Stored

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

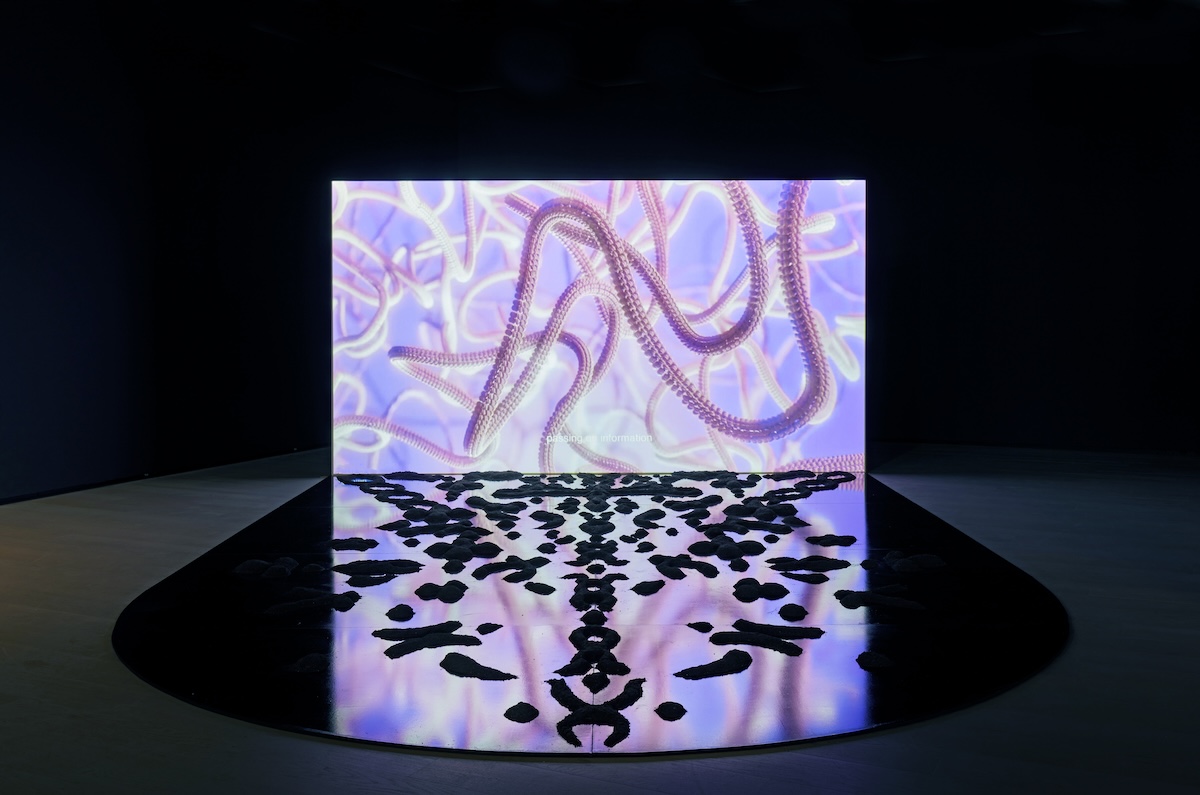

Lena-Kuzmich CHIMERA, 2022, animation film and installation 9:30min.

The film has inspired many artists since its release nearly sixty years ago, and is currently serving as the basis for a new group exhibition, Sacro è, at the Fondazione Merz in Turin. Curated by Giulia Turconi and featuring work by artists Tiphaine Calmettes, Matilde Cassani, Giuseppe Di Liberto, Lena Kuzmich, Quỳnh Lâm, Tommy Malekoff, Lorenzo Montinaro, and GianMarco Porru, the show investigates the concept of sacredness as found in everyday things. Like Stamp’s character, the exhibiting artists seek to expose the potential for transformation and spiritual reinvention within the quotidian, and achieve this through works spanning performance, installation, sculpture, painting, and video.

Giuseppe Di Liberto, Ghirlanda, 2020. Courtesy the artist.

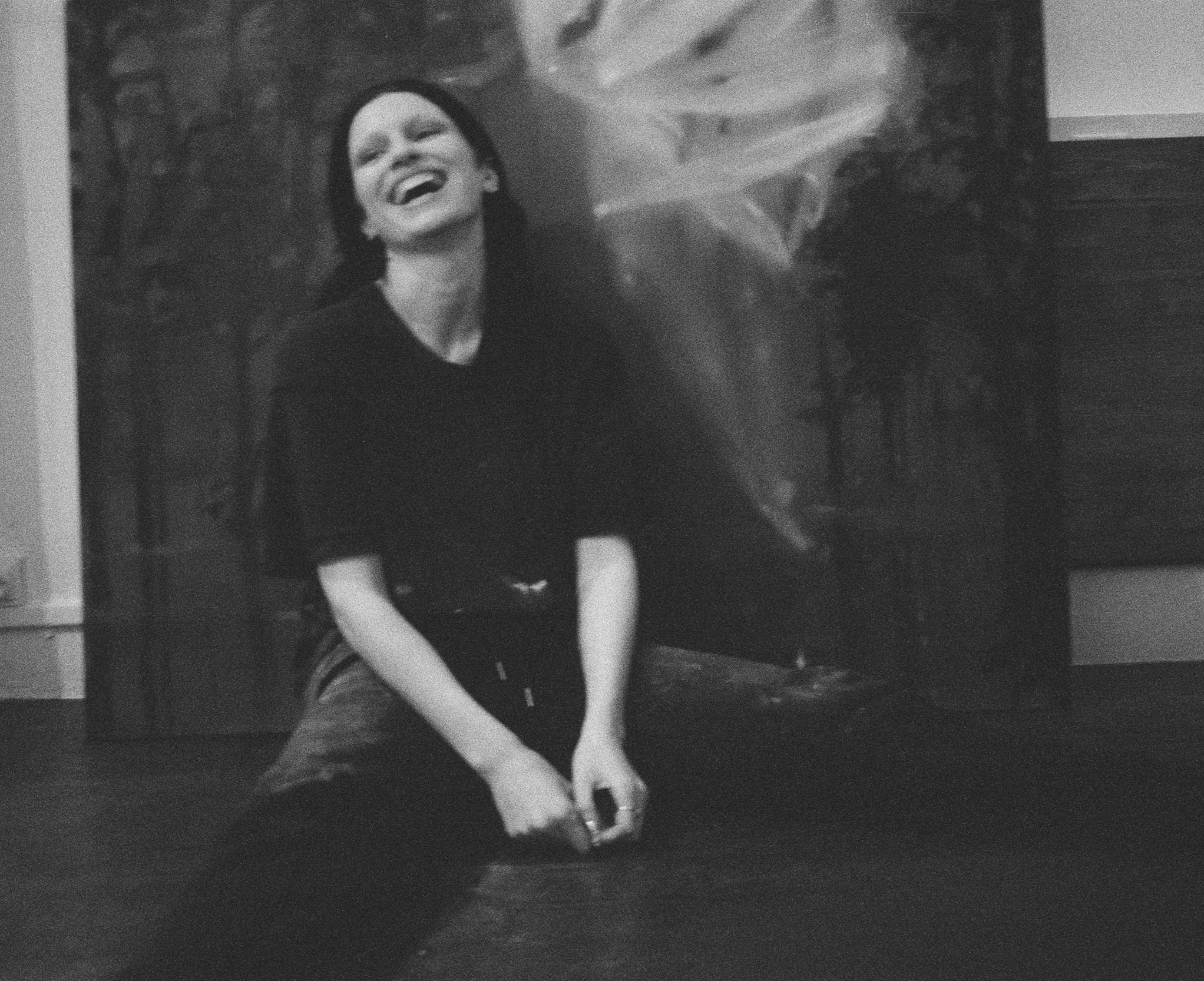

The exhibition’s opening coincided with a live performance by the artist Giuseppe Di Liberto on the evening of March 18th, 2024. The production, Sparge la morte (2022), was originally performed by Di Liberto and his brother Davide two years ago, and features music by the madrigal composer Carl Gesualdo. Inspired by a walk the brothers took in a cemetery in Naples, the piece’s choreography mimics the traditional death ritual of sin eating. Popular in border regions in the 18th and 19th centuries, sin eating involved the ceremonial eating and drinking in the presence of a corpse, and was believed to absolve the deceased of their wrongdoings.

The performance immediately set the tone for the rest of the exhibition with its stark portrayal of the extremes of life and death, ascension and degradation. As Gesualdo’s score resounded from behind a curtain, the brothers stalked up and down the Fondazione Merz’s spacious front room, retracing their steps in an obsessive trance and glancing out at the viewers as though from beyond the grave. Here, the fraternal aspect added an even more ominous edge to the already dark happenings: at times, it seemed that each brother might overcome the other entirely — and the audience as well. When the performance was over, the two hugged; still, a suggestion of danger and the possibility for a potential devouring lingered in the air.

Tiphaine Calmettes Hutte à mains, 2022. Photo Pierre Antoine.

Tiphaine Calmettes Ménhir à alcôve, 2022. Photo Pierre Antoine.

Echoing the themes of consumption and imbibing present in Di Liberto’s work, the French artist Tiphaine Calmettes presents Primordial Soup (2022), a clay and earth sculpture that doubles as a cauldron. Inside the cauldron is a vat of hot, blood-colored soup available for spectators to sample. In an exhibit inspired by a film that was condemned by the Vatican and led its director to be charged with indecency (Pasolini was eventually acquitted), it is the most overtly sexual work: its materials pass directly from the artist to the lips and into organs of the spectator. If this erotic transfer were not enough, the cauldron resembles a Venus figurine, with exteriorally-hung ladles that call to mind pendulous breasts.

Tommy Malekoff Desire Lines, 2019. Two channel digital video and sound 15:42 min. Courtesy of the artist.

In a separate room, a video work by New-York based, American artist Tommy Malekoff, Desire Lines (2019), plays on an endless loop. Filmed across fourteen states between August 2017 and March 2019 on a handheld camcorder, the fifteen-minute film is described as an “ode to the surreal potential of parking lots across America”, and focuses solely on the aforementioned liminal space. A kind of reimagining of the famed John Cheever story “The Swimmer” (1964), in which a probably deranged man decides to swim home only through his neighbors’ backyard pools, Desire Lines criss-crosses the U.S. by means of a different, but similarly common landscape.

In the film, we witness a variety of scenarios play out across multiple parking lots, including but not limited to: a firework display set off by shirtless teenage boys, a herd of iguanas passing idly through, a prayer circle that release a rosary of balloons, a military drill in full action, a woman dressed as the Statue of Liberty juggling batons, a beer drinking competition, kids arriving by horse at a Sioux Nation shopping center, and a solo dancer using a cardboard box as his makeshift stage. Like Pasolini, Malekoff trains his lens on the banal, finding there an explosion of previously untapped potential and people desperately waiting to be seen.

Lena-Kuzmich CHIMERA, 2022, animation film and installation 9:30min. Sound Design by Leonard Prochazka. Graphic Design by Winona Hudcová

Despite the excellence of the work by Di Liberto, Calmettes, Malekoff, and the other artists, it was the Austrian Lena Kuzmich who best surmised the central themes of Sacro è. In their video installation, Chimera (2022), Kuzmich examines queer ecology and nonbinary life within nature, questioning what defines humans as a species. As the video came to a close, bold, all capitalized letters flashed across a screen in the Fondazione Merz’s basement: LIVE LOVE FUCK DECAY TRANSCEND. Pasolini, one imagines, might just approve.

Sacro è, is open at the Fondazione Merz in Turin, Italy from the 18th of March to the 16th of June, 2024. Pasolini’s film Teorema (1968) will be screened in accordance with the exhibition in the Fondazione’s cinema room on the 23rd of March, the 18th of May and the 8th of June at 4pm, the 10th of April, the 8th of May and the 29th May at 5pm, and the 21st of April and the 16th of June at 11.30am.

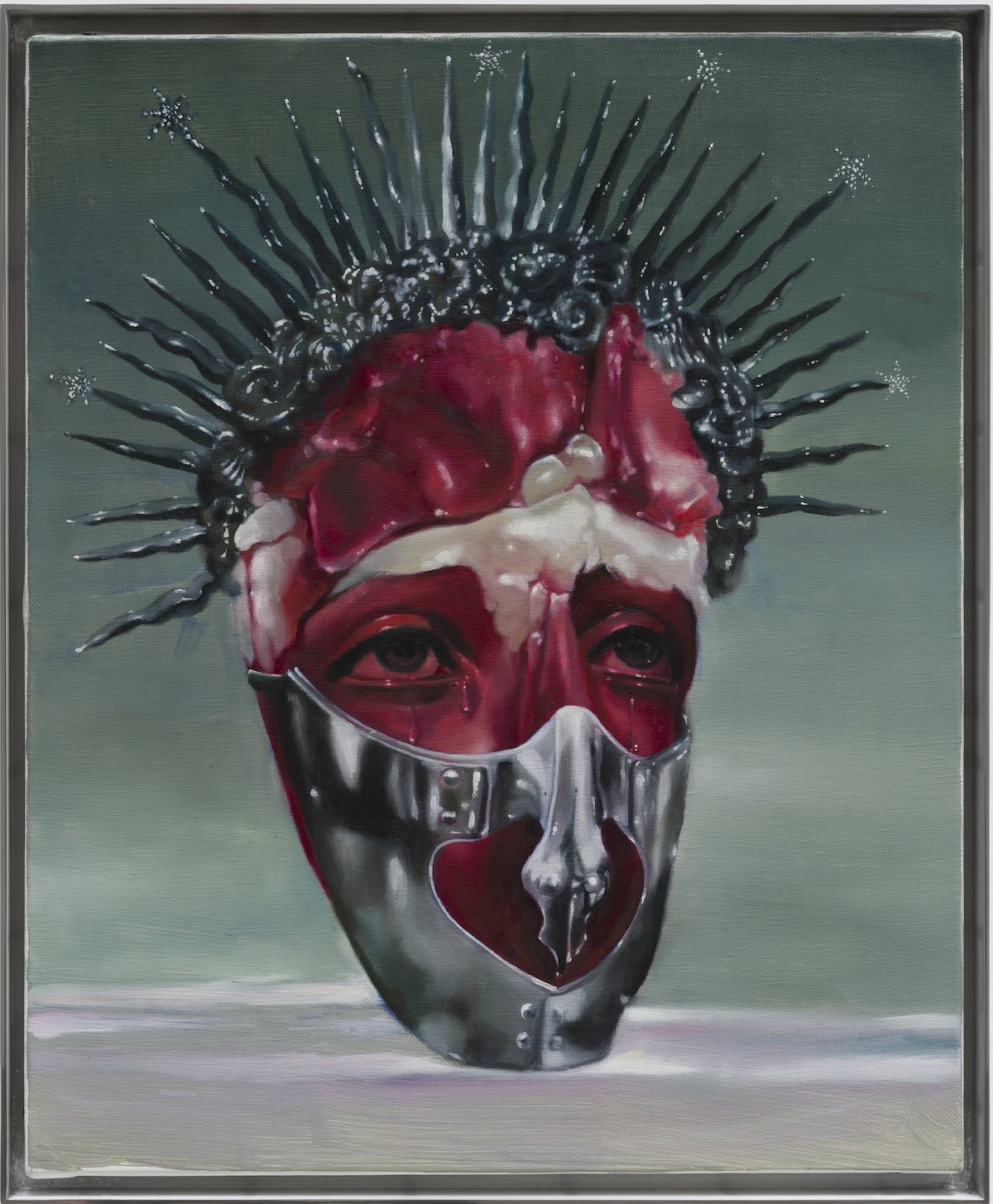

Belladonna, 2023

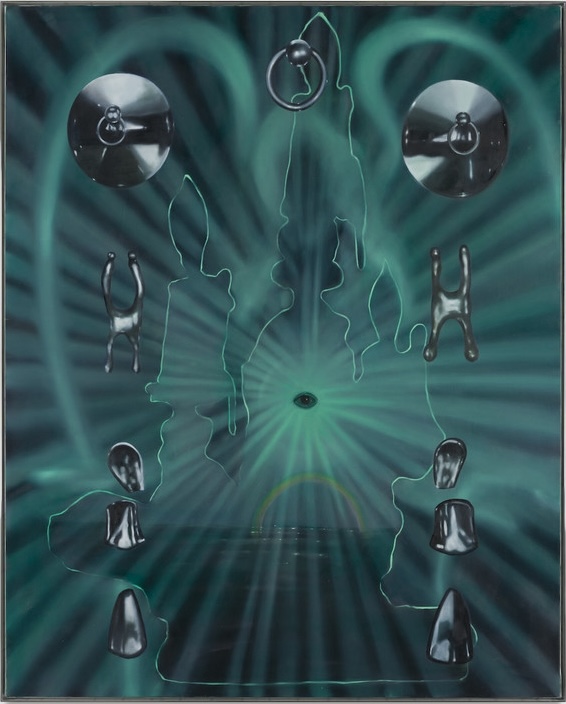

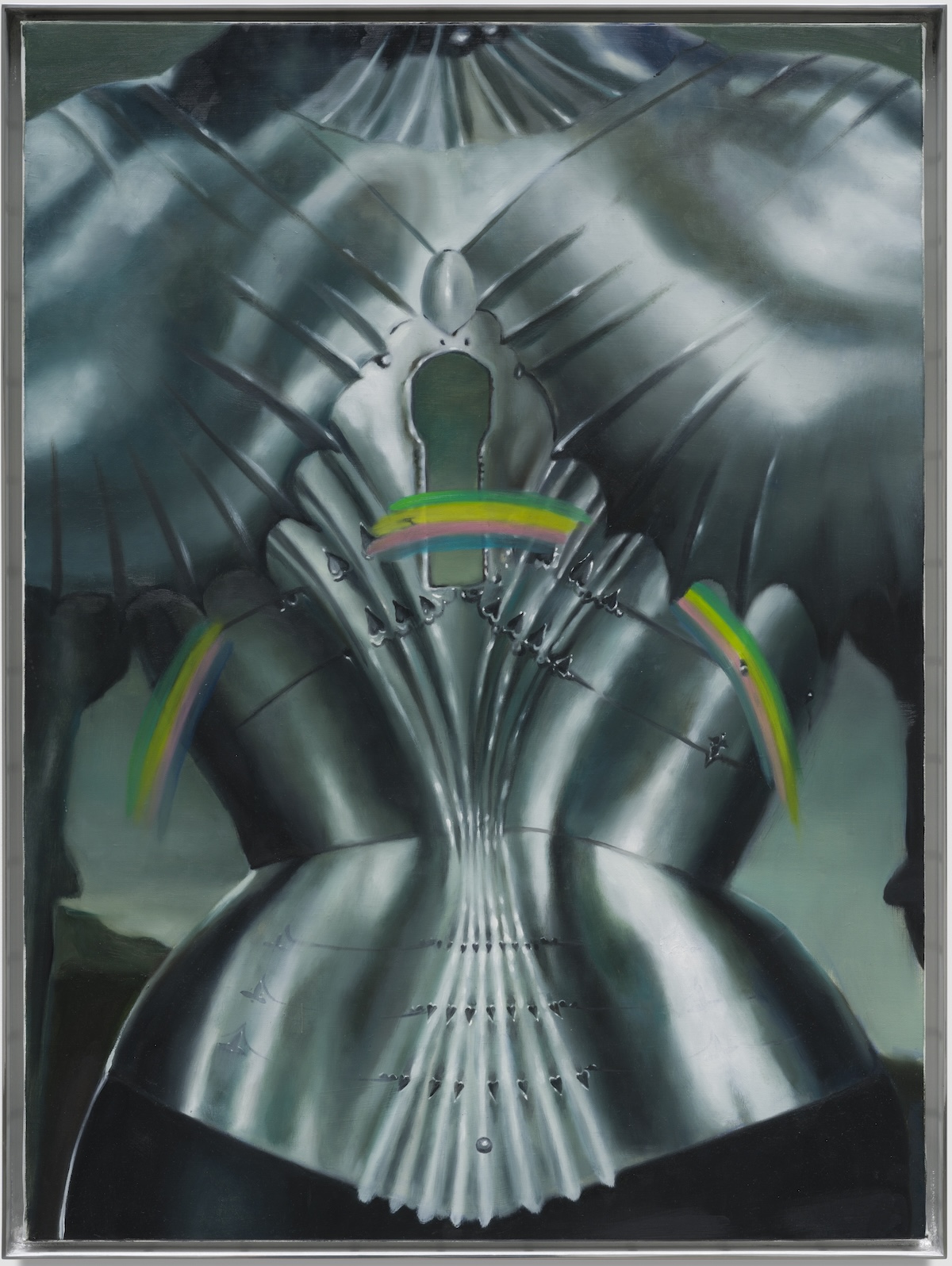

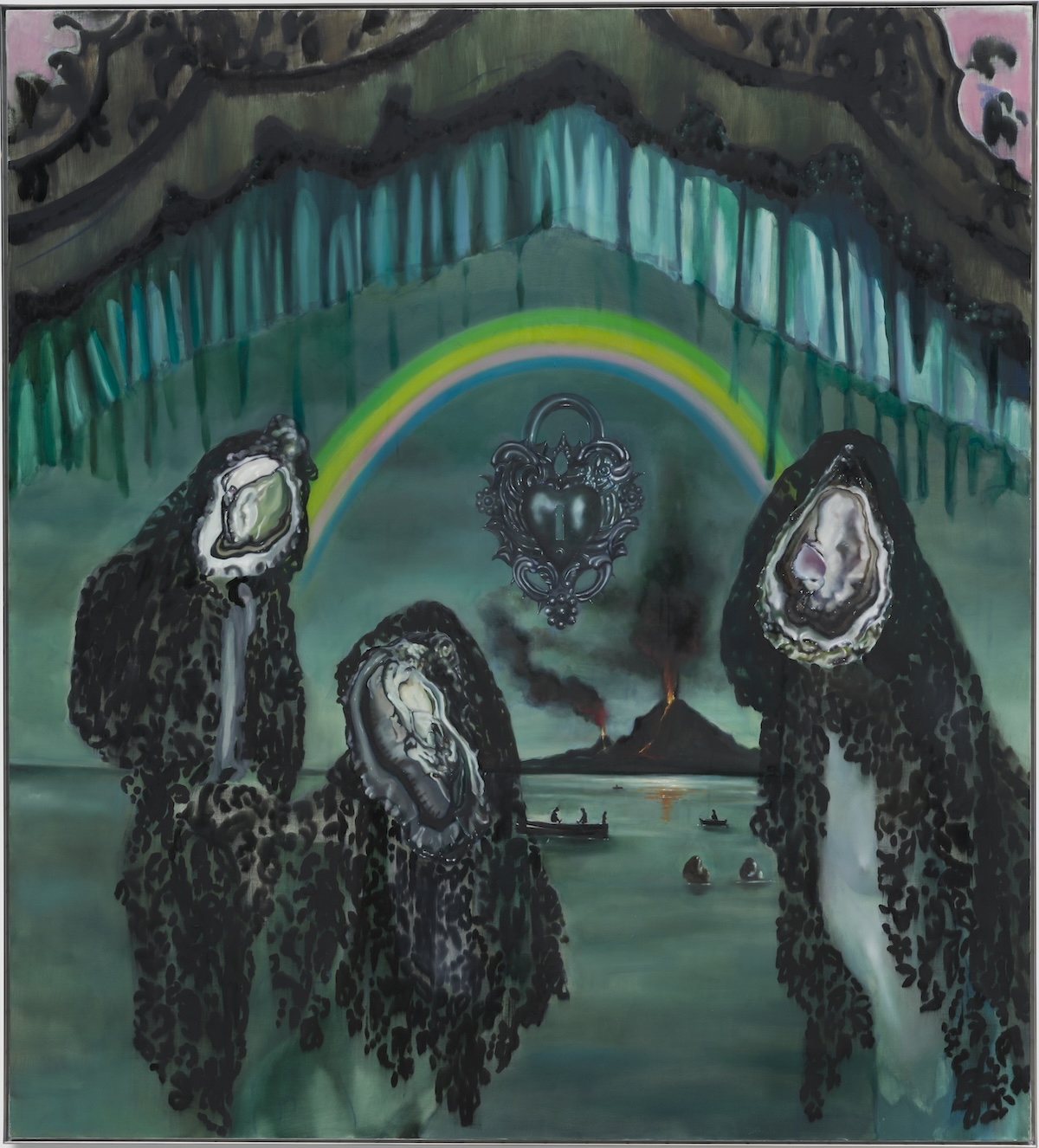

The results are just as vivid as her psychic landscape. Rendered in oil on canvas, her latest series merges mythological and folkloric references with Lennox’s own symbolic lexicon. There are shells and shrouded figures; bodies of water and gleaming oysters; crying eyes and rays of light. Women’s bodies appear in a state somewhere between pain and pleasure, tension and release, orgasm and apocalypse. Evoking the beauty and savagery of the natural world, Lennox probes our contemporary ennui and enduring fascination with the end times—finding solace in the idea of nature as the highest power, and surrendering to its cycles of creation and destruction. Currently on view at Nicodim Gallery in Los Angeles for her latest solo exhibition, Tremors, the paintings invite viewers to join Lennox in the space between. After all, Lennox says, “Life is but a dream."

Themes of apocalypse and end times are very front of mind these days. What do you see as the role of art in helping people process this?

I believe that painting has the power to open up pockets within us where we can access the things we’re fearful of. The show’s title, Tremors, is referencing this sort of secret fear within me, which I think everyone can relate to right now. We are in a time of general unease; there’s this sense of potential disaster or oncoming decline. I started contemplating what it means to tune into that powerlessness and the feeling of surrender. From there, I started thinking about the bigger picture: contemplating the history of the universe and the fact that the world has always had such dramatic huge cycles of change beyond what I can even comprehend.

For the past two years, my boyfriend and I have gone to sleep listening to a series called The Fall of Civilizations, which is about different empires from the past and how they fell. When you start thinking about that scope of time, you realize that above and beyond our experiences, nature has always been the puppeteer. When you also bring the element of magic or fantasy into the equation, it leads you back to the notion that life is but a dream. At the end of the day, if there have been civilizations that have lasted for centuries and centuries, and then suddenly they’re just gone, what was it to begin with?

Within the show, I’ve tried to express the tension between the minutiae of internal experiences and the expansion of the external—[finding the] fusion of that within nature. The metamorphosis of nature, the power of nature overcoming humans, this dual savagery or beauty that nature holds, and the question of, Is this a utopia or an apocalypse?

Mythology is central to the series. Where did you draw inspiration from existing folkloric legends, and which symbols and motifs arose from your own experiences in the world?

At one point, I was in Greece and I was going to quite a few caves. Some of the most profound, mesmerizing experiences I’ve ever had have been in caves and cenotes. It’s this primal feeling; it’s womb-like, it’s elemental, it’s ancient.

I love this notion of the great return, and I symbolize it with shells, with water, with oysters—which, of course, could be interpreted as female anatomy. It’s like the birth of Aphrodite; it reminds one of coming back to the ocean, to water, to the womb.

Tell me about the books or historical sources that inspired your approach.

There’s this very large, very old book from 16th-century Germany called the Augsburg Book of Miracles. It’s full of gouache paintings of very surreal apocalyptic scenes. There are comets, there are swarms of locusts, there are strange mythological creatures, there are images where it’s raining flesh and blood, there are rainbows. It just has this sense of mysticism, wonderment, and total unease. Nobody knows who made the book—it’s a mystery.

I also read a book called Medieval Bodies, and learned that in the middle ages, there were a lot of interesting parallels being drawn between human body parts and parts of nature. The lungs are like the wings of a bird, symbolizing flight, breathing, movement, and life force. The nervous system and the brain are like tree roots. It goes back to this kind of external, internal relationship between nature and the human body. So I think that’s also where I got a lot of these motifs of shells and barnacles and metamorphosis.

How much are you consciously crafting these layers of meaning, and how much of the work is free-associative?

I’ve never wanted to create paintings that make people feel one singular thing. I think it’s fascinating to let people go on their internal journeys with what these symbols might portray for them. There is a meaning behind everything I do, so there are lots of little doorways to open if one pleases. It’s like a secret within a secret.

For example, Touching the Vessel, that painting with the silver metalwork, is a reference to Betony Vernon’s jewel tools. To me, the work she does is like a metaphor: she’s making these beautiful objects that allow people to erupt in a sense, to open, to break through. These objects are like a symbol of physical transcendence. So they were a metaphor for orgasm and out-of-body experience. And I love that the same motif that conveys disaster and chaos can also be a symbol of pleasure and transcendence.

I’m curious about your own experiences—have you had any out-of-body experiences, or experiences that completely shifted your perception of the world?

Through methods of alternative healing, I have had experiences that made me feel that my sense of reality, my sense of existence in the world, was turned inside out. I’ve had these moments come not just from beauty but from pain. Again, it’s like life cycles: You get these breakages in nature, these massive ruptures, and after that, something transforms. Before the butterfly comes out of the chrysalis, a caterpillar has to turn into goo.

We can’t live in a state of eruption or transcendence all the time; it’s always going to be temporary. But human beings are constantly being led by the longing for a feeling of spiritual openness and enlightenment. When I think of this human longing, of searching and looking for a sense of eruption, there’s also a great vulnerability in that. Every time I’ve had these experiences of rupturing and healing, it always came with a torrent of grief. That’s also where I get this term from like expulsion: this sense of being cracked open. Loss has led to the most painful and the most beautiful transformative experiences of my life. There’s an analogy I always think of: somebody gives you a set of hot, rusted keys, and nobody wants to hold them because they burn your hands. But then when you do hold them and sit with the discomfort til they cool, you can use the key as a tool to open up new parts of yourself.

You said in another interview that you’re attracted to vessels and objects that have these connections to other narratives. Could you elaborate on that?

I find it fascinating how human beings try to connect to spirit: this striving to feel more than body, more than mind. I’ve always been enamored with objects of worship—how as humans we create these shrines. When we all collectively put energy into one object, projecting all this thought and emotional dependence onto a material thing, it’s like a form of magic—it almost comes alive. It means everything, but it also means nothing. Similarly, these paintings can mean so much when I’m doing them, but they also mean nothing; they’re just pigment on canvas. There’s such poetry to that, and it also relates like objects of worship: How much potency can you put in one piece of material?

My work as a painter is such a private experience; I’m someone who gets addicted to being alone, and I’ve had, in the past, obsessions with building little shrines and sitting with objects and collecting trinkets, treasures, remnants. And there are also portals to at least make us feel like we are traveling to another realm. New age groups use holy water, like in ancient cultures, and I think it’s beautiful—but there’s also an element of make-believe, a childishness to that. And I think perhaps that’s why my paintings carry a sense of unease but also belief, wonderment, and a bit of madness as well. I wanted the show to be a journey, almost like a fairy tale: how there are moments of beauty and sacrilege and fear and perhaps a little bit of horror. I want it to feel like you are in the midst of a spell.

Left: Love Belt, 2023

Right: Warm Chains, 2023

Left: Fool’s Arcadia, 2023

Right: Vial, 2023

Your paintings are so dreamlike they make me wonder: What are your dreams like?

When I was a child, I would be extremely taken by my dreams. I had different phases of sleepwalking, where I would walk around my house with my eyes open. Sometimes I would even wake up and be conscious, but I would see everything [as though I was] still in the dream—all my visuals were in a different place, but at the same time, I was coherent. One time I woke up and I was very much convinced I was Alice in Wonderland. I even woke my dad up and said I don’t know what to do, I’m growing out of our house! I remember being quite embarrassed about it. Another time I was walking up and down my house, and I couldn’t stop moving my arms. It was almost like Sydenham's chorea, that jerky kind of bodily illness at the turn of the century.

So yeah—lots of things have come out in dreamtime! I think dreams are so interesting, and kind of like painting: a process in which the psychological phantasmagoria of daily experience is regurgitated. When I would sleepwalk as a child, I was between a state of dream and conscious reality. And it goes back to these spaces I love: the in-between space, the void between two realms. Most of the paintings, if they’re in a landscape, it’s always twilight. It’s my favorite time, that space between night and day, between the lightness and the darkness. The day’s ended, it’s already like a faded memory… It’s already happened, and you can’t go back to it—and then it’s the mystery of the night.

Tali Lennox: Tremors is on view at Nicodim Gallery in Los Angeles through April 6.

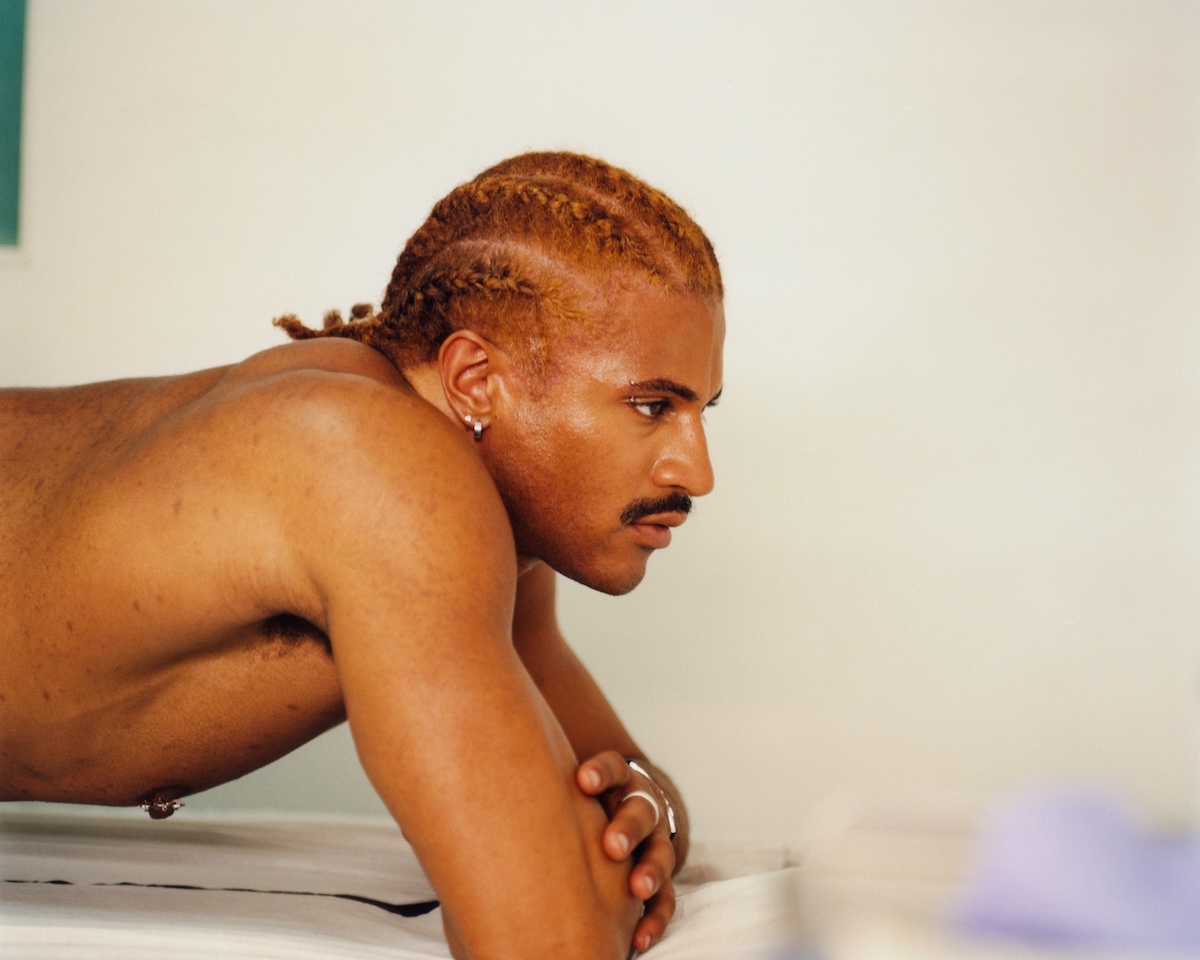

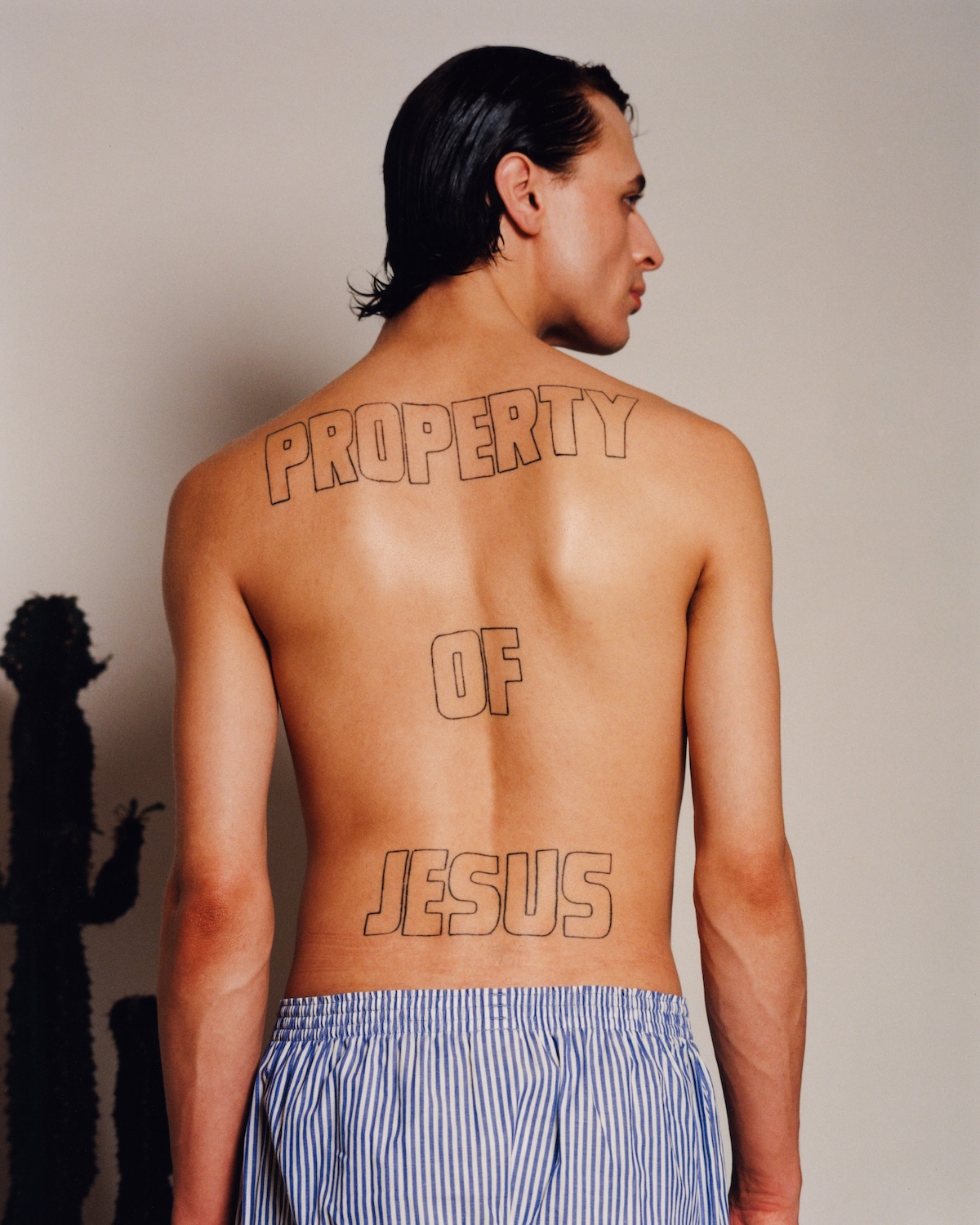

We meet at Friend Editions, where Ezekiel's photos and books are displayed. In talking about the Cruising story, they note the support they received from their parents. Both of us come from Catholic school and FIlipino immigrants — we were both rightfully surprised. Apparently their mom is still trying to get them to become a priest. I’m in a suit, they’re in a skirt, the situational irony is not lost upon either of us. But, even if their parents didn’t get their queer erotic photography, the support is still endearing. Apparently, while shooting, Ezekiel’s father had been excited to drive everyone around, beaming after hearing there was a famous gay pornstar in his backseat.

While Volume 1 of SMUT consists of more documentary style snapshots of the lives of female friends who are sex workers, Volume 2 is a more of an editorial. Yet, as has been notably lacking in the fashion industry, there’s a level of respect and intimacy between photographer and model, evident in how Ezekiel speaks of the production of their book. They reminisce on each model by name — friends, pornstars, friends who are pornstars, gogoboys, and someone’s silver fox uncle who was discovered at a wedding — who was apparently so excited to get spanked on camera, that he bought a train ticket to London for the entire day.

office — What was your first introduction to porn?

Ezekiel — I would say my first intro to ‘pornographic’ material was when we immigrated to the UK in the early 2000s and the top shelves of British corner shops (aka bodegas) would be lined with ‘Lads Mags’ such as Zoo and Nuts magazines, which would often have a half-naked or provocatively posed woman on the front cover. In terms of my first pornographic video, I remember it quite vividly. It was a homemade tape of some old guy masturbating that was uploaded onto Xvideos, which I secretly watched on the family computer whilst the rest of my family were out (sorry Mum and Dad).

Is there a relationship between the desire to observe and the desire to be observed?

Absolutely, especially in queer culture. Gay people have a tendency to be always looking for people like them, whether that be in a sexual manner or in a way to find comfort within spaces that are dominantly heterosexual. We just have a natural ability to find and gravitate towards each other in any situation. In my opinion, to be observed is to be acknowledged and seen, and the desire to be observed is a desire to exist.

Some people theorize that identity construction relies on performance for an audience — whether it be real or imaginary. Do you believe in the internal voyeur?

That’s a very interesting take, I think the idea of identity construction via performance is prevalent now more than ever especially due to the digital age we live in. Everyone’s always performing (whether they like it or not) for some sort of audience. Some could say that day-to-day life is inherently performative, or even just being an adult; where you have to sort of perform the idea that you have a career and your whole life figured out. So to answer your question, yes, I do believe in an internal voyeur because it’s hard for the idea of external voyeurs not to seep inwards.

What's your voyeurist fantasy?

At this moment, my ideal fantasy is to not be perceived in any way shape or form. Basically just don’t look at me, but maybe do… But don’t tell me you’re watching of course, or else this wouldn’t be a voyeurist fantasy at all.

Some photos involve Ezekiel themself, adding a third layer of observation and making us question where we stand on the spectrum of watcher to watched. Ezekiel does this story referencing the phenomena of Sleep Streaming, where people will pretend to sleep on camera and undress as more donations come in. Performers feign ignorance and pretend to be aloof to the fact that they are being watched, despite the fact that they themselves were the ones who set up the stream, who positioned the camera, and who are secretly conscious and awaiting viewers. Is that not the case for the digital age? Are we all not just walking around SoHo hoping for some street photographer to catch us looking unbothered and offhandedly stylish? Are we all not subconscioiusly performing for the thousands of newly minted party photographers that seem to keep popping up around the city? Are we not all sometimes our own neighbor in the window?