Tommy Cash Dropped a New Single, but Who Really Gives a Shit?

Watch the new music video below.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Watch the new music video below.

I was first introduced to Girl Ultra last year, when a friend sent me EL SUR. I found myself drawn to the album’s skillful eclecticism, evoking everything from LTJ Bukem to Liz Phair to Massive Attack. Despite its many variations, the album is united by Nan’s voice: a strong and synesthetic guide for an eclectic sound, soft but firm and crystal clear.

With her new single freshly out in the world and a hometown concert scheduled for this Saturday at Mexico City’s spacious Auditorio BB, I met with Nan at her home to hear more about how she’s feeling in this present moment — mentally, energetically, musically. Her apartment reflects the lush tones of her music: lots of ambient golden light, with personal treasures arranged throughout. “I just like things that make me feel happy and that remind me of somewhere or someone, so I have plenty of stuff that used to belong to my grandparents. I like to feel cozy.”

And cozy is a great word to describe her music: not in that it’s all overly tranquil, as her songs are often infused with deep feeling, but in that you feel very close to her both physically and emotionally when you listen to it. EL SUR in particular feels directly honest, with songs about sentiments refined to their purest form; “Nada q hacer” muses on ennui and dissatisfaction, while “Amores de droga” laments destructive love.

For Nan, songwriting is a way to connect with universality. “It's very personal and visceral and raw,” she explains. “But then people ask me, ‘Is this song about this person?’ And it’s like — no, it’s more of a collage of [experiences] where the feeling is the same. You find that rawness in different experiences. For example, saying goodbye. It's not just one person that you've ever said goodbye to. You've said goodbye to things in life, to versions of yourself too. So you just try to find that feeling in every verse, in every space in the song.”

As we shot her portrait in the living room of her apartment, I browsed her shelf of extensive CDs. Her favorite albums from the collection? Boards of Canada’s Music Has The Right To Children (“Very ambient, a lot of textures — an album that I can play at any time of the day”), Madonna’s Ray Of Light (we gushed about this to one another, as it’s been the soundtrack to my year), and Julieta Venegas's Bueninvento (“One of my favorite Julieta albums'').

It’s hard not to hear a range of 90s and 00s influences in the Girl Ultra catalog. “I feel the way that I communicate within music — when I make music — is through [what] I listened to, and the references [there] … Most of the music that inspires me comes from an electronic perspective, with a pop sense. I really like Everything But The Girl, Savage Garden, or even The Cardigans — stuff that used to [play] on the radio but [with] a more niche sense.”

Influences are an important part of Nan’s story. As someone who grew up in Mexico City, the energy of the metropolis is nearly inextricable from her upbringing as an artist. Stepping outside for more photos around her neighborhood, I found that the sights and sounds of her neighborhood echoed the layered sounds and punctuated rhythm of the music we were speaking about — a comforting anchor for her to return to after many days away on tour. “I like seeing the same people in the park here, in the morning, and the same lady that sells avocados outside the supermarket. I like to have these little reminders of what Mexico City is.”

Mexico City has historically produced a range of musicians whose influence can be felt around the world, and Girl Ultra seems poised to join their ranks. Well-known among a North American audience (she opened for Alicia Keys’ Mexico tour dates and toured the US to much acclaim earlier this year), what is even more assuring of her stardom is the artist’s combination of stage presence and vocal dexterity. In her NPR Tiny Desk concert, she sings with conviction, hair whipped from side to side as plays alongside her band.

Looking toward the future, Friday’s hometown concert may be just the beginning of the next chapter, but it’s a meaningful one for the musician. A fitting end to a long tour and a tribute to the people and the place where it all started. “It's a very Scorpio season thing. A very friend-based show — I got the opportunity to make it bigger and make the band fuller,” Nan shared. “I always like to finish my tours [here]. I really enjoy being able to invite the people I grew up with [to the concert]. It's such a milestone, returning to your city.”

office– Where’s the name come from?

Suzy Clue– I went through a really heavy 70’s rock phase, inspired by the people around me. It was kind of ironic, because it’s so American sounding, and I just find it funny how American sounding it is, despite how much I don’t actually really connect to American culture like that even though, for the most part, I grew up in America. I’ve always felt like an alien in a lot of ways. American things are funny to me. They feel like movies.

The first version of the name — Suzy and the Clues — has this 70’s sound to it, riffing on Johnny and the Heartbreakers, Siouxie and the Banshees. But I didn’t have consistent Clues. So I was like, “Fuck it. I make all the music. It’s just me.”

How did you start making music?

I was 21 and at first, I was just trying to learn how to play. I was trying out different instruments and one of them was guitar. I was learning covers and then I just started doing it. I used to do this thing when I was younger — my brother was kind of a know-it-all, and so every time I’d ask him if he’d heard of a song, he’d always be like, “Yeah. I already know this song. I heard it a week ago.” So I used to come up with fake songs on the spot and sing them and he’d ask me, “What are you singing?” And I’d be like, “You don’t know this song?” And he’d be like, “No, I heard it a week ago” [laughs] I think it started there.

How has your sound evolved? You said you were in a band and that didn’t really pan out?

Even when I had a band, I just kind of hired guys to play live with, but I always knew what sound I wanted, I just didn’t know how to do it because I sucked at playing [laughs]. So, I’d listen to my favorite songs and from there I learned some techniques as to how I could emulate that sound, bring it closer to the sound profile that’s always been in my head.

You got this shoegaze, goth rock-y thing going on. And — this isn’t to say you aren’t technically skilled — but that sound lends itself to not needing to be the most meticulous guitar player.

I hear you’re flipping between London and New York.

Yeah. I'm actually going back to London on the 29th of this month because I'm playing bass for Viji and she's doing a UK tour. And then I'm coming back; I’ve been back and forth between London and New York for two years now.

Do you think that the music you're writing in London is different than what you're writing in New York?

I think I'm more reclusive in New York, so it does actually affect my music, but London was where I was able to actually feel fully accepted in a lot of ways, so I was able to flesh more of myself out, in the way that felt right for me musically — because I felt so supported by the environment there.

And why do you think that London felt so much more accepting than New York?

It's probably just different for everyone. I got really lucky. I randomly pulled up to London and met the best people. I was like, “This is great. I've never felt this in my life.” You know how you can be in different crowds and think, “Ok, I don’t fit in here.” Then suddenly you meet someone, it just clicks and it feels like you've known them for ages — that's what London felt like for me, but I still love New York. I'm kind of from here, so there's a special place for it in my heart. In New York, I just experienced way more pushback as an artist; I didn’t get as much support or understanding for my music. It's random, I just got lucky in London — for some reason, they just like my music more.

I hope people in New York aren't saying that you suck!

They used to [laughs]

Really? What was that about?

I think a lot of it was that I did suck! [laughs] I was just starting and I didn't know what I was doing. I was writing songs on Ableton and Logic without even knowing how songs worked. I didn't even listen to rock music until I was 21, until the time that I started writing, because I didn’t grow up with any music culture like that. I only grew up with Albanian stuff and the radio — Rihanna, Lil Wayne, Nicki, that's all I knew.

LEFT: SUZY wears TOP and SHOES by BEN DOCTOR, PANTS by GAUNTLETT CHENG

RIGHT: SUZY wears SHOULDER PADS and UNDERWEAR by SH4ME, BRA by ARAKS, SHOES by BEN DOCTOR, EARRINGS by USELESS OBJECTS, and GLOVE by SUPREME

I remember one of the first few songs I wrote, I showed it to my friend, and I was like, “Hey, what do you think?” And she was like, “You need to add a bassline” and I was like, “What's that?” [laughs] I just had no idea. So a lot of it sounded bad. So to all those people who said I sucked — fair enough. But also, maybe people in New York are harsher critics.

I will say, the first musicians I started hanging out with, and the people that I was learning music from — they were all jazz musicians. So, that in itself screwed me over — becasue they are the most critical people, even when they were doing things that were so fucking random [laughs] Not to shit on jazz at all — they just weren’t really fucking with my stuff. If I was lucky enough to meet more singer-songwriters early on, I would have had probably a different experience, probably more encouragement. Not all the jazz people were bad, but it sticks with you.

Of course — especially if you're just starting. Because honestly, when you're first starting, you kind of need those first few months to be like kind of bad and still have people telling you to keep going.

Until now, I’ve never had any type of support for my music. I’m really surprised I didn’t quit, because very rarely did someone have something nice to say about my music.

You also might have just been talking to the wrong people.

Maybe. But I'm also talking about music that I used to have on Soundcloud that even I took down, that nobody knows about.

The Suzy Clue deep cuts. Do they sound anything like “Remember Me?”

No, I was still trying to figure everything out. “Remember Me” is when I figured out how to get that rough sound that I was always trying to get. I used to not know how to do that on guitar before, so would actually sing a melody with my voice, record it, and distort the fuck out of it. So it almost sounded like an electric guitar, and that was how I got that sound– because I didn't know how to do it. That's it. In my old music, it’s this janky version of me trying to make it sound like tough and hard but I just didn't know how. And I’m still learning.

Talk to me about “Remember Me.” Did you write it in New York or London?

I actually wrote that in London. It’s a heartbreak song — just a heartbreak song.

Since writing and releasing, has your perspective on the situation changed? Have your thoughts on love changed since then, or do you still feel that you’re in that mental space?

Absolutely it’s changed. But I think, anytime something happens where vulnerable feelings may arise, I kind of jump back to that. In this song I’m singing, “Don’t you think I’m enough? Didn’t you used to be in love?” And I think, when something like a rejection or a heartbreak happens, you instantly go back to that place of thinking that you’re not good enough. I’m not in that place right now, thank god. Those feelings are temporary, and eventually you can come out of it and realize that sometimes things just don’t work out because they don’t work out. And you can realize that whatever person is making you feel this way, maybe they’re kind of lame and not worth your time. But if I ever experience heartbreak again, I know that I'll probably dive right back into that state, because I think that's just the human experience, you know.

Even just the title of the song, “Remember Me” it’s like you’re talking to the person that you were in love with. But also, the way that the body remembers the feelings you once felt. It's hard to forget heartbreak, no matter how much time and distance you have from it.

Absolutely. The feeling in your body doesn’t really go away, you just evolve through it. And the song in a lot of ways is for women. We have just way more pressure to be good enough — blaming yourself is something that we're trained to do from a young age.

LEFT: SUZY wears SHOULDER PADS and UNDERWEAR by SH4ME, BRA by ARAKS, SHOES by BEN DOCTOR, EARRINGS by USELESS OBJECTS, GLOVE by SUPREME

RIGHT: SUZY wears DRESS by AREA, SHOES by DSQUARED2, BRA by ARAKS, EARRINGS by USELESS OBJECTS

This song as a heartbreak song is super interesting. When people write about longing and heartbreak, it usually has a very distinct sound. Mellow, maybe some guitar — very Phoebe Bridgers, but I really like this, because when you’re heartbroken, it’s not just a peaceful sadness. It’s fucked up. It’s destructive.

Yeah, this definitely represents the rage you feel when someone just randomly gives up on you, or disappears and abandons you and the love you have. There’s an element of asking, “What the fuck? Hello? What just happened? You were in love with me a week ago — why did that change?” And that’s when you start blaming yourself, asking what you did wrong, asking what happened. But at the same time, you want to shake the other person and be like, “I was a person in your life! Do you not remember that?!”

It’s all grief and anger toward yourself and the other person. Because on the one hand, you’re mad at them for throwing it all away, and on the other hand you’re angry at yourself for the possibility that something you did made them want to throw it all away.

Sometimes we blame ourselves for being heartbroken. We’re like, “I don’t wanna feel this right now.” You rationally understand that you have nothing to blame yourself for, but you don’t feel that way.

You’re mad at yourself for being weak. I think in a lot of ways, this song represents both ends of that — feeling weak and feeling strong enough to confront the person. The song feels very confrontational to me. I start singing very softly, asking “Am I still on your mind? Do you still remember me?” I’m asking everything very sweetly, until I become confrontational. I’m like, “You used to be in love!”

Talk to me about the music video — you’re walking through a party, it’s really fun and cute. I wouldn’t have pictured that with a song as thrashy as this one. I like it.

Thank you! I am so glad you noticed that, because that was on purpose. I feel like there's a certain type of music video that happens with this kind of music, and I just wanted to veer away from it and be in my pop girl moment, you know what I mean?

I wanted to represent the themes of the song in a way that’s also relatable — you could be having these thoughts of heartbreak, and then you're at a party, drunk, run into that person and are like “Fuck."

I mean, I know this term has been beat to death by the internet, but the music video and the song is a very accurate representation of feminine rage. It’s like when you’re out with your friends, and under the table, you’re having the worst phone argument with someone over text, but you just have to smile through it and ask for a spicy marg, as if you’re not on the verge of tears.

Yeah, totally. That's why there were those other scenes of me on the beach — those were more intense, more dramatic. The whole thing is very dramatic — I’m on the beach, doing these dances and thrashing around. It represents my inner turmoil that other people can’t necessarily see. I just want to be a hot emo girl! [laughs]

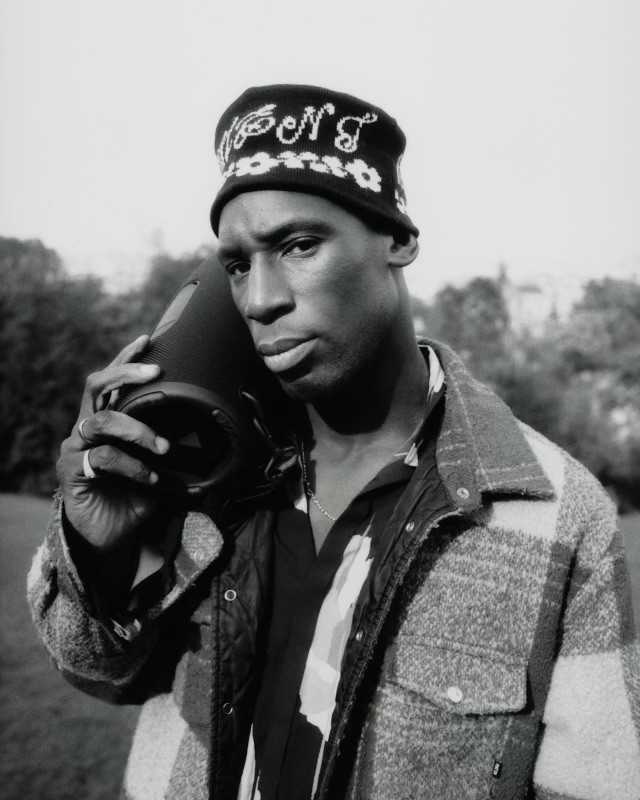

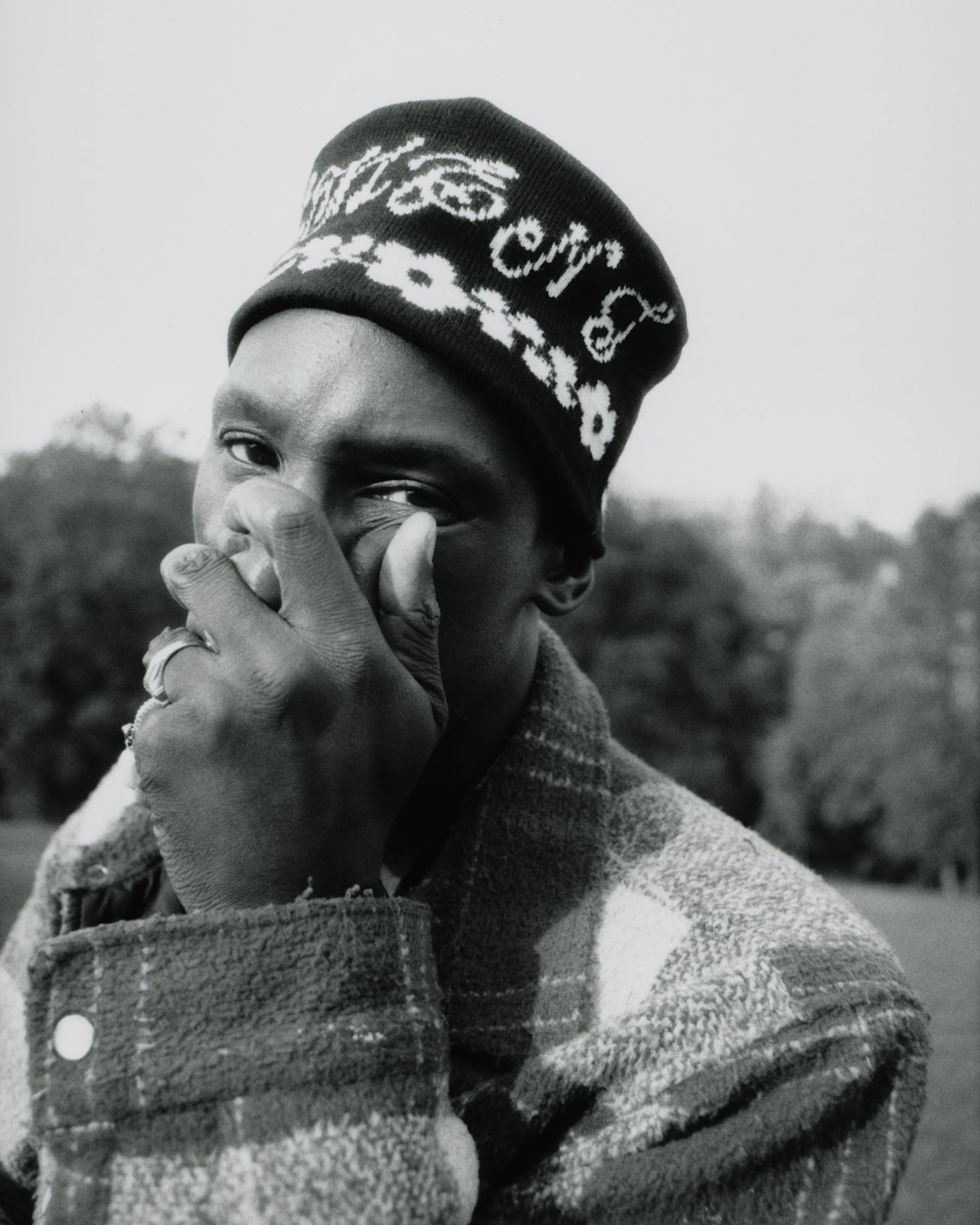

I initially met Oko in 2022 when he played us the album at a small studio in LA. Afterwards, while we ate dinner at Figaro, he danced around the restaurant blasting “Bootylicious” by Destiny’s Child on his beloved boombox (also known as Josephine). He was completely free and unbothered by the world around him, much like when we got on the Zoom call to do this interview. He is all smiles as he answers the phone and starts to give me a tour of the house where he is currently staying in Italy. He proceeds to tell me about his upbringing, the past few years of his life, and his personal vow to give back to those who have so graciously given to him along his journey.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Olivia Roper Caldbeck— It’s good to see you. Where are you right now?

I'm in the Italian Dolomites, doing my residency. It's really nice to have the house all by myself, so I can rest and think about my next project. I'm alone with all my books and my keyboard. I have space here.

Well, thank you for taking the time to do this interview.

Of course. I have my wine and my cigarette. I think I did one interview back in the day, like in 2008 or 2009 when I was doing my exhibition in Portland, Oregon. I needed to talk now because I want to give back to America what they gave me — so many different states and communities. I spent a lot of my escape and street times in America, it was incredible.

What do you mean when you say “street times”?

I was homeless and away from my family for a while. Of course, dance helped me to survive, but it is the way it is. Sometimes I have to be rough, but traveling and art helped me to calm down. Meeting all these people from all these cultures helped me to escape the ghetto during the rough times. I came from a really poor family, and so I had to be awake super early. I had to be so active to escape and also in a way survive. I had to lie, you know, about my situation at home. I had to pretend that everything was OK. I'm talking about me, but I'm talking about so many children of first and second generation immigrants in France. Our parents were making all of these things possible, but we were kids, so we didn't understand that. I can just say that I am lucky to be fine today at my age and to do what I do. That's why I say the street is my education, because I was on the street since I was six years old.

How did you originally get into making art?

I've been doing that since I was a child. My dad was a painter, dancer, boxer. I was really in the mood when I was a child, like dancing every time and being a leader for parties at school. I was always the funny man with the biggest guys.

Do you feel like you had a strong sense of community growing up in Paris?

Yeah, because we were all the same — the rich and the poor and whatever — the people, we were mixed together. It was really nice, sometimes when you came from school or your house you could go to the neighbor’s house. It was not like it is today, it was more chill and I did not face racism until later on.

Was there a point when you knew you wanted to be an artist?

I didn't decide to be an artist. I started to teach dance when I was 12, and I was a teacher for a really long time. When I was 19 I was dancing for big artists and I was sleeping on the street the same night. I just say to myself, “I will never be the slave of someone.” But I never said to myself, “I'm an artist.” I just went through it.

What age did you come to the States?

I first came in 1999 when I was 12, and my dance group brought me to the Twin Towers. Later in 2007, I met some crazy group of architects in Paris, and they brought me to LA. I was a photographer at that time for indie artists and I met some people that brought me to Oregon.

From then I really start to say to myself, OK. I'm a good writer and I love dancing, but it's not enough. I tried to experiment myself and use photography and super eight film to make shit happen. The community of Portland, Oregon helped me so much, they gave me so much free stuff and space to make my shows. A lot of artists helped me and believed in me so much. I jumped into photo, then films. I started to perform spoken word, and from spoken word, I became a ghostwriter for people and I started to make my songs. It was all self taught.

Was it a coincidence that you dropped your first full length album on your 40th birthday?

Yes and no, because I had a lot of issues with that album. First, my producer died. Philippe Zdar was one of the biggest producers in France and he was the guy who helped me to believe in what I do, and to put me as a producer. Then COVID happened and it was a really terrible situation for my family. After some weird shit happened, I decided to open my own company and I was like, “OK, let's do it at 40.” This album is more the end of what I can do right now, it's not just about the music, it's about everything that I do because there is so much archive. I've been quietly working so hard for 15 years. One thing that I’ve learned is to be fucking patient and just wait. So it was real therapy for me to put this album out to the world.

You've traveled so much and had so many lives and been a part of all these different communities. Where do you consider home?

I was born and raised in Paris, and I’m based in Paris. I'm living a seven minute walk from my mother and this is never gonna change. I'm writing so much and I'm doing so many projects that I have to stay in the movement because I have to see what's happening all the time. But the only thing that’s changed now is that I have had a house for a year and a half. I never really had a house for myself. I stayed with people from 6 until 38, sometimes going back to my mother's house. They were really rough times and I was waiting to be settled. Now that I have stability, and I have a house, I can release the album.

How do you maintain strong relationships in all of these different communities?

I'm always on the phone. Like if I'm alone, just before speaking with you, I was talking with some Italian people, and before that I was talking with people who are in Germany. I have a lot of talks with people because it's so important. I really insist on the fact that the best meditation or therapy that I have for myself with my problems is just to talk. To talk by myself alone, or record myself, or listen to stories of other people. I've been working all my life and I never really had stuff except really strong relationships with people all over the world. I'm the son of my dad and my dad was like that too.

Is that how you’re able to film music videos in so many different countries?

I've been working on this for so many years, so don't think that what you see is new. This song “Nalingi Yo” is dedicated to my mother so I have to do in Brazzaville. I wrote the song “Ordinary People” in Palestine and Israel and it’s through the eyes of my dad and who he was. Since I have a half brother and sister in Algeria and Morocco it was sure to shoot the video in Morocco. My dad left his village at nine years old and had to be a man super early, it was even worse for him than me. I think I just finished the work of my dad.

Where do your different stage personas come from?

I'm a theater person so I have a lot of characters. Every time I'm changing but it depends on the song. For this album there are no characters, I am just Oko on this album. But before I like to play, I'm an actor too you know.

So who is Amir in “Ordinary People”?

If I have a son I'm gonna call him Amir. It's a name that means to be prince, to be loyal, to be great. If I'm a prince one day or if my son is coming, his name will be Amir because we are princes.

What about Mikilis in “Nalingi Yo”?

I am Mikilis in Nalingi Yo because I'm Congolese but not from Brazzaville. So everyone, when they see me, they call me, “Yo Mikilis, what's up?” Some nicknames come with a story but they're all Oko.

What was the inspiration for this album?

This album is the experience and nine different emotions of my life. The first song is about my city (“Paris”). The second one is about love, sex and sensuality (“Naked Love”). The third one is about humanity, and people (“Ordinary People”). The fourth one is about God (“Paradise”). The fifth one is about my first love, my mother (“Nalingi Yo”). The sixth one is about loyalty (”Eagle Landing.”) The seventh is about immortality (“Never Die”). And in the eighth one I celebrate the pain with the fourth season of the year (“Celebrate”). The ninth is “Diamond,” the friendship. It’s more than the songs, they’re more like poetry.

That’s really beautiful. Thank you for sharing your process with me and agreeing to do this interview, I know it has been a while.

I'm glad that I'm doing this interview with you, and I'm glad that I’m doing a real interview in America. I can't wait to come and perform, and show people the real Oko. I have so much to say, and I have so much shit to do.

What's next for you and your company?

My company is Mokili – it's the name of my mother. It means “the world” in Lingala. She's also on the cover of my album, in the picture above me. It’s a way to say thanks and to say that everything is gonna work out — whatever projects, music, film or choreography or whatever shit I'm gonna do is gonna be always at the top because it's the name of my mother, and I can’t disappoint my mother. I wanna produce for some other people and support other artists. I have a lot of projects so we'll see with time.

I remember first listening to the album back in 2022 and watching you dance around the restaurant with your boombox. It’s exciting to see it all come to life.

Yeah. I'm excited. Don't forget the name of my boombox is Josephine. She has a song on the next album. She's making more people happy than me, I think.

Listen to Free Emotion here.