Stored

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

With To Dream of Smoke, Allen merges his art practice and love of rap music. He explains the influence of rap on his work, “I love rap music because it's so thick with lingo and many times very regionally specific terminology and accents that I wonder how much someone outside of this music culturally understands when listening?” This question of understanding and viewership is at the center of Allen’s exhibition, the latest entry in Allen’s “Body Surrogate” series which presents and reimagines representational depictions of Black masculinity. His pieces have been exhibited in spaces around the world including Screw Gallery, Galerie Kandlhofer, Von Ammon Co. and Icebox Project Space.

- The Race 1, 2023-2024

Allen uses late 2010’s viral rapper Tay K as an entry point to force viewers to confront our complicity in systems that force Black boys into survival tactics. In The Race, he juxtaposes Tay K’s first photo posted from jail with the platinum certification for his song "The Race" aligning them with a shattered hand mirror. The piece shows the disconnect between the commercial success of Tay K’s brief rap career and the broken systems currently shaping his life. He asks us to reconsider the media portrayals of Tay K, “How much can we judge the actions of a child fighting for survival, what if instead of just punishing him, we punished the society that failed him?”

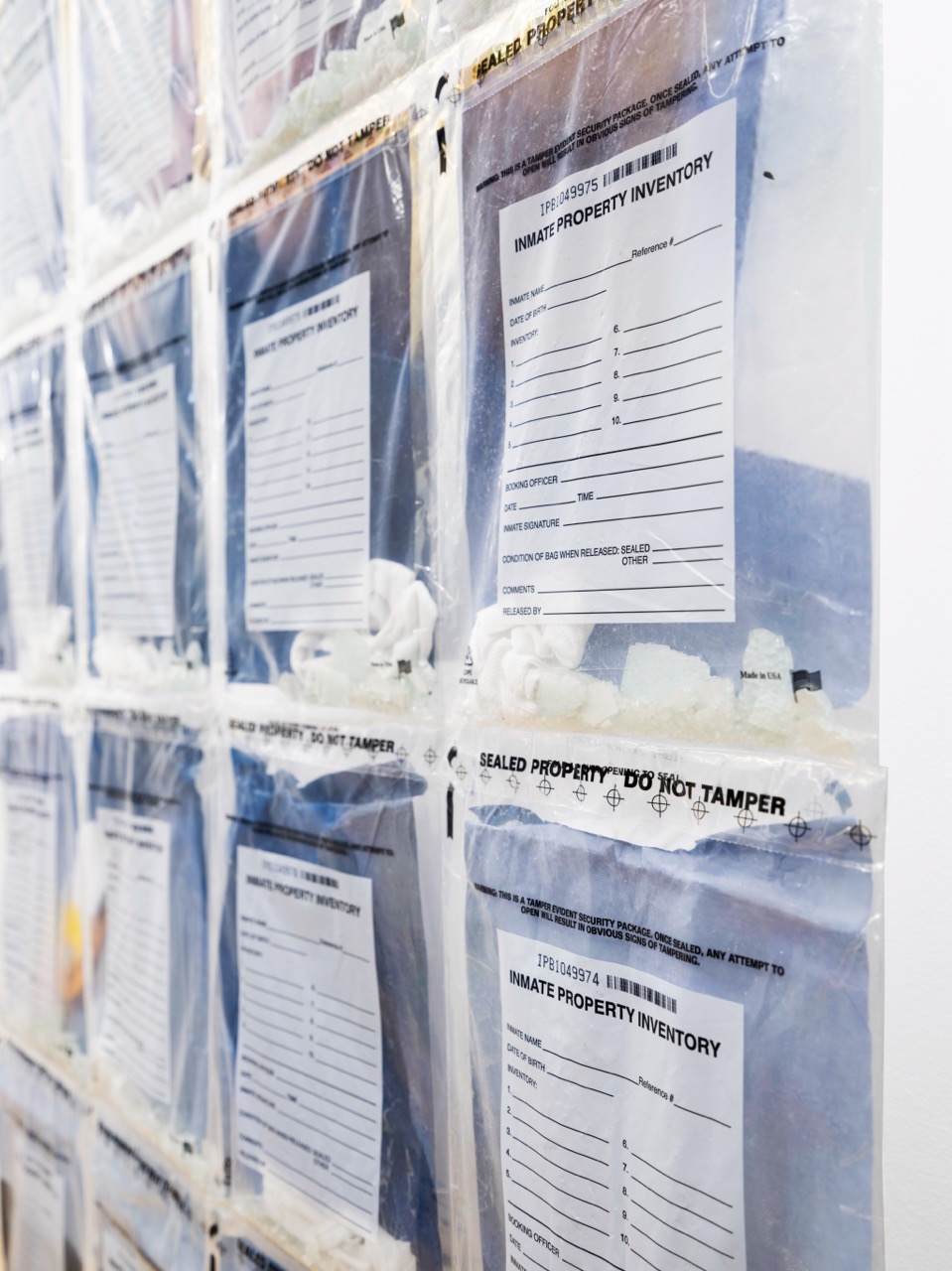

- The Race 2, 2024

In The Race 2, Allen takes inspiration from Gil Scott Heron’s “Pieces of a Man" and recreates the photo of Tay K through an assemblage of inmate property inventory bags. In addition, the bags contain a shredded shirt and shattered glass. Using this construction, he visualizes the dehumanization and humiliation that occurs within the United States’ prison system.

- Untitled (self portrait), 2024

In Untitled (self portrait), Allen pairs a portrait of Maryland rapper Q Da Fool with a ski mask stretched over a bag of powdered sugar. He tells me about the encounter that inspired the piece, "I used to wear ski masks to try and look tough or unapproachable. One time, someone came right up to me and felt at ease talking to me because of my soft, even sweet eyes”. Through this interrogation of Black masculinity and its performance, Allen questions the desire to appear intimidating in the first place.

- I Choose Violence, 2024

In I Choose Violence, Allen draws attention to the mental health crises within the Black community particularly impacting Black men. The piece which consists of photographs and scales is named after the song “I Choose Violence” by Atlanta rapper Glokk40spaz, Allen was inspired by a line in the song where Glokk40spaz alludes to self harm. Allen was taken aback by this break in armor and related through his own struggles around body dysmorphia and an eating disorder. These experiences are aligned in the piece through the grouping of a bathroom scale and digital scale for weighing drugs.

Catch To Dream of Smoke at No Gallery before it goes.

At the core of “Miss Understand” is a celebration of the divine feminine, or the spark that birthed humanity into existence, as well as a profound respect and admiration for the resilience of women to embrace the multidimensionality of their identities from within a society that has historically limited their agency to do so. She achieves this by masterfully invoking a visual language of repeating symbols: eyes, lit candles, fleshy body parts, serpents, and Barbies, etc. that seemingly invites the viewer to try and connect the dots while at the same time resisting the very idea that there is a rational or logical way to view or experience life or the exhibition. "Miss Understand" was on view at Templon Gallery in NYC through March 9th, 2024.

Emann Odufu: It took me a while to process the exhibition. I was initially overwhelmed by that level of detail. I was at the exhibition in the installation space with some friends, and we heard a humming noise coming from a box. It took us a second to realize that the box was a refrigerator. We opened it up, and there were apples in the fridge.

It wasn't until I started to look at Miss Understand as a character that I began to see her not as a representation of you solely as an artist but as a holistic representation of femininity in the modern world that I began to wrap my head around the exhibition. Miss Understand felt like a play on Miss Universe and every woman. My first question is for you, the artist, who is Miss Understand?

Oda Jaune: I’m so happy that you opened the door of the refrigerator. When I was working on the installation, I loved to imagine the viewer to experience the exhibition with their eyes and hands and to lie down on the bed, sit on the chairs, discover the overpainted books, and spend time in the space so they become part of the installation themselves.

“Miss Understand” is not a particular woman. It is not me. It is no woman and at the same time maybe every woman. It’s also for everybody who feels like a woman. I came up with the title on a walk with my daughter. We were looking at people's T-shirts because there was often a slogan written on them. She asked me if I had to design a t-shirt with only text, what would it be. The first thing that came to my mind was “Miss Understand” and I said that I would divide the word into two.

It's something in the nature of the woman that it is impossible to be understood. Extending it further, I think it’s in the nature of a human to not to be understood. How absurd is it to me that we are living in a time of so many numbers, facts, algorithms and scientific proofs that bring us further away from (our) nature. We're forgetting about magic and things that are not so easy to understand. When you have the feeling and understand something, you put it in a box, label it and maybe you get a key and close the file forever and say “Oh, this is this way” and you are limiting yourself. I feel almost allergic to the idea of labeling the world, people, history, everything that we try to put in a box.

Within the work there may be questions for the viewer, for their answers to arise but they don't need to position themselves and don't need to judge. Our world is so polarized. You must choose left or right, for or against, which constantly puts us in separation and division. How about making it more open for us to make mistakes and for misunderstandings and more freedom?

EO: I think that that makes a lot of sense. I saw that throughout the show, there's this idea of subverting duality or this idea that in the process of misunderstanding, there's this sort of mystery that is confronted and acknowledged. As the viewer, you see the exhibition and try to make sense of it all, but try as you may, you won't see it from the vantage point of you, the artist, and It's almost futile to try to understand.

I want to talk about the performance art piece happening on the show's last day, which I'm excited to see, and where you will animate Miss Understand in a personified form. As an artist, I love that you dig into the multidisciplinary aspect of your practice and constantly push the limitations of how you engage with your audience. I read that in the last show at Templon in Paris, you had a hologram of the Tree of Life, and now you're activating this current exhibition through performance art. Can you talk about how you're constantly reinventing your practice and your approach to toggling between these various mediums as you engage your audience?

OJ: I love that you found information and the little journey that I had with the hologram. I loved it because it was the pandemic, and the real situation where we could reset individually and as a society. I was asking existential questions, and I thought about how we're living in a world that is, for me, even though it's so dominated by inventions of our time, it is still quite magical. It's almost like another reality within our reality. I was working on this show during covid lockdown thinking about how there’s something invisible you couldn't see, you know it's in the air. I found it fascinating that we were in such a frenzy over something invisible and how it could, for a moment, change everything in our world. This thought process around visible and invisible, tangible and translucent, leads to an interest in holograms. The more I researched, I understood that I would have to create my own technique for creating a hologram, because the best things happen when you have a limited budget.

I said “OK, let's think about what we can do if we improvise.” So we created something, and it actually worked. It was like magic because we didn't have much, and it was such an improvisation and the people who loved it from all age groups were touched by it. For me, it's about how real I can make an idea and what techniques permit me to execute those visions.

I was trained as a painter and when I was younger, I really loved observing the human body. I thought it's just so incredible. Humans in general. I really love nature and observing the light and the shadow and how everything changes constantly. I honestly don't remember a moment in my life when I have been bored. What a stunning experience it is having eyes. Painting oil on canvas is the closest I can come to what I have as a vision. At some point, I reached a stage where I can paint everything that I imagine, so I created sculpture to see how I would feel when my ideas become three dimensional. When I was a young girl, I loved working with clay, the softness of it. I was also intrigued by wood and stone, marble but then I was told that, because I was a woman, I would only be able to work on small things because physically I would never be able to do what men can. I accepted that and focused on painting. Because I wanted to be as free as possible as an artist and I do love painting in an unconventional way, but I didn’t stop loving sculptures, so later I reapproached sculpture again.

One day, my daughter asked me if I wasn’t a painter what I would do in my next life. I realized that I would love to do movies, but I want to do movies that I only need to do myself. That's why there are six short videos in the exhibition and I loved making them.

EO: I'm also a filmmaker, and when I was in the installation, I thought that as I looked at the videos, whether you are shooting the videos with a crew or you're shooting them yourself.

Alone. I really love making films, combining pictures and sounds. The whole thing is moving. With painting, you have just one shot. A study found that visitors look for less than two seconds, turn and read the explanatory text for an additional 10 seconds and then move on. So, you have to decide which moment to paint and that takes months and months in order to make a difference in a span of seconds.

EO: And now you're venturing into performance art.

OJ: I am very excited though about the performance art piece because Claudia is a very special human being that I love as a dear friend. One day, she showed me something with her hands and the way she moved her finger in a way to symbolize humans, it was like a symphony, and I imagined it as a whole movie. I asked her if she wanted to collaborate for the exhibition. I love to imagine what she is going to do and love not knowing what is going to happen on that day. It’s the same with all of my paintings. When I start painting, I never know what's going to happen. What I dream of is creating a feeling of “Miss Understand “ being a real human - only the feeling that was at the core of our collaboration for the performance you are going to see on the final last day of the show. The aim was to put this feeling in a real human that will grow and materialize itself in a living, moving, breathing, heart beating woman inside the gallery space for 8 hours existing as real as every one of us. Claudia will be performing and the viewer can enter the space and decide how close and involved they want to be. Claudia Hilda is for me one of the most incredible artists with that one of a kind ability to become a pure feeling by giving up on all she is, on all knowledge and abilities, techniques and styles she has, the language, the speech to become Miss Understand.

EO: There is a quality of artistic rebellion in your work that I enjoy. Both aesthetically and with the symbols you use very well. The viewer's experience of your work has been described as deciphering a crossword puzzle, a complex web of various cues that appear from out of your subconscious and that force the viewer to confront their relation to the world and their internal belief systems. Miss Understand does not exist in a vacuum and builds on a visual language you have built throughout your career. It's a language only you speak, but the viewer can feel it. As an artist, how did you come to know yourself in such a way that you can render your subconscious into a visual language that people can feel?

OJ: I don't know but I'm going to search for an answer to give you. The thing I can tell you is that I can't work if there is somebody else around me. If there is someone else in the studio, I never reach the concentration that I need to forget the outside world. I start with something that moves me. There are certain things where there is a longing. Something I am deeply moved by, something I can’t find peace with unless I can transform it and bring it to the other side.

It doesn’t even need to be politics; it can be something like how we come into this world without choosing where and when you are dropped here and then you deal with it and then on top of that you're going to be taken away at a certain moment. Maybe this is what I really don't like as a feeling, probably like all of us I don’t like the feeling of fear or the feeling of not being able to change things or that I don’t have any power to make a change. In a way, I search for a way to deal with the reality of what is really happening in the world with eyes wide open. I reject closing them. These things move me and touch me, and I want to fight. I did start as a child with the dream to change the world. I suppose painting was my tool.

When I was 12, I moved to Germany. I could not speak the language and the kids were kind of cruel and thought I was stupid. I really couldn't express myself, I just had the basics. So, I started drawing to communicate and it worked. They were able to understand me. In this moment, I saw how many things you can say with an image. If you think of all the emojis that we send and how one heart emoji has thousands of words inside of it and there is something so open about it.

When I was a child I loved going to the library, and I would search for books with images, and I spent hours and hours and I would “read" through observing images. So, I think it's the way I get the most information. I believe my ideas come from tapping into my subconscious. It’s through the subconscious that everything comes. Your subconscious is working for you during the day and night when you're not conscious. It's a huge sea of everything and it has its own intelligence. For many centuries people believed a lot more in this other part of our intelligence and it’s a lot less respected these days. Today we are more confident about the visible things, the rational, the facts that can be scientifically proven. However, there is some truth on the other side and when I reach the point of being in tune with it, it is usually in the morning. I just love silence when I'm alone. I always start quite disciplined and controlled, but there comes the moment where all this control is lost and I’m working and not hungry and I don't know how fast time goes by, this is the most precious time and that is where the important decisions take place.

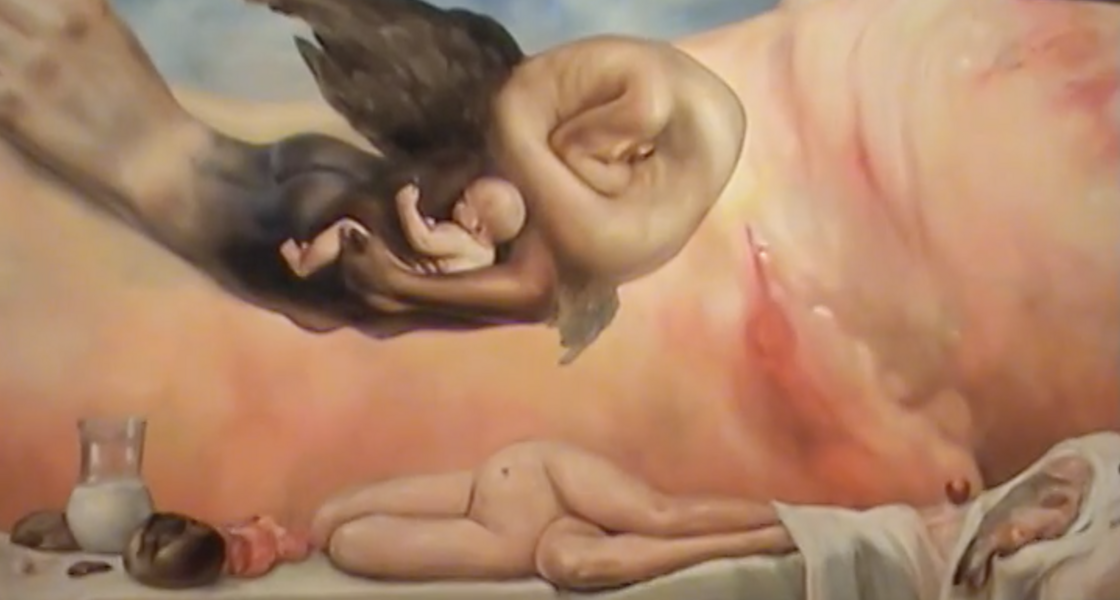

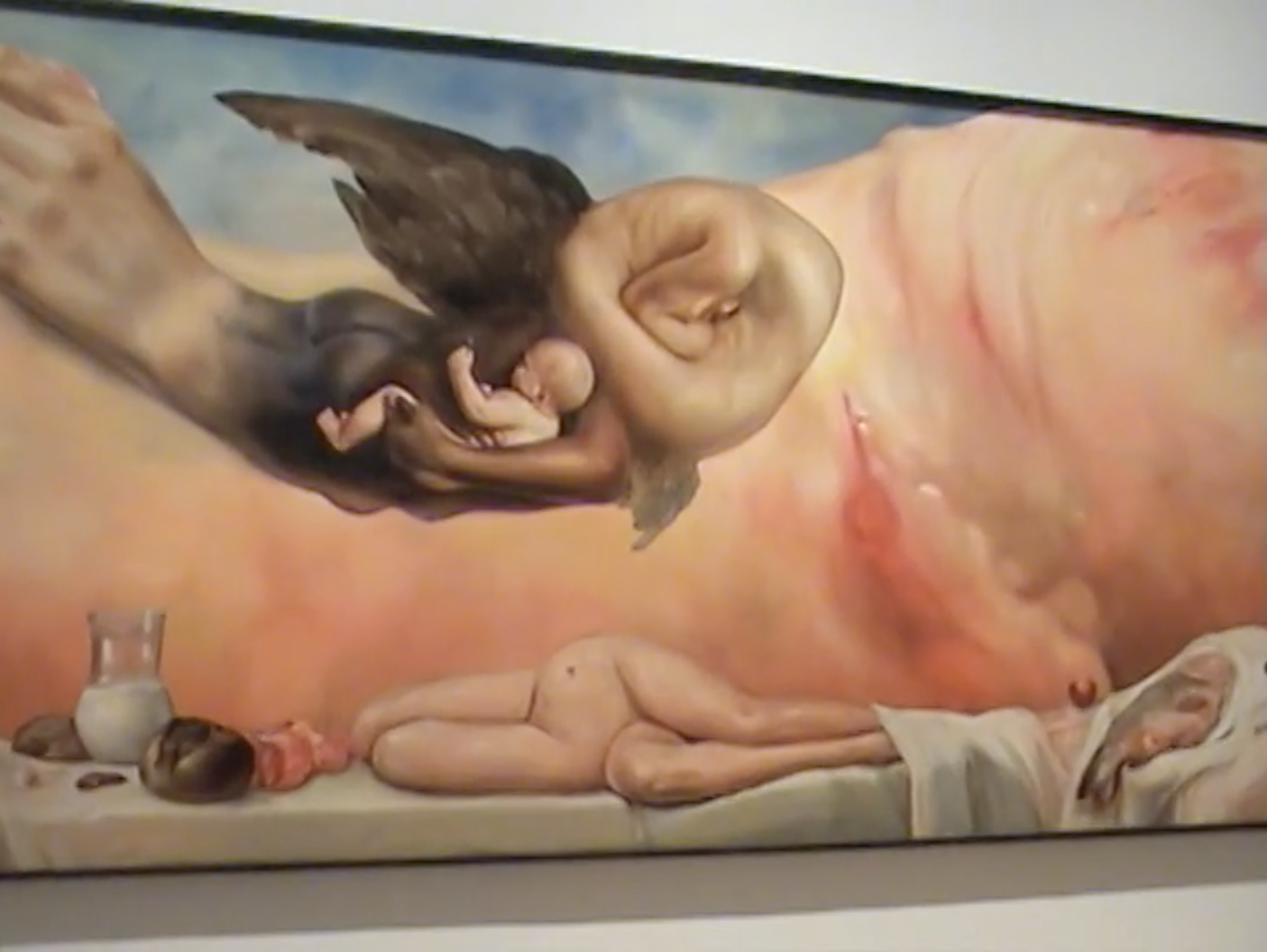

EO: Birth and creation ( to ourselves, to the other, to the world) is a strong theme in your practice In this exhibition we see the connection to Birth through your depictions of the womb and pink fleshy matter, most prominently in your work entitled "M is for Mother". It's also seen in your depiction or cap nod to the biblical creation story and how that has shaped the perception of women in modern culture. Can you reflect on this theme of Birth and Creation and how it's a thread carried throughout your practice and even into your artistic philosophy?

OJ: Someone told me you are born many times in your life, and you also die many times in your life and I love that, but I wanted to talk about the very first time. The biggest painting in the show M for Mother, is about coming to earth, dedicated to the one that gave us life, the biggest present, to the mother. We often think we have freedom of choice in life, but the biggest choice has been done for us, it is not done by ourselves. What happens? Where do we come from? It all begins with pain, the first breath you take on earth is painful and your mother will be in such pain. They say that when you're born several times in your life very often it happens after a very difficult situation and you're able to start a new life. One of the most dramatic things that can happen in life is having a chance to be reborn, reinvent yourself, to reset and start new. Many of the paintings capture moments of change or transformation. You have someone of something becoming something else.

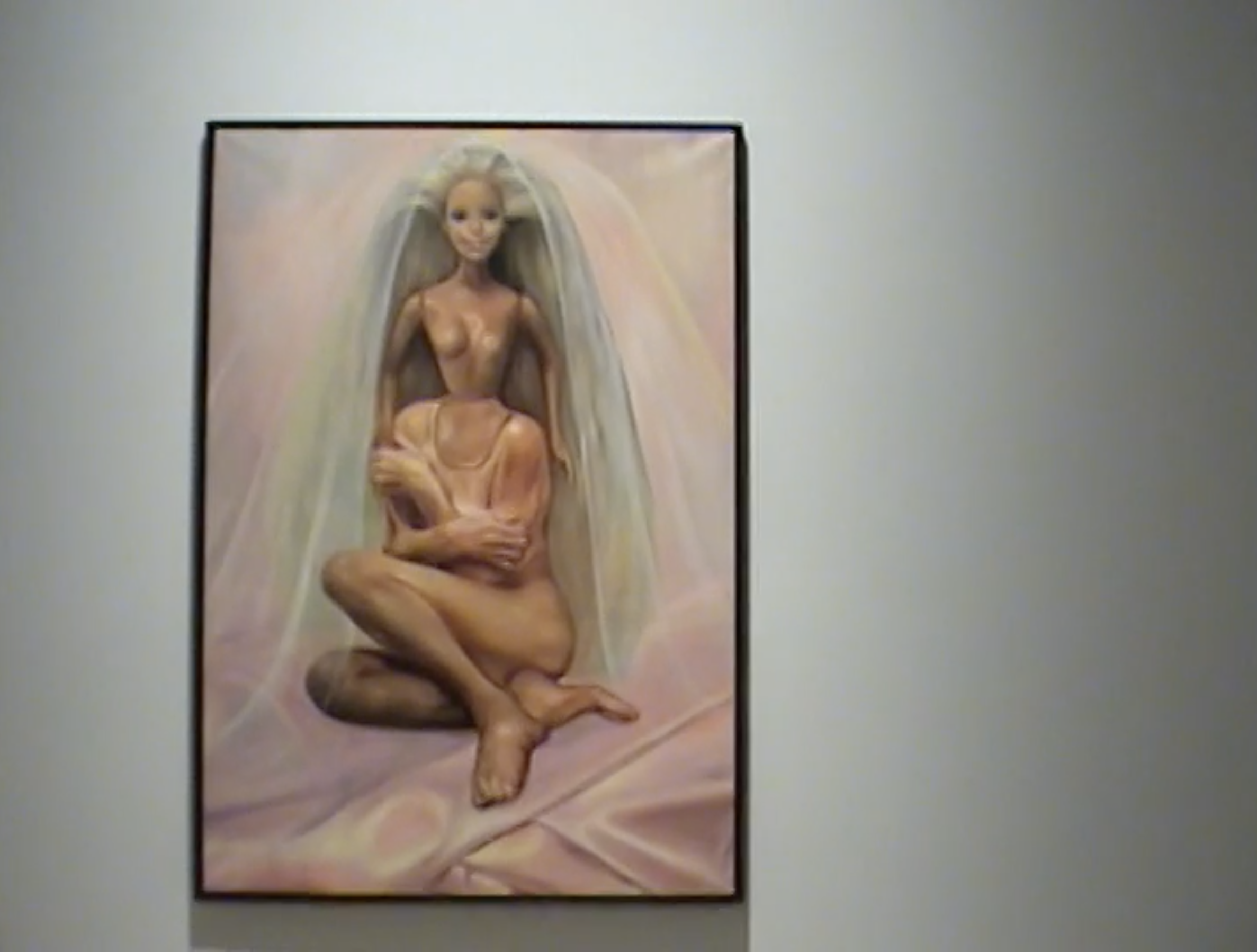

EO: One great example is "B, like Barbie."

OJ: Yes, B like Barbie is also about that. I had many barbies when I was a child and when I started painting this painting, I had no idea there would be a movie about it and it had nothing to do with that. When I was in New York, I went to see it, but I found that I just really wanted to fall asleep. I didn't watch it until the end, but what I did see was this constantly beautiful young plastic doll. But you are never the same. Depending on how you feel, how much sun you have taken in, how healthy you are, what you ate, how you slept, how much water you drink, you are never the same. Even after you go to sleep, your mind and feelings are still active because you had certain dreams that you might forget on the next day, but you change. Regardless if you forget your dreams, you are still altered by them. You are not the same. So this idea of one-dimensionality is problematic. Birth is something to be so grateful for and it is important to never forget that. At a certain point, there is so much thinking of who I am and not of how I have been born.

Pictured Above: 'B for Barbie,' 'M for Mother,' 'G like Guerrilla Girl' (2023)

Footage from the closing performance by Claudia Hilda below.

This one-of-a-kind vehicle integrates color-change technology with the signature colors and geometric patterns we’ve come to associate with Esther Mahlangu's work. To ensure the faithful recreation of every intricate detail of the ornate artwork, the BMW i5 Flow NOSTOKANA has been fitted with 1,349 individually controllable sections of film.

The complex colors and patterns showcased in the artwork offer a glimpse into the future potential for customized vehicles that fans of BMW’s innovation can look forward to. We took time from exploring the artwork to catch up with Stella Clarke, BMW’s research engineer as well as Esther Mahlangu in order to understand both of their perspectives.

What about Esther makes her the right artist for BMW to collaborate with?

Stella Clarke, Research Engineer Open Innovations, BMW Group - I think there's a number of things there. So, the journey to this car started about six years ago and before we even had prototypes, I had a pitch deck to try and convince people of using E Ink in a car. And at the very end of that pitch deck came a picture of her looking at her art on the dashboard with a huge smile on her face. And that was the moment where people understood what I wanted to do with E Ink. So that was really a key moment and a key inspiration for everything that happened after that.

Second of all, it just fits in really well together, her art with the idea of color change in multiple ways. Of course the art is very colorful and the ability to kind of change the color brings a dynamic element, a modernity into her art. Throughout the history of this African art from the Ndebele culture, there's also a certain progression in there. They started painting with earth colors, just colors of the materials that you had around. And then when acrylic colors came, they moved onto that and she was the first person to take this art and put it onto canvas. So innovation has always been a part of her and her art as well. And so this is a way to continue the story of innovation with her art on our car. And she did paint the 12th art car BMW art car, which is quite legendary. And so this was also a nice way for us to pay homage to her art car while also showcasing the innovative side of BMW.

How do you think her style and vision compliments BMW's design philosophy?

Stella Clarke - I think the playfulness of her art, and the joy in her art fits together with the joy of what BMW tries to bring to its customers and the products that we make.If you try to ask Esther philosophical questions about her art, she says she just wants to bring joy to people and she wants to kind of show her tradition to the world. And I think it's the same thing that BMW wants to try and do, bring joy. It's a part of our slogan, right? Bring joy to the customer. And also a certain amount of heritage is also in there with BMW, that we are also proud of.

Why do you feel it's important for BMW to merge the worlds of art and automotive design?

Stella Clarke - I think BMW has always supported the arts and here we're seeing a kind of fusion of art and innovation. And I think those two go hand in hand. I think something that's innovative and something that is creative is something that brings joy, brings light, perhaps even a certain amount of disbelief. And we've done this with our changing colors so far. We know that people often can't believe what they're looking at. And I think art often aims to do that as well, right? The art kind of aims to push your mind. It aims to delight, it aims to bring you joy as well. And I think that's how art and innovation can come together. So I think we can both learn from each other because we both have the goal of delighting and bringing joy to people.

Do you think art, and this collaboration in particular, will shift perceptions of traditional car design?

Stella Clarke - I think so. I think it's a wonderful playfulness that we're showing here. And I think not only this car, but the other cars that we've done with color change so far with E Ink. There, we showed cars that can change their colors and we know based on the reaction that people like to express themselves with their car. So this really brings a new element into car design. It means that you, yourself, every owner of their car can become their own designer. And at any given day, you can choose how you want to express yourself with your car. It's a new dimension in terms of car design.

What about BMW as a brand makes them the right fit for a collaboration?

Esther Mahlangu - I have a long and mutually beneficial relationship with BMW that goes back to 1991. They have proven their interest and commitment to art over many decades through the BMW Art Car Collection, sponsorship of art fairs, work with museums, and now my Retrospective Exhibition and the tour thereof.

What considerations have to be made when collaborating with such a big company like BMW?

Esther Mahlangu - BMW has been very easy to work with. I have not had to consider many things in our collaborations. They have proposed different projects to me which I have agreed to do and they have been very successful. My gallerist proposed my Retrospective Exhibition to them, and they agreed to support it for which I am grateful.

Were there any creative limitations?

Esther Mahlangu - There have not been any creative limitations other than the medium itself. They have provided me with a car, and I have looked at it as a medium on which to paint or apply my designs.

What elements of the artwork do you feel speak most to your South African heritage?

Esther Mahlangu - I was taught the art of Ndebele design as a young girl as is tradition amongst my people. Everything about what I create is therefore closely associated to South Africa, something of which I am very proud.

Has there been a shift in the creative process since the first BMW collaboration in 1991?

Esther Mahlangu - My last two projects with BMW have been very different from our first collaboration in 1991 as they did not require me to paint onto the vehicle. Both used the latest technology to apply my designs to the cars.

Was it difficult to adapt to and welcome technology into the fold?

Esther Mahlangu - It was a simple process to include my designs whilst I expect that it was more difficult to come up with the technology that allowed for this.