The Vanity of Medusa

office met with the artists at the gallery to talk about the OG hysterical woman archetype and the curious case of the banana in Ms. Pac-Man. Read our interview, below.

Tell me about the show. How did you come up with the idea?

Smith: We’re friends actually, and we’ve been involved in each other’s art lives, sharing our work with each other. At one point we were kind of joking around at dinner, saying, 'When are we going to do our show together?'

Belanger: I visited Emily’s studio and pointed out a painting and said, 'This is for our two-person show, right?' just joking around.

Smith: Then it became, 'Yeah, we really should do that. Why don’t we do?'

Where did the concept come from, though?

Smith: I guess the vanity table is really one of the first pieces we thought about.

Belanger: Valentine from Perrotin, who gave us the go-ahead to do the show, brought us a model of the gallery space, so that we could start to think about what we wanted to do, and we decided we really wanted to make some work that directly interacted with each other's.

Smith: And this is the one where they most directly interact. We conceived of it together. I notice a lot of Genesis’ sculptures are aggregates—multiple pieces together on a pedestal or on a table or something. I think she even said, 'I’d love to make a vanity,' and I said, 'I’d love to make the vanity mirror, but as a painting.' Then, as she was constructing her sculptures, I realized I wanted to directly reference them as being quote unquote ‘reflected’ in the mirror, which is, of course, just a painting—but the perfume bottle is reflected, various objects are reflected. There’s a kind of absurdity—in the painting is a normal champagne bottle, but in the sculpture, it’s quite surreal and strange. So, it’s like a reverse Through the Looking Glass situation.

Who is the woman?

Smith: This is Medusa—the OG hysterical female archetype.

Belanger: We were looking at images of vanities, and the vanity is actually a vintage piece of furniture—rarely these days do you see a vanity set up in someone’s house. So, we were finding images from old films where the character was this hysterical woman, with crazy lipstick, too many martinis—just a total disaster. The washed up disaster female of the modern era.

Her hairstyle reminds me of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? But she’s not necessarily hysterical.

Belanger: She is hysterical! The fighting that they do—it’s just so unreasonable.

Smith: Medusa has been a bit of a recurring character in my work. The figure is an animated broom handle that transforms into all these different female archetypes in many different pieces I’ve made—it’s a kind of series.

It felt vaguely familiar. Is it the broom from Fantasia?

Smith: Yeah, that’s the broom, that’s the origin. These are all oil paintings, and Genesis’ work is all clay and stoneware.

Belanger: Right, and they’re not painted, so any color is integral. But the pedestals are all covered in 100% wool. They’re wearing coats.

I actually have a desk at home that I made into a kind of vanity because it’s too low to actually sit at. But I love the concept of vanities, especially the word. Do you have one in your house?

Belanger: I live in a 420 square foot apartment, so I have no extra furniture. I barely have a couch.

Smith: But so, yeah, this was the first piece we worked on. There was also this one painting I began thinking about based on one at the The Met by Marie-Denise Viller, that's a portrait of another woman drawing. There’s this kind of beautiful thing of one woman artist looking at another woman artist drawing—there’s this incredible acknowledgement of being a female artist. It was made in 1801, and it's called ‘Portrait of Charlotte Du Val D'Ognes.' It has this really wild backstory, which is that it has been misattributed to Jacques-Louis David, who’s like the ultimate French painter, and it was finally uncovered in the 1960s that it was a female who painted this, but nobody knows who she was or her story. It turned out, she was actually this reputed salon painter.

It’s a beautiful painting that has this light coming from the window, which is one of my favorite kinds of lighting to paint because it positions the viewer on the other side. There’s something about positioning the viewer as if they were behind something, like trying to paint from a new perspective. Anyway, I took my broom lady and put her in the place of the figure in the painting, and wrapped her in the domesticity—she’s wrapped in the curtain which becomes her dress, and she’s looking out the window instead of at the viewer. Then the chaise lounge—I knew that Genesis was going to build a chaise, so I wanted to make sure that’s what she was sitting on.

I’ve always wanted one of those—like a fainting couch.

Belanger: It’s perfect with the cigarette legs.

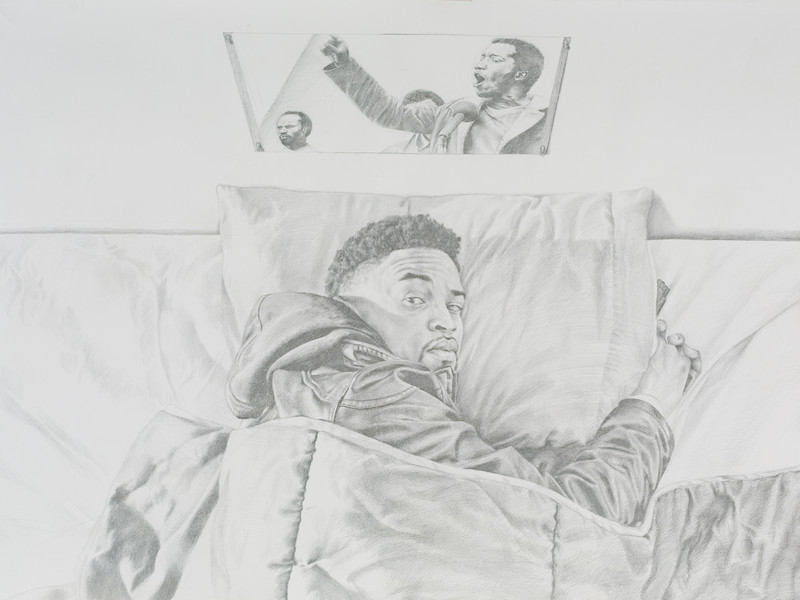

Above: Installation views of 'A Strange Relative.'

I noticed! So, you made it?

Belanger: Yeah. So, Emily had made some paintings that were also referencing more historical paintings and painted in a more classical style—sometimes her work is more pop, but not always. I was thinking it would be amazing if we had one of these more classical, art historical paintings as if it were in a grand living room, and what piece of furniture would be more perfect than a chaise lounge?

There’s something about a chaise lounge.

Belanger: It’s similar to a vanity in that it’s a piece of furniture that’s gendered. You never see a masculine study with a chaise lounge—I mean, that might not be entirely true because there’s those Bauhaus ones, but then it’s called a day bed.

Smith: And then there’s the association of the couch with psychoanalysis.

Belanger: Lots of times, I want my objects to be an embodiment of our psychology. So, how does that manifest in a piece of furniture? I feel like this chaise lounge is a grand lady. And then the bouquet—I think about flowers all the time and how they are a gesture of so many different things: condolences, apology, celebration. But they’re this gesture that’s pretty weak—like, if someone dies, do flowers really do enough? I don’t think so. They’re a band-aid. This is called ‘Double Standard,’ and I was thinking about how men cheat on their wives and bring them flowers to apologize. It’s just such a weak gesture—and what better thing than to be on this furniture embodiment of a woman?

I can’t get over these fingers in the bouquet.

Belanger: They're crossed fingers, like she’s keeping a secret, or she’s insincere. Like when you promise something or say you’re sorry and hold your crossed fingers behind your back. It also directly references the broom figures.

Belanger: Despite our intentions, our work already has a lot of parallels—it’s already in conversation. We also have the same birthday.

When's your birthday?

Belanger: May 27th.

So, you’re a Gemini? That's kind of perfect since you’re kind of like twins.

Belanger: The light and the dark.

Who’s light and who’s dark?

Belanger: Well, I’m silver and she’s black—just appearance, though. On the inside, we’re both.

I love all of your still lives, as well—all of the fruit.

Belanger: I made my fruit sculptures inspired by Emily.

Smith: Last year, I made a painting with a specific frame. A lot of times, I paint a frame or border element in my work, which makes the painting sort of self-aware because it shows the boundaries, and these boundaries in our world are often invisible—it’s a way of rendering them visible. Art history is a boundary—all the boundaries of agency. So, I did this smaller painting of fruit last year and when I painted the grapes, I made them hang out over the edge of the frame, and I couldn’t really stop thinking about that as an important moment. Then I realized, 'What if I enlarged that scene, took away the painted frame and made that frame the shape of the painting itself?'

This arched shape at the top you see a lot in 19th century paintings, like sublime landscape paintings and symbolist paintings have this curve—even Casper David Friedrich had this curved top. So, basically, I kind of wanted to do my own version of a sublime landscape, but instead of it being great land of Manifest Destiny, it’s just an incredibly large bowl of fruit.

It’s not even a bowl—it’s literally a landscape.

Smith: Yeah, it’s like, 'Where’s the end?' Perhaps there’s no end—maybe they keep going. Fruit is so suggestive and metaphoric—they represent the body, they’re sexual and they can be very funny.

Above: 'Well Appointed' and 'Daily Adoration' (detail) by Genesis Belanger.

You’ve also included the peach, which has taken on new meaning as an emoji...

Smith: Right, that’s true! Actually, I left the banana out on purpose. I have done bananas in the past, but this time I thought it would be too far into emoji-land.

It has a color scheme as well, because of the lack of the banana—it’s very purple and green, and they’re so circular. So, a banana wouldn’t make sense, aesthetically.

Smith: The other thing with this painting is the overall lighting situation, where the main light is behind the fruit, which gives it this weird sense of forever-ness, like it could keep going. I almost like to think that perhaps it’s what’s on the other side of the window in ‘The Drawing Room.’ There’s something so satisfying about the grapes breaking the frame and dangling—a bunch of friends have made the joke that they’re almost like testicles—just balls hanging from the bottom of the painting.

Belanger: If you think about those Manifest Destiny paintings too, they were talking about man’s agency over all of the wild land—it’s there to be reaped, and this is almost an exaggeration of the idea of a reaping.

Smith: That’s funny, I almost called it ‘The Reaping,’ but then there’s a movie called The Reaping and I was like, 'Nope, can’t call it that.'

But Genesis, you do have bananas in your work(s).

Belanger: So, then my base is kind of that same idea but grasping all the fruits—just hoarding them. I love fruit because it’s this way men talk about women. Like, 'She’s so ripe,' and it’s a reduction of a woman using fruit, and it’s absurd, and ridiculous, and insulting, but also, hilarious—I think about that a lot. The banana is really important to me because—I don’t know if you've noticed, but in Ms. Pac-Man the banana is worth as much as all the other fruits combined. The banana is the patriarchy in the Ms. Pac-Man game.

Do you play Ms. Pac-Man a lot?

Belanger: I used to be sort of obsessed. Also, if you think about it, Ms. Pac-Man is just Pac-Man in drag. It’s like, drop a bow on it, now it’s a girl! I actually made a video of Pac-Man magically transforming into Ms. Pac-Man by eating lipstick and a shoe. But the thing about food that’s so true is that it’s a metaphor that’s used to dehumanize anybody who’s the object of dehumanization, especially racially, when they talk about skin colors as if they were food.

Smith: Like, 'She’s mocha,' or 'She’s vanilla.'

Belanger: It reduces someone into just what is consumable—it turns them into a consumable thing.

It’s desire—food and sex are like a hunger.

Belanger: The sandal with all the fruit in it I call ‘Swollen,’ and it’s like you’re stuffing as much consumable stuff into this tiny space until it’s bloated.

It’s cool, too, because the flowers and fruit decay. So, they’re going to fall apart.

Belanger: Right. I also think about our obsession with youth all the time. I turned 40 this year—Emily is actually a year younger than me—and I would never give one of those years back.

I would never have guessed.

Smith: I don’t know if we talked about this, but I painted the rings from Genesis’ finger sculpture on Medusa’s fingers, and I was just thinking about how when you look at Medusa, she turns you to stone, and all of the sculptures are made out of stone.

Belanger: That’s why we needed her—before, she was going to be just the broom. But the giant fingers are the biggest ceramic piece I’ve ever made. I really love it when a portion of the body or an object becomes a stand-in for the body, and these fingers really started to feel like legs to me. The broom is a person, this is a person, it could be two people—it’s the Gemini. I hadn’t even realized that.

Smith: We’re geniuses.

'A Strange Relative' is on view at Perrotin through December 22, 2018.

All images courtesy of the gallery.