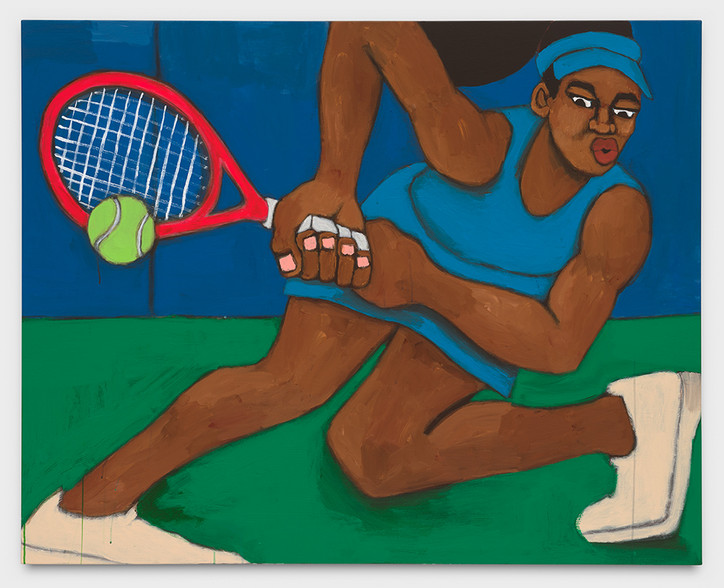

Gal Schindler, Wishing Well, 2024. Courtesy of the artist.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Stay informed on our latest news!

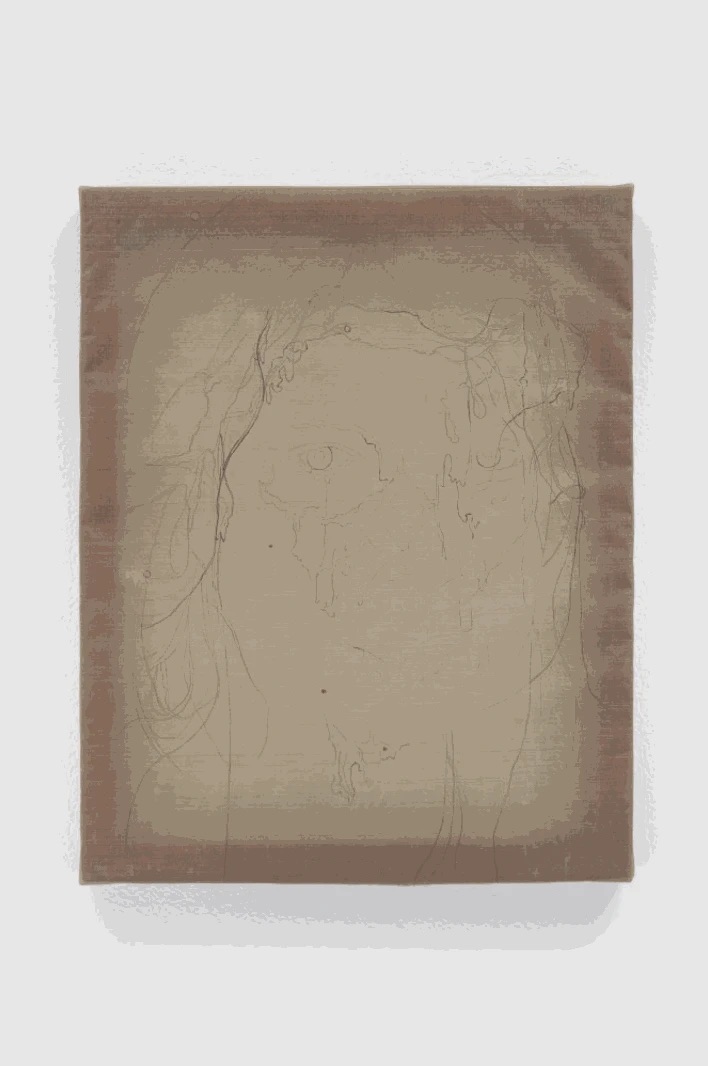

Gal Schindler, Wishing Well, 2024. Courtesy of the artist.

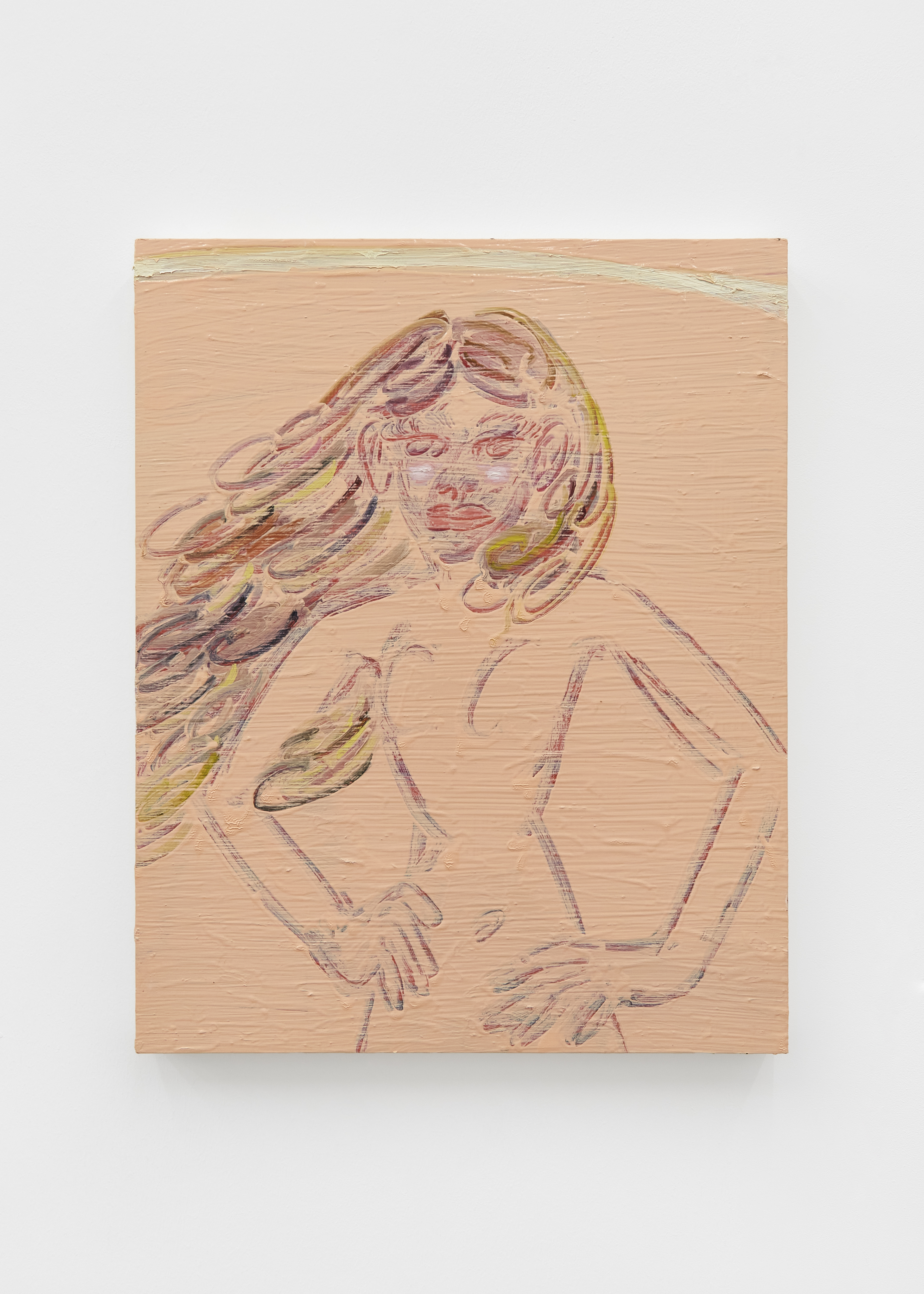

Raised on the work of de Kooning, Lee Krasner and Milton Avery, Schindler’s work exudes a sense of fluidity and ambiguity. Further citing influences ranging from old-style Disney characters and antique botanical wallpaper, the artist combines a charming illustrative style with gestural strokes and a unique scratching technique to depict figures reclining languidly leaning in and against their pastel backdrops, merging into one indecipherable composition.

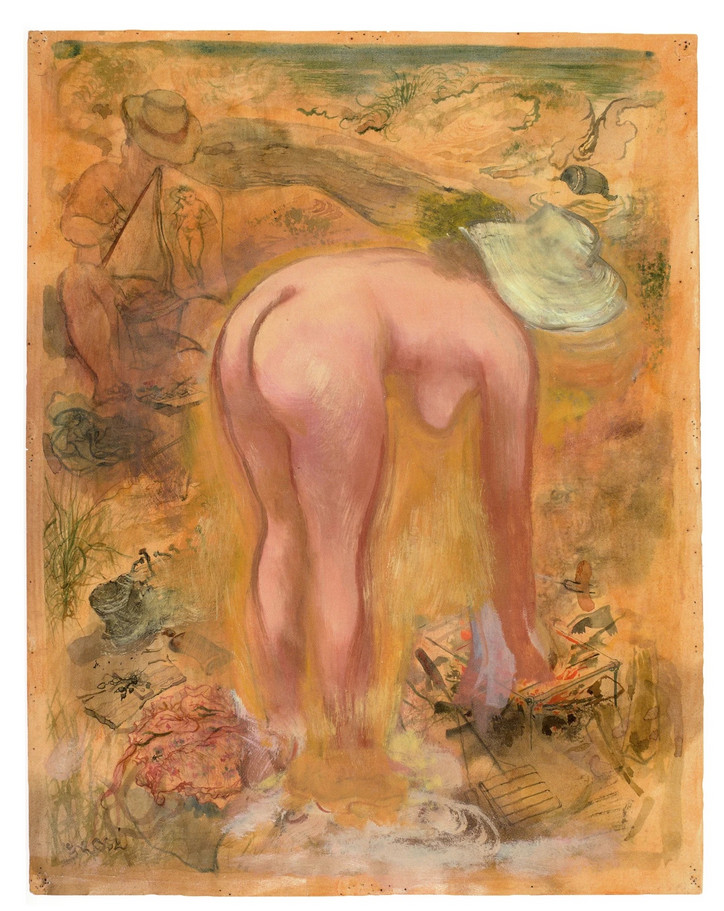

Gal Schindler, Fire Fountain, In the Meantime, 2024. Courtesy of the artist.

At the heart of Schindler's practice lies an exploration of the human form. Her nudes serve as conduits for a multitude of emotions, embodying the fragility and mutability of the human, and particularly female, experience. Further drawing on influences from her childhood, the artist references intricately depicted anatomical drawings, her loose figures and strokes blurring the boundaries between flesh and canvas.

Undoubtedly spring-like in their palette, Schindler’s works are both optimistic and uplifting, with the artist referencing themes of renewal, regeneration and growth in her playful alternatives to traditional nudes depicted under a male gaze. There’s a sense of performativity, appealing to both a female and a younger gaze by creating fluid figures that defy categorization. Schindler’s paintings are sweet without being saccharine and sensual without being overtly sexual, instead, they occupy a liminal space between categories, appealing to anyone who may be a little ground down by moody palettes and sterile compositions. The transitory nature of Schindler’s composition speaks to the flux of the human form and an inability to contain and categorize the human form.

Gal Schindler, Live the Questions Now, Paint the Rain, 2024. Courtesy of the artist.

Gal Schindler, Crystal Clear, A Promise, 2024. Courtesy of the artist.

Wishing Well is a playful collection of fairy-tale figures that lean between sensual characters and traditional forms, with the transitory nature of the compositions creating a sense of impermanence that comes from the artist's unique technique of scratching into wet paint to create transitory forms. Schindler's works occupy a realm between landscape and figuration, where bodies float in a nebulous non-space. Beginning with instinctual colour planes, the artist overlays rapid structural lines, leaving behind traces of gesture and memory. The resulting figures blend seamlessly with their visual surroundings, their forms emerging from the depths of the canvas like reflections on still water, calling to mind the “Wishing Well’ in question. Life ripples on still water, Schindler’s figures remain distorted and alluring, half-emerging and half-hidden, they occupy somewhere between imagination and reality.

Wishing Well is on view at Ginny on Frederick, 99 Charterhouse St, Barbican, London EC1M 6HR, United Kingdom until May 24th, 2024.

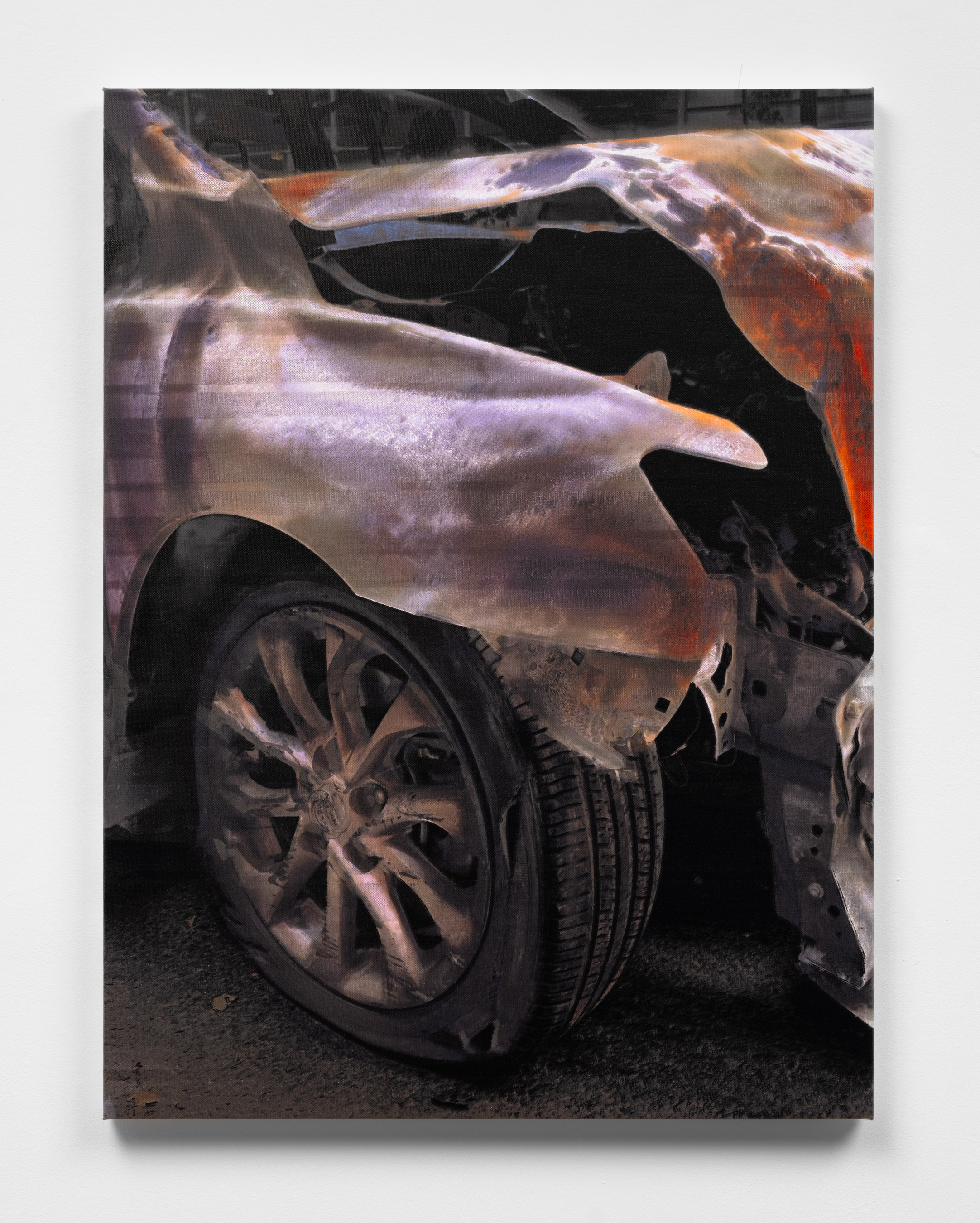

Thomas Blair, Crashed Car (Flat)

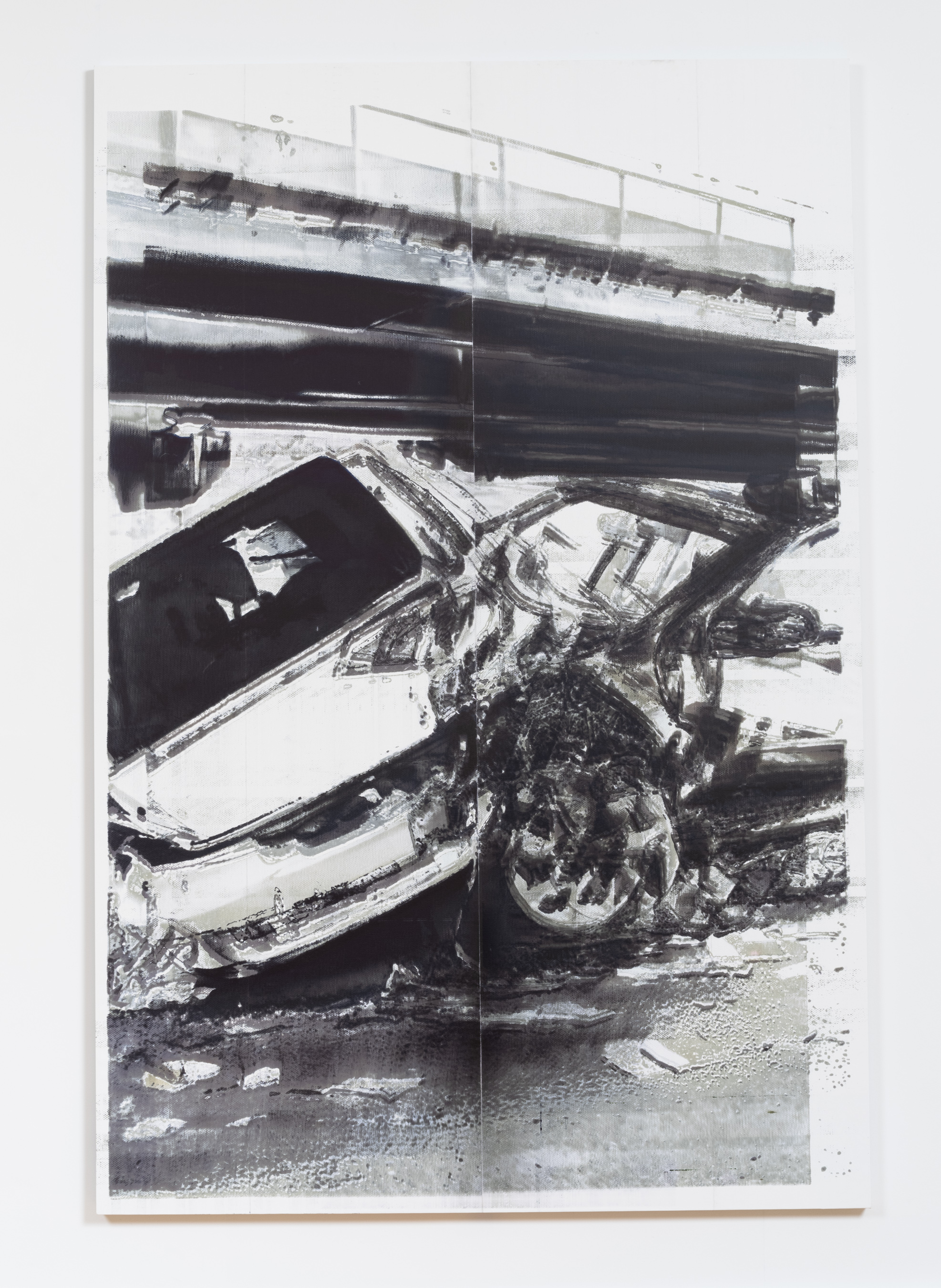

White Car Crash, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Kapp Kapp.

Upon entering the show, the viewer meets Blair’s Crashed Car (Flat) (2024), a cropped snapshot of a wrecked vehicle, doused with splashes of violet and rust on its body. Upon closer examination, the image feels unstable or uncanny, not quite hand painted but also not entirely photographic. This effect of image hybridity epitomizes Blair's inkjet paintings — depicting generated images of car crashes (an overt Warholian homage to the Death & Disaster series), they interrogate how the feeling of a painterly moment can be manufactured in an iterative negotiation between human and machine.

In his towering White Car Crash (2024), layers of ink appear to vibrate and bleed into one another, an indication of Blair’s multistep process of producing images in AI, slicing them into layers, then repeatedly running each layer on canvas through a printer. The result is a reverse engineered painting — Blair’s approximation of a human touch via machine achieves, paradoxically, a potent expressiveness.

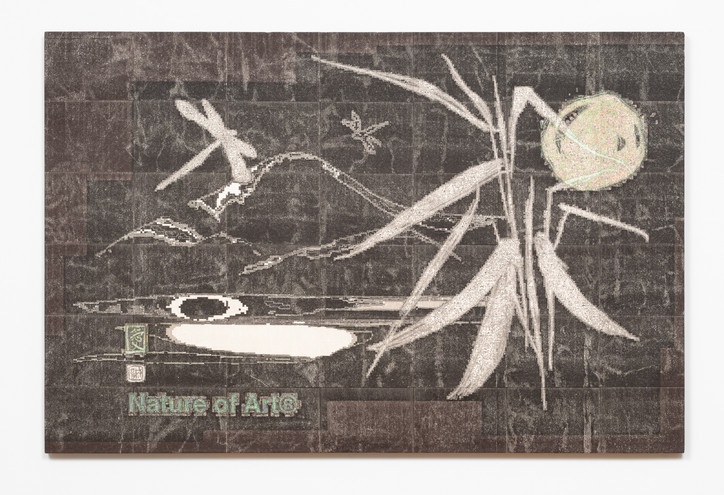

Kunning Huang, Untitled (nature of art), 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Kapp Kapp.

In Huang’s answer to the “problem,” his referential strategy summons the history of Chinese imagery and rice paper, attaining a lyrical balance between past and present. In the anterior of the gallery, his piece titled Untitled (nature of art) (2024) broadcasts the tongue in cheek thematic tagline “Nature of Art,” alongside imagery lifted from an early Qing Dynasty painting manuscript — a graceful pond scene, complete with grass stalks and dragonflies. But the objects and their surroundings seem tonally inverted and actively glitching, indicating Huang’s treatment of rounds of image processing in the preparation stages of his practice. Quilted in tiles, each panel of the work undergoes an intensive process: a specially rigged Canon printer impresses onto an acrylic sheet and thereafter, Huang rubs the printed ink directly onto rice paper, continuing a technique performed in ancient Chinese woodblock printing. The porous nature of the material causes the CMY ink colors to separate, culminating in a pleasurably pixelated texture. In this manner, Huang’s historically enriched approach demystifies present day conceptual concerns and technologies as existing within deeper lineages.

Waseem Nafisi, Bar Peasants (after Malevich), 2023

Second Impressions (after Malevich), 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Kapp Kapp.

Nafisi similarly leads with an art historical reference — the paintings of Kazimir Malevich — in his playful interventions into the thrust of post-modernity. In Bar Peasants (2023), a distorted copy of a brightly colored Malevich painting is bisected by a stretcher bar that literally juts out from either side of the canvas, while also appearing to nudge forward a horizontal sliver of the image — yet this tromp-l'œil unit remains physically flat on the canvas. Nafisi accomplishes this effect by constructing a to-scale miniature “stretcher bar” fixed onto a page from a Malevich monograph, then photocopied and printed onto the canvas. As Malevich serves as a stand-in for the crushing sensation of art history standing on one’s shoulders, Nafisi triumphantly pierces the purified image to assert his place in the “now.”

In Second Impressions (After Malevich) (2024), he employs a similar technique of flattened physicality, in this instance introducing a hand-painted wooden feature in the foreground. True to theme, the only occurrence of paint in this exhibition of paintings is merely an image of paint. This ironic demonstration reveals a self-conscious strategy by Nafisi: the painter’s hand itself becomes an image.

It may come as no surprise that as art school peers, Blair and Huang both trained as photographers, while Nafisi studied more traditional painting — all three departed their mediums and converged in the center at technologically-driven painting practices. The culmination of these young artists’ experiments suggests that painting can trudge through the societal jungle of images and increasingly intelligent technologies of today by borrowing from the toolkit of the past — a promise that digital acceleration can, in fact, enhance the joie de vivre of making and experiencing art.

Canon is on view at Kapp Kapp, 86 Walker St 4th Floor, New York, NY 10013 until May 11, 2024

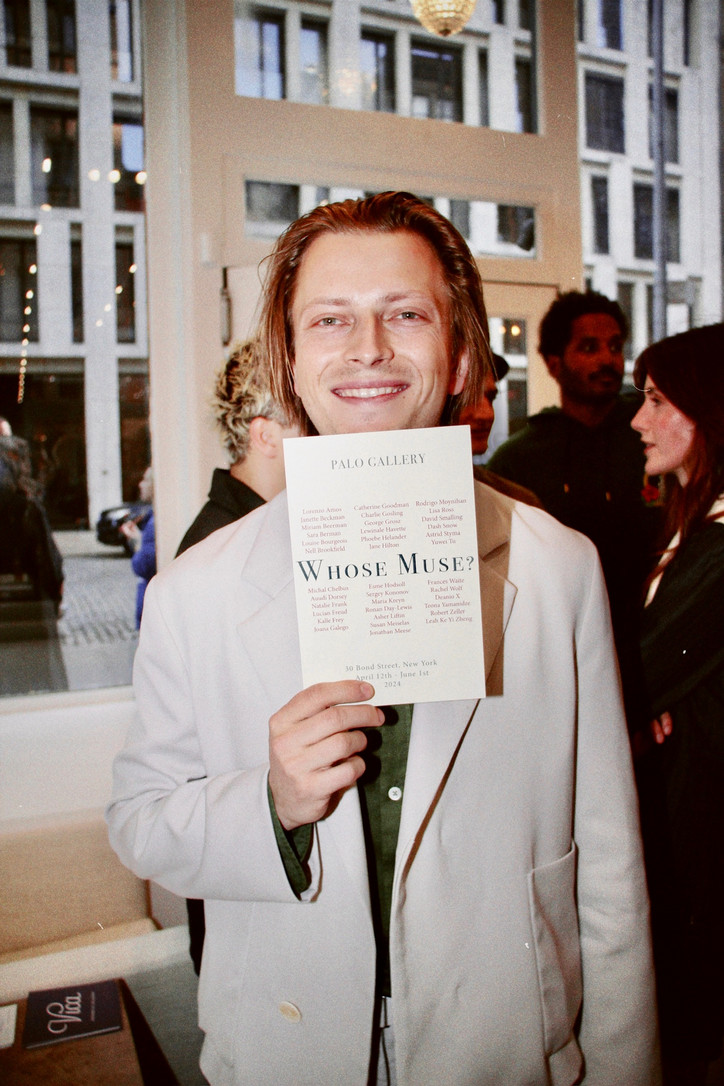

Recently, Paul curated a show, Whose Muse?, at Palo Gallery. Expansively and liberally installed, Whose Muse? demonstrates a boundless curiosity for the contemporary contour of portraiture painting and its limit. Problematizing the assumed parameters of muse as a passive recipient, Paul’s curatorial maneuver focuses on how the status of muse is granted but never a given. In line with his commitment to emerging talents, Paul highlights rising stars in the exhibition, who also happen to have posited some of the most enigmatic and provocative thesis on the absence and presence of muse in the contemporary landscape of portraiture painting.

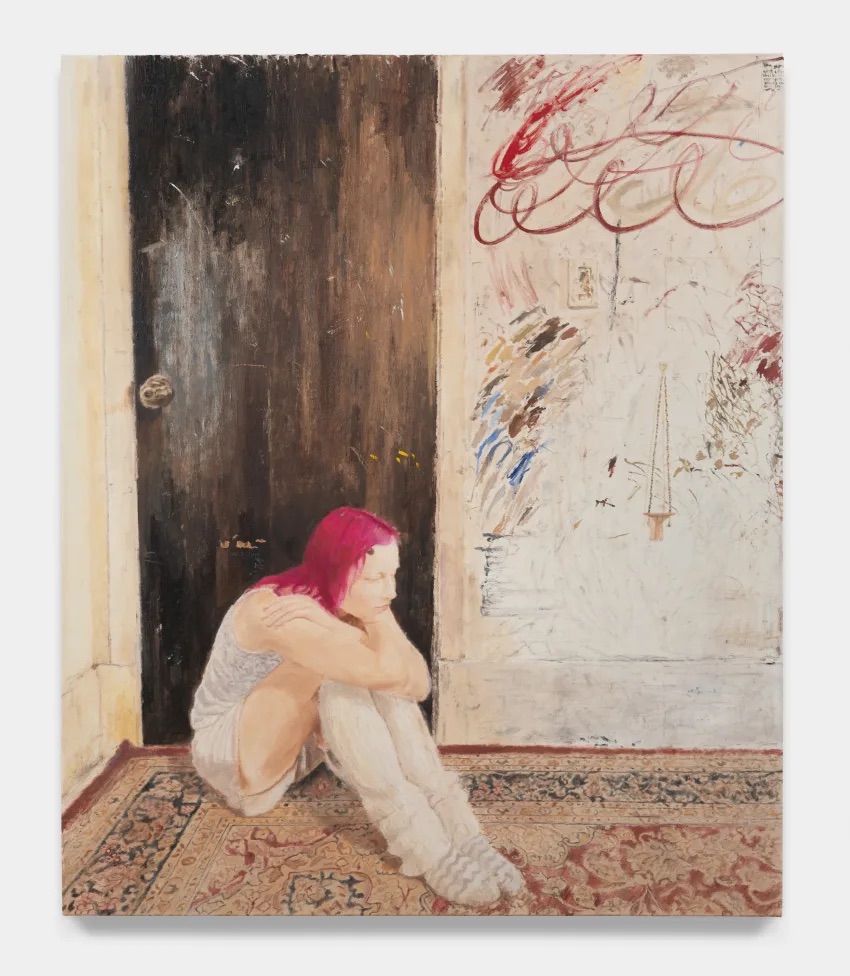

(left) Lorenzo Amos, Girl with pink hair / Analiese, 2024. Courtesy of Palo Gallery.

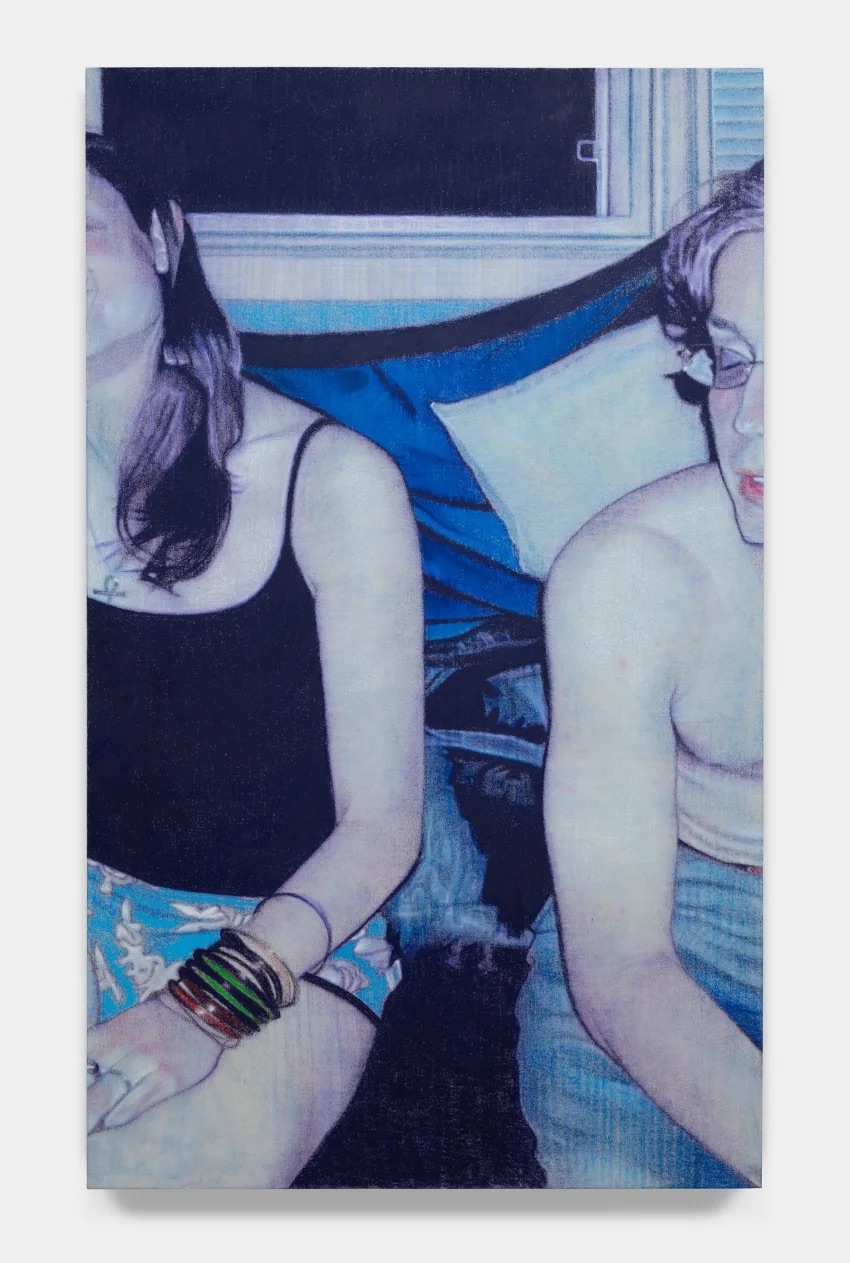

(right) Ronan Day-Lewis, The Space Between Us, 2024. Courtesy of Palo Gallery.

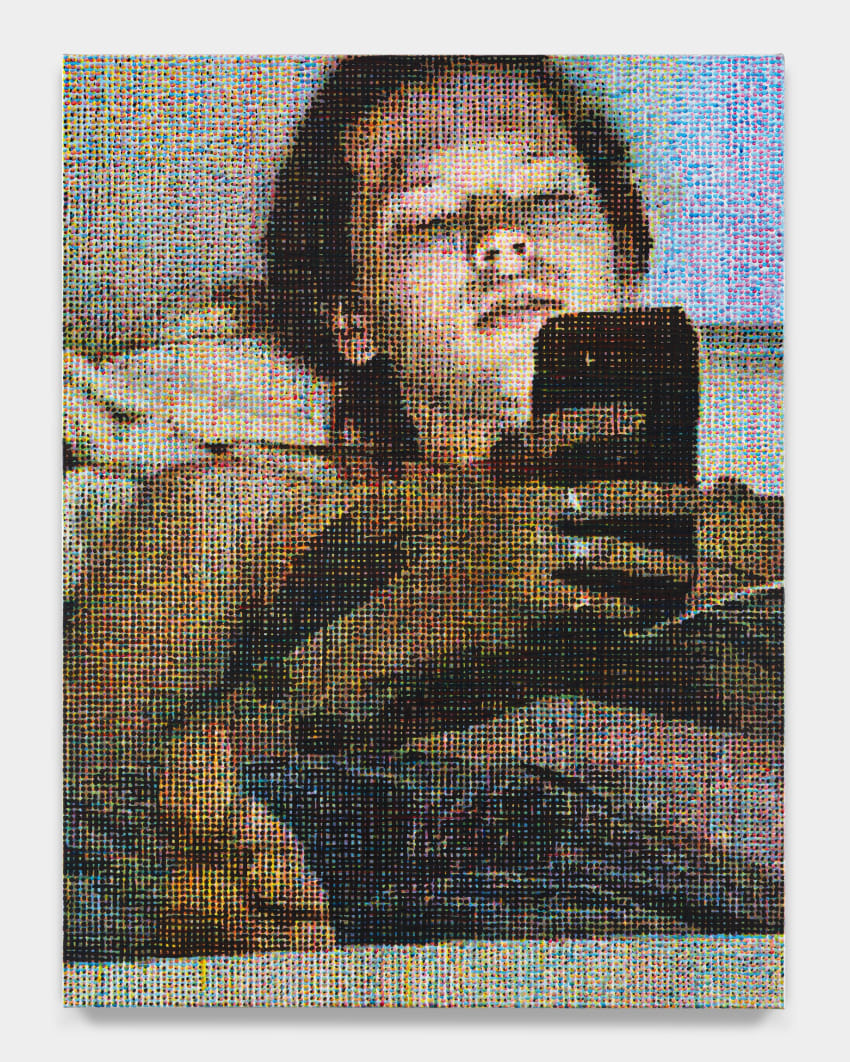

For example, Lorenzo Amos’ Girl with pink hair / Analiese hides his painterly gaze in the abundance of gestures and impressions. Alternatively, Ronan Day-Lewis designates archives of images floating on the Internet as his source of inspiration, in the case of The Space Between Us. Asher Liftin’s Miles Reading takes the digital impulse to explosive ends, bracketing otherwise unseen pixels as units of perception. Elsewhere, Charlie Gosling’s self-study series outright denies viewers access to the artist’s face, the locus of recognition and identification. A similar act can be seen in Leah Ke Yi Zheng’s Untitled (melting woman). The muse (or a fleeting image of the artist) seemingly disappears.

(left) Leah Ke Yi Zheng, Untitled (melting woman), 2023. Courtesy of Palo Gallery.

(right) Asher Liftin, Miles Resting, 2024. Courtesy of Palo Gallery.

This exhibition is called Whose Muse? and most artists in the show seem to be troubling this historically problematic notion of the muse. Shall we start with your curatorial strategy responding to the question of muse?

This whole conversation started because we wanted to do a show on portraiture. I found that there is a small group of very brilliant artists, loosely inspired by British academic painting, who are working in a very real portrait mode of paintings. Quickly, when it comes to showing portraiture, the inevitable question is who is being depicted and what’s the relationship? My curatorial strategy toys with the historical idea of muse, and the difference between the muse and portraiture subject, the latter often appearing in paintings commissioned by powerful figures in an official capacity.

My research discovers that contemporary women artists are not only painting a great deal of self-portraiture that deviates from the historically troubled muse but also intimate familial relations that are more balanced in terms of power dynamics. Ultimately, I am interested in complicating the trope of male artist and their muse. Through proper research, it is much more apparent that Kiki Montparnasse or Elizabeth Siddal, who have unfair reputations for being poor, helpless women, were brilliant artists in their own right. Siddal had just as much influence on the pre-Raphaelites as anyone in their circle. To me, the muse as a participatory subject in the creation of the work becomes a running thread. The question mark in the exhibition title is to look at the breadth and complexity of these relationships, especially in the 21st century, where we have artists who are working without an actual model. Ronan Day-Lewis just grabbed an image of one of these weird images people post on Flickr for his painting. It was a picture from someone’s digital camera from the 2000s. He cropped and painted it into an incredible portrait in the sepia tone. Ronan will never meet them and has no relationship with them, he’s just fascinated by the mystery of their lives.

I am glad you mentioned the role of digital technology. As I understand it, there are quite a few artists in the show who are responding to how technology complicates this more expensive reading of muse-artist relationship. Could you talk more about those artists a bit more?

We live in a world where we are inundated with the idea of a portrait, right? We can take hundreds of portraits a day on our phones, but it is not the same as a true relationship to or study of a human. In most cases, the traditional portraiture is just as much a painting of the artist as that of the sitter. In spite of sounding arrogant, I wanted to put together an exhibition that encourages looking at images and depictions of other people again. Asher Liftin made two portraits for the show. One of them was based on an iPhone picture of his friend Miles, taken when they were visiting the last Venice Biennale. Asher broke the photo up into pixelated four colorway practice, which becomes a fascinating interplay between digital pixels and printed inks.

David Smalling’s painting is not of anyone, it is a surrealist contortion of a figure in marble. He has gone completely meta with it, using Photoshop to make almost a fetishization of the idea of a traditional, erotic muse such as Venus de Milo.

At the same time, I am balancing that with people who completely reject the technological side of things. Phoebe Helander only works with live models. Esme Hodsoll just told us she needs another three months of sitting!

Lorenzo Amos is in the middle. He would say his biggest inspiration are Mapplethorpe, Freud, Menzel, and Goya. Lorenzo sits with his models for hours, gets them to close and sit and frame up. But he takes photos of them with his iPhone, and that is his reference images to turn into these very painterly paintings.

I’m also thinking about artists using projectors to project images on a canvas. When you put them next to Lucien Freud, which is probably the other end of the spectrum, a very slow considered study, tensions rise.

(left) Phoebe Helander, Orange Eyeshadow, 2022. Courtesy of Palo Gallery.

(right) Esme Hodsoll, Boy In Bed, 2016. Courtesy of Palo Gallery.

You mentioned Freud. There’s a whole group of artists in the show hadn’t been thinking about technology, just because they were making works at a different time. I’m interested in the intergenerational lineup that you’re opting for here. Is this a historical survey? Or are you trying to establish interplays and tensions between the historical and contemporaneous.

I would love to do a historical survey of portraiture, but I don’t think we have the access or the wall space to go as far back as I would like to go. However, you can’t look at the state of new academic painters, like Lorenzo Amos or Sergey Kononov without considering Freud because he is certainly one of the most important post-war artists working with the idea of muse. Freud also had quite a reputation for being rather horrible to his subject. Nicola Bowery and Sue Tilley have both written books about their complicated relationships with Freud. But he is the ‘father’ of many of these painters working today and having this exhibition without his work felt some somewhat off.

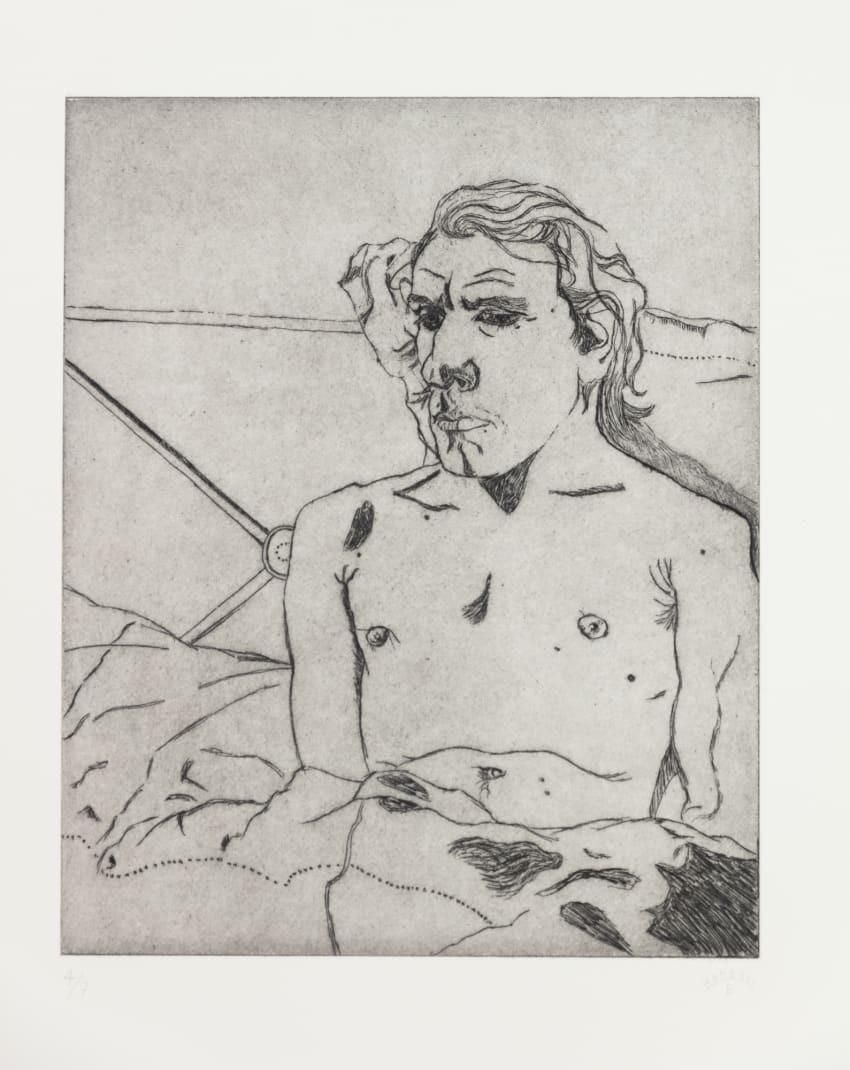

I also selected a George Grosz drawing Artist and Model in the Dunes, which is a very sexualized study he did in the dunes in North Germany. It’s very cheeky, as Grosz was always slightly tongue in cheek, and still felt very relevant to the context of portraiture. Having a few artists who represent more of the history, even if it's the last 100 or so years was very important to look at this larger picture of portraiture.

George Grosz, Artist and Model in the Dunes (1940). Courtesy of Palo Gallery.

I’m also curious as to, now that you have completed curating the show, what are some of the insights you wish for people to take home?

When I go to the Met, or a lot of other museums, I have noticed that aside from the really, famous ones, like Mona Lisa, a lot of people move past portraits. It is less interesting than a grand landscape or history painting to many people. To me, portraitures often the most interesting. Because of this technical technological profusion that replaces portraits with images of people, we have lost touch with looking at considered portraiture. The show is an attempt to encourage considered looking and think through what representing a person really means. As a story or a vessel, a portraiture is always a complex network of contradictions, intricacies and tensions. Most importantly, I want people to physically be at the gallery to look at these portraits that fill our walls. Even right now, as I start looking at works together, and seeing connections that I hadn’t considered before, my perspective is constantly being slightly shifted. As much as we can put things together as a PDF, it is never the same as having them in the same space.

It seems that your curatorial strategy here goes beyond identifying different modalities of contemporary portraiture, be it seated, observed, or self-portraits, and really fleshing out the more intellectual and aesthetic implications of creating portraitures in the age of device saturation.

I started with the idea of putting portraits into three categories because we have these three rooms. I have left that idea behind because I thought it was too reductive. A portrait of a model can be just as much an act of self-portraiture as a physical self-portrait, and a self-portrait can be just as distant as copying a found image into a painting to me. I want to be unconstrained in my curation here and explore these more intricate, sensitive relationships when it comes to technology, subject, and agency. It is more exciting and a lot harder to put together a show that avoids using easy marks, but I think it’s going to turn out to be a very interesting conversation.

Whose Muse? is on view at Palo Gallery, 30 Bond St. New York, NY 10012 until June 1, 2024.