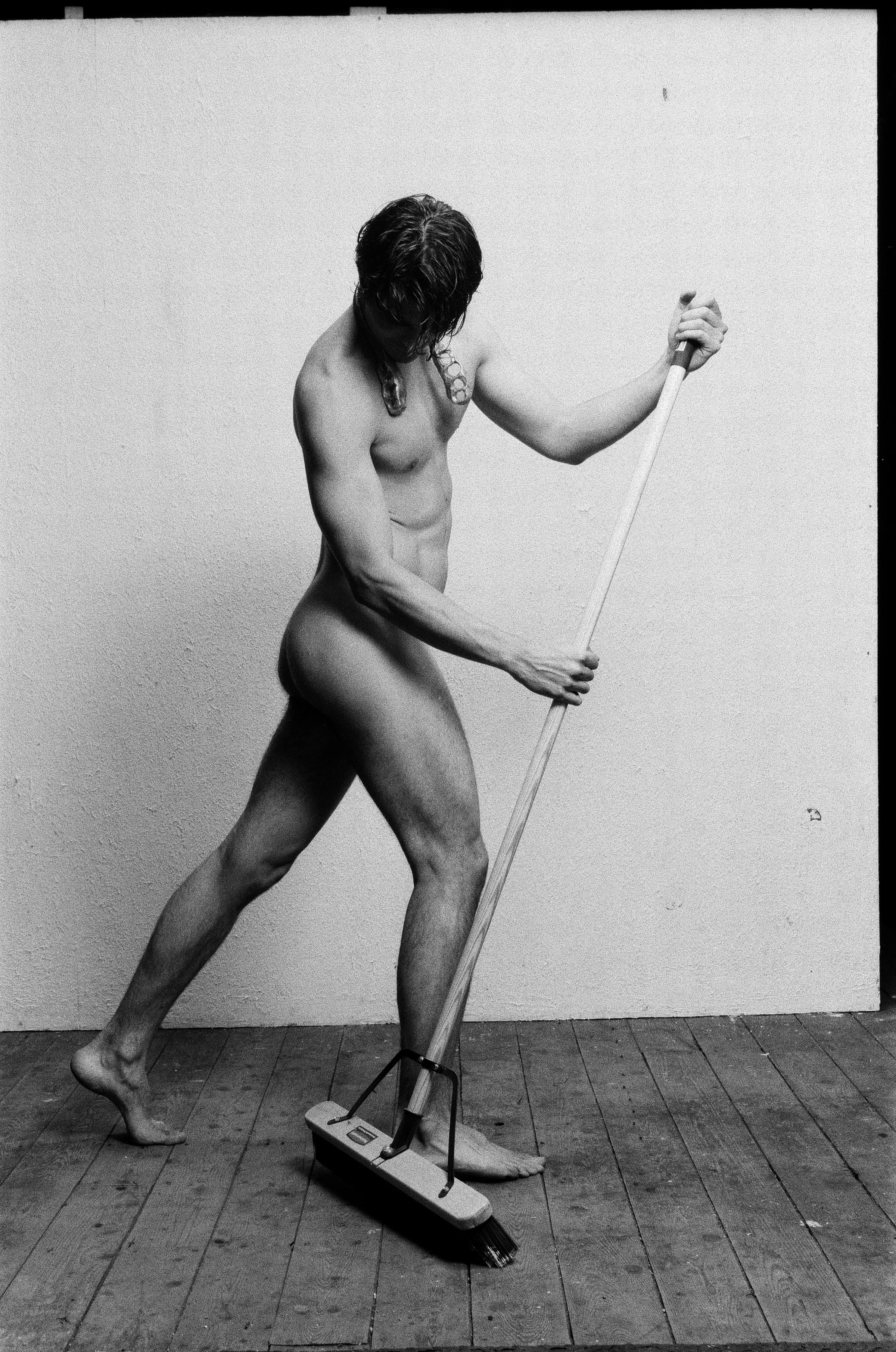

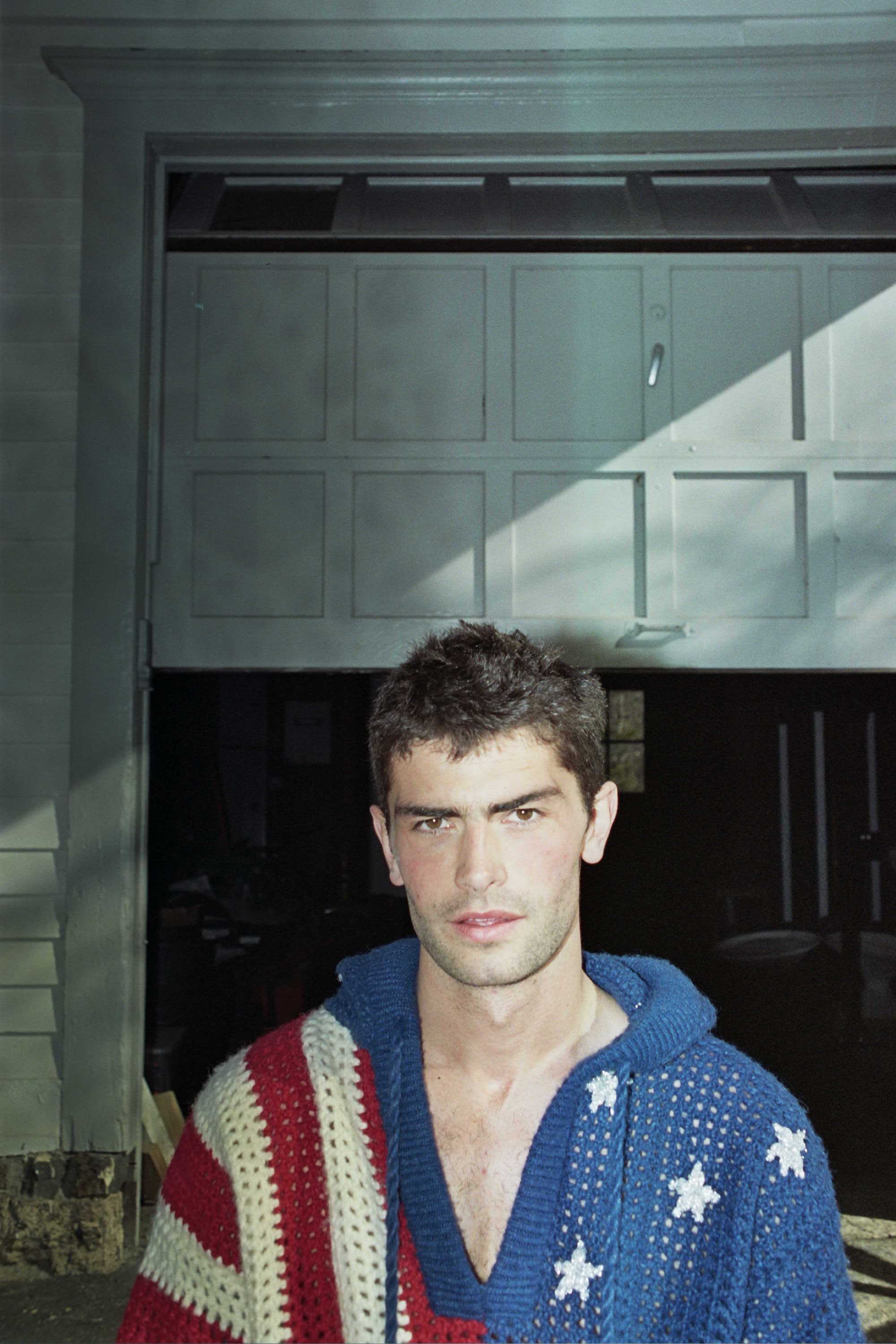

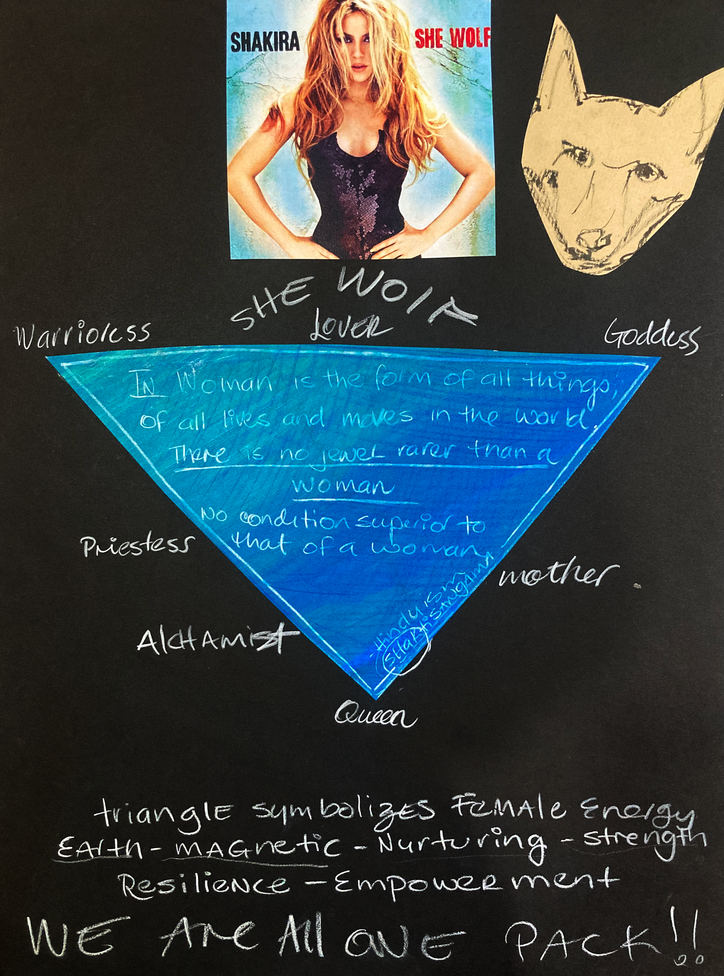

Flores wanted to poke at this bizarre crossroads of perceived masculinity, especially in connection to his own world and his own family. Interestingly, a female figure has entered the mix, standing at the entrance to the exhibit and looking on with an apprehensive look, "She's the first female figure I've ever made. That one has been throwing me off too because I keep thinking my wife is in the room, and I want to go up and talk to her. She’s supposed to be acting as a spectator, as an observer.” His wife is important to his process, wrapping his body in duct tape and creating a shell that will form the final sculpture. “Dealing with the topics I'm dealing with, the assumptions that come with that are a lot of people just assume that I'm gay, and I think that that's fine, I kind of like that, because I'm trying to break those stereotypes of what a gay man is supposed to look like or what a straight man is supposed to look like.” The outfit of the figures and Flores himself seems to land in this ambiguous territory in that it is so utterly plain. “That's kind of something I was trying to tease out with this uniform, it's a very regular guy-on-the-street thing that I really find fascinating. For me, I see myself as a regular guy, I want to be a regular guy and I wanted to mess with what that definition means.”

This seems like a question in the center of our larger culture at the moment, as well, this idea of being in between, but the weeding out of homosexuality within straight male culture still persists. “Vulnerability is a big thing for me, too,” the artist said, “Like not really being allowed to be vulnerable as a man. I want to be vulnerable with my male friends, be able to say, ‘I love you man,’ without having to say, ‘no homo.’ It's sort of ridiculous the way a lot of that culture functions. There's a lot of shit that I am trying to come to terms with through my work.”

'Another Thing You Did To Me,' is on view at Salon 94 through April 20, 2019. All photos courtesy of the gallery. Lead photo by John Martin Tilley.