Stored

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

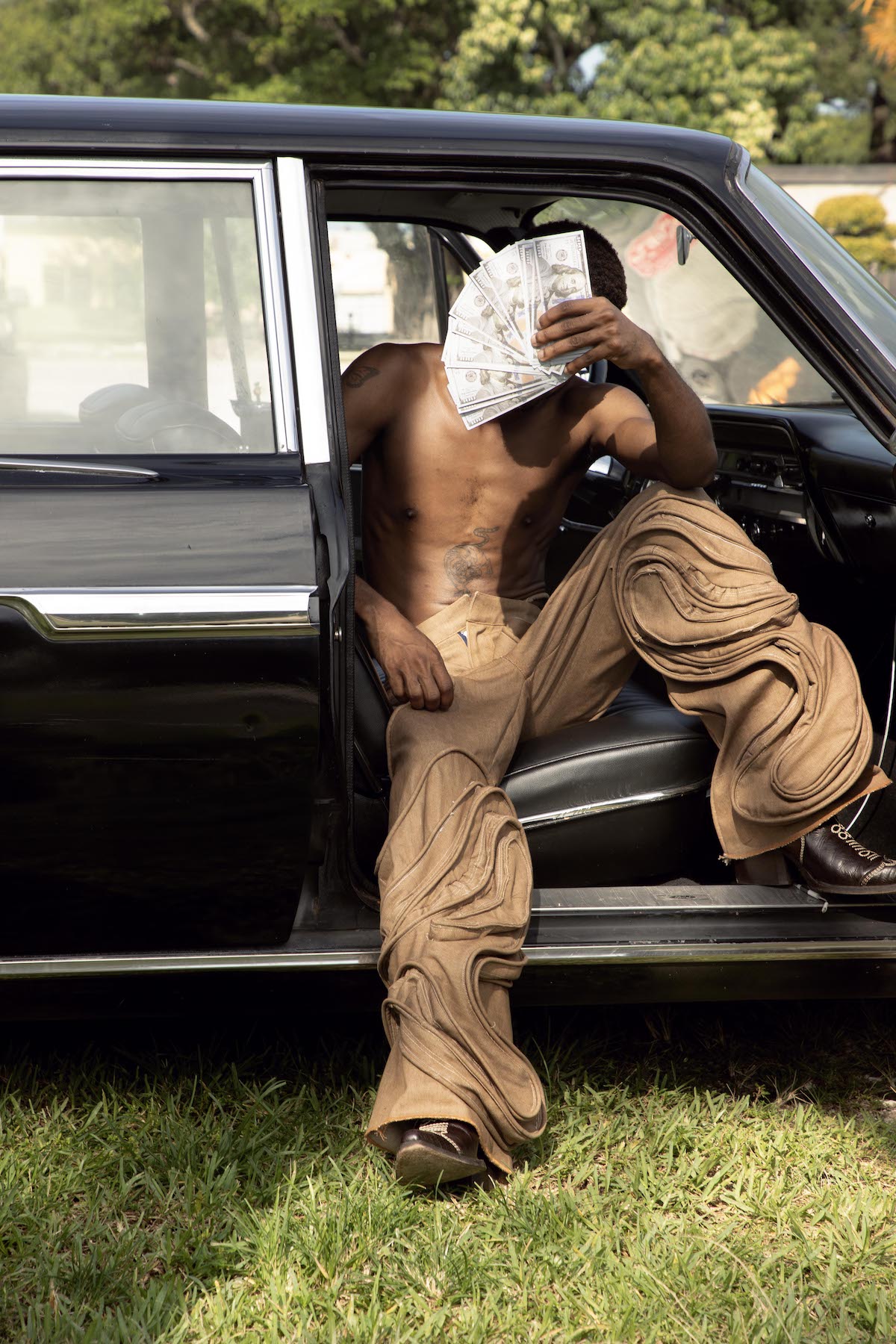

The designs themselves reimagine the potential of denim as a leading material; transforming the textile both physically and symbolically through bleaching, Baptiste simultaneously examines the storied role of denim in American identity and uses it as a site for cultural dialogue. An accompanying film created in collaboration with Jordan Blake and the Black queer collective MASISI documents the rich and vibrant beauty of Little Haiti's ceremonious spaces, alongside a series of photographs of the collection shot by Baptiste. Approaching the closing week of the exhibition at MoCADA in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, office sat down with Baptiste to discuss his creative journey and the inspirations behind Ti Maché.

Samuel Getachew— Hi Daveed!

Daveed Baptiste— Hi! How are you?

SG— I’m great, congrats on the show!

DB— Thank you, thank you!

SG— You combine fashion and photo in the exhibit in really interesting ways. Where did your creative journey start for you? Which medium came first?

DB— My first medium was definitely photography. I started shooting in middle school, I want to say like seventh or sixth grade. At the time, I was living in Miami, Florida, not Miami specifically, that's that's like, you know, my first home. And we were at this after school program at MoCA [Museum of Contemporary Art], and they had a teen program, similar to how the Brooklyn Museum has their teen program.They had different classes every single day, and I really came into myself in those classes.You know, you're young, you're discovering yourself through a creative medium. And for me, that was definitely photography.

At the time, I feel like images weren't as accessible as they are now — we had smartphones, but the quality of the iPhones weren't that great. So it was really about the point and shoe that your grandparents might still own. And if you had a DSLR camera, I mean, that meant you really had money to spend on a camera. So I discovered images that way. And I would say fashion kind of came afterwards.

I felt like photography was more natural for me, it kind of felt very spiritual. Not in the moment, but now that I have the language for it. And then design was this learned thing, that I'm very passionate about and I love, but I just have a different relationship to it than I do with photography. And people often like to ask, “if you had to choose one,” and I'm like, I’m not choosing.

SG— I love that! Was there a moment for you with photography where it went from this cool thing that you're getting to do in this program to something that you saw yourself taking seriously? When did you start considering yourself a photographer?

DB— I think when I moved to New York. When I was like 15, 16, I was going to house parties in Miami – I loved taking my camera to the house parties, and photographing people. I loved watching people's reactions to seeing an image of themselves at an event or at their best moment, whether that's like their wedding day or baby shower. But when I moved to New York, I started seeing really young people, like kids who are 19, 21, 23, shooting campaigns, shooting things for huge brands, shooting for big magazines and editorials. That’s when I realized, this is a real thing.

SG— Yeah, totally. I definitely know that feeling, like you see it, and then it kind of lights a fire under you. How did you start working with fashion and textiles? Did that begin when you started going to Parsons?

DB— When I was in Miami, I went to a school called Design and Architecture Senior High School, or DASH. It’s a very special school, a lot of amazing people have come out from that school who are now practicing creatives, in all different fields. They had a fashion design program.

It's a magnet school, which is technically like a public school, but you had to audition to get in. Most kids got in their freshman year, but they rejected me three times. I had like, really bad grades. I knew I was just as good as all those kids in the school, if not better, but I wasn't the full package. I was a kid from the hood, who just was not very well behaved with shitty grades.

We had a teacher named Rosemary Pringle, and I learned how to sew in her class as a junior. At the time I didn't really feel like I belonged in fashion. And I remember, this was around the peak of Hood By Air, so I think kids my age across America, and across the world, were watching New York culture, watching Shayne [Oliver], and that that was special. It was the first time I had seen someone Black in fashion like that.

SG— With this show, were you thinking about the garments first, or the images first? Or did they both come to you at the same time?

DB— I was thinking about both simultaneously. When I create garments and pieces, I'm also imagining the world that it lives in, visually and culturally, its presence in a space. When I was creating the collection, it was material first. It's an eight look collection, and most of the pieces are in denim.

Denim really speaks to so many things — culturally, I think spiritually, for a lot of people. I feel like it's the people's fabric. It's the people's material. There are so many young folks who start designing, and denim is their first choice. It's one of the few textiles that can transform so many different times: it could be etched, it could be printed on top of, you can put a puff print on there, it could be laser cut, there’s all the different washes that exist, all the treatments, it ages over time.

Before I actually started doing photography, I was drawing with my brother. Now it feels like I've been drawing with denim – the actual material, it feels like you're painting with it, like you're drawing with it. I love the way it wears. I love the different faces that it has over time, and how you can control them depending on what you do at the factory.

I'm a designer who approaches materials first, and I let the materials lead the rest of the design, lead what the silhouette’s going to be. I really wanted to push what denim could look like, what new washes we could invent. I feel like every decade and every generation does their thing with denim, and we keep reinventing and reimagining it, so this was me trying to scratch the surface of what this world would look like for me.

SG— Totally, it’s interesting to see how over time, when fashion trends cycle through, it's not that denim cycles in or out, but the cut of the denim changes, or the wash of the denim changes. But it's still always there.

Typically the way that people view a designer's work is through a fashion show – so you're seeing the garment in passing, in one quick moment on a model, and it's this very ephemeral thing. What do you think the effect is of having the garments in the show, static, alongside their own images, as opposed to just having people view just the images alone or just the garments alone in a passing moment?

DB— I wanted to give people an immersive experience that they kind of had control of, in the sense that you can decide when you come into the space – versus on a runway, the moment is fleeting. I think an exhibition is so much more liberating.

Fashion has always been exclusive in so many ways. By presenting the garments and the exhibition for two months now, I was able to reach so many people: from folks who are in highbrow culture, to folks who are in Fort Greene walking down the block, from people who saw on Instagram, they all really got to go and experience the work. I wanted that freedom and liberty for the work in itself, for it to be able to truly breathe. I grew up in the art space, in museums and galleries. As much as the fashion community is my people, my village is the art kids. So I wanted to bring a fashion energy, but into an art setting. I got to tell the story of Haiti and the Caribbean, I got to tell a story about migration, I got to have very specific details in that exhibition that you wouldn’t be able to get through a runway show, or the way that other institutions have done retrospectives or fashion exhibits. And I want to shout-out Amy Andrieux, the curator at MoCADA. She worked day and night with the museum and with me to elevate it to the highest level possible.

I really, really love working in that museum space and I want to continue to. I’m also seeing my contemporaries and some of my peers enter that space. Taofeek [Abijako] from Head of State had an installation at Strada Gallery last fashion week. People are slowly entering that space. It's very exciting. It's more cost efficient. It's more democratic. It can access more people.

SG— You went back to Miami to shoot the collection, which I loved. Could you tell me about that decision, and the role that the city played in influencing the collection?

DB— I came from Haiti at six and moved to Miami with my family, where I grew up. That’s home. I wasn't even doing it, like, in a “I'm here to honor my community” type of way. I just really fucking love Miami, and I love what the young folks are doing, and I love the neighborhood I come from. I come from Little Haiti, and North Miami. I love the rich Caribbean culture that's there, specifically the Haitian community.

I knew I wanted to work with MASISI collective. In New York, we have so many Black queer and trans collectives – as much as we're still the minority here, the city has an influx of really awesome spaces that are being built for our community. But Miami has so few, specifically for Black queer and trans folks, and MASISI is so special.

Akia, the founder of MASISI and also another fellow Haitian, produced the shoot and they casted models for it. So they were pulling from their collective, or pulling from their network of creatives that are cultivating culture in the 305. They were also scouting the locations. And a lot of those places that we were shooting at are places or environments that are pivotal to Little Haiti – spaces that may not exist in 10 years, five years, maybe even one year. Little Haiti is one of the most rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods, in Florida and in the country. The land that Little Haiti sits on is super high up above sea level, and Miami is drowning, so there's been a huge push to purchase the real estate there and push people out of the neighborhood.

Like I said, when I'm making these decisions, I'm not doing it for all of these reasons, I'm not a hero in that way – I'm doing it because I really fuck with my neighborhood. But here's the context of what's happening. For me, it was really about bringing Black Miami culture to a broader audience. When it comes to the music scene, we have cool people that came out of the 305 who get a global audience – you know, we love the City Girls, we love Trina. But then, when it comes to fashion, like designers and painters and photographers and film and actual images from North Miami, that doesn't make its way into the mainstream.

SG— I love that. Could you tell me about the film you made with MASISI? And what role film has in your practice, as a new medium for you?

DB— Film is very, very new for me, like yesterday new. We shot with freaking legendary, amazing director, filmmaker and photographer Jordan Blake. They're like a triple threat, which I love.

We met in New York, we’re friends and he knew about the project. So many friends knew about what I was doing and saw the work progress over the years. And I was like, “Yo, can you please film this,” and Jordan was down from day one. There was something really special about this person I had only met a year ago, trusting in my vision and loving what I do. And also our aesthetics are very different, but similar in the sense that we want to portray Black people in the most beautiful way through our own aesthetic decisions.

He didn't ask questions. We had like literally one meeting. And he stayed with me in Miami for a whole week and we filmed. We have all of the visuals that I shot, but then Jordan brought an extra layer of storytelling with the filmmaking with these beautiful cinematic images and stills. When I saw the film, I was like, Holy shit, I can't believe you just shot Little Haiti with this sexy ass camera. Cutting and editing was a collaborative process with Jordan, myself and my family. My little sister just moved from Haiti a year ago. She's 21, and I love her perspective. Having her help me with sound design, that was really sweet.

Ti Maché is on view at MoCADA Culture Lab at 80 Hanson Place, Brooklyn NY until December 30, 2023.

“Find the beginning,” follows Wilson’s wording. Joseph Cochran’s beginning is his lowest point. After he and his shared Bed-Stuy apartment fell victim to a gunpoint robbery in 2011, Cochran was “on nothing and doing absolutely nothing with [his] life.” A friend gave him a camera, no strings attached, with no strings to pull either, and so he took off, leaving the pack to chase a different path.

A decade later, the man returned an artist; a photographer; a researcher, but above all, a storyteller. In its horn of plenty, Forays, Frontiers, and Flags — spanning 12 years —is a comprehensive display of Cochran’s footsteps across the globe. comprehends Cochran’s footsteps across the globe. Throughout his escapes, he continuously found himself in places penetrated by systematic instability, censorship, or challenging change. Amongst the events are China’s resurgence to superpower, Hong Kong’s fight for freedom, the migration crisis in the Mediterranean, and the ever-so-chilling effects of the pandemic — none of which were exposed but experienced through Cochran’s patient explorations. Thus, his work allows the viewers to do the same — not just to look but to interact.

“Where am I now? Are those who live here violent and cruel? Or are they kind to strangers, folks who fear the gods?” continues Homer’s poem, and thus Cochran’s practice. His sensitivity spots the nuances, focuses on the impacts, zooms in on understanding, and flashes the truth. He blurs the boundaries between diary and documentary.

In times when images are exhausted everywhere and oftentimes all too empty, while both the trust and credibility for institutional media continually decrease, Cochran's images stand out. They place themselves at a great distance from the flat and from the false, and by doing so, also archive a sincere sense of urgency.

Piccolo Mamuthone, 2019. Reality Show, 2018.

Vilda Krog — When you first picked up a camera, you were "not thinking about art.” Is there a specific space, sequence or image that you could tie the shift to — at what point did the medium turn into the messenger?

Joseph Cochran II— You know when a force is pushing you in one direction? And you ignore it and ignore it some more... You keep ignoring it up until that point when the signs become so prominent that you’re no longer able to run away from it. That’s it.

I was hanging out in Philly a lot, meeting plenty of people who were making pictures, doing creative work. I didn’t have an outlet of my own at that point, and I was constantly trying to find one for myself but kept hitting roadblocks. I pursued writing, creative management, but I never felt truly immersed until one morning after a graveyard shift at the casino I was then working at.

I got home at seven in the morning and wasn’t tired, so I finally picked up that camera-turned-dust-collector and started playing with it. I showed the results to some of my friends, and pretty soon it all made sense — that this had been my medium all along.

You left writing, amongst other mediums, behind?

I still write a lot, mostly for myself though. The reason why I stopped pursuing it professionally was because once I began to use the camera I realized that the lens is just a much stronger way of writing for me. When I looked at the work of some of my early influences, Diane Arbus or Gary Winogrand, I thought, “Wow, these people are doing what I’ve wanted to do in text, through photos.”

I wouldn’t say that I gave up writing, rather that I write in images now.

Listening to you this past Friday, you mentioned your dislike for certain words or used phrases like 'for lack of a better term,' demonstrating the limitations of language as a tool for expression. Have you come across anything a camera can’t explain?

The only element that holds back the camera is the user of the tool, otherwise, it’s completely limitless in terms of expression. There's a quote that I think about by Wolfgang Tillman, perhaps I’m paraphrasing but it goes something like “I can't explain what images do to me.” That’s exactly how I feel about photography.

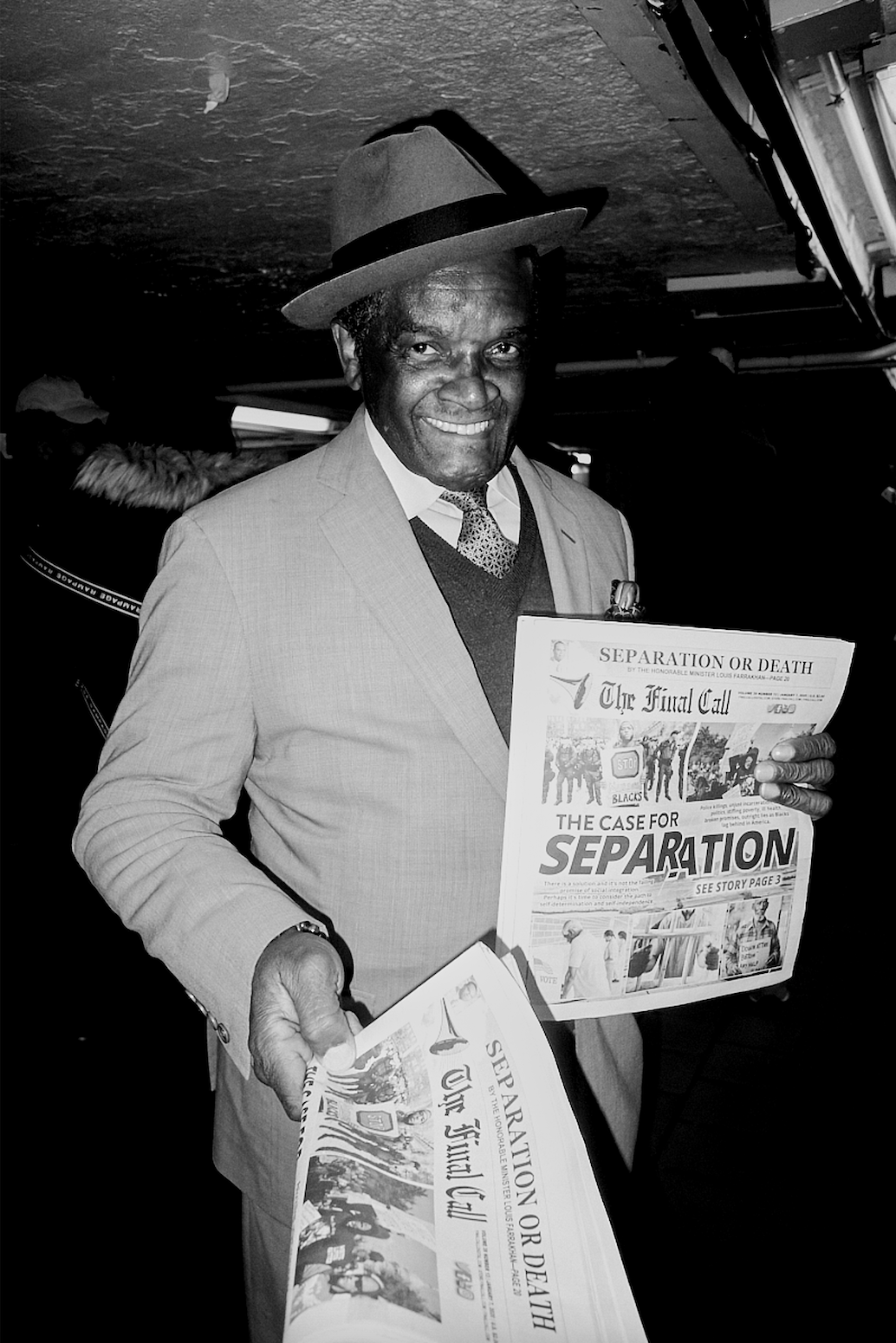

Untitled (April), 2021. The Case for Separation, 2019. Things Fall Apart, 2016.

There are multiple shoutouts when you speak about your work. Yet what I found interesting is that none of the names you mention — Sontag, Baldwin, Debord — are photographers or image-makers. Is it an active choice to pull inspiration and references outside of the visual word? How does that open up avenues in your practice?

I could probably name 30 photographers off the top of my head that have influenced me, and I'll get excited while doing it, but that doesn't mean that I look to them for inspiration on project works. Most of my references are literary because my process comes from a literary space — philosophy, anthropology, and a little bit of fiction as well.

I'm really big on Russian 19th-century literature, and I've been reading philosophy since I was a kid. My grandmother would read me the Iliad and Odyssey, all those Greek and African myths, about the French Revolution, you name it — and I would swallow it as if it was fiction, only to be told that it all had actually happened, that what we were reading was history.

When you look at an artist like Baldwin or Sontag, these people have left behind a Codex as to how to unlock society. It’s coming back to the idea about how to understand contemporary society, taking something that already exists and just changing it by 3% and thereby turning it into something completely different; it’s directly connected to sampling, which correlates to what Virgil Abloh did with Nike, what Duchamp did to art. It’s an interesting avenue, where the whole power sits in the references; the same could be applied to fashion — it’s not about who has access to the finest fabrics, but who has access to the finest books. It all boils down to those who fucking read.

To me, the game is about figuring out — through text, through image research, or through a combination of things — where and how you fit in.

Through this major project of yours, have you been able to discover where you fit in?

I’ve discovered how deeply I care about humanity and how I care about the whole of it more so than the micro or the exclusive. I am interested in the spectrum of society, the good, the bad, and the ugly, and through the camera, I can empathize and relate to it all. In my formative years, I thought that I didn’t fit anywhere, that I was an anomaly in a sea of normalcy. Today I recognize this as a positive, but it certainly did not feel this way in the beginning.

My experience as an at-risk youth in New York City, whisked away from my family made me think I wasn’t loved, wasn’t wanted. It took living on four different continents, falling in love, falling out of love, immigration — all of the substantial experiences I encountered over the years documented in this book to realize that all the love I ever needed was provided — it was in me and always around me, I just needed to open my eyes.

My father never had the opportunity to leave New York unless it was in chains, my mother and grandmother never had moments of respite in their lives, and in my grandmother's case, she never will. They were born into an unfortunate cycle of government-sanctioned domestic terrorism. This work revealed to me that I am the hope of my family, I embody the wishes of my ancestors for us to be more than the cards we have been dealt.

Perhaps the biggest discovery for me, is that I will never stop making this work — it is what liberated me and gave me my mission — to witness humanity in its entirety, telling not only my story, my mythology, but those of my family, and others who trust me with theirs. Whether my friends or family, refugees, my Muslim brothers and sisters, and others I’ve crossed my path with. I saw them and their stories as important, and integral to what will be the history of our time. I’ll honor them today and tomorrow, and after the day I’m gone.

Home for Migrants, Nuoro, 2018. Uptown, 2019.

Listen to the full conversation from the release at Printed Matter, supported by Dirty Magazine and Uncensored New York, here.

“We had lots of pets and my grandma always made wild sculptures in every room even though she never called them sculptures. A giant parrot cage with a light-up goose and suspended engraved ostrich eggs with chili pepper lights and action figures enacting wild scenes would greet you when you opened the front door.” Beerman’s grandma would then craft terrariums filled with cake decorations, various mosses, disco lights, toys, a cut out of Albert Einstein acting out scenes from movies and from stories she would write. “They were always playing funk music and classical music and also the radio. We were always talking to each other.”

Moving onto her inspirations, her body of work encompasses a wealth of contrasting elements that juxtapose subtle and punchy denotations into vibrant canvases, giving life to works that have an abstract feel with a mixed media edge to match. “I’m inspired by all sorts of things but mostly desperation, survival and connection. Colors and textures. Loss, grief, humor. Just missing the mark. Hugs. Costumes. Invisible things. Holding hands. Love and intimacy. Shyness.” Beerman’s oeuvre features strokes that range from being extremely thin to exceedingly bold. On that note, she tries to justify the decision-making steps of her creative process as an accumulation of things that build up differently over time. “Spontaneity and slowness play different roles. I hope I don’t have to justify anything,” she remarks.

In her recent exhibit, titled Paintings — her third solo show at Kapp Kapp gallery, on view until January 6 at 86 Walker St in New York — Beerman teases the boundaries of what typically defines painting, incorporating a plethora of materials stemming from what surrounds her in daily life, such as cat toys, glitter, receipts, spare umbrella parts, coat racks, and clothing.

On the challenges, she speaks with unguarded honesty. “I think that might be all I do as a painter, encounter challenges I mean. Then happy accidents. Formal, pictorial, technical — all as challenging as ever. Every time I start a painting it feels like I’ve never painted before in my life and I’m starting from scratch.” This leads me to ask what techniques she normally works with. “I always work on the floor,” she says. “I like gravity and anti-gravity. Sometimes eventually paintings make their way on to the wall. Always developing many surfaces at once, like layers and accumulation. Sometimes I carry around paintings for years and they breathe and fester. What is a beautiful and gentle word for fester? Grow? Comes with pain and awkwardness all the same. There’s air and sometimes seamlessness in space there too."

Veering between directness and ambiguity, we wrap up by unpacking what she’d like people to take away from her work. “Permission to be disjunctive, in love, inappropriate, take naps, sing really loud, hug your mom, be wrong, scratch your itches, grow out your armpit hair, learn a new language, or just walk away — hopefully, though not that last one.”