Stored

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

Kobayashi Maru touches upon climate change, toxic grind culture, and mass media, all through Hascoët’s personal experience. The first chamber in the three-room show centers on his earliest influences: vats of Listerine, recognizable through their iconic shapes alone, alongside PS1 controllers and CK One, that ubiquitous, idealistic unisex scent. Lemons shout out Edouard Manet and echo tennis balls, a nod to Hascoët’s pup and Perrotin’s unofficial mascot, Simone. Three sharks prove that Hascoët, and society at large, have conquered the fears fostered by films like Jaws. Collective maturity has taught us that sharks are critical to earth’s ecosystem.

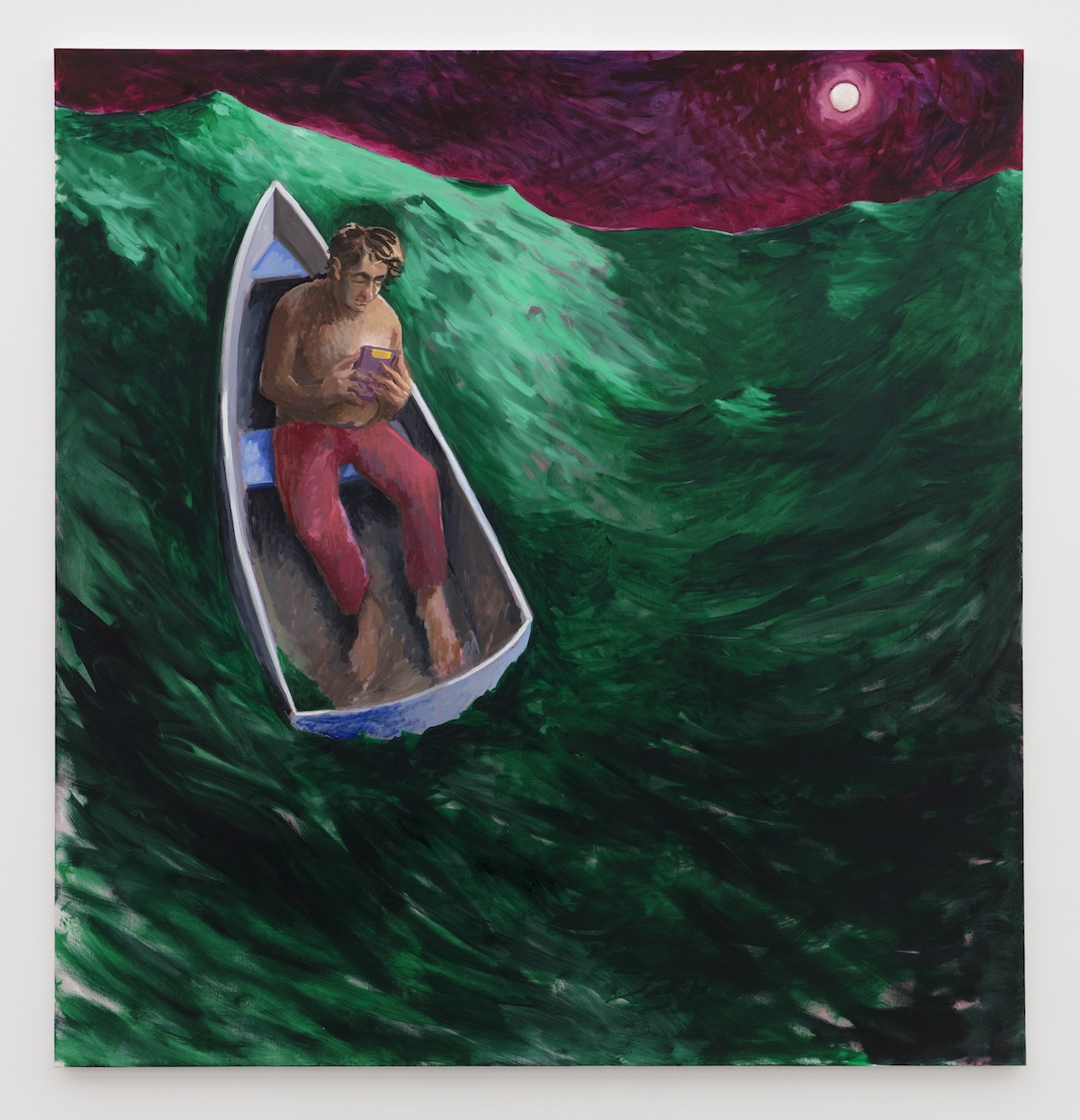

James T. Kirk, 2024

But Hascoët himself is the main character in the dream sequences that play out on larger canvases across the next two main rooms. In “The Waves,” Hascoët apathetically maneuvers raging seas in a dinghy, engrossed in his purple Gameboy. Those in the know will note he’s playing Pokemon, based on the yellow cartridge. Nearby, the show’s titular work depicts him sleepless, doom scrolling in a bed that straddles the tides and sands of a beach while a far off volcano erupts. The picture’s loose brushstrokes, underscored throughout by improbable pinks, contrast another self portrait across the way titled “Self Portrait with Brachiosaurus,” this time painted using a mirror rather than memory — with defined features and a rational color palette.

The real and imagined intertwine throughout. On walks to his studio, Hascoët discovered a store selling National Geographics for $1. Red pandas, dinosaurs, and polar bears have since entered his paintings, each bringing their own meaning. The advent of social media accounts attracting eyes with cute creatures has empowered red pandas to become the patron saint of a generation starved for joy. In “Red panda vortex,” this “kind of a new cat,” as Hascoët puts it, lounges in a magnolia tree inspired by springtime in Bushwick, on a branch jutting out over a water feature referencing Hiroshige. Elsewhere, Listerine makes one final appearance next to a red maple from his mother’s home, reimagined as a bonsai — or maybe it’s just a really big bottle of mouthwash. All depends on how you see it, much like the celestial bodies in “The Wave,” “Shiatsu,” and more resemble both the sun and moon. Hascoët’s not inclined to discern for you.

The Waves, 2024

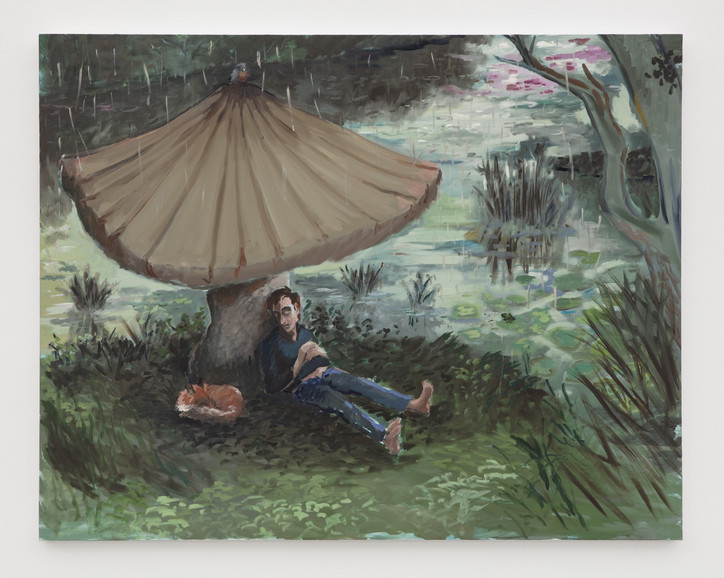

Shiatsu, 2024

Ambivalence and hauntology are the moment. As millennials have started entering their peak purchasing power and professional influence, 90s culture has proliferated contemporary art. It’s not a fad, but a mainstay — as emphasized by the art historical traditions Hascoët has translated such relics through, and rendered them alongside. He sympathizes with the desire for comfort in these uncertain times, but believes such motifs belie a deeper shift. “In the late 19th century, Nietzsche said ‘God is dead,’” the artist mused. “At the same time, Baudelaire came up with the idea that if God is dead, there is something to replace it. Why not poetry?”

Take it from both world wars — that didn’t work. “Then pop culture came along in the second part of the 20th century,” Hascoët said. “Poetry was quickly replaced.” Now, pop culture’s been used up. Rather than new stories, there’s a new Star Wars every six months. Kobayashi Maru doesn’t propose a solution, but honors Hascoët's diversions, like Polish-American techno DJ Bogdan Raczynski, who appears in a “Rave ‘Till You Cry” t-shirt. “I think it's a good way to implement poetry,” Hascoët remarked. “He would rip your mind open and then pour in some nice tunes.”

Cottage-core, 2024

Memes appear too. “Cottage-core” depicts Hascoët in his take on the “stop glamorizing the grind” meme. In the same room, Hascoët ponders his orb, right by another luminous scene based on the time Hascoët took Simone to a witch in Brittany to help her recover from getting spayed.

In fact, Hascoët’s grandmother was one of those witches, but when his father and uncle chose practical paths, the intergenerational chain shattered. Hascoët’s picked it back up again — and not without perfunctory tribulations. He failed at his first attempt to get into the École des Beaux-Arts, and heeded his father’s recommendation to try law school. Hascoët dropped out after two years, enraging his dad, then got into the École des Beaux-Arts courtesy of his renewed vigor for painting. Kobayashi Maru commemorates a decade since his graduation.

Hascoët believes the personal branding that characterizes Instagram and TikTok means the self will perhaps become society’s new god. His work has seized on that idea too, whether he wholly realizes it or not. While alchemizing disparate inputs like magazines, photos from friends, and his own observations, Hascoët only lets a painting leave his studio if he feels like it has soul. Interestingly, he says that without an element of self-portraiture that has nothing to do with the imagery itself, an artwork reads as vain. Even though he doesn’t appear in “Paleo-core,” the last work he made for this show, Hascoët sees himself in it. Whether he’s the T-Rex pissed off about the end of the world, the worried Brachiosaurus — or both — he still hasn’t decided. It’s up to you.

office caught up with Bois just after the new pieces dropped to dissect her brain, discuss what defines “art,” and dive into her latest menu offerings.

What first got you interested in creating things through a surrealist lens?

I was a big Tumblr teenager. I'm also an only child and I always loved to do crafty activities as a kid. I was always very drawn to nature and the long, repetitive task of assembling things and working with found objects or everyday things around the house. So I always say that my process today is a big extension of what I loved to do as a kid. I think that's where the essence of playfulness in my work comes from. I've always been really drawn to these kinds of mood board-style images — the best way I find to describe them is that they’re so visually appealing that you want to eat them. That's how I know that a photo is in a good place to be posted or shared.

There's that aesthetic appeal within your work but I also think there's a curiosity that comes along with it. As you said, that's very related to being a child and being curious and imaginative about all the things around you. When you were growing up, did you have an imaginary friend?

I had many imaginary friends in the form of physical things. I didn't have this ghostlike figure that only I could see and talk to. But I was convinced that my toys and stuffed animals had emotions and were coming alive when I was sleeping. Very much like Toy Story. I would put them in big lines and put the horses at the front and then let them lead the way. I felt this very close bond with inanimate objects that weren't so inanimate in my mind. I feel like that's still very much present in my work and my relationship with objects as an adult, being a big collector of ceramic dishes and found objects at the thrift store. I'm very drawn to the visual quality of objects.

When I was younger, I also loved spending time at the grocery store and fruit and vegetable markets. Any place where things are neatly organized, even at the hardware store. So to this day, I think that informed a lot of the subjects of my work. A few years ago, I think in 2018, I created this photo of a snow cone filled with dirty snow. To me, as a kid, that was always such an intrusive thought of wanting to eat the dirty snow because it looked like cookies and cream ice cream. So now as an adult, this is my visual representation of that. But I feel that there are so many subconscious references from my childhood that are very present in my work all the time.

Tell me about the meaning behind your ready-to-wear capsule name, Canapés. Why do you choose to produce slowly and how do you balance creating freely with creating ethically?

My ready-to-wear has been a passion project that has taken some time to be ideated and produced. I've been used to, for now, eight years, producing at a really fast pace. And I always say that my Instagram is kind of an exploration of the creative muscle — keeping it going and then moving on to the next post after. This was something that allowed me to really move at a slower pace and be more intentional — this also gave me more time to be a perfectionist, which can be a double-edged sword. But I'm very happy with the way this turned out. The name refers to finger foods. I love the aesthetics of finger food, for one. I love that they are always more presentation than taste. So that's very much what I wanted to portray: wearables that are all about aesthetics. I'm not necessarily trying to bridge that gap between function and the visual aspect, but creating pieces that are more about visuals than about function.

We've only done two drops, but they've been food-focused and it's a subject that I never get tired of. But because it is a personal project, I kind of want to just leave room for it to be whatever. I want it to be my own playground. In terms of the production process, we produced the bags in Italy and Portugal. And then we worked with someone to assemble all of those parts because the facades of both the shoes and the purse are silicone and PVC made. And then in terms of the quantities, especially today, it would be very crazy for me to say that anyone needs any of these products.

So I think this is an homage to the objects, but it's by no means something that has a place to be mass-produced and consumed in high volumes. I think the beauty of it is that it is in small quantities. It's something that's just a special thing to look at or to own or to wear. And just like my other work, I like it to serve many functions and to be adaptable.

I think for people who have been following along with your work, that's the intention that you set with your visual work and the digital renderings anyway. There's such a focus on the artistic aspects of what you're creating that I think it set the tone for the ready-to-wear pieces. A lot of fashion lately is not about fashion as an art, but I think seeing these pieces that are so intentionally created shows a different perspective of what fashion can be. Why do you choose to use everyday, mundane objects in your work?

I think it's a matter of relatability for me. It's more fun to subvert something when you know that most people have the reference. I find there's more power in it than if you're just doing something for yourself. I understand doing something for yourself and being the only one to get it. And sometimes I do like to have those Easter eggs in there for my own sake. But the bottom line is that whatever I am into and what I find visually appealing at the time, will most likely be included as a subject. I'm based in Montreal and we have four super distinct seasons, so I'll get very inspired by seasonal fashion, seasonal foods, and things like that. So whatever is in my lens at a certain moment is probably what's going to end up being featured. And like I said before, I still find a lot of enjoyment in places like grocery stores and hardware stores so that's where a lot of 'aha moments' happen.

You could totally make it feel like people are stepping into some of the photos you've made or getting to live within your pieces. For this new drop, I know there were some intentional choices behind using the clementine as a symbol and the feelings that that motif brings about. How do you want the collection to make people feel when they wear it?

To me, the clementine symbolizes luck. And then the orange and the citrus, in general, can be so fresh and optimistic. Just like the images, I love it when my work is digested at people's pace and when people bring on their own interpretation of it. There's no real way that I hope that it's taken or that I wish people would take it. I think it's just a very visually interesting lucky charm.

I totally agree that all of your pieces, and with any art, it's all up for interpretation. I know we touched a little bit on the silicone, PVC, and certain materials employed in this collection. The last drop blended artistry with some quite advanced technology. Were there any fun, unexpected processes or techniques used to create the Clementine collection?

Something important to me was to model the actual replicas of the clementine from the real fruit. So we used actual 3D scans of specifically chosen clementines and that made it feel real. I made this very DIY model of it about three years ago in my old apartment and sent it to my manager back then and said 'Oh, I really wanna do this.' And it's funny because we released Rhubarb first, but Clementine was the first idea that started the whole wearable line idea. So it all stemmed from that. Now I'm lucky to be able to bring my ideas to life in that capacity.

Do you think anything can be art?

Absolutely. I very much agree that beauty is subjective and all that good stuff. But I am also super opinionated about what I think is good art or bad art. That's why I'm also very receptive to people not liking my work and not thinking what I do is art. I don't have any issue with that. I appreciate that it's just a playground for everyone to be able to be like, 'Oh, I really hate that,' or 'Oh, I really love that.' And neither answer is the end of the world and nobody needs to be right. It's more of an open-ended thing and some things that I didn't like years ago, I can love today. Art is fluid and it's evolving, so I'm not too involved or bothered in any way by the fine art world or the emerging art world. I go to openings when I'm invited. If I'm drawn to it, I go watch movies that I want to watch and all of that can be sources of inspiration. I'm very curious.

These two drops that we've seen so far have given people a taste of the wider Gab Bois universe. What's next on the menu?

With the wearable pieces, I want to aim to drop two drops per year. We're aiming for the next one in November of 2024. I want to create my first jacket with that drop. I also want to put out some more entry-level collectible items just to allow the work to live outside of the digital realm and for people to have a different sensory experience with it.

There's something really unique about the artistic ability to be able to see something that's super commonplace and think of the possibilities of what it could be. But I imagine that there are certain ideas that you render or conceptualize that may be very difficult or not possible to bring to life at all. What, in your mind, distinguishes an idea that remains a hypothetical creative concept and an idea that becomes reality?

Sometimes I can't explain what drives that, but I would say that it really comes down to doing it versus not doing it. That truly is what it is. There's a driving force that makes you take the next step versus not. I have a team here now and we like to brainstorm all together and we usually narrow down, maybe twice, the amount of ideas that we end up creating. I guess it's just a matter of what I picture in my mind. Timing is super interesting in that way where I'm now revisiting ideas that I put aside years ago because I didn't think they were strong enough then. And now I'm like, 'Oh, this is great.' Ideas and inspiration move in such abstract ways. Even with other people — I'll have this idea, put it to rest for a minute, and then someone else will do it. And that's great because it just came out through a different channel. So I like to keep my mind open for ideas to come in and out. But there are quite a bit of the ideas that we bring to life, for example, for photo, that we produce and we shoot and then it doesn't work. And we just have to accept that that's okay too.

There's a learning experience in that trial and error, I'm sure.

Definitely. And that's something that, in the beginning, I was so attached to — the ideas. I was fighting it and I would redo things like 10 times and just get so frustrated, whereas now, I'm in a very privileged position to be able to just let go of some ideas and not have to produce every single one of them. It's a much more comfortable place to be in.

Are you a perfectionist in your work?

No. I wouldn't say that. I am particular, but I wouldn't say that I'm a perfectionist. Obviously, speaking of my personal work in terms of commissions, I have to be. But if it's something I'm making in another context, I don't need it to be perfect. Ever.

I think it's an unlearning process, especially in art, to teach yourself that there are still lessons or beautiful things to find in imperfections. Have you ever read the book Big Magic?

Yes, I have.

That's exactly what I thought of when you were talking about ideas. And how you're just a channel that they pass through and if you don't grab onto an idea and actualize it, then it could float away to someone else.

Oh my god, I love that book a lot. I've recommended it to a lot of people and I find that a lot of people have a barrier to entry to self-help. But I react very well to that. I'd be a great cult follower [laughs].

Your works take on a really trippy, imaginative quality, blurring the lines between fantasy and reality. What does your ultimate fantasy world look like — who’s there and what do you feel when you’re there?

Well, one disclaimer is that my dream world for myself is not the same as the dream world I'd offer up to others. My home is all gray tone, stainless steel. But it relaxes my eyes a lot whereas in my work, I tend to be more on the maximalist side. A lifelong dream of mine is to design a themed hotel where you can really check all the boxes from the hospitality standpoint to restoration and just tap into all the senses. I'd love to enhance that visual experience, the sleep experience, the eating, and just create a surreal sensory overload. This is a dream that would encapsulate all of the fields that I hope to one day be able to tap into with my work.

How is The Grumpy Girls a departure from your previous shows?

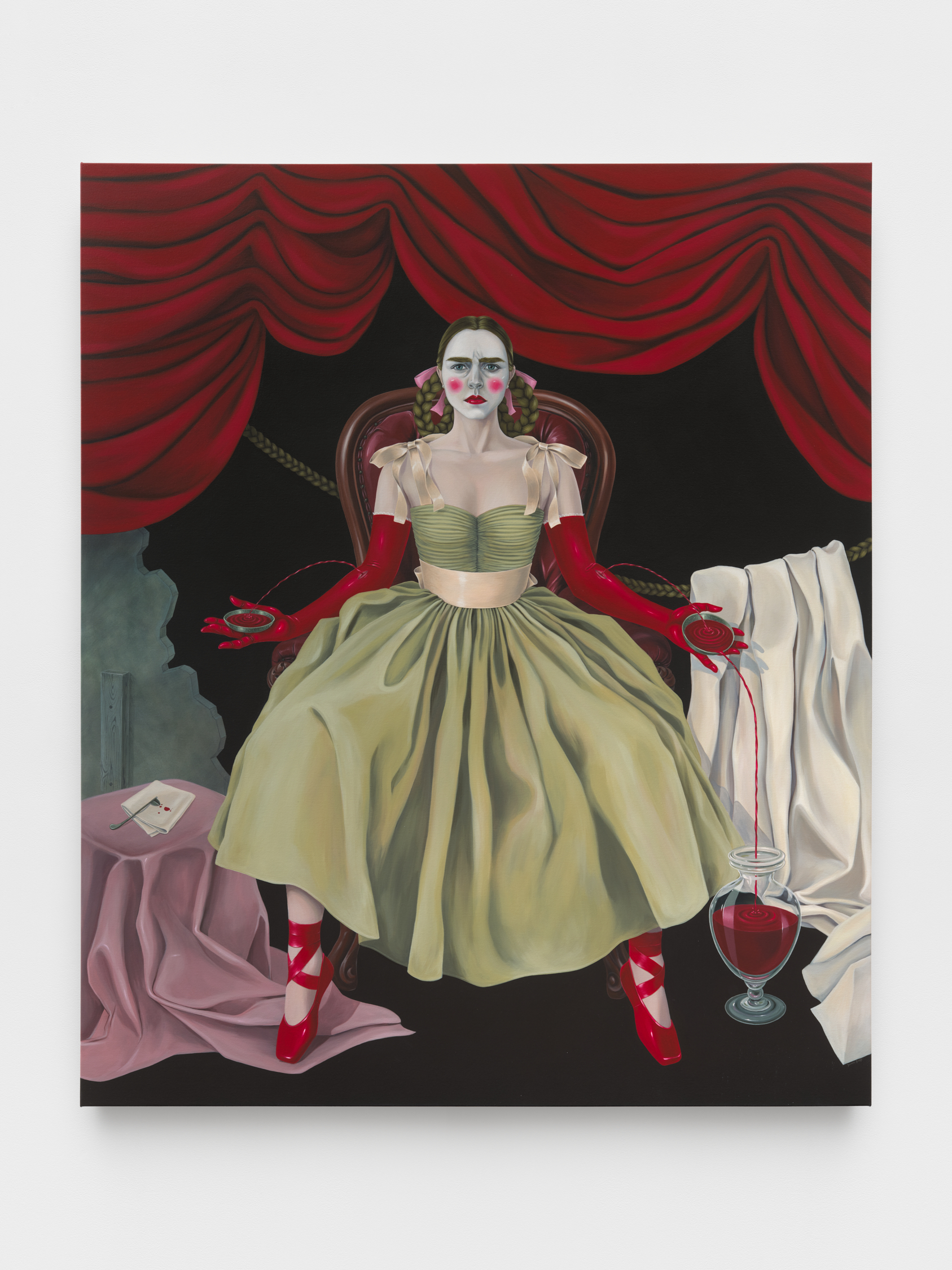

My last show was really a linear narrative and The Grumpy Girls is a bit more of an abstract narration. There’s not a clear beginning or a conclusion to the story. It’s giving you the different pieces and you can arrange it in whatever way speaks to you.

It’s a bit of a technical challenge for me. I had never worked with multiple figures this way before, especially in the large works. I would say it’s an evolution [of my previous shows] I’ve been working conceptually with the same ideas… motherhood, sacrifice; this before and after of motherhood.

It seemed very crucial for the girls to be grumpy. Why is it important for the grumpiness?

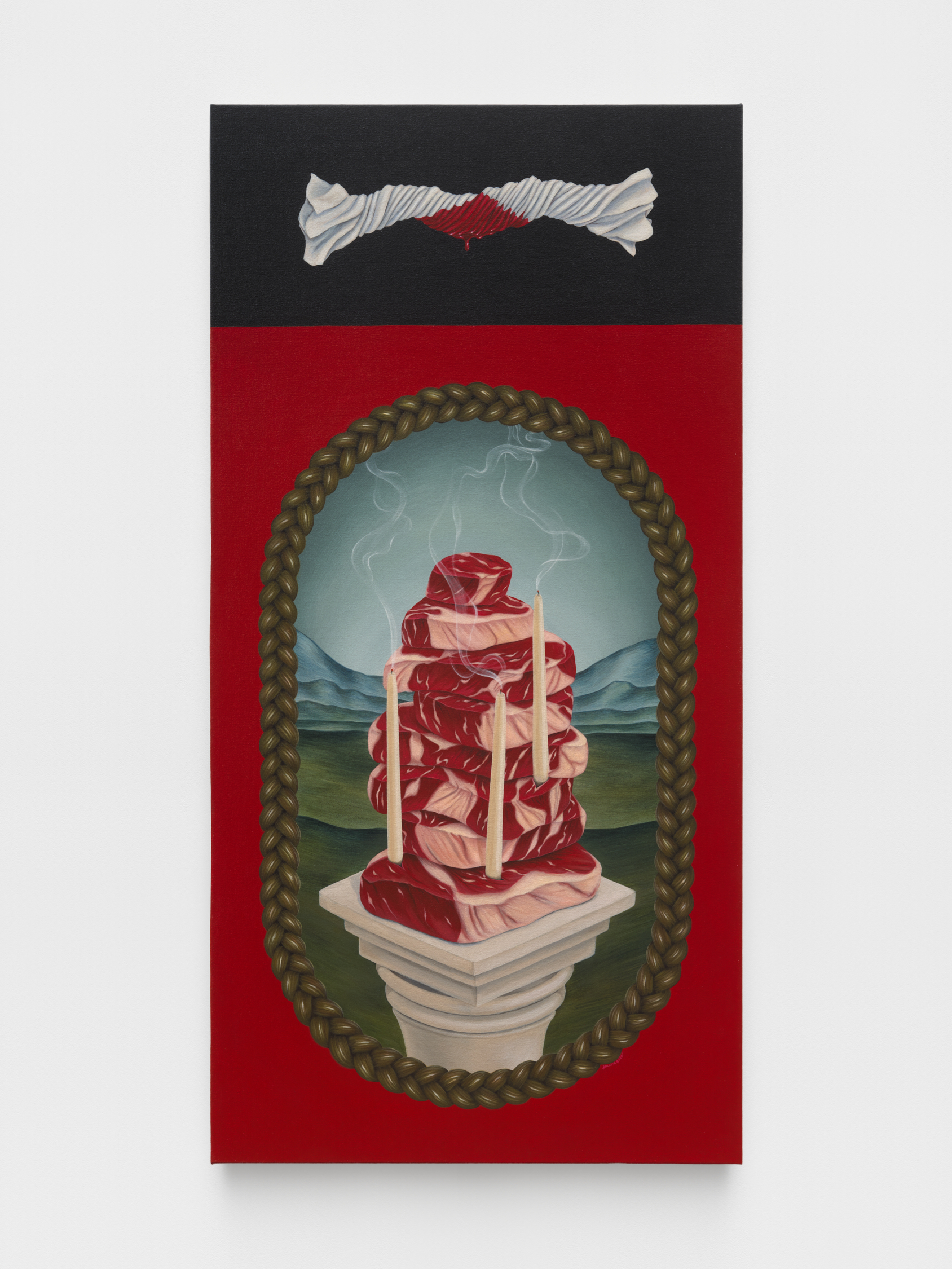

It takes this very serious idea and winks at you a little bit. I like this idea that they’re doing this labor, they’re braiding this hair or preparing the scenes, but they’re not thrilled about it. There’s reticence, they’re begrudgingly doing this work in service of the play, the film, however you see it.

Having them openly frowning is important for that to convey their unwilling participation. And also frowns are very fun to paint. It’s fun to paint these frown lines. More traditionally in representation of women in painting, we don’t really see a lot of anguished, frowning faces — that’s more rare.

What was the creative process?

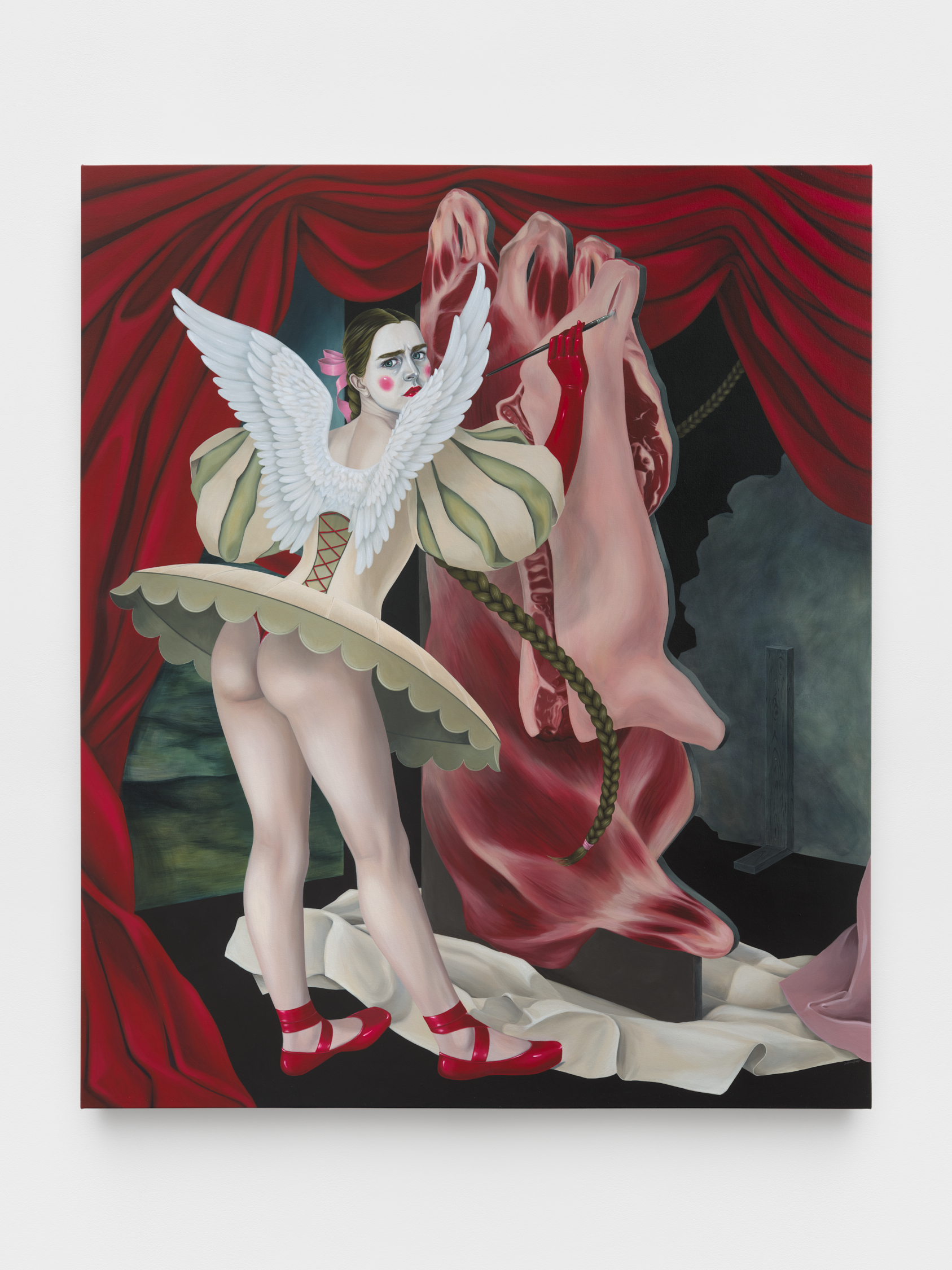

It started with a sketch that I made in the summer. The sketch became the artist, the winged figure and she was initially facing the viewer and looking very stern, very grumpy. And I like this defiant gaze. I kept developing that sketch and started building out these other iterations of that character, so the girl and the mother. And at some point, I realized they all had to come together. That’s when this fourth figure emerged, this nude self that they’re all sort of working in service of and the rest of the show was about paintings that would support the storytelling of these four works.

There’s a lot of technicolor theater and costuming references. How did you choose those cross-references to come across in your work?

I really like that era of cinema. The Red Shoes is something I referenced in my last show as well and I continue to go back to. It’s such an interesting story and thematically it really aligns with this show in that it’s really about whether art making and a full life can be compatible, which is the question that I’m asking with this mother figure who's disrupting the braiding scene with the scissors. What are the elements I need to let go of to make space for this new identity? What things need to be sacrificed to be a mother? And what of those things need to be sacrificed to be an artist?

What conversation are you having with yourself through the paintings? Like presenting yourself as a visual artist and pulling back the curtain… what’s going on internally with that?

There’s a degree of vulnerability. But there’s still the veneer of guarding myself, I suppose. The nude figure is most representative of that — laying there like a beach siren nude, but she still has the [opera] gloves and is still wearing the makeup. It’s sort of me saying I allow myself to be vulnerable to a point in my work. And I think that’s where the camp, winking, tongue and cheek element plays in too, because I’m taking these very serious, heavy ideas — it’s adding something acidic to something very fatty.

Especially with these three archetypes, trying to interrogate different aspects of myself. The blood letting one especially is me unpacking my vanity and my relationship to beauty culture and beauty rituals. I’ve seen so many videos lately about simplifying your skincare routine and I used to be a 12-step [skincare] girlie and I honestly don’t know if it was helping. Historically, when you look at these really dangerous beauty practices like lead face paint, those women never knew they were hurting themselves at the time. While the other archetypes are a bit more reflective, the mother is hypothetical — I’m imagining a future version of myself.

It’s definitely portrayed that there’s this cost to girlhood or womanhood. What was it like to portray that cost?

That’s a perpetual tension in my work. The desire to paint a beautiful figure, but to also represent myself in a way that feels honest to me and navigating beauty ideals in painting and media more broadly. Having pubic hair in a painting, I heard from other artists that they were discouraged to have women’s body hair in paintings and then at the same time, my figures don’t have armpit hair or leg hair. I’m battling my own internalized ideas about beauty standards. As I make more work where I push myself to resist [beauty] ideals more, I notice I become more comfortable in my own body in my real life.

How has your previous experience in fashion contributed? I noticed the opera gloves in the pieces…

Costuming is very important to me. It’s very fun to paint dramatic folds and poofy skirts. The costuming can tell so much of the story for you too. The artist is the most free version of myself so she has these wings and this tiny little tutu that’s a contemporary version of a tutu and it shows her legs and her butt.

The gloves have been a barrier layer, there’s sensuality to the [opera] gloves, but actually whatever is being touched by the hand in the glove is not being touched by the hand itself. I like the sensuality of that restriction. I like to have these feminine elements in contrast to blood and meat, these more grotesque images.

What made you think Oh, I’m going to have this ballerina paint this meat carcass? What was the symbolism behind the carcass? Is it a meditation on femininity?

She’s painting a set piece. So the idea is maybe there’s a slaughterhouse scene that we’re not seeing. But also it’s a nod to my previous work where I’ve painted a lot of meat. She is the archetype that I identify with most at this moment. I like having her in this meta… her painting meat while I’m currently painting [her]. Meat in my work is a symbol for the body. Meat being decontextualized from a consumption context makes it feel a lot more fleshy. This metaphor of earthly flesh, decay, there’s an ephemerality to it — it’s fresh right now [the meat] but it won’t always be.

It’s pulling back the curtain while also showing the stage. How did you manage to capture both?

That’s the duality of these feminine touches and having them directly alongside bodily horror imagery. That it’s staged suggests there’s an artifice here. The surfaces are really smooth and they’re varnished with this fat and finish that gives them this weird quality that’s almost like you’re seeing it through a screen or a piece of glass. It’s a performance — an image that’s not totally solidified. There’s a degree of removal.

Out of all the things you could paint… what’s so interesting about self-portraiture to you?

During Covid, I was stuck at home and this is what I had to work with. It was also a way to project myself into fantasy settings and scenarios that weren’t accessible to me at the time because we were locked down. That’s the origin and now it’s really about trying to know myself, to be corny. I discovered so much about my wants and desires in making these paintings. The things that I’m unpacking or saying at the outset of a body of work develop and surprise me by the time I finish it.