Understanding Catalina Ouyang's Poetic Forms

So tell me about this pilgrimage you’re going on.

Ten years ago, I first read Anne Carson's essay “Kinds of Water,” which is her account of walking the Camino de Santiago. I’d say that this piece of writing has most influenced my own, as well as the ways I think about research and citation. So the pilgrimage to Compostela is something that I’ve held in my mind for years as a poetic abstract, and this year took on as a tangible act. My life felt aligned for it. Anne Carson did her pilgrimage with a man she loved who did not love her back, while she was dealing with the slow loss of her father to dementia. I am doing my pilgrimage with my best friend of ten years, while trying to take stock of my triumphs and losses as an artist, lover, friend, offspring, and addict.

A pilgrimage is a spiritual thing, but it is also just a thing to do. The undertaking is formidable but straightforward. I like this as an expression of faith. I grew up in a secular home; my parents did not grow up with organized religion because they were in Communist China. So my limited exposure to religious practice was more social and textural. For instance, in China where I spent summers as a child, as our weekend activity we went up the mountain to the temples where we lit incense and prayed for wealth, abundance, and good health. Beyond that, I was not familiar with any kind of devotional or spiritual practice. Growing up in the US, going to public school in the suburbs, I vaguely understood that some people went to church or synagogue on the weekends. It was not until I was in second grade that I learned that Christmas — which I understood only to signal time off from school and a conifer in the foyer — was a religious holiday that had to do with something called Jesus.

In my young adulthood, studying Western art history, I learned about the Bible and the Church. Those stories about saints and the material manifestations of Catholic belief — the sensual, erotic ritual of them — interested me. I think that arose from both my interest in Anne Carson, who is a very spiritual writer, but also the period of my early twenties where I was working a lot with Chinese mythology and thinking about the impulses behind the creation of these belief systems. They were ways of lending structure to overwhelming longing and fear. While I could not necessarily understand a literal belief in God or the cruelties of organized religion, I could understand intense, transportive desire, and the ecstasies of self-flagellation and martyrdom. So now, perhaps in an attempt to apprehend something I am not yet aware is within me, I choose to walk the Camino.

It’s interesting hearing you speak about Catholicism from this perspective — removed enough to recognize its aesthetic and symbolic meanings and its relation to desire. It reminds me of this one line in Carson’s “The Truth About God”: "My religion makes no sense and does not help me. Therefore, I pursue it. When we see how simple it would have been, we will trash ourselves." Are desire and suffering all that different if one can lead to the other? Is it the pursuit of a thing that gives meaning? There’s the line in the press release about your show: "I have never felt guilt, but I have felt the suffering of others."

Is suffering a central tenet of Trick and what does that mean in your practice more generally?

Maybe not so much suffering in itself, but equivocation and simultaneity. Rapture and pleasure are inextricable from suffering and horror; it's about extremity, it's about intensity.

Trick reminds me of the use of irony in Anne Carson's work in that she's revealing how these different feelings, as you described them, can be superimposed among other structures. Do you think about irony?

In its popular deployment as facetiousness, I detest irony. I find it cowardly and bullyish. However, when it comes to irony in its literary applications, there is a lot to be said for slipperiness and foiled expectation.

My sense of humor is dry, and maybe that is where it coincides with a writer like Anne Carson, who is also ironic and dry. I've been told, and I probably agree, that I speak in a monotone and that my affect is very deadpan. I think the prevailing tone in my work is also one where things are as they occur. I try not to make things too atmospheric in the way that some cinema manipulates emotion or affect with formulaic editing and scoring. I try to keep the work in a space of restraint and strangeness. And I think — without trying to prescribe the term irony in ways that don't fit — in thinking about what I disclose and withhold about the work’s origin and associations, I'm always trying to make decisions that maximize the work's autonomy.

How do you know when you’ve achieved that?

It’s about stopping before foreclosing possibility — when I know that there remain a hundred other things I could still do to a piece. I want to stop before the point where my interventions start preventing the piece from acting in and of itself. As for how I decide where that terminal point is, that comes with practice and intuition. I'm always trying to work just a little beyond my existing skill set. So there is also the condition of where I reach my physical or technical limit, which also determines where I stop.

What does this intuition feel like — especially as it concerns the pieces you finalized while setting up the show?

It's agonizing every time. I think a lot about resourcing and not wanting to waste things before they're ready. So even when I was deciding what objects, artifacts, and hand-sculpted elements I wanted to put in this show or any of the group shows leading up to it, I was balancing my resources and trying to be strategic because I don't want to use a carved wooden limb or an expensive display case for a piece too early and then realize, Oh, I wanted to save it for this other situation. I think that is part of the reason that I work very slowly.

I grew up in the home of an immigrant hoarder. We saved everything, and we did not organize the things we saved. Our house was enveloped in urgency and paranoia. It takes wealth to be able to throw things away; you have to know that you can replace them. So I moved through the world carried by this undercurrent of scarcity. But I think that also allows me to recognize the agency and majesty of everything that I make or collect, because once I bring it into my fold, then I am responsible for handling it with great purpose.

In the studio, I do a lot of Tetris. With the piece Heads, that has the scythes inside the display case — I think I tried out at least ten different objects or situations in the display case before I knew it would be the scythes. And each of these ten possibilities lived inside the case for weeks. It was probably only two months before the show opened that I manically ordered all these scythes on eBay. I don't even remember why, maybe I read something about them, saw them in a film, encountered them in a dream. Suddenly I had all these scythes, and I thought I was going to use them in a different sculpture, but then I ended up storing them in the display case because there wasn't any other room in my studio at the time. And I realized that that was where they had to live. And the papier mache figure that’s mounted sideways on the wooden pedestal in that piece, I originally made that figure to sit on top of the expanded steel structure in Trick, the video piece. But once I had the steel object in the studio and saw the figure on top of it, I realized that my original idea doesn't work, it doesn't serve both objects. They're being wasted in this configuration. So you keep trying other permutations.

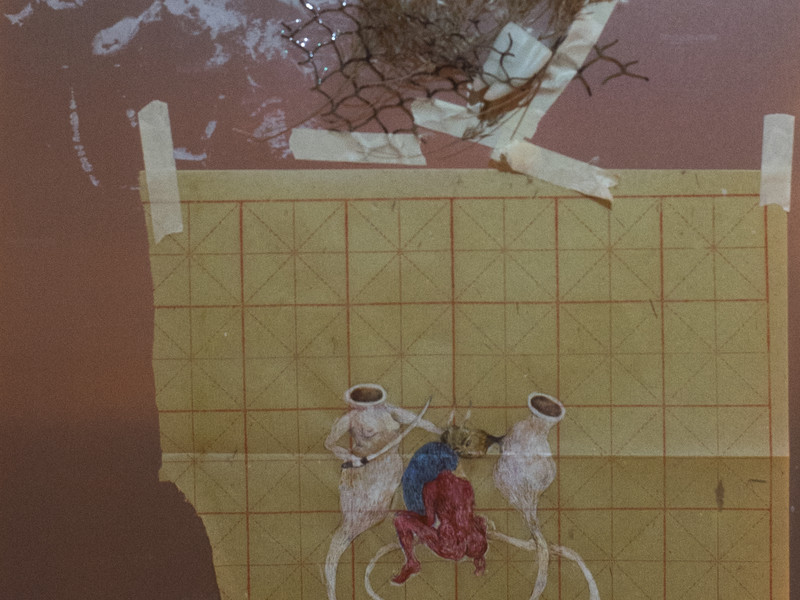

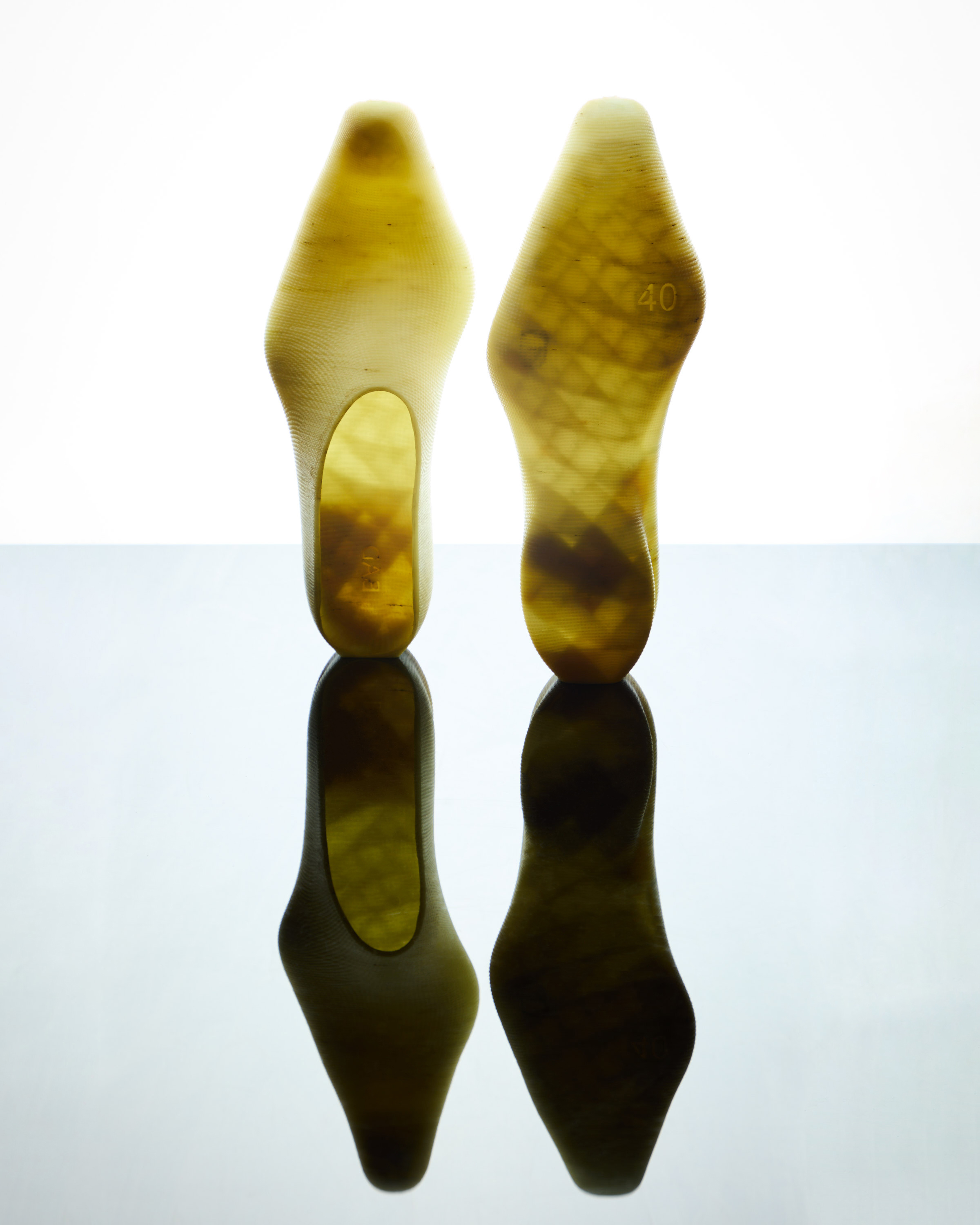

Catalina Ouyang Untitled, 2024

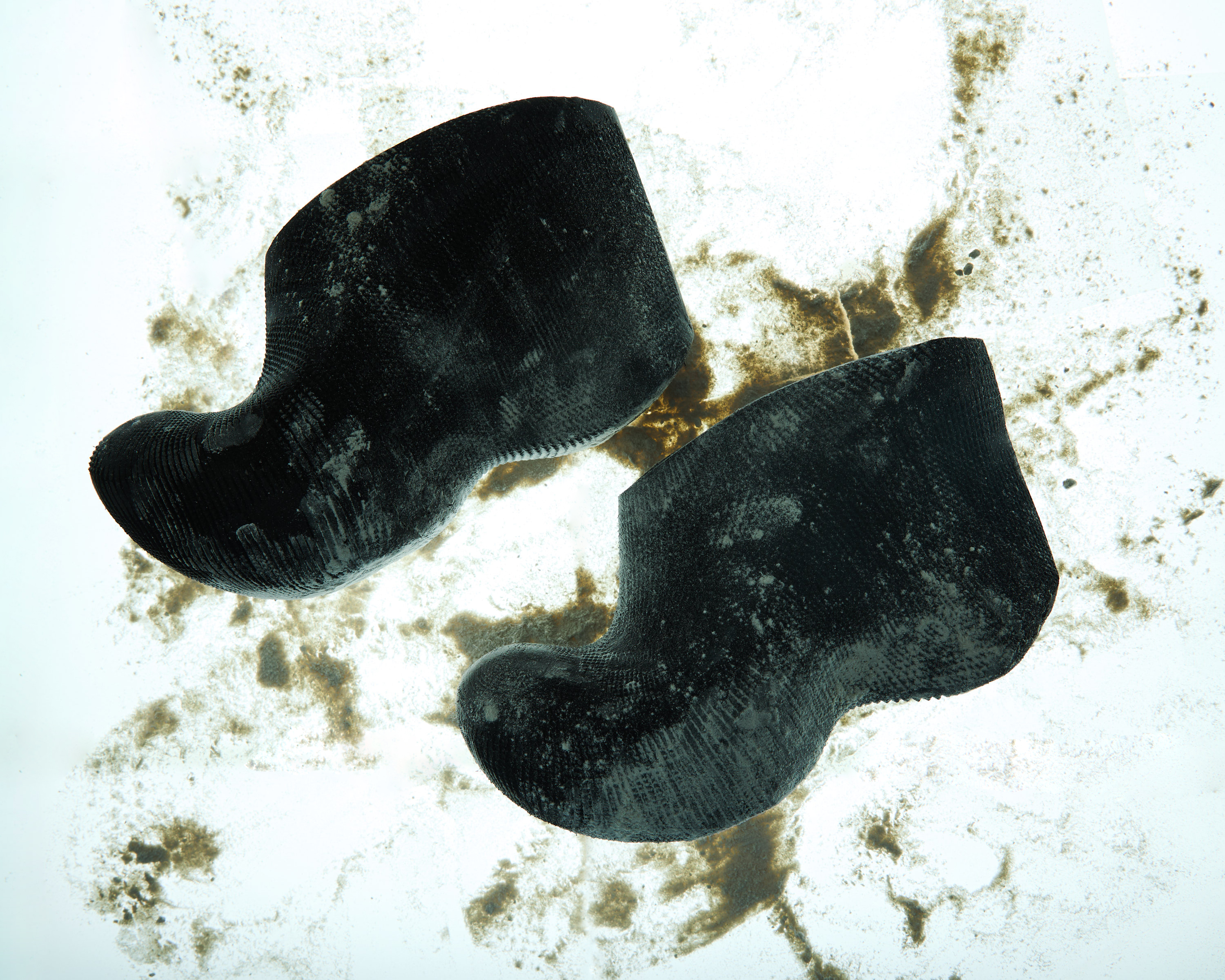

A favorite of mine is this amorphous, dog-like piece bound to the high heel. Can you tell me about the thought process behind that one?

That piece originally began as two separate works. The dog with the long leg on the cart was originally part of a much larger piece that was built around a found auto part that I draped in a resin-soaked piece of fabric. It was a seven-foot-tall sculpture, over eight feet long, and once we delivered it to the gallery, I realized there was not enough space for it. I cut the large sculpture from the show, but I knew that the dog with the long leg and the high heel had to stay. So I thought, Let me amputate that element from the existing work.

The painting verso featured in the final work was originally a standalone piece with a legible image painted on a piece of shellacked gauze stretched over the wooden support from a pet staircase. The original reference image for the painting is of me and a friend frolicking naked in a waterfall, like nymphs. One day in the studio, I had that painting propped backward against the wall, and I thought, That is a much more interesting image. So let me present it that way. Then, suddenly during install I had this dog element excerpted from the larger piece, and I realized that, subconsciously or coincidentally, I had stained the wood of the dog almost the same color as the pet staircase in the painting version. So they ended up in the work together. When I’m in the chaos of the studio, even when I don’t realize it at the moment, all of these things are visually and haptically feeding into each other.

So, almost like putting together the pieces of a puzzle, with pieces that can fit in multiple places.

Yes, and while I can be decisive and spontaneous with these last-minute decisions, they are still intentional. I think about the ways that writers or poets reorder their lines on flashcards, it’s like that. I made everything with sincerity and urgency, so I have the freedom to rearrange those things and have the result be, if not didactic or legible, intentional.

Writers like Carson and Clarissa Pinkola Estés who we spoke about a bit during the walkthrough bring to the present very primordial ideas having to do with the divine feminine, and making sense of these ideas in a modern context. Would you say you’re attempting something similar with your work?

I like rule-breaking not for the sake of rule-breaking, but rule-breaking that emerges from a true kind of self-knowledge. I think that has to do with spiritual immanence in which you feel connected to some kind of truth. Or where you feel truly connected to the unknown. Women Who Run With the Wolves is interesting because on the one hand, the book saved my life at a time when I was young, angry, and almost indescribably hurt. I was on fire. The book’s almost utopian framing of empowerment and, as you said, the divine feminine, did have a meaningful impact for me then. But on the other hand, the text upholds gender essentialist and overly affirmational tropes about femininity in ways that I find less compelling. I am more drawn to the long tradition of melancholic, almost sickly white woman writers like Marguerite Duras and Jean Rhys and, perhaps more contemporaneously, Ariana Reines and Anne Boyer, who write with a kind of spikiness and unbridled anger that really courts conflict — not purely as an impotent mirror to the sufferings of the world, but as a mad grasp for transformation that finds gratification but does not pretend to find resolution.

Yeah, you see that very clearly in Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea. This unbridled anger that bleeds into her story from the other book somehow reminds me of what you tried to do with Brank, the reimagined scold’s bridle, a tool of suppression transformed to one of voice, and housing a poetry reading series on the opening night.

With influence, we take from ancestors that we either choose or are delivered to us, and these ancestors cannot be sanitized. They’re sexist, they're racist, they're rapists, they're abusive, etcetera. Monumental sculpture in itself carries a macho connotation of taking up space, deploying certain kinds of weight and rigidity. Brank is laden with these signifiers at the same time as the piece itself is a transgressive space of active congregation. There was a time when I felt opposed in my practice to reifying the very things that I was critiquing, and that was when I veered most toward the toothlessly affirmational. But I think now I'm much more interested in letting evil exist with its own volition, and refraining from placing my judgment or projection upon the form or feeling of evil, badness, or pain.

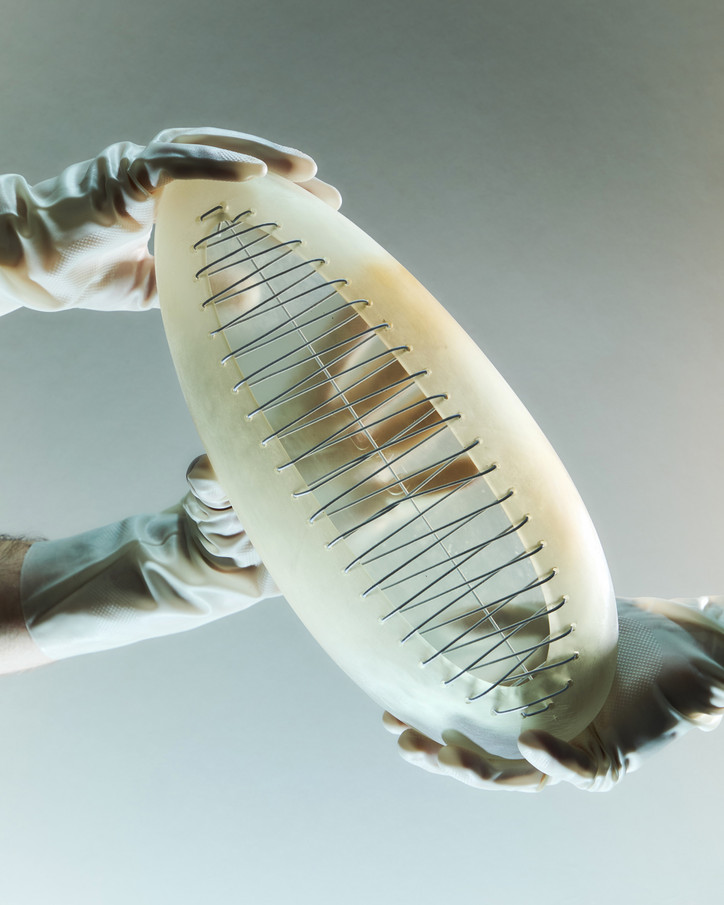

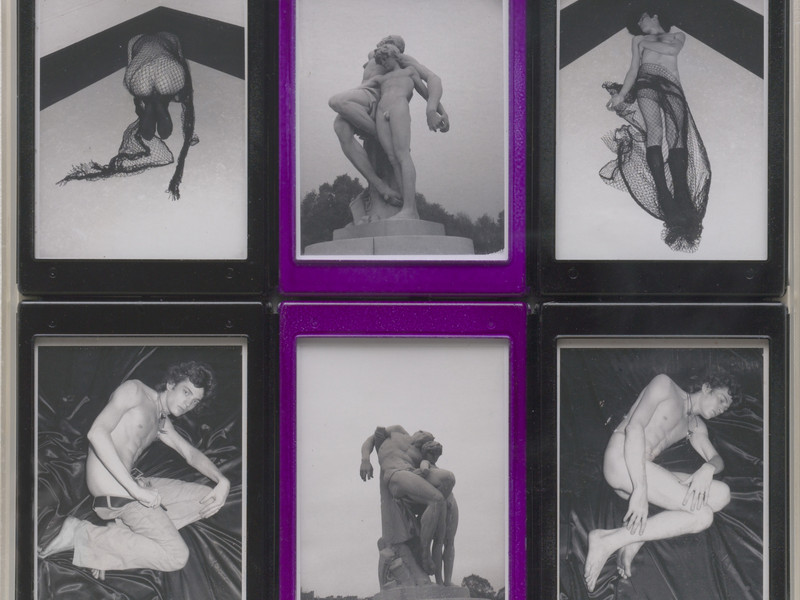

Catalina Ouyang Brank, 2024

True recuperation is also impossible. It was maybe 10 years ago that we suffered through that trend of revisionist Hollywood films like Maleficent with Angelina Jolie, Snow White and the Huntsman with Kristen Stewart, and other stories that tried to instate humanizing origin stories for classic villains and peripheral characters. That was something that I was once interested in in my work as well — the humanity and motivation of historically vilified women or Othered and queer characters. But in hindsight, I find that even in those revisionist narratives, the villain is sanitized into a misunderstood being of kind, good, or justified intention, and I'm more interested in, as we've been talking about, the miasma that exceeds morality or redemption. More like Angela Carter.

Even the desires that are foundational to our living drive — of accumulation, maintenance, and community building — are necessarily concurrent with the impulses of the death drive, which include pleasure, compulsion, individuality, and libidinal fixation. You have to find a way for them to coexist, which I think is what I am always trying to be attentive to in the signposts that I create with decontextualized references to historical figures, poems, and myths. My intention specifically is not to explain the gaps between them and rather to let them be generative in their unruly junctures.

How do the living and death drives show up in your work?

I think contradiction remains the word. With my invocation of the famous artist and courtesan Sarah Bernhardt, I am trying to address the act of selling sex as both an empowering, liberating mode of making a living, and also a survival industry that has trapped, extracted from, and killed many providers. Sarah Bernhardt is an iconic example of someone for whom it allegedly worked out. But there's also a lot of antagonism in my relationship to that kind of work and value-making. Part of my impulse to show paintings in this exhibition reflects how I feel similarly in some ways about painting as I do about my sexuality; it is this asset I possess that can be deployed toward some kind of value exchange that is efficient, but is in conflict with the fact that I want to make objects, I want to make conceptual work. I want to share my life with a lover and be loved without the raw threat of my sexuality and line of work getting in the way.

There are things that painting takes for granted — the picture plane, materiality, a painting’s objecthood or lack thereof — that I take issue with. There are things that my commodification as a sexual being takes for granted, that I most certainly take issue with. There are concessions at play, but still I am intent on engaging with the practices of making paintings and selling sex in honest, risk-taking, and challenging ways. So it's about going into the thing that already feels doomed, but finding some kind of return in it.

Do you think about "goodness"?

No. Sometimes I hear from other people that they're concerned about being a good person, and I roll my eyes. I don't know what that means, “good person,” because you either do things that are not harmful to other people and you act with compassion and accountability, or you don't.

Protestant ideals often equate "goodness" with diligence and labor. In contrast, your work seems to challenge these structures by granting autonomy to your creations. How does this perspective shape the narratives you build?

It has always interested me because of how Protestant ideals often equate "goodness" with diligence and labor. In contrast, your work seems to challenge this by granting autonomy to your creations.

For my whole life, I have been characterized by others as cynical and pessimistic. Which is silly, because I would not have continued making art all these years if I were a pessimist. With every project that leaves me in debt, that doesn't get the recognition I hoped for or even expected, or simply is an artistic failure — I have to be basically stupid with optimism that the next time will work out better, that I will get closer to the truth. And every time, I am optimistic.

The painting Deed is based on stills from the Catherine Breillat film Anatomy of Hell. On the surface, this is a morally confused, nihilistic film. You have Rocco Siffredi, the Italian Stallion, playing a gay man who gets entangled with a suicidal straight woman. And the film seems to be proposing, however problematically, that his having this heterosexual psychodynamic encounter brings him to some kind of salvation. In the end, he pushes her off a cliff and it ends in this violent rupture — is it refusal, pure negation?

Nobody is saved, but something unpinnable is exchanged and transformed between these two characters. In order to create anything, you need to believe that you can move mountains with all the wrong tools and the most ambiguous intentions. Diving into the mess and expecting to reemerge with a revelation — it is hubristic, and it is also a beautiful act of faith.