The Strange Magic of Ariel Pink

The retrospective series also includes previously unreleased material and focuses on the years when Pink recorded as Ariel Pink’s Haunted Graffiti (1999-2004). It was during this prolific period that Pink’s immense fecundity of experimental ideas took shape, oscillating between 70s and 80s AM-radio pop and proto-punk to a kaleidoscope of deranged experimental sounds and home-recordings.

“I’ve always thought of myself as sort of being on the outside of linear progress,” shares Ariel Pink on the phone from L.A. where he spoke with office about the archive series. An avant-garde master of sonic invention, Pink has produced a legacy of work spanning 20 years, all the while defying pop conventions and hugely influencing a generation of artists who have come to embrace his idiosyncrasy. Pink has always followed his instinct, his creative stream coming from a place where Siren calls echo from another orbit. While his work may not always be easily palatable, it’s certainly unforgettable. And to lose oneself in the space of Pink’s archives is a submission to his strange magic.

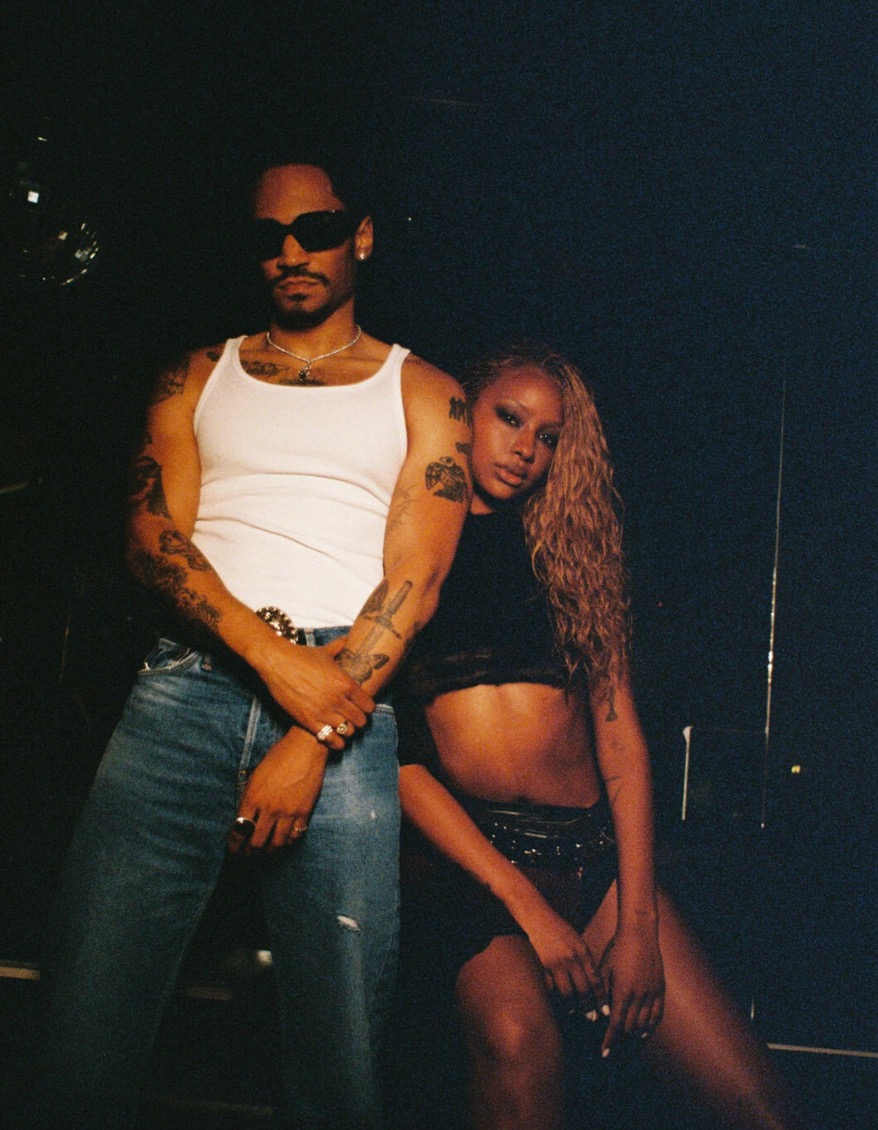

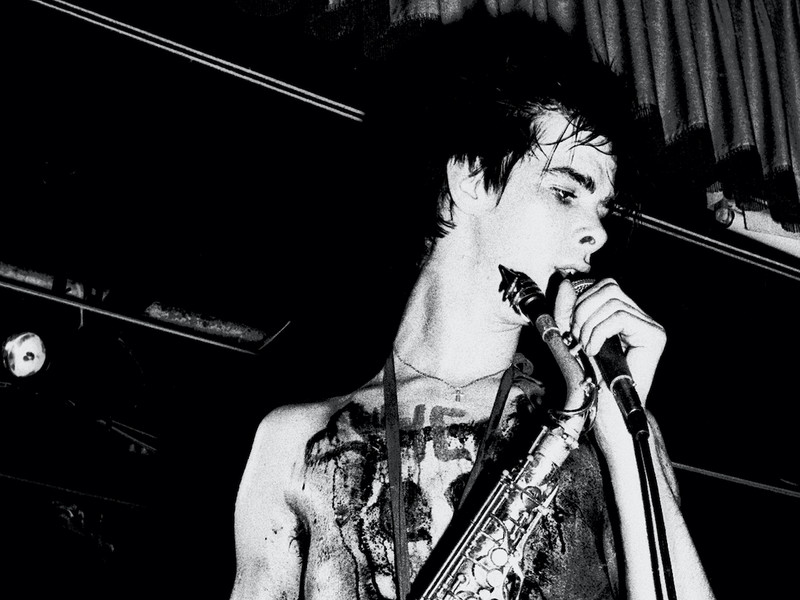

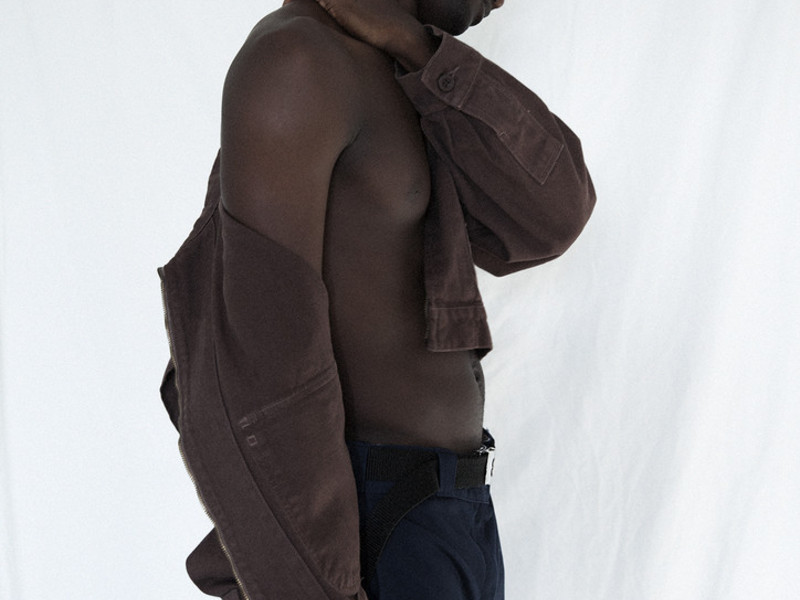

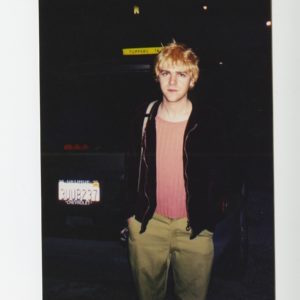

Left image by Patrick Kwon; Right image by Alisa Daniels

How has your day been?

To be honest, I just got up but it’s bound to be glorious.

I remember seeing you perform at Hollywood Forever Cemetery a few years ago, or forever ago…

Yeah, in 2013 I think.

Let’s go back in time and rewind to when you recorded The Doldrums in ‘99. It’s remained a deranged masterpiece—did you have a specific audience in mind when you first recorded this, was there anything dictating your direction, or was it pure freedom?

It was pure single-minded freedom. There was no audience in mind at all. It was a declaration of independence of sorts and I was trying to make an alienated cry for help or something like that. Something that nobody else would respond to, something that actually would put me in a corner and leave me there alone.

Do you feel you’ve carried that sense of independence and freedom with you throughout your career?

Yeah, I mean I don’t think I’ve sold out. I don’t think that I’ve had to compromise too many of my principles. I’ve gotten more love and more attention, I’m not as alienated as I used to be but I’m still kind of alienated these days [laughs].

Your work has been categorized across the board. It’s been described as everything from hypnogogic to dream pop and avant-garde. As the master of your musical world, how would you describe your sound, especially during the Haunted Graffiti years?

I didn’t call it anything really, acid-pop or something like that. I thought of it as sort of classic rock ‘n roll the same way that Throbbing Gristle might consider themselves classic rock ‘n roll. I think I called myself back at the time “avant-garde experimental.” I never thought of it as anything other than experimental music, kind of like pretend music - pretend pop music or something like that. It was just a fake out - it wasn’t like a joke, it was something that I took very seriously but I thought of myself as a deranged composer. I don’t know, it’s definitely not lo-fi.

You mention experimental. There’s an interview where you express liking physics and science, which stood out because this makes me think of invention and experimentation—do you think you bring a bit of a mad scientist approach to your creative process?

I definitely have my own way of relating to music, playing with it and having my own voice. I don’t question the process. I’ve been doing it long enough now that I feel it’s like an extra arm, you know. It’s much more to do with the way that I record, the way that I express myself on multi-tracks. It’s also the way I play music in the live sense, but there’s improving and there’s just how you plan these things out subconsciously and how you go through the motions. If people want me to produce their record, I will give them what I do. If they want those results and they wanna know how I do it, they can watch me do it and voila [laughs]. It’s all about the ears, it’s got nothing to do with the gear - it’s just my ears, my sensibility that’s unique melodically and timbre-wise.

I’m much more of an Edison kind of guy than I am a Tesla, guy you know. I’m all about trying things out a hundred billion times and then making dozens and dozens of mixes that barely make the cut, or none of them make the cut. I just keep doing them over and over again and then finally I have a mix that is to my liking enough that I basically call it a day and there’s the patent on the lightbulb. That’s it. What was it, “ninety-nine percent perspiration, one percent inspiration.”

Through the perspiration you’ve created quite a body of work spanning 20 years. How did it feel to revisit these albums?

It was great. I mean, I had somebody else do it with me because it’s something I dread doing on my own at this point. My buddy Paul Millar was in charge of artistically cataloguing and going into my bank of tapes and finding the source mix, the original mix that I laid down for everything. He digitized everything. I had to give him carte blanche into my bins and he basically took it upon himself to catalogue that stuff, digitizing the actual sessions which had never been done. We ended up remixing them and getting them close to what they were originally on the records. It’s kind of a boring explanation and boring long process but it was a pretty enlightening experience to hear just how finished these things were to begin with and I don’t know how I did it.

Are there any tracks you found yourself enjoying even more now than when you first recorded them?

I never really enjoyed them to begin with. I don’t think I had enough objectivity to appreciate them, which is why I barreled through them—I got them to states that were just passable enough for me to move on.

How long did it take to go through everything and remaster?

We carved out a few visits with Paul, 10 day visits at a time, every day going through stuff. We did it, it was a job and we committed ourselves to it. A lot of the stuff I’m pretty embarrassed about. There’s a lot that’s not on the records that I get to share for the first time. A lot of it is embarrassing too, a lot of it is of questionable quality, just exposing myself in the most vulnerable way. It was great to have somebody else there to acknowledge that these things happened and that they exist.

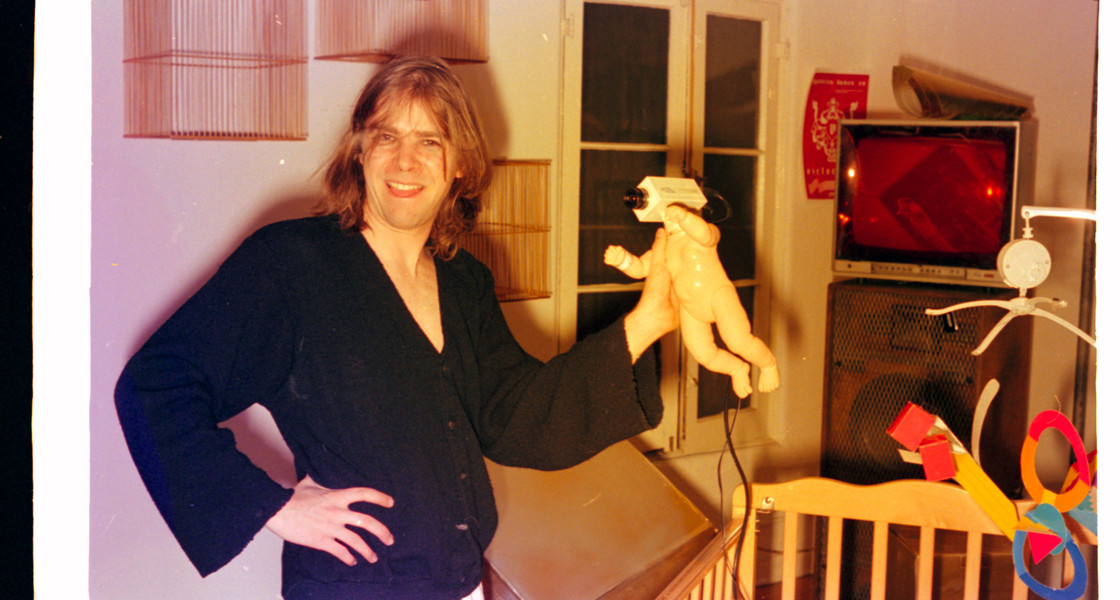

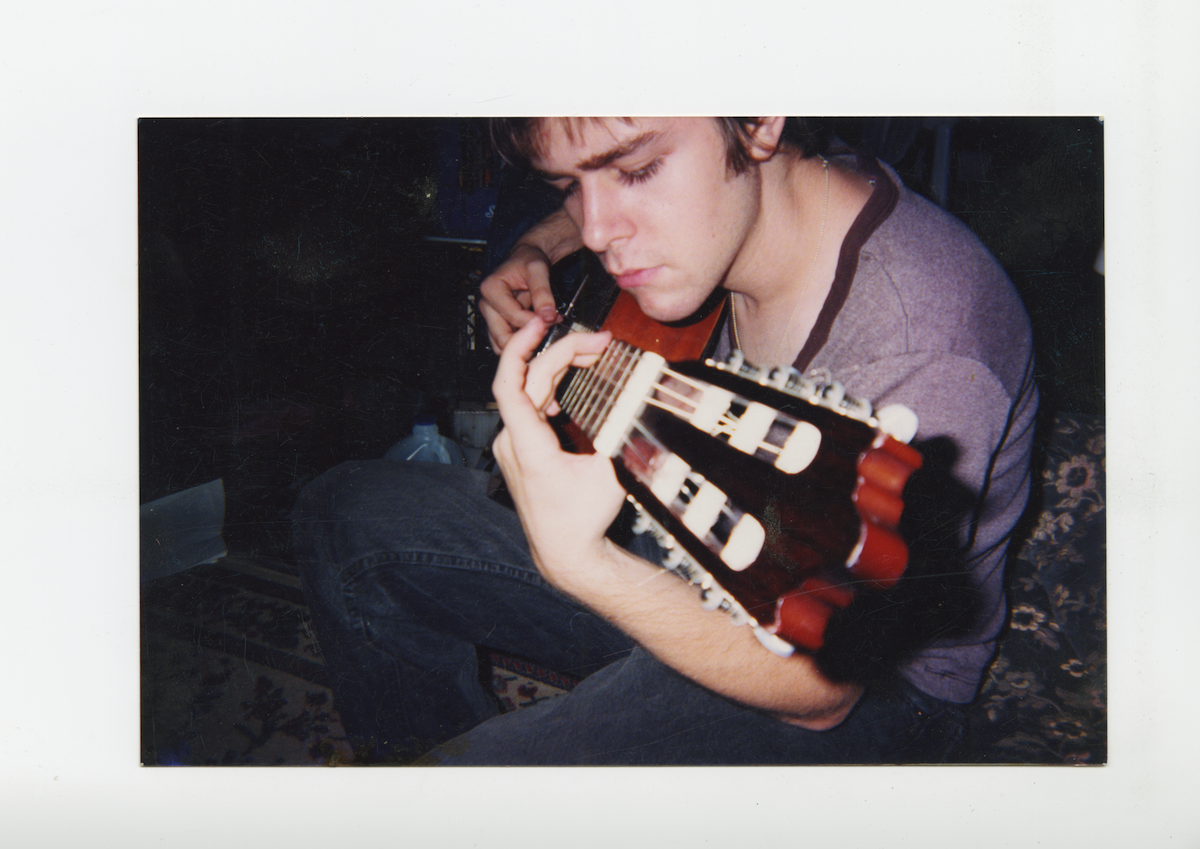

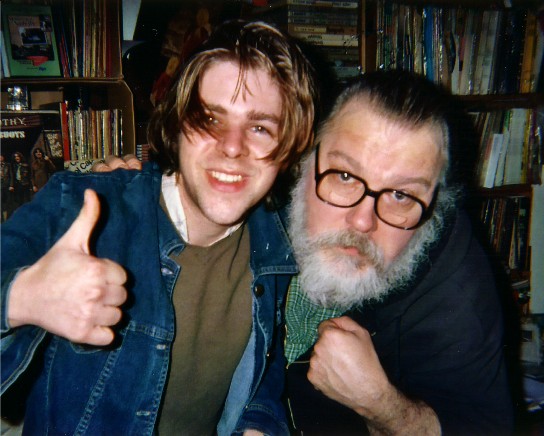

Left image by R. Stevie Moore; Right image by Alisa Daniels

What do you think Paul brought to the process that you wouldn’t have been able to do on your own?

It’s hard to qualify. He brought his own sensibility, he kept the integrity of the thing. I would have liked nothing more than to start from scratch and remix everything, make a new record, replace things that were mistakes and all that kind of stuff. He was insistent on actually keeping the records the way they were and trying to find the source mixes. I don’t know if it was laziness or just a sense of love for the records that they were, and I think we struck up this compromise too because there are certain things that were never really good enough to begin with. We spent a lot of time adjusting levels digitally and fine tuning things so that they sounded very close to how they were intended to sound, which was great but for the most part I saw him as reining me in and keeping track of the fact that these were record reissues. He was a fan of those records himself so he was very adamant about it. I appreciate that that was his mindset and he kept it very pure and very good.

So far in your musical journey, what would you say you’re the most proud of?

I’m proud that I did it. I don’t really spend too much time these days wondering whether it’s all for nothing. Those years I was kind of determined to do something that for all intents and purposes had no audience and didn’t really get much support or I didn’t have very many friends up until I was 26 or 27. So I’m proud that it paid off and that I could sort of do a little victory lap. The sort of satisfaction from that is also weaned in the time. I’m much more consigned to the fact I’m just basically trying to stay in the game. I’m glad that there’s a sizable audience that’s actively being turned on to me. I’ve been very lucky to have people tout their love for me that are much more well-known than I, so they kind of keep me in circulation. I’m proud that I never really strove to make it in any kind of real industry sense, but that’s allowed me to be humble and stay more or less low-key and not too dragged into the cutthroat world of competitive beasts and all that stuff. I don’t really participate in any of that. I don’t have a manager or anything like that either.

You seem to genuinely follow whatever your creative curiosities are. What are you most excited for next—what should we expect from you?

I’m not quite done yet. I always end up surprising myself. I’m always in retirement, I’m always feeling like I’ve written my last song. As long as I block the world out it’s fine. I mean it’s just a basic stream that comes in and dictates what I do musically. It’s very, very narrow bandwidth. It’s like a fucking cartoon – it’s just a melody and it’s a rhythm and it basically just comes to me as long as I do that thing which is pretty much what I’ve been doing the whole time. I really don’t try that many new things out, I just basically have this one expression, it’s a singular thing. I’ve been doing that over and over again. I’ve always thought of myself as being on the outside of linear progress. I’m essentially on a parallel axis of just actually going sideways. I exist on this other realm apart from everybody else, different values and a different value system that’s not based on our western utopian progressive ideals or anything like that. There’s no change, there’s this mundane and very specific focused stream that’s extending - it’s going horizontally sideways; not going up and down. I don’t know how to explain it.