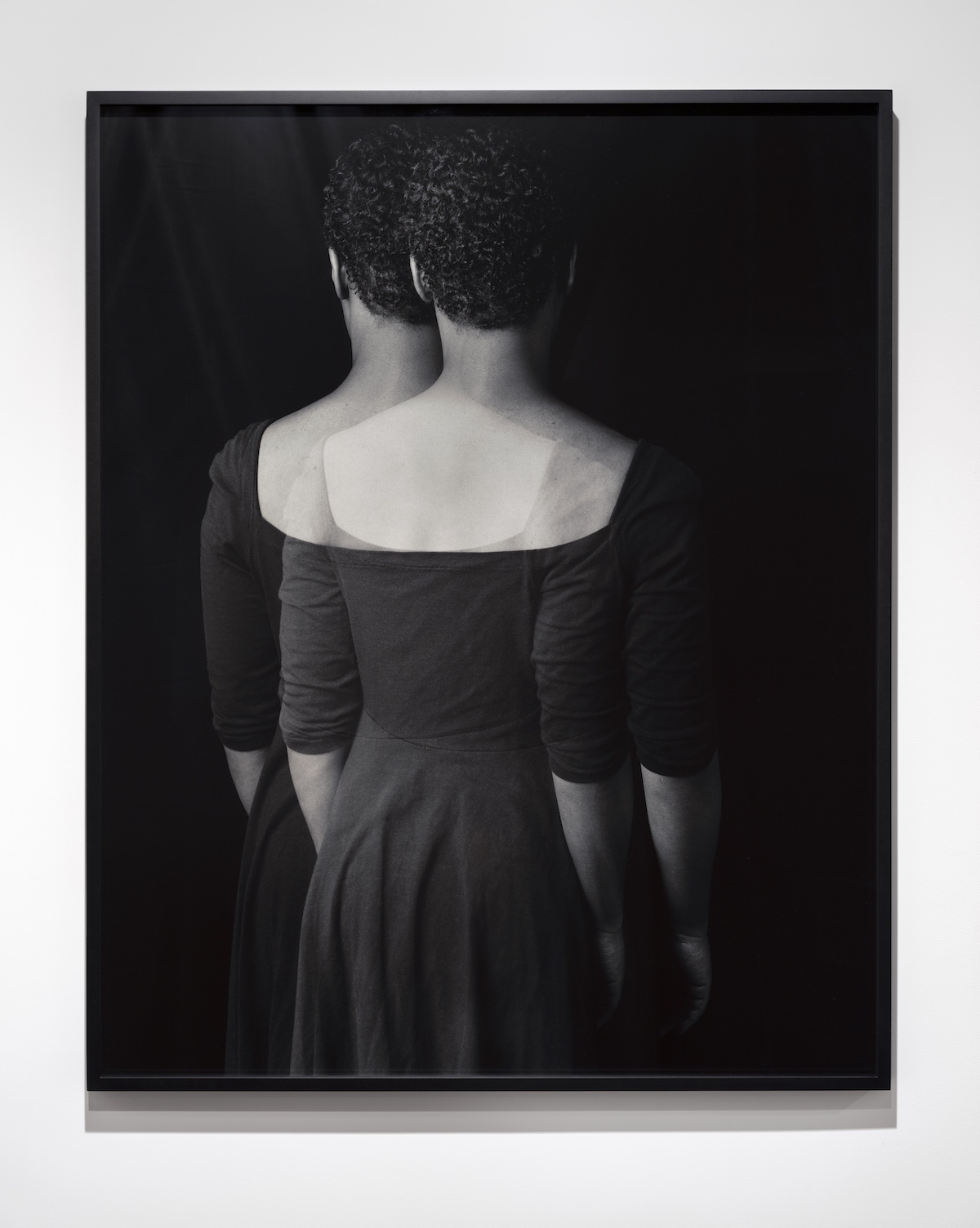

Tiona Nekkia McClodden’s series of paintings Very, Very Slightly (2023) also seduce the viewer into participating in the work, in this instance with prayer benches placed in front of the paintings atop a plush red carpet. The paintings depict advertisements for Black femme mistresses pulled from 1960s and 70s BDSM magazines and are printed on leather, a material that appears often in McClodden’s work. The figures of these women are rendered in black, blue, and red dyes and the diamond dust that gives the paintings their name: a type of diamond known as “very very slightly” or VVS for its subtle flaws that create a distinctive sparkle. The women in the paintings are elusive to the eye and — as I learned when I submitted to the prayer benches — most visible when one kneels before them.

“Especially with the red carpet, I'm definitely thinking about churches, specifically Catholic churches, and spaces of piety and prayer. But there's this other aspect of trying to figure out how to tease at people's desire,” McClodden says. “The best view is on your knees, and that's just it. I had to get on my knees repeatedly to make this work, so I'm transferring something that I enacted for myself.” Very, very slightly diamonds or VVSs are popular references in music, particularly in hip hop — I personally think of the VVS cufflinks promised by Beyoncé to her lover in the “Upgrade U” outro. “I am a child of hip hop, and I was born and raised in the south. I heard it but I had no idea what VVS meant. I was too poor to. And then I got to a certain age and I found out. The idea that the diamond that Black people like the most is beloved because of its sparkle and its imperfection and its shine: I was like, oh God, how beautiful and poetic,” McClodden explains. “And then thinking about leather and the idea of employing it… leather is fine over time, but it still has to shine. “Very, very slightly” is literally how I have to deal with the leather. I can't be abusive to it, otherwise it rejects the work that I'm trying to give it. I thought that it would be something very beautiful to bring my cultural relationship to the diamond and blackness, and think about these Black women as these kinds of diamonds, and figure them as such.”

Very, Very Slightly addresses the connection between the erotic and the unseen more directly than any other work in Going Dark. As both a member of the BDSM community and a contemporary artist with aversions to hypervisibility, McClodden has spent a lot of time thinking about the kinds of pleasures that can only be sustained away from view. “I like to play in the areas of distance,” she says. “I'm not exactly interested in going there all the way — I like not consuming something because it makes me still have a desire for it. In this time where I think there is a desire for the audience to consume everything, to consume ideas, to consume the Black figure in a certain way, I have to have some obscurity to also allow distance and sustain my own desire for my own work.” Her unwillingness to offer herself up to that kind of consumption in tandem with her work is part of why McClodden chooses to live in Philadelphia, where she feels she can maintain a greater anonymity. “Visibility as someone who often tries to hide is really something I'm always dealing with trying to negotiate. Currently I’m at this point in my career where I'm reclaiming a particular space and visibility of how I want to be seen, how I want my work to be seen.”

American Artist echoes a similar apprehension of the visibility that accompanies their practice and career. “The further I get into my work, I want you to just spend more time with the thing I'm trying to say, and I feel like it's going to happen less and less.” When I ask what makes them feel the most exposed, their reply surprises me. “This show. I think the visibility of this show in our professional sense is really next level,” says American Artist. “The idea that anyone could come up and see this thing that is very close to me and has been close to me for a long time does feel sort of exposing.”

To close our conversation in the Guggenheim’s reading room, I ask the two artists which would frighten them more: to be seen always and completely, or never at all?

“To be seen always and completely,” McClodden answers. “I've spent the majority of my life being overlooked, even in the more intimate spaces of family and everything. I was such a quiet kid. I distinctly remember thinking I could be invisible or something. And as much as that could be a painful thing, it actually is immense relief right now, which is what I like. As soon as I get back into Philly, I'm invisible.”

“To be seen never at all is more frightening to me,” American Artist says swiftly and decisively.

As I thank the two artists for our conversation and gather my belongings, I think of the words of Fred Moten: “I believe in the world and want to be in it. I want to be in it all the way to the end of it because I believe in another world and I want to be in that.” As I emerge from the museum, I mentally prepare myself to be in the world again — to believe in it, to relent to its gaze. I prepare to be seen.

"Going Dark: The Contemporary Figure at the Edge of Visibility" is on view at the Guggenheim from October 20, 2023 until April 7, 2024.