CARDIGAN by LOEWE, WINGS by DAUAN JACARI

Stay informed on our latest news!

Stay informed on our latest news!

CARDIGAN by LOEWE, WINGS by DAUAN JACARI

On the walls of his studio, relics of past works intermingle with ideas-in-progress and reminders for the future. A print of his performance Late October (2020) at Galleria Continua, on the outskirts of Paris, hangs above a leather sofa; to its right are an assortment of pinned-up sketches, notes, and images. A floor to ceiling mirror across the room lists Greenberg’s 2024 exhibitions and performances written in dry erase marker; the stacked calendar includes the Venice Biennale in Italy and the Yokohama Triennale in Japan, as well as a solo show at Buro Stedelijk in the Netherlands.

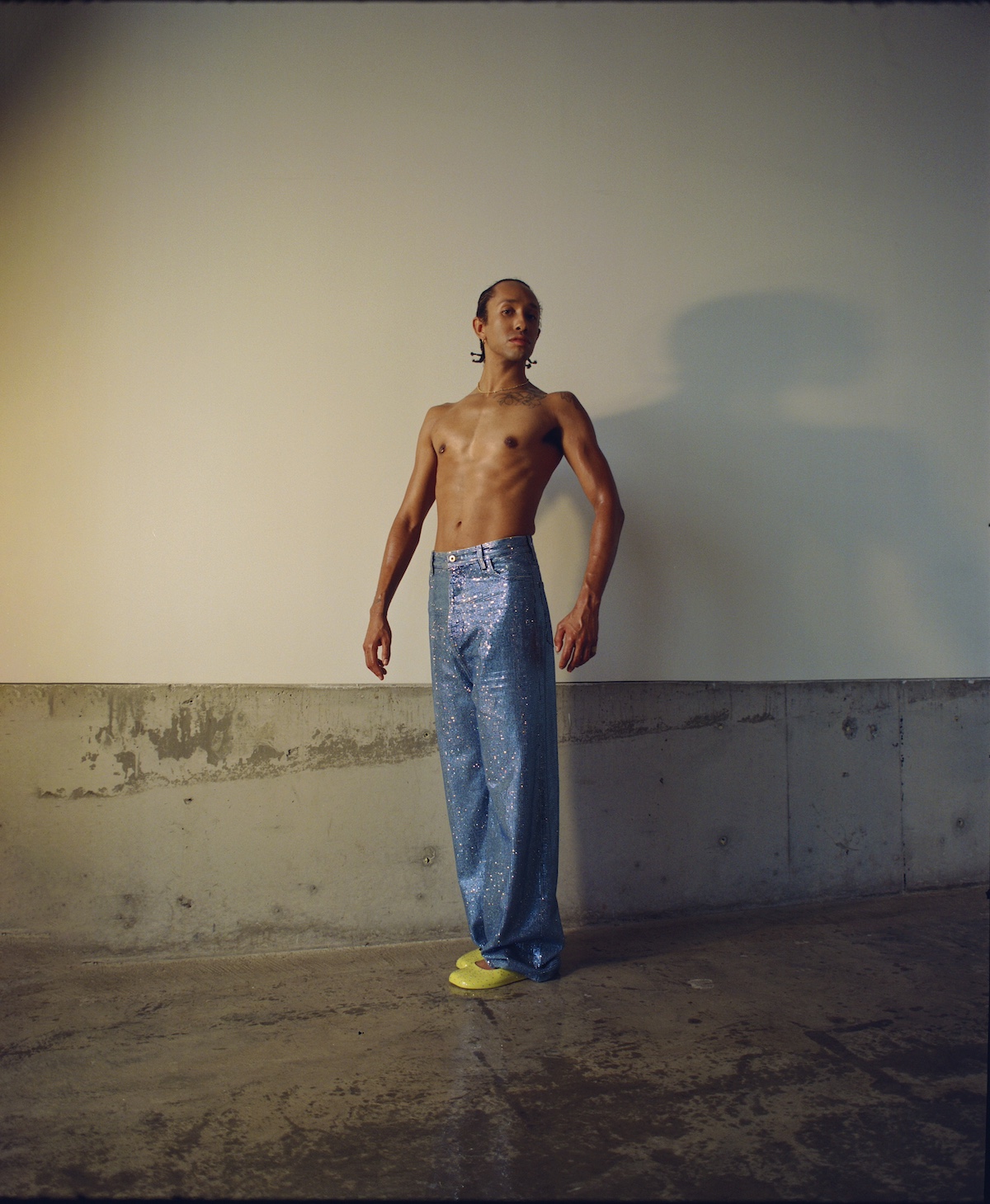

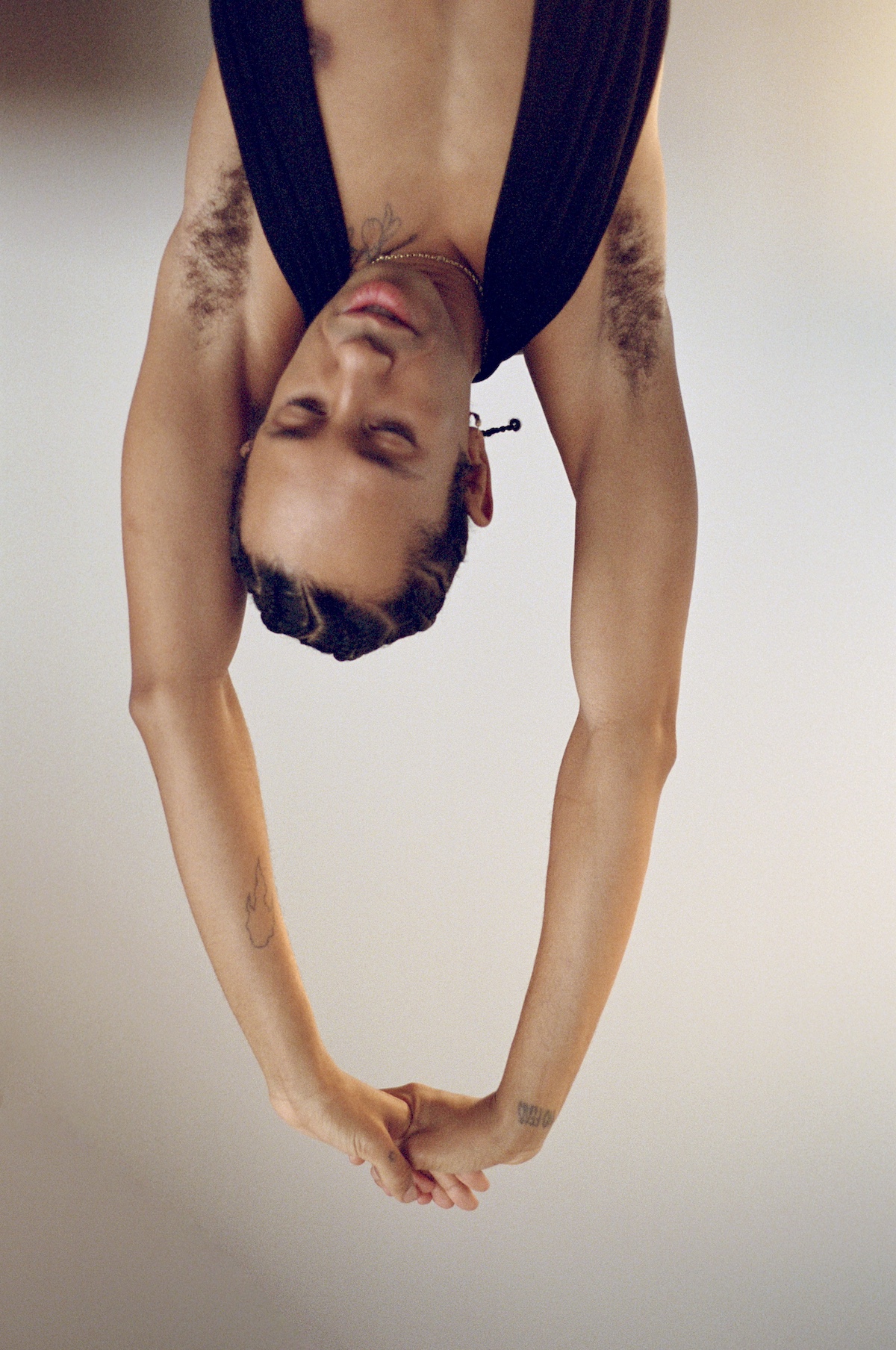

FULL LOOK by LOEWE

Greenberg can approximately be described as a performance artist, though as he explains to me later in our conversation, he finds the term “artist” alone more accurate. His work can also be understood as a form of sculpture, shaping moments and scenes with human bodies in site-specific durational works that often stretch across hours and hours. Born in Montreal and raised by his mother, who was an actress in a Russian absurdist theater troupe in his early life, Greenberg was exposed to a wide range of art and artists from a young age. At 17, he dropped out of school and began experimenting with different forms of performance; by 20, he was invited to study with prolific Serbian performance artist Marina Abramović. Now 26, he has completed residencies and shows at prestigious institutions all over the world, including Palais de Tokyo in Paris, France and the Watermill Center in New York. Last year, he was invited to stage and record his work Étude Pour Sébastien (2023) at the Louvre.

One oft-discussed element of Greenberg’s practice is the rigorous physical training and diet required to condition his body for the strain of durational works, and the particularly strict physical regimen that he undergoes as a ritual in the two weeks before a performance. Given the supernatural themes of office Issue 21, I ask if he has any corresponding spiritual rituals for preparation ahead of performance. A grin spreads across his face. “I do, but I don't want to tell you about it.” I ask him if he believes in ghosts (he does, though he declines to say more) or the afterlife (he passes on that question.)

“What about God?”

In January, Creative Capital announced this year’s grantees, a beautifully colorful and expansive list of artists sending powerful messages through the visual arts and film/moving image. A total of 54 artists will each receive up to $50,000 of unrestricted project funding as well as opportunities to build their network and creative community. So Creative Capital is not only helping to ignite the fire in each artist but assuring that it burns on fiercely even beyond each new work. “We’re committed to not only helping these brilliant artists realize their projects, but to also create the conditions that will enable their artistic practices to thrive,” President and Executive Director Christine Kuan echoed.

This year’s grantee group is made up of 80% artists of color — 20% of which are Native or Indigenous individuals. Northern Cheyenne painter and printmaker Jordan Ann Craig is among that category. Craig uses her work to fuel her imperative pursuit of bringing visibility to the place she comes from.

Jordan Ann Craig always infuses her upbringing into her work, speaking from her personal experiences. Her Creative Capital-supported project will be in collaboration with her mother, Brigit Johnson. Within this work, Books Not Returned to the Library, Craig and Johnson are speaking with authority on an epidemic that has flown largely under the radar for the general public: the rapid disappearance of Native women occurring every single day, at unimaginable rates. This work will include handmade books, each representative of one missing or murdered Native woman, girl, or two spirit — telling their stories on a larger scale, as they deserve to be told.

Below, office spoke to her about her Creative Capital-funded project and what it means to open doors for others, as it has been done for her.

Kayla Curtis-Evans — How do you continually infuse your Northern Cheyenne heritage into your work?

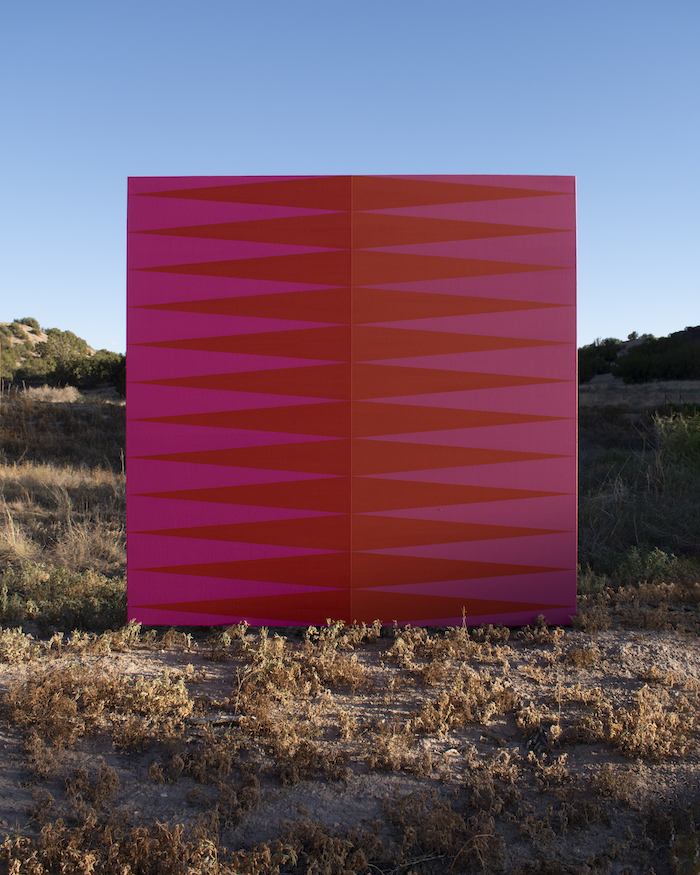

Being a Northern Cheyenne woman, I feel everything I make is inherently Indigenous and Northern Cheyenne. In my practice, I bring in specific design elements inspired by Cheyenne and Northern Cheyenne beadwork and quillwork. I study beaded and/or quilled moccasins, baby carriers, and pouches, adorned in beautiful Plains Indian motifs. I feel very lucky to have incredible art to study and bring into my own art.

How does your current setting of Northern New Mexico influence your artistic outlook?

Color is very important to my work and how I experience my surroundings. In New Mexico, color is highly concentrated and vivid. I often bring that saturation and contrast into my paintings. I am also surrounded by an amazing community of makers and artists in Northern New Mexico which keeps me motivated.

Tell me about your experience so far with Creative Capital and what it means to you to have this organization assist you in spreading this message.

Having Creative Capital support my collaborative project with my mother is huge. Our project is a big undertaking, and we are currently at the beginning phases of our timeline. Having Creative Capital’s support and resources will undoubtedly help us carry out a successful project.

Your installation, Books Not Returned Library, will explore the major epidemic of Native women rapidly disappearing. How does your work act as an amplifier for the many Native stories that go unheard?

Books Not Returned Library is a collection of handmade books in which each book tells the story of a missing or murdered Indigenous woman, girl, or two-spirit. This library is overwhelmingly full, a powerful indicator of a severe and heartbreaking problem in our society. Collectively and individually, the books share the horrific reality of the violence happening against Indigenous women and girls. These books are a physical place for stories to live on. Every person has a story, and many of these stories have been untold or erased. This library is Brigit Johnson’s vision and idea. As her daughter and collaborator, I’m helping her bring this library to life. We are doing this for the countless Native women whose stories have been swept under the rug, including my mom’s sister Amy Johnson, who went missing in 1986.

Tell me about the research that will go into this project, as each “book” in the library will tell the story of a missing or murdered Indigenous woman. How did you discover the stories you wanted to bring to the surface?

Books Not Returned Library is at the beginning stages of research. With the generous funding awarded by Creative Capital, my mother and I are embarking on a research-heavy project that will require community engagement as well as consulting from a range of experts. We will be working with librarians, MMIWG2S experts, bookbinders, craftsmen, and most critically, the many families impacted by MMIWG2S.

You create abstract paintings, prints, and artist books. In this project’s case, you depart from those mediums, the books providing an in-depth visual analysis of just how grave this phenomenon is. Walk me through the process of creating these books and the technical skills applied.

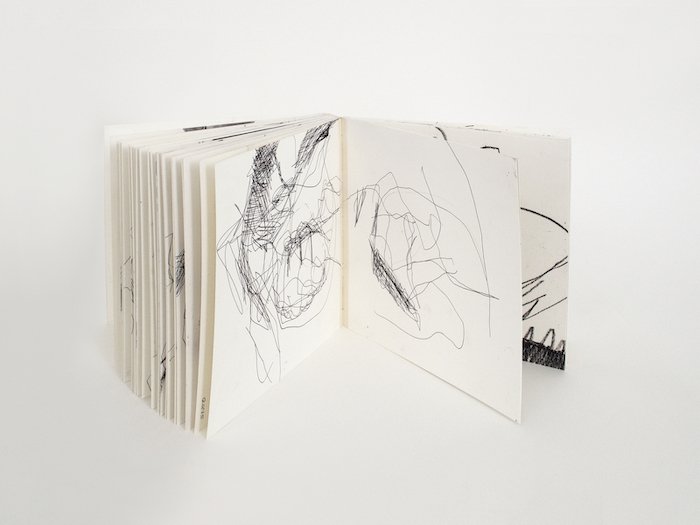

Book Arts is truly a beautiful craft and art. I have been enamored by handmade books ever since I learned binding techniques in college. Each book will be handmade with love and attention to detail. We will be using traditional bookbinding techniques, and add details like letterpressed text to the spines.

Why is it important to you to use your vision to advocate for stories that do not always receive visibility — what do you hope the collective reaction is to telling these stories on a larger platform?

We want viewers to experience the gravity of the MMIW2S epidemic through Books Not Returned Library. We want people to feel overwhelmed, angry, and saddened by the amount of books in the library which translates to missing or murdered life. We want change, we want dialogue, and we want justice. More people need to know of this overlooked huge issue in our society. We are humanizing the available data to ultimately encourage change while also providing a safe space for families affected by MMIW2S to heal and share their loved ones’ stories.

How can we continue to support artists in the ways Creative Capital does?

My mom used to say, “If you just open the door for her, she will thrive.” I have been so lucky in my career that some big doors have opened up for me, giving me the chance to grow, succeed, compete, and thrive. As artists, we get a lot of “no’s” and closed doors. Taking a chance and providing a platform where you can say yes to artists and open those doors can be life-changing.

when i speak to myself i use the kindest language i can summon, i am allowed the same grace i give others

and once i gave myself permission i was radiant