Stored

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

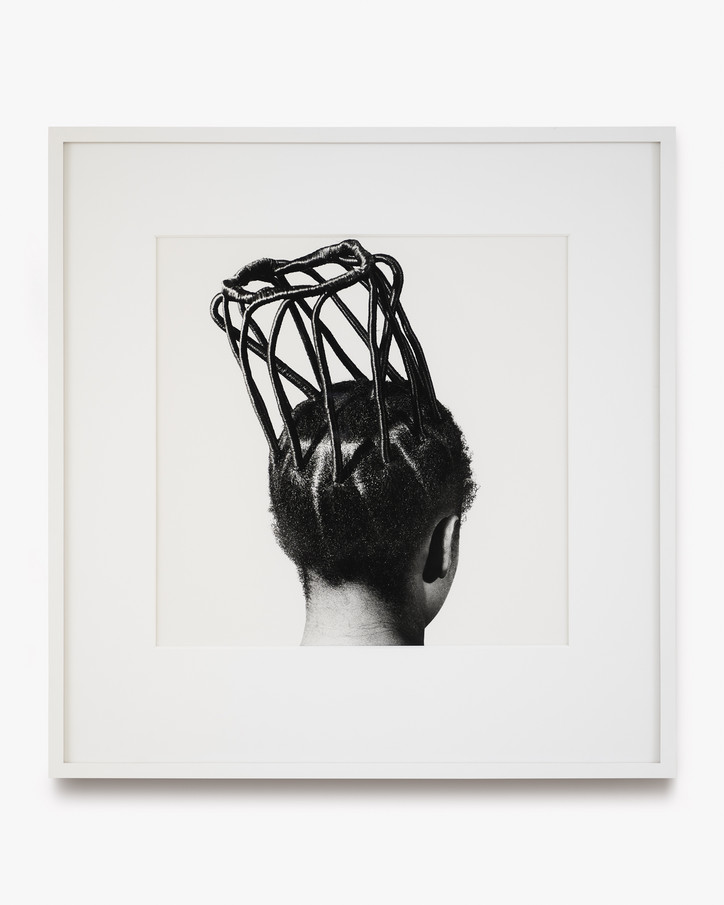

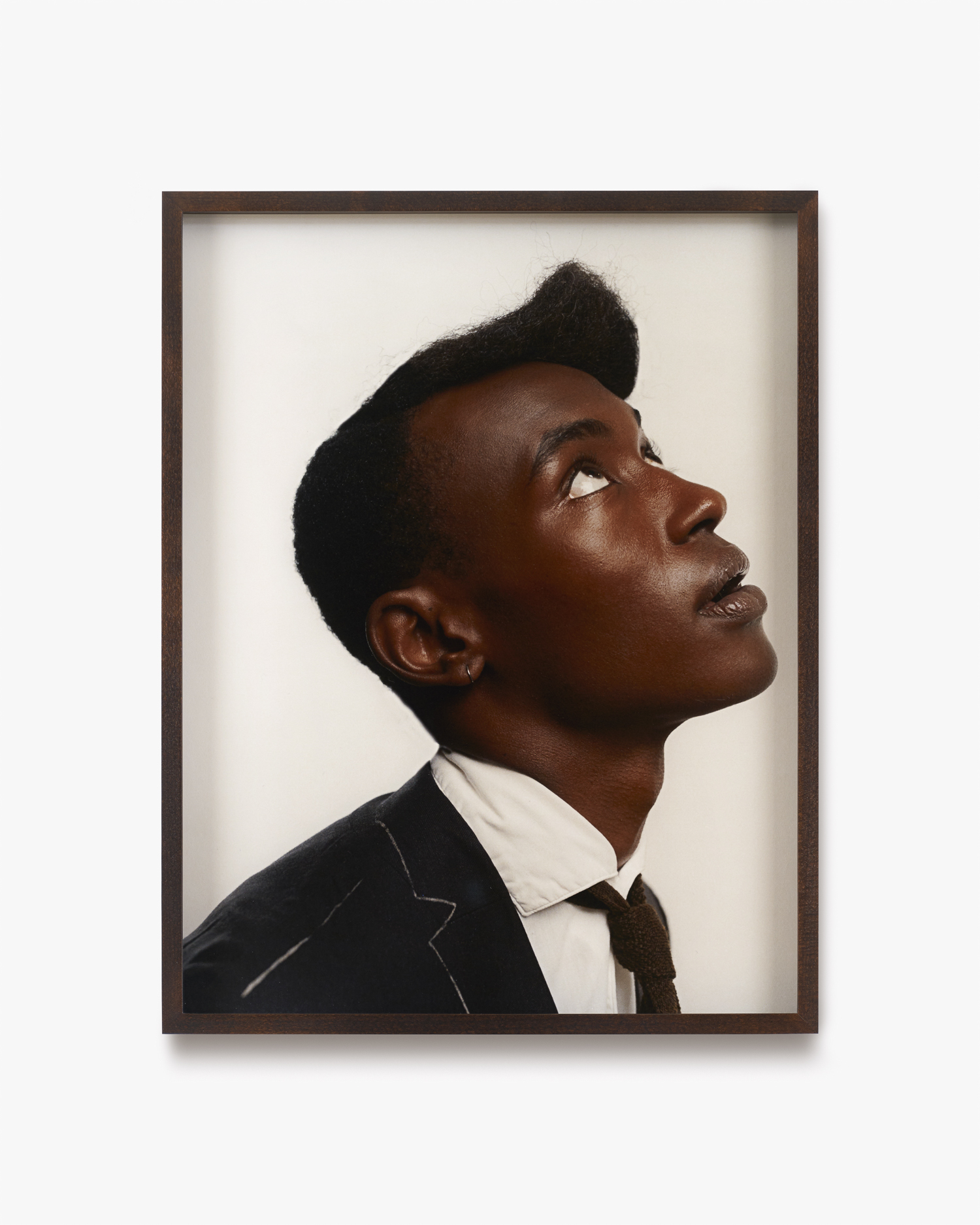

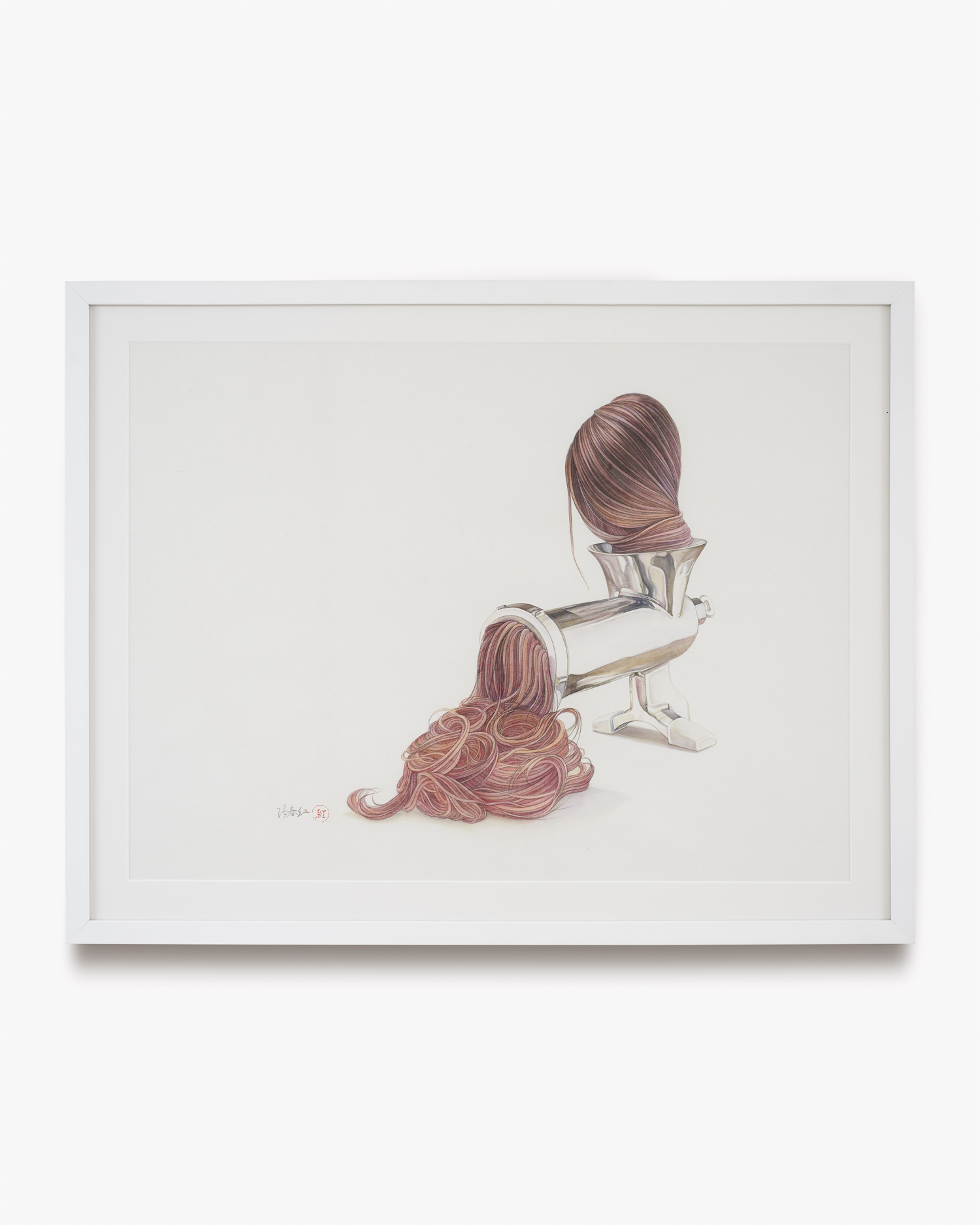

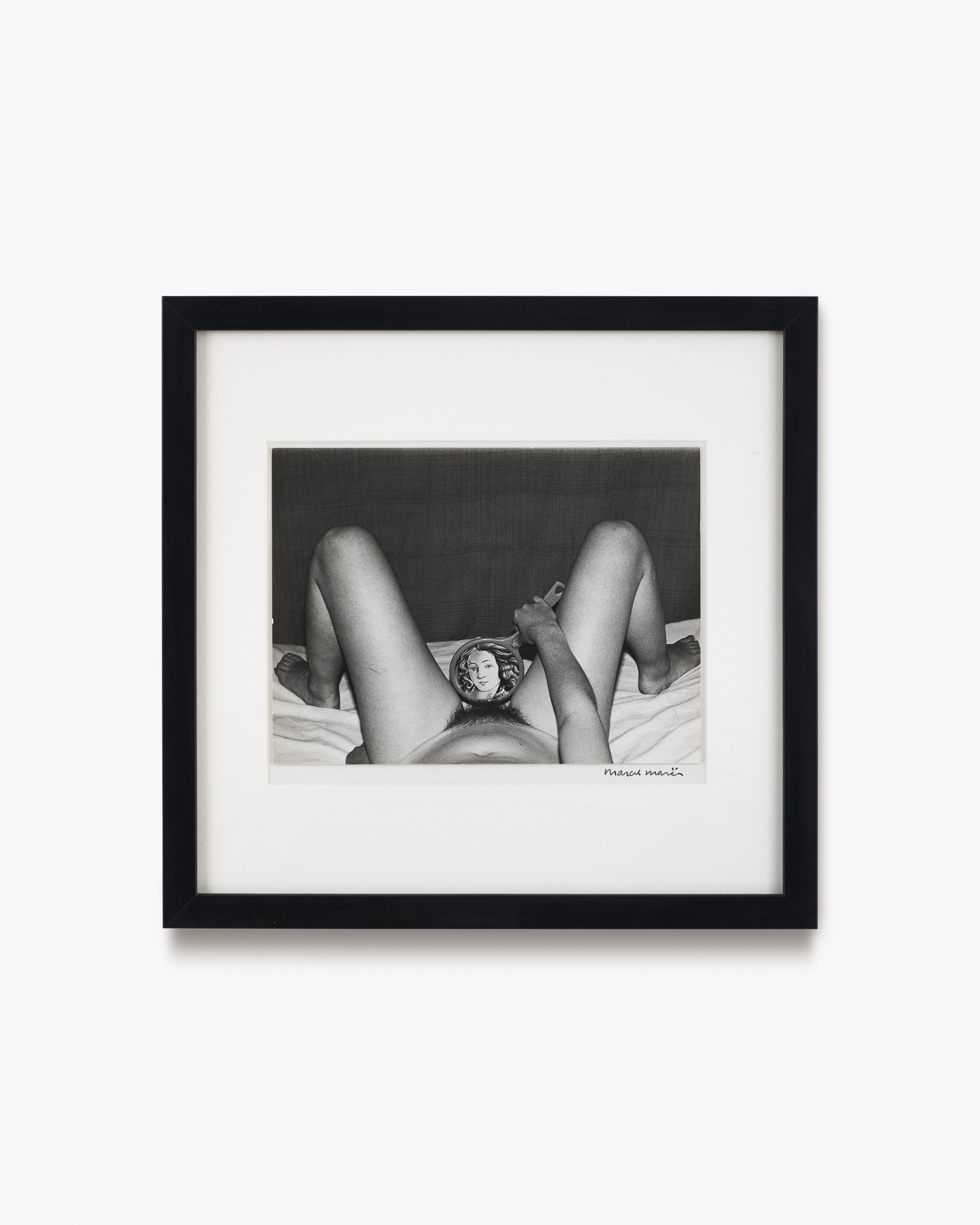

As Traore wrote, "...this show celebrates hair as a symbol of beauty, power and identity. That being said, the importance of hair is not exclusive to the Black community." Featuring artists like Camila Falquez, Hiba Schahbaz, Anya Paintsil, and Wangechi Mutu, the exhibition is a wide-ranging and diverse study of the personal, emotional, and cultural significance of hair across the human experience.

Traore and Huelskamp joined office to discuss the show, the role of digital engagement in the art world, and the curatorial page that started it all.

Brook Aster— Thank you both so much for making the time for this conversation. Jordan, I would love to hear about the first time that you encountered Hannah and her work.

Jordan Huelskamp— Hannah and I met through a mutual dear friend. My role as head of curatorial at Artsy is not only helping guide and curate experiences for people on Artsy —through personalization algorithms and curated moments for our audience —it’s also about tapping other tastemakers whose opinions and perspectives matter.

We launched this guest curation project in 2022, coming out of a time in which we were trying to engage our audience in interesting, digital-first ways. The art world was embracing these projects with a lot of gusto because we were in lockdown.

Hannah already has such a strong curatorial thesis for her gallery, and she was just the perfect person for this. It was so fun to work on this together.

Hannah, where were you in your career and in your life at the time that you were approached by Jordan to work together? And how did you come to a decision on the theme?

Hannah Traore— I was really excited about it because obviously Artsy is such an important platform. Before opening the gallery, it was a huge resource for me for research galleries and artists. It was such an honor to be on the platform in the first place, especially as such a new gallery.

I was just really excited and really honored that Jordan thought of me to do a project. I really thought long and hard about what I wanted the theme to be and ended up being really excited about the topic of hair. And if I'm not mistaken, Jordan, I think I'd actually given you three ideas and you liked hair the most.

JH— Yeah, that sounds right.

HT— I spent even more time than I thought I was going to, just because I got so excited and into it. Once you have issues with your hair — whether it’s aging, or a thyroid issue, or identity, or whatever it may be — you realize that everybody else also has these issues. Every time I would bring it up, it was like someone in the vicinity had a story or a personal connection.

Also, so many artists work with hair, but in such diverse and interesting ways. Some depict hair, some use hair as material, some use hair products or accessories, and then some use hair in ways that are so creative, I never could have thought it up myself.

When I first picked the idea, I hadn’t realized how broad the topic was in a really exciting and fun way. So I just got so into it, and then wrote a very personal essay about it as well. I was so proud of the outcome that I thought, “one day this has to become an actual physical exhibition."

JH— Hair is such a potent symbol as a curatorial theme. It is one of those elemental, human artistic motifs that we all use. Not very many people in the world consider themselves a true professional working artist, but I think everybody engages in art-making with their own body; be it their hair, how they choose to groom themselves, or body modification in general. We all are making these artistic and creative choices about how we want to show up in the world. And everybody has that experience at some point in their lives with hair.

HT— In the essay, I talk about the title “Don't Touch My Hair” and how the song of the same title is such an important anthem in Black Culture. As I did more research and also just talked to more people, I realized every single culture has some kind of spiritual, traditional, emotional, or political significance attached to hair. Individually, every single person has had an experience with their hair. Cutting your hair, shaving your arm pit…. It's all a choice, right? Even choosing to not do anything with your hair or to not shave your legs is a choice.

These decisions are decisions that we all make, whether they're subconscious or intentional. Hair really does absolutely bind us together.

Hanging on by A Hair, by Laetitia Adam-Rabel

Did you approach artists that were not a part of the original curator page for the exhibition?

HT— Yeah, quite a few actually. My gallery manager, Destiny Gray, who I couldn’t have done the show without, and I did a ton of research on artists. I also reached out to almost every single gallery on Artsy to see if they would be interested in consigning their work from the collection. Quite a few galleries did actually, which was really kind of them.

I would say maybe half the artists weren’t in the Artsy collection. It was an aesthetic choice, but it was also based on diversity of materials, diversity of cultures, and diversity of engagement with the topic. I was lucky that there were actually just so many options. And since opening the show we’ve found so many other artists that could have been included. There wouldn't have been space [to add more works], but we thought, “maybe we need to do a part two in a couple of years."

JH— It’s recurring; with these new experiences and some of the experiences that you shared, you will probably find more experiences to relate to, and then you'll discover more artists that speak to that, and then hopefully bring them into a future show. I hope we get another one of these.

Hannah, your gallery opened after the onset of the pandemic, in this era where people are so often encountering things online that they are then going to do later in person. How are you thinking about digital engagement in the art world? How does that inform the decisions that you're making as far as curating an online space?

HT— To me, the great thing about online platforms is that they have made art much more accessible. Obviously not everyone can come to see a show in person. But also, not everyone feels comfortable going to a gallery. One of the reasons why I opened a gallery is to try to make it as comfortable for everyone, especially people who look like me, but the reality is, for a lot of spaces, people don't feel comfortable going inside. It's very opaque, it feels like it's for a certain type of person. Having a platform like Artsy is super important for many reasons, and that is a huge one of them. I don’t fear digital life taking over because there's absolutely no way that the feeling of experiencing art in person could ever be replicated online. It's not a replacement and I don't think it ever will be, but it is an amazing way to reach a larger and more diverse audience.

JH— Yeah, an interesting thing about the art world is that most people do not encounter physical art galleries often, because they are not living in a city where that's normal. I grew up in Fresno, California. We had no art galleries, barely had a museum. It wasn’t until college that I really started to encounter the art world as the massive industry I recognize it as today.

Artsy can be that connector for people who don't have easy access to galleries in their city or in their neighborhood. When you look at the median distance of an Artsy purchase, there are thousands of miles between buyer and seller. Often, they're in different countries, so we are facilitating sales that probably wouldn’t have happened otherwise. Before Artsy, before the art world was online, you had hyper-local, regional gallery programs in markets that were strong, and you might only discover new programs and galleries if you went to an art fair — if you're lucky enough to be able to do that.

We are nothing without our gallery partners. We are in a symbiotic relationship. Everything we do is in the service of driving more interest from global collectors to our gallery partners.

Jordan, have you had a chance to see the show? I’m curious how this stands out from other projects you’ve worked on. Is this the first time a show has taken shape in real life that started as a guest-curated page?

JH— Well, I won't take any responsibility for the curation of the original page. That was all Hannah. My role there was just as a collaborator, to help bring this to life on Artsy, and to make sure as many people as possible saw it from our user base and to blast it as wide as we could.

I have had a chance to see it in person, and, I mean, the show is absolutely fantastic. When you see works that you've only seen online, there is this element of surprise, always. The scale can surprise you, the materiality can surprise you, the texture — the way things show up in person are just different from the way they show up online. And it was one of those full circle moments. I've engaged with the art world primarily from a digital-first perspective for my entire career, so whenever we're able to bring things into physical spaces, those are the projects that are beyond exciting.

At Artsy, we think really hard about how we can make people become a first time art collector. One of the things that we see over and over again in our conversations with new collectors is that oftentimes at the beginning, they don't really know where to start. They don't trust their own taste and perspectives. But what everybody can do is relate to a person or an experience, or trust a taste maker who they think is amazing. So that's why I think it's so important to bring in as many people like Hannah as we can to share their personal experiences through art and inspire others. I've never had a guest curated collection like this then turn into something physical. So yes, this is the first time something like that has happened.

HT— I also do want to give you more credit than you're giving yourself, because the show wouldn't have happened without you. And the way I remember it is that there were three options, and you were excited about the hair option. So, thank you for that.

JH— Of course. This was special. I love any time we can really curate from the heart.

Don't Touch My Hair will be on view at Hannah Traore Gallery until July 27, 2024.

Bolding’s attraction to gestures of chance and accident can be attributed to his close studies of the highest arena of 20th century German cultural wars, where deskilled conceptual painters like Jutta Koether and Charline von Heyl, closely associated with the underground art scenes of Cologne and Dusseldorf, vigorously attacked conservative representational regimes within the established art world and quickly ascended into stardom. The lyricism and collaborative impulse found in Casey’s paintings could be traced back to Milton Avery, whose fondness for unrestrained use of colors and expressionist figuration lifted the American tradition of abstraction out of obscurity and into European museums. But perhaps the most fascinating of all of Casey’s influences is the most lowbrow: his time spent working for his uncle’s faux finishing company that covers the plain walls of middle-class households in Colorado with Tuscan style decorative patterns.

When Bolding invited me to his solo exhibition, I went in with a reluctant curiosity, as I have been a fan of his practice for a while but remained wary of how art history tends to monumentalize white male painters and mercifully allows for their self-mythologization. After an hour, I came out of the meeting with a completely different understanding of Bolding’s position within the art world. He is candid without being contrarian and sincere without being pretentious, seemingly propelled by a tender attention to social relations and concerns that often fall outside the priorities of the New York gallery circuit.

Bolding professed that he never quite anticipated the level of success he would have today. Coming from a suburban town south of Denver where “very few people had the resources to make it out,” Bolding’s upbringing foreclosed art school as a possibility. “No, this is crazy,” was Bolding’s instinctive reaction when he heard for the first time how much art school would cost, “I am not going to enter my adult life with a huge amount of debt.” Though he admits to being “untrained in some ways,” Bolding still insists that he could never claim to be an outsider. Indeed, it is perhaps more accurate to say that Bolding is a self-taught artist who has been rapidly pulled into the inner circles of the art world after nearly a decade of receiving little curatorial attention. After a group exhibition at Mammoth in the summer of 2023, Bolding was selected by artist-turned-gallerists Ted Targett and Anna Eaves for another group show hosted at Shoot the Lobster in late 2023. Soon after, he was approached by dealer Polina Berlin for a studio visit and she offered his first solo show.

Upon graduating high school, Bolding threw himself into the graffiti and skateboarding scene in Colorado. Trains were his main target. Seduced by New York with its more robust graffiti scene, Bolding moved to Brooklyn in 2013. He made a living by working at a print shop in Williamsburg and freelancing for various mural projects. Developing his practice in his free time, Bolding would spray paint graffiti inside abandoned buildings, where he did not have to “fight for space or worry about trashing some pieces of New York history.” When I asked Bolding if he was thinking about the validation of art institutions, Bolding maintained that he just felt like he needed to paint, given his access. “I often ended up with a bunch of materials from my uncle that would otherwise go bad,” he says.

Bolding’s style is indebted to graffiti culture and his years spent painting economically, and it manifests clearly in his works. In some, traces of paint dripping down are visible and exposed, and textured surfaces give the impression that these paintings were just scraped off a wall. At the same time, Bolding tries to veer away from the literal and explicit communication of graffiti, instead choosing to convey a psychological landscape that is ambiguous and ambivalent. Haphazard torsos blend into the background, twisted, bent over, and charged with tensions. Faceless, out of focus figures recur and turn away from the gaze of the viewer. Rare cases of frontal figuration are troubled by their ominous double.

In Bolding’s paintings, I also sense a thin veneer of otherworldly time. The kitschy, rustic feeling of faux finish is transformed into a poetics of unpristine sedimentation that takes on a durational element. Working with photographs — sometimes of family members, and sometimes of random children on the streets of Lower East Side — that have a particular temporality, Bolding’s brushstroke transforms them into moments of disquietude and pleasure, evoking universal archetypes and sitting outside of time. Mulling over these appropriated images intensely, Bolding’s constantly applies layers of oil, acrylic, flashe, and plaster on his canvases and then strips, sands, and trims them away, with the intuitive conviction that the source of the image becomes all the more effectively clear in this process.

Bolding can be quite sentimental about the objects he has collected and the people he has encountered. Yet, he does not seek to glamorize — or celebrate, per the tradition of portraiture painting — everyday life; rather, he favors a guerilla and confrontational approach with the immediacy of lived experience. In one painting, Bolding grapples with the nature of remembrance, using an Ikea bedspread as a tactile site of information both condensed and lost. Working with a former lover that is now no longer present in his life, Bolding hung the comforter on the wall and put a sheet of plastic over it. Together, they painted directly on the plastic,and then ran across the room to transfer the paint from the plastic sheet onto the actual canvas. While the details of the event cannot be recounted from merely viewing the work, traces of the co-creation can still be felt. In fact, this is one of Bolding’s favorite ways to paint. “I like finding shortcuts,” he confesses “I want viewers to look at my painting and feel like they can do it too.”

Bolding is looking forward to keeping painting and working with galleries, but he also anticipates more time spent with graffiti friends on murals. That isn’t to say he does not care about the allures of art world glamor and commercial success; rather, these achievements allow him to focus on what he truly wants and needs to do. The afternoon when we met he was in a well-worn t-shirt with exposed seams, several holes, and spots of paint residue, a perfect witness to Bolding’s personal history as a devoted painter. That t-shirt felt partially illustrative of why Bolding enacts the desire to paint — to document his devotion to painting itself.

And it is in fact the very idea of abstract interrelational experiences that comes to mind when strolling through the exhibits within the three separate rooms of Villa Clea. The Ritsch Sisters seem to have approached the architecture and interior of Villa Clea with precise playfulness, as becomes evident in the first room of the exhibition. Against the backdrop of a minimalist sound installation featuring the sounds of birds from New York and Vienna combined with occasional piano notes, we see photographs mounted on curved aluminum plates, which engage in a respectful dialogue with the space and the spectators. These sculptural photographs seamlessly blend into the organic monomaterial construction, which largely consists of light curtains, mirrors and aluminum furniture. As they either face or turn away from the viewers, they create a captivating interplay of proximity and distance, resulting in a wonderful ambivalent experience between concentration and spatial dispersion.

The second room shows a video installation titled Sound of an Egg Peeling, a symbolically charged exploration of human interdependence and connection. German-speaking viewers will likely notice the phonetic similarity between the English eye and the German Ei (egg). Might this be a meditation on natality and the Ritsch Sisters’ shared fascination with the seeing eye? In any case, eggs scattered throughout the room (sourced from a neighboring farm) create an immersive encounter, especially when visitors start peeling one of those eggs themselves.

In the third and final room, we find ourselves standing in front of a bed over which the largest photo print of the exhibition looms, titled Full moon she thought. It shows a woman with half-open eyes gazing at us from a potential delirium. Or is she annoyed that we disturbed her in her private bedroom? Those who don't fall into the bed at this point can turn over and enjoy getting their hands on the publication Together Apart by the Ritsch Sisters, which was published last year.

Immersive and fluid

For Villa Clea, Matteo Corbellini has used the remains of an old body shop to build a new architecture made of clay and concrete, while Allina (Alessandra Pelizzari Corbellini) designed the puristic and clear interior. Together, they have created an immersive and fluid space where they live, offer art residencies and aesthetic experiences, in a community centered around contemporary art.