Stored

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

The world, at least in 1937, seems to have agreed on the powers of the lamb. That year, the artist Paul Cadmus opened his first solo show at Midtown Gallery in New York boasting artworks of male physiques and satires of American nightlife. Everything from his show sold out. It drew a record-breaking audience of seven thousand homosocially curious lions, lured in by an artist compelled to depict men as if they were potent lambs as evinced in his painting, Y.M.C.A. Locker Room, 1933. It was all very gay. For this, the artist garnered mainstream attention and inclusion in art history. Life magazine fueled America's intrigue, emphasizing Cadmus’ cheeky fascination for depicting, “the play of muscles and the stretch of skin above them.” (Incidentally, Cadmus’ men appear with little if any visible signs of body hair, resembling sheared lambs free of wool coats, perhaps something de Beauvoir would have found less repulsive).

A few years later, the 1941 Encyclopedia Britannica entry for ‘Famous Paintings by Modern American Artists’ linked Cadmus with Regionalists Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry and soft psycho-realist Edward Hopper. This moment of late American modernism would not last. Like all movements in art history, they, too, were succeeded by another scene. Cadmus was met with fierce condemnation and brutal acts of censorship for his boisterous tableaus of cross-class contact rich with sexual innuendos while his less gay peers were succeeded by the Abstract Expressionists. The Ab Ex painters were sponsored by clandestine CIA “donations,” and written with great esteem by academic art critics weaponizing their institutional powers of intellectual prestige to refashion history, whether that of art or sexuality, to their own liking.

History loves persecuting sexual minorities. There is no exception to this, not even from the ancient Greeks who were rather generous with their sculptures of naked mortals, demi-gods, nymphs, and goddesses. In response to an email I wrote to A.B. Huber, one of my undergraduate thesis advisors, Huber shared this anecdote, “I kept thinking about the fact that when the first stele of hermaphroditic figures were being made in Greece, actual intersex babies were ‘put out to sea,’ that is exposed and drowned as monstrosities that threatened the community. Sometimes non-normative bodies are celebrated in art or ritual objects but loathed in reality.” Why is the reality of everyday life often overlooked, censored in art history?

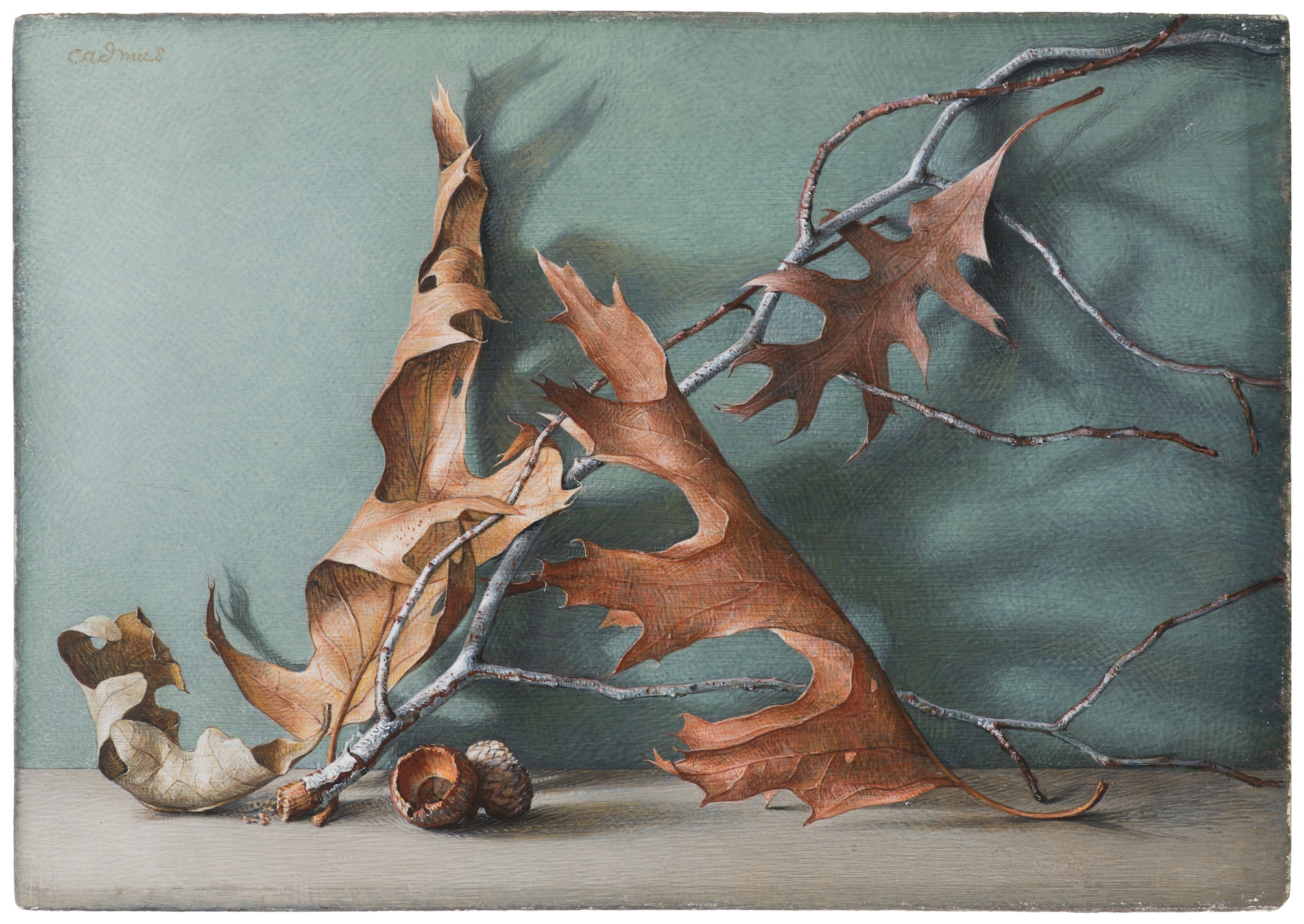

Whatever, for Cadmus and Cadmus’ friends, life was always a beach. In February of 2024, D.C. Moore gallery showed the artist’s first major show in over 20 years, Paul Cadmus: The Male Nude. It relied heavily on works of beauties traversing Fire Island’s sandy shoreline, beachside mansions, and White Oak and Red Swamp maple-covered loveshacks (Camp Cheerful, 1939; Pine Cone and Bark, 1955; and, Winter Still Life, 1970). They circulate across the gallery’s scarlet-colored walls. There are several still lives and dozens of nude figures drawn with fast, fluid marks or painted with egg tempera and highlighted with crayon. His figures have flesh that bulges or twists similar to artists like Tom of Finland or Jiraiya. However, what distinguishes Cadmus from these guys is that his figures appear to glow to the point of otherworldly enchantment.

Some figures read and eat apples at the beach like in Two Boys on a Beach, c. 1936. Nearby a boy yawns. Others lounge at ease and yet appear to be stretching. It’s uncanny.

Narcissus: Study for an Homage to Caravaggio, 1963, 1983

Tempera and ink on board, ca. 1963; crayon added in 1983

Collection of The Tobin Theatre Arts Fund, 75.2007.

Courtesy of the McNay Art Museum, San Antonio,Texas.

A luminescent boy in one tempera, ink, and crayon drawing, Narcissus: Study for an Homage to Caravaggio, 1963, 1983, lays sprawled out on a bed of Fire Island’s feathery grasses, like soft rush and switchgrass. His gnarly, lean flesh folds around himself as if frozen mid-motion while tumbling downhill. His firm ass protrudes at the center of the drawing. He arches his back. It creates a nice shadow-line that runs through the length of his spine. His neck, head, and blonde and white curls all meet at the end line. His head along with an outstretched left arm fall off a bayside barrier. They hover above murky saltwater located at the bottom of the drawing. His head peers downward into the water while his fingers reach out to his reflection. In this intricate tableau, the boy becomes a focal point, not merely a subject but a representation of desire itself. His naked form, frozen yet seemingly in motion, with an outstretched arm drawn in a phallic manner, invites his reflection as well as the viewer into the scene. His outstretched arm inches closer to the picture plane, coming towards the viewer. The viewer stands outside the picture, wading nearby in the salt water just beyond the boy’s reflection. Here, the artist blurs the boundaries between observer and observed, lover and beloved.

Cadmus was a huge fan of triangulations. The triangulation inherent in this composition echoes the complexities of attraction, where the paradoxical interplay of both the law of desire and the rule of seduction unfold. Something to mention, especially, about desire and seduction: desire follows the law of gratification whereas seduction follows the rule of intensification. For the desiring subject who breaks the law of desire, they are punished. But like most lawbreakers, they’re given another chance to play again once penance has been paid. Seduction does not let you play again. It follows the rule — not the law — of intensification. Once the seducer breaks the rule of intensification (becoming avoidant, anxious, or secure to the point of barrier breaking intimacy i.e. empathy) they must exit the scene. The game of attraction ends.

Between the boy, his reflection, and the viewer positioned just outside the frame, a delicate dance assembles. The boy's gaze fixates upon his own image. It’s a gratifying manifestation of his beauty. But granting that gratification threatens to extinguish desire itself. In most versions of the story of Narcissus, the boy dies once he falls into his reflection. If this drawn boy falls into the water, he would be breaking the rule of seduction — not desire — by choosing to end his life. Instead, he intensifies seduction by continuing his gaze as he reaches out to the viewer. His beckoning gesture asks the viewer to participate in this erotic scene. We, the viewer, are gratified by him including us in the scene. His hand calls for the viewer to make a decision: to grab his hand and roll along with him on solid ground or to pull him underwater. Here is both desire and seduction continuously at play. The boy's control over the scene is tenuous, contingent upon the triangulating motion of desire and seduction. The story only continues, though, if the viewer grabs his hand and joins his decelerating tumble.

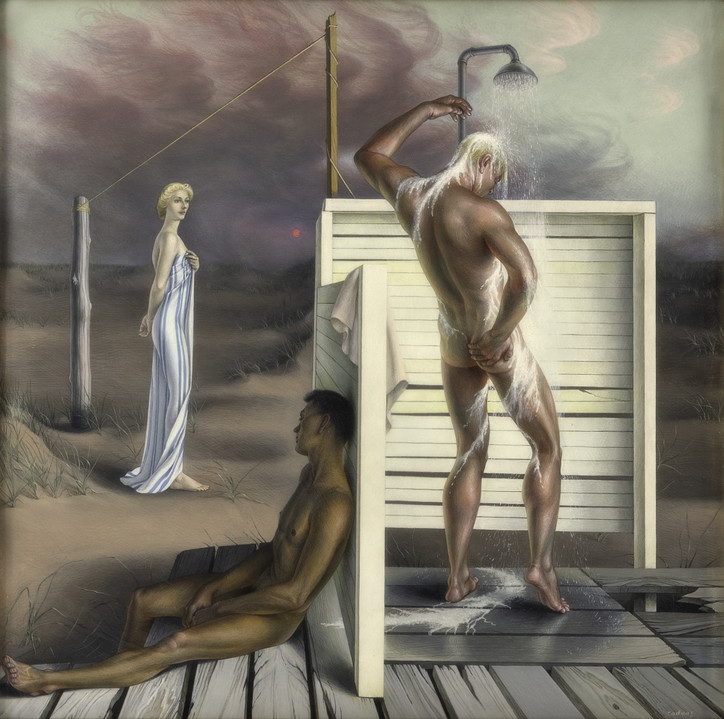

The Shower, 1943

Egg tempera on pressed wood panel

15 1/4x15 1/2inches

Private Collection

Elsewhere in the show, there's a painting showing a hunk covered in droplets and soapy suds. He is enjoying an outdoor shower (The Shower, 1943). A woman wrapped in a bed cloth watches as a wildfire summer sun burns behind her. Below the hunk is a skinny man who reclines, patiently waiting to be summoned by either of these two lovers. Again, triangulations were no stranger to Cadmus’ artistry and life. The artist took part in a collective with Jared French, Margaret French, and himself, colloquially called PAJAMA as shown in the photograph on display, Paul Cadmus and Jared French, Fire Island, 1941. The throuple lasted for a significant portion of his life. This was brought up several times during a packed-house conversation on the legacy of Paul Cadmus and Fire Island this winter. The conversation was shared between art critic Justin Spring, BOFFO co-founder Faris Saad Al-Shathir, and photographer Matthew Leifheit. But, the artist was more than his triangulations. He collaborated with a cohort of mostly white creatives like the photographer George Platt Lynes, Lynes’ on again off again lover, the MoMa curator Monroe Wheeler, and the painter George Tooker. In reality, these were his companions. This was the art historical movement in which he found pleasure and safety to be himself. He helped build it and so he belonged to it.

One of the artist’s favorite scenes was wherever water meets land. More often than not his scene was the beach. In the most literal sense of the word, a scene is a moment of “intense affection,” similar to scenes found in a book or a movie. They also appear in drawings and paintings. Social scenes, too, are moments of “intense affection” where both pleasure and safety are interconnected at a much larger scale. What feels special about Cadmus was his knowingness that much of his scene wouldn't last. He navigated his faggy way of life, the polyamory, the earnest pursuit of some idealized human form, the thumbnails of bullish men, sailors, twinks, trade, glammed out dolls, gangsters, hookers, beefs, queens, faeries, all entangled and enthralled with one another.

The Fleet’s In!, 1934

Etching

7 1/4 x 14 1/8 inches

D.C. Moore’s founder Bridget Moore added to the conversation noting that the government did not value a lot of the artwork created for the United States Public Works of Art Project (WPA) after the war and, unbelievably, sold many paintings for linen scrap for pipe fittings. These works, along with artworks by Cadmus' peers were sold at garage sales or thrift stores. Further to the point of trash, it’s no surprise that one of Cadmus' paintings made while a member of the federal government funded WPA was removed from public view. Perhaps it was because he was outing all sorts of men in the military. “In 1934, one of Cadmus’ very gay paintings, The Fleet's In!, 1934 (it would later inspire a major motion picture), was quickly removed from public display. It was stolen by a retired navy admiral who, contradictorily, installed it at a men's-only Alibi Club in Washington, D.C. It lived there for four decades. A year before Cadmus' The Fleet's In! was removed, Diego Riviera had his mural burnt off the wall of Rockefeller Center because he wouldn’t remove his portrait of Lenin from the center of it. All the best artists were queer communists,” shared an audience member during the conversation’s Q & A. By outing the whole military, did Cadmus fuel military turmoil?

Spring confidently responded. He seemed to think this was most likely not the case. He noted that figuration in art history has always been queer and that Cadmus’ practice of queer realism by means of figuration was not all that political. The critic seemed to be missing what the audience member was suggesting. Said audience member responded, “I suppose I agree with you that figuration has always been queer (because people are),” echoing Huber. “However, America did put Cadmus’ style of figuration entirely back into the closet to avoid the issue of America’s very public queerness. America wasn't ready for queer figuration, but Cadmus was insisting on it 90 years ago!” furthering Huber’s illustrative example. The packed gallery stirred at the lamb's captivating come-on. A faint smile materialized on the critic's face, begrudgingly acknowledging the lamb's charm.

There’s more to share. Continuing de Beauvoir’s observation, she notes that, "If the prehensile, possessive tendency exists more strongly in women, her orientation... will be toward homosexuality." Here, de Beauvoir is not wrong. Homosexuals, those women attracted to women or men attracted to men, have an intimate understanding of attraction’s complexities and know best how to navigate, if not totally transfigure, scenes of intense affection and desire. They tend to extend beyond the conventional roles of lion and lamb, lover and beloved. At times, the lamb turns out to be a wolf in grown up lamb’s clothing.

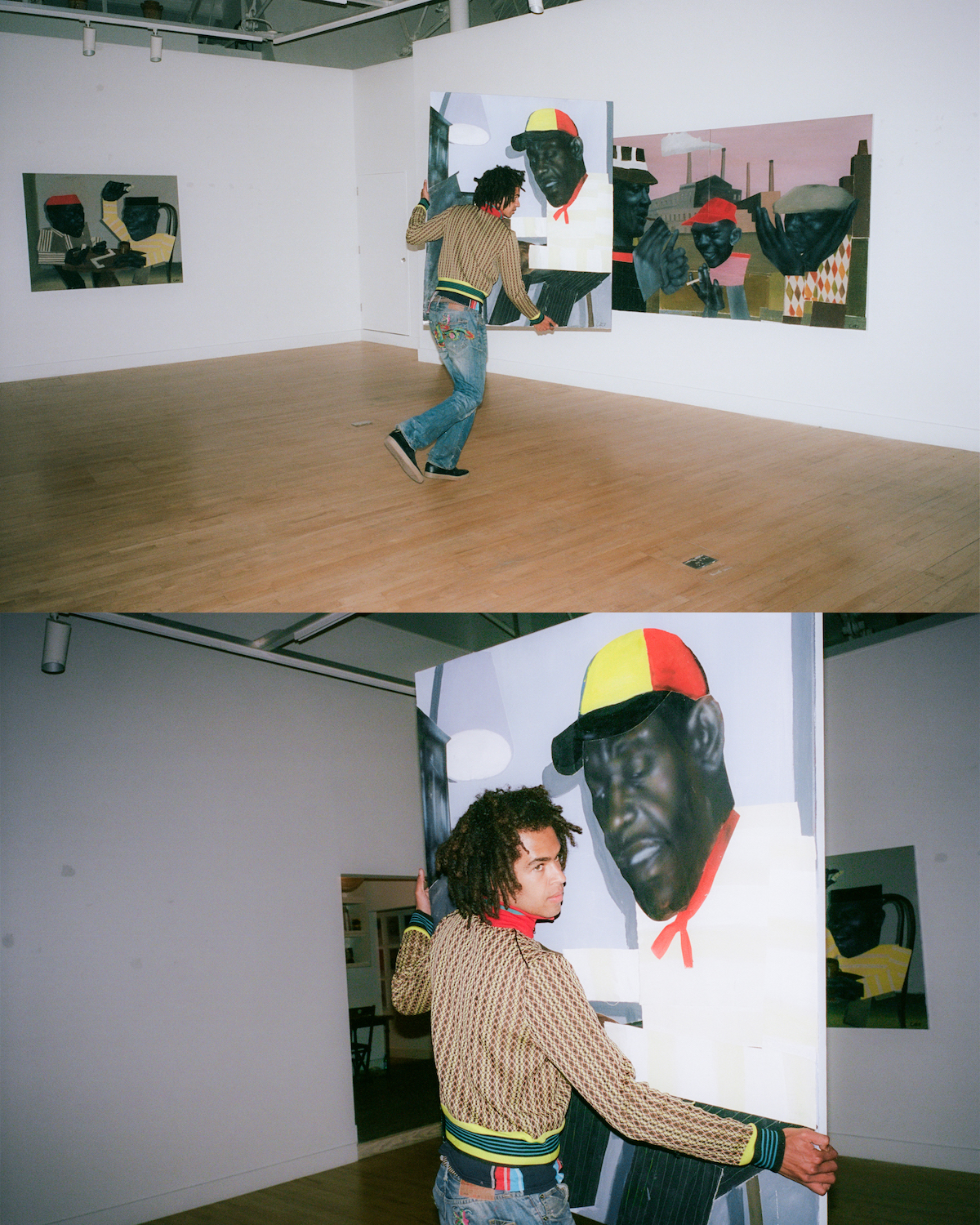

Tell me about your current show SEEN! that is opening imminently.

The [Cooke Latham] gallery were the first people to offer me a solo show, so that was really exciting. The LA show happened quicker… but for this it was the first time I was in my studio in London, working on paintings that would have to work together on four walls, and that was really fun.

What was your methodology behind this show?

What I wanted to do was introduce taking my own photographs and finding real characters, Caribbean people in Peckham and Brixton, to photograph. So I asked these casting agents to find older people to come round the studio to take portraits of, which I took with my sister Maya and her boyfriend Dominic (who work under MISSOHIO as a photography duo). I started by collecting photos of people with really cool expressions and next was my research of African photographers to find the right characters that spark my imagination. Then I paint those faces first on stretched canvas and start pairing things together. I paint with acrylic and airbrush until they start talking to each other within the painting and then I build their bodies and stuff around that.

One of the guys who came, who's called Tony Culture, had a sick outfit so that just made it easy because I could use his whole vibe for one of the paintings, which is the one I posted first. So I just try to make little moments, little scenes with those characters.

And I know your work also hinges on art histories to an extent too…

I’m influenced by photographers like Malick Sidibé, and different painters who would try and make sort cultural underground scenes into the subject matter of the paintings like Manet and Picasso. And then I always go back to Romare Bearden for the specific way he composes bodies, and I managed to find some really good books of his in America which helped inform what I was doing.

My earlier work would start with musicians as the subject matter, but I’ve wanted to move a little bit away from that, and developed it into any moment of life between people. So there's guys playing dominoes, and people chilling outside the factory where they work.

Are you pulling from both fiction and real life in these scenes you're creating?

Yeah, I want it to look relatable to real life, and I like realistic storytelling in films and stuff where there's the local characters that might crop up in a film. Also my Dad’s writing is quite like that where the older people he grew up around are fictionalised into something entertaining but quite nuanced real life stories.

It feels like your paintings are… auto-fictional, perhaps? And anecdote is such a great material, for both writing and art.

I love books that pull together from little stories rather than a grand narrative and I love that in films as well. I grew up with a lot of stuff like that.

I was also wondering if travelling is influencing your practice at all?

Yeah, I think in LA it was more so ‘space and time’, I wanted it to be more culturally significant than it necessarily was but definitely being in Mexico there was a massive choice of culture. I like to be a little sponge when I pull up somewhere, and get the low down of a new spot.

A lot of places I go to I've already got some idea about from films. Like Jamaica is my whole upbringing, me and my sisters were always thinking about Jamaica and we had our ideas about it. But actually going there was amazing because of the story telling from cab drivers, and a waitress we met around the first place we stayed would go really deep into a story about her family unprovoked… but I love picking things up along the way whenever I’m travelling.

I feel like you’ve got a really rich set of references that you’re pulling from, loads of different disciplines and then your paintings speak in these different tones, colour and texture, and scale feels really important, they look massive. And then I think they almost feel like your animations in that way, they feel super alive.

I think my favourite form of art is film so I wanted it to lend itself towards that medium because I haven't learnt about cameras yet. It’s a way to learn about those things through painting, and collage makes it easy because you can animate the characters by moving them round and they can settle into a still rather than a really composed idea. You can move them until they look really comfortable and dynamic. And I look at a lot of animators who would just use cut outs and still make them alive, even though the individual parts are quite rigid. I like the idea of bringing them to life after they’ve been painted.

It's got this old school sentimentality of being really manual and tangible, and I love the idea of you personally performing that camera function without having to use an actual camera.

Yeah exactly. And all the animation I love tends to be the really tactile stuff where you can see the mistakes or you can see the artist's hand in it. And the photography I like is usually quite low budget, one flash kind of thing.

It’s very humble. I think that's the kind of work I’m really enjoying at the moment, work that’s in one sense loud, but in another sense not arrogant.

Yeah, yeah I like that a lot. That's definitely the tone I like; it's not showing off too much and quite down to earth.

But it doesn't have to be because it's so exciting, it speaks for itself.

I think something I try to be conscious of in my life is that people in the street are fascinating. Even if they're not praised, all those people, I want to hear their stories. I want to interact with them and that's when I feel I’m in a good place, when I acknowledge the people in the high street who have been there longer than me.

I wonder if that has something to do with growing up with Black elders?

Definitely. That reminds me of my uncle and listening to him and my dad just chatting. My uncle will be going off on tangents…

There’s something about an older black man telling a story that's just everything!

My uncle is just outrageous. And then my mum will be the only person who will actually challenge it. They have really funny interactions.

Do you think your work wants to capture these kinds of dynamics then?

Yeah, definitely. I want it to be that kind of thing you hear from the elders. They want to give back to you, so giving credence to their story from the position of being young is very important to me.

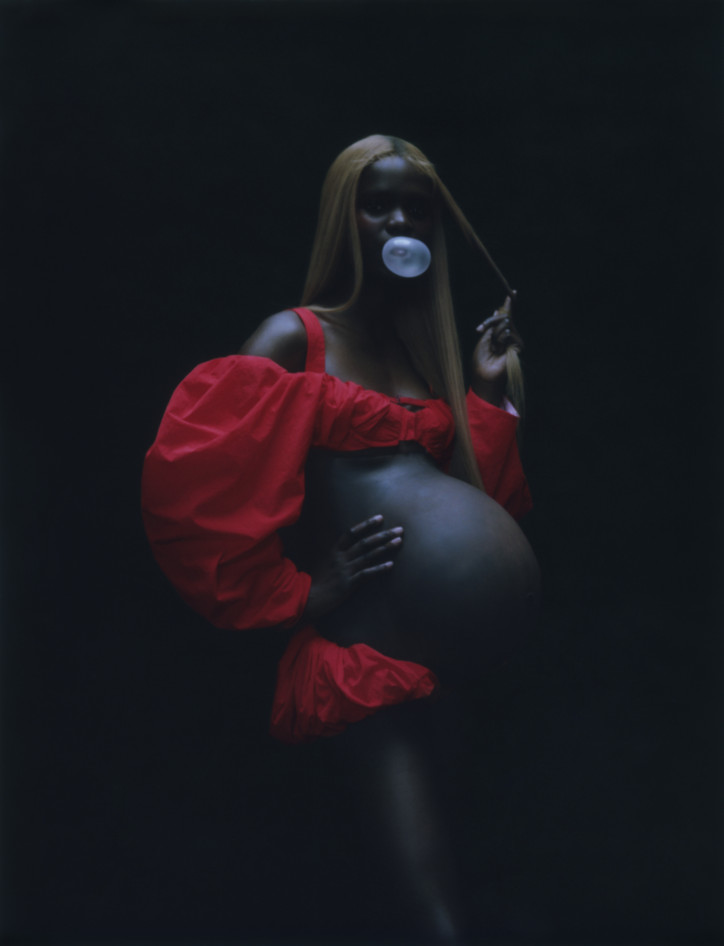

Throughout the room, each photograph unfolds a captivating story. Entranced, I find myself envisioning the vitality captured within the frames — young ballerinas’ graceful movements unfold in slow motion as they kneel down, foreheads to knees, hands rising and falling in a choreographed display. The spell is broken by distant chatter, as the room fills with animated voices and flashes that reveal my reflection in the next piece on the wall. Now observing a pregnant woman, her belly so prominent that when I focus in I see myself in it, as I contemplate the heightened appreciation for the female form. The artist's male gaze, devoid of hypersexual poses, conveys power and beauty in a unique and much-needed way.

Moses discloses that the pregnant belly in one of his works was, in fact, a prosthetic, skillfully portrayed by the model. Normally, most photographers stay away from featuring anything other than a flat stomach. For an artist to recognize the beauty of a full stomach — so much so that he actively search one out — further solidifies Gabriel Moses as a once-in-a-lifetime talent.

The exhibit, serving as a tribute to the femininity that has shaped the artist, now sparks curiosity about the evolution of his perspective and exploration of the parallels between Regina and Marsha. Reflecting on his upbringing, Moses shares, "Being raised in London, in a single-mother household with my sister, I gained immense respect for their perception of beauty. My home was a sanctuary without toxic masculinity, allowing me to see life through their lens in hues of pink. When I held that camera, I knew what I wanted to create. Naming my projects after the inspirational women in my life — Regina, the name of my studio, which in translation from Latin also means Queen, and Marsha, my hairdresser — was my tribute to their impact on my journey."

Evaluating his multifaceted career through fashion, sports, and film, we speak about the importance of diversity in the artist’s creative vision. "I create moments inspired by the past and the future,” Moses explains. “My grandmother left me with royal memories that I've fallen in love with. She was a dynamic woman, as was the generation before me. I’m going to have daughters and nieces. I have to create an environment — especially now as an artist — to ensure they see representation and produce art that allows them to grow up loving themselves. This responsibility stems from the love my mother poured into me, even creating for people I don't know. That's the beauty I see, and I won't portray anything else." Such a heartfelt reflection reveals Moses’ deep appreciation for his roots, highlighting the influence of personal experiences and family ties on his outlook. The confidence instinctively built into himself is seamlessly depicted in his works. It makes sense.

Back at the reception, Moses holds flowers and momentarily stands out; otherwise, he's blending into the crowd. His emphasis on world-building is evident as he discusses the independence he maintains in his work. Perhaps, Moses exemplifies a lesson: maybe you're not meant to do everyone’s work if there are conditions to your process. "There are no rules. I do what I want because I don't chase what's not for me. If I can't do it my way, I'll do it on my own."

Shifting the focus to his filmmaking process, we discuss the emotions he aims to evoke in his audience, noting the quiet backdrop in IJÓ and Regina, in contrast to the liberation and airy emotions in Marsha. "I'm all about feeling. I'm not the biggest on films." Moses claims. "Psychology, details, colors, tone, and movement — these elements come together naturally for me. Connecting from an audience level, I create films that resonate with how I would feel. Quite airy, beautiful, subtle…"

The discussion extends to his upcoming book, set for European drop in the first week of April, and US drop in early June. Moses reflects on the significance of physical representation in a world dominated by social media. "It's about timelessness,” he starts. “Growing up in a social media world, I still need to produce things that can be passed down. The physicality of a book offers a different experience, and I want kids to discover my work in libraries – an experience unlike seeing it on a phone. This book also comes with personal archives; images from my childhood, my family, my friends… It’s a well rounded look into the word that is around me and one that I am creating through me. "

Reflecting on his unexpected foray into fashion photography, Moses shares his perspective “Did you ever think this guy would be a fashion photographer?” “Growing up in London was a moment to express oneself. But I don't get too excited; I understand the ebb and flow of good and bad moments. They are purely fleeting moments.” Chicago, in Moses's eyes, becomes a testament to the reach of his work, exceeding expectations with its warm reception. "I had no expectations, and it's humbling to see people leave their homes to experience my work in a city my mom and I have never been to. It's a testament to how my work has traveled, and being here feels like home."

Concluding the interview, I take a personal moment with Marsha, immersing myself in the African cowboy narrative. Moses, through his masterful use of colors and imagery, challenges false narratives and showcases the rich history of African American cowboys. His distinct style, despite his youth, prompts contemplation on the control he exerts over his conditions and artistic vision.In closing, Moses emphasizes his pride in his work, inviting others to appreciate it as well. He leaves us with a parting lesson: perhaps not every task needs to align with one’s creative process. He asks us a question that gets to the heart not only of his practice, but of his philosophy: “Do you love your work, or do you just love the way you’re being received?”