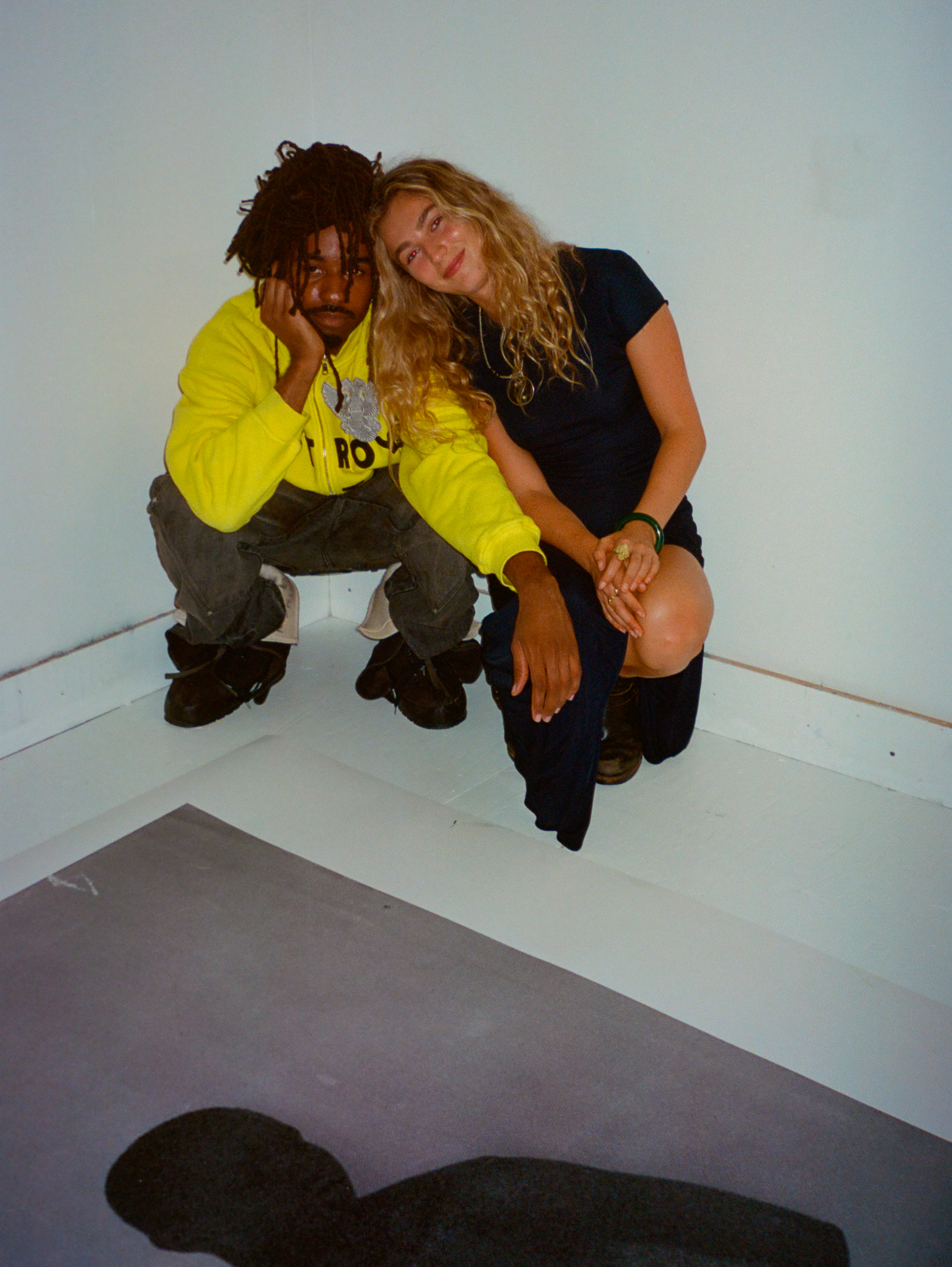

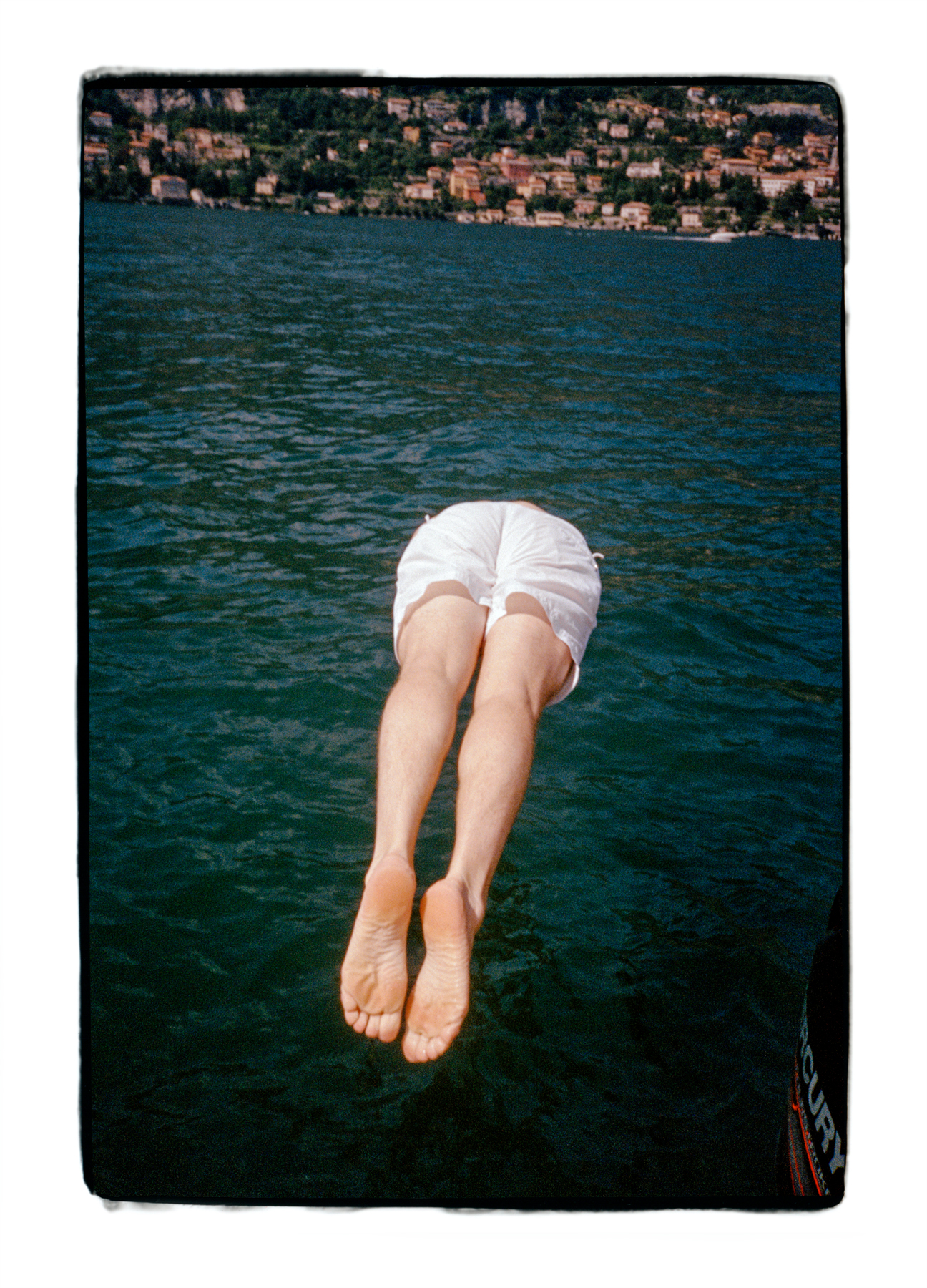

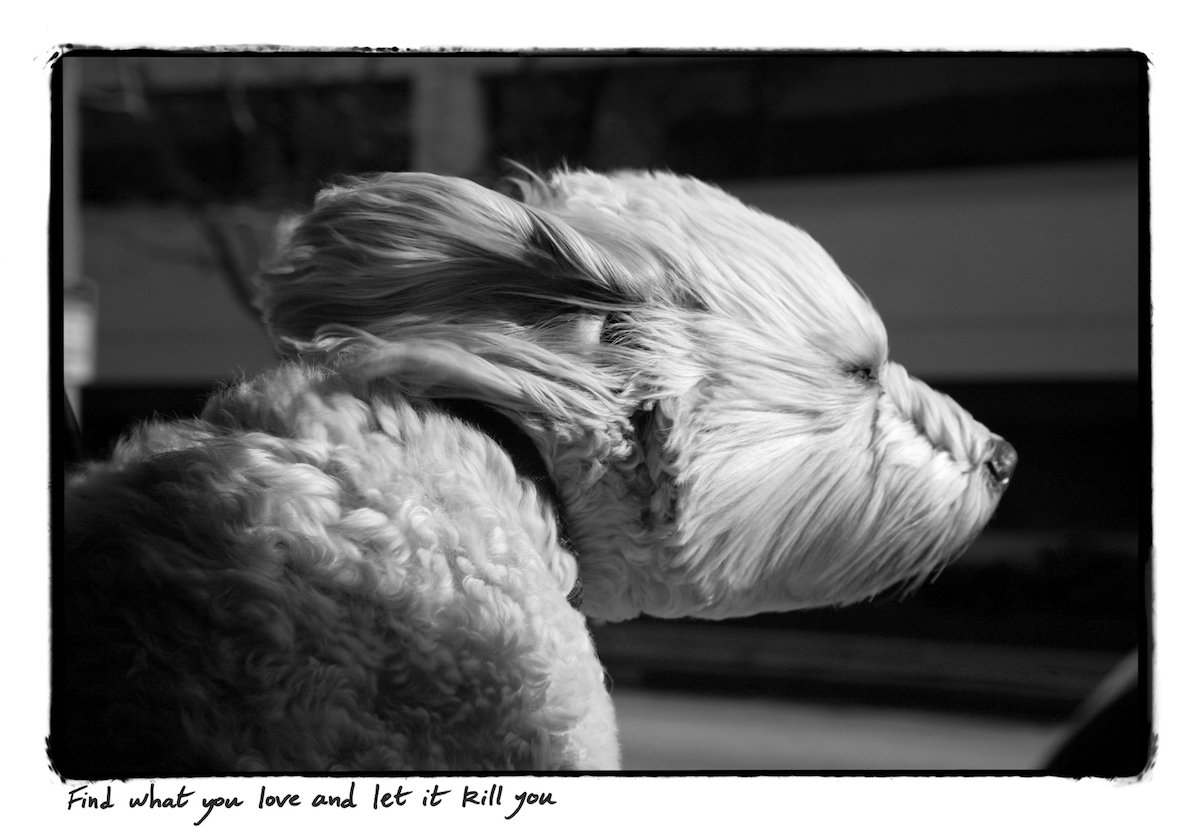

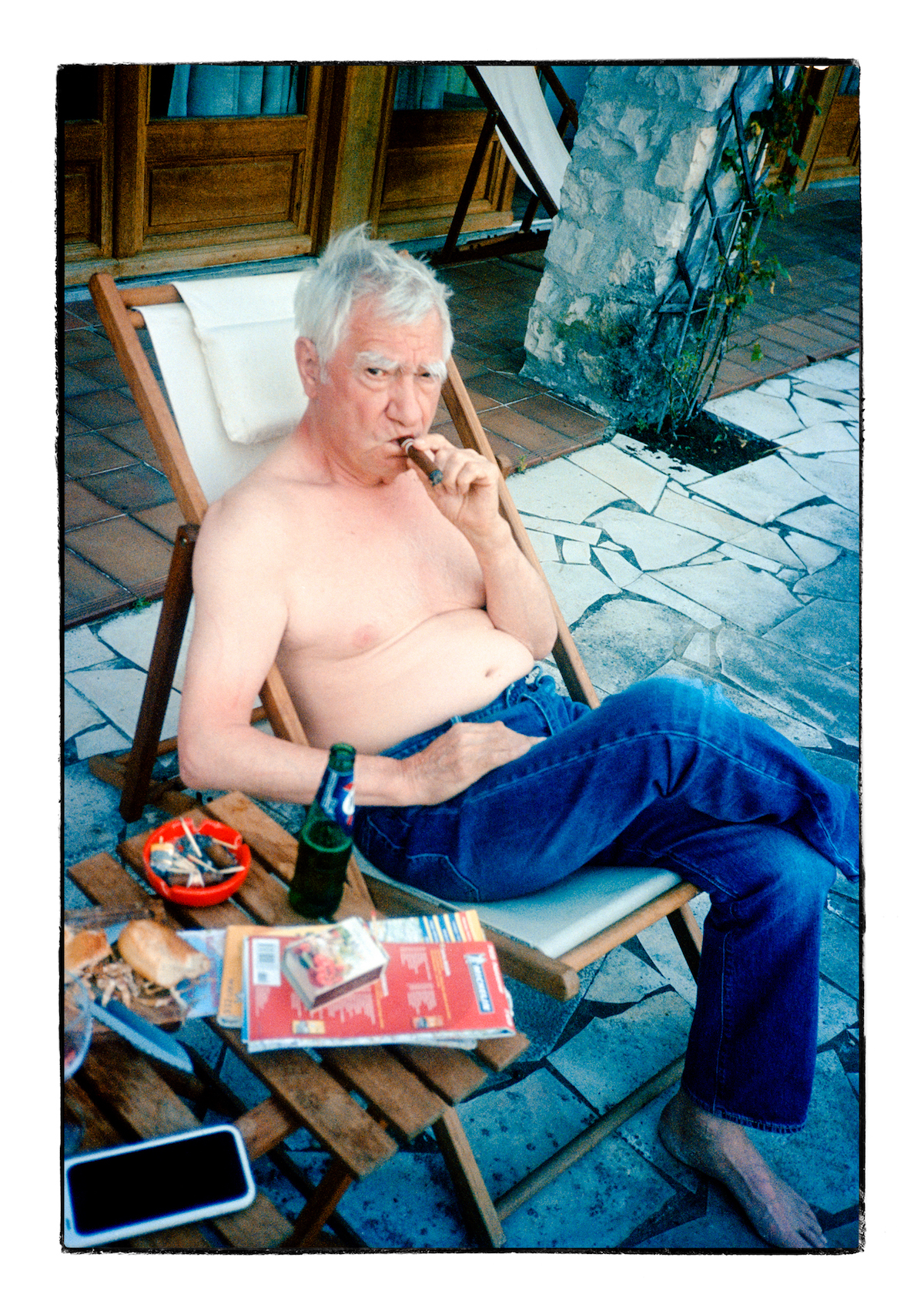

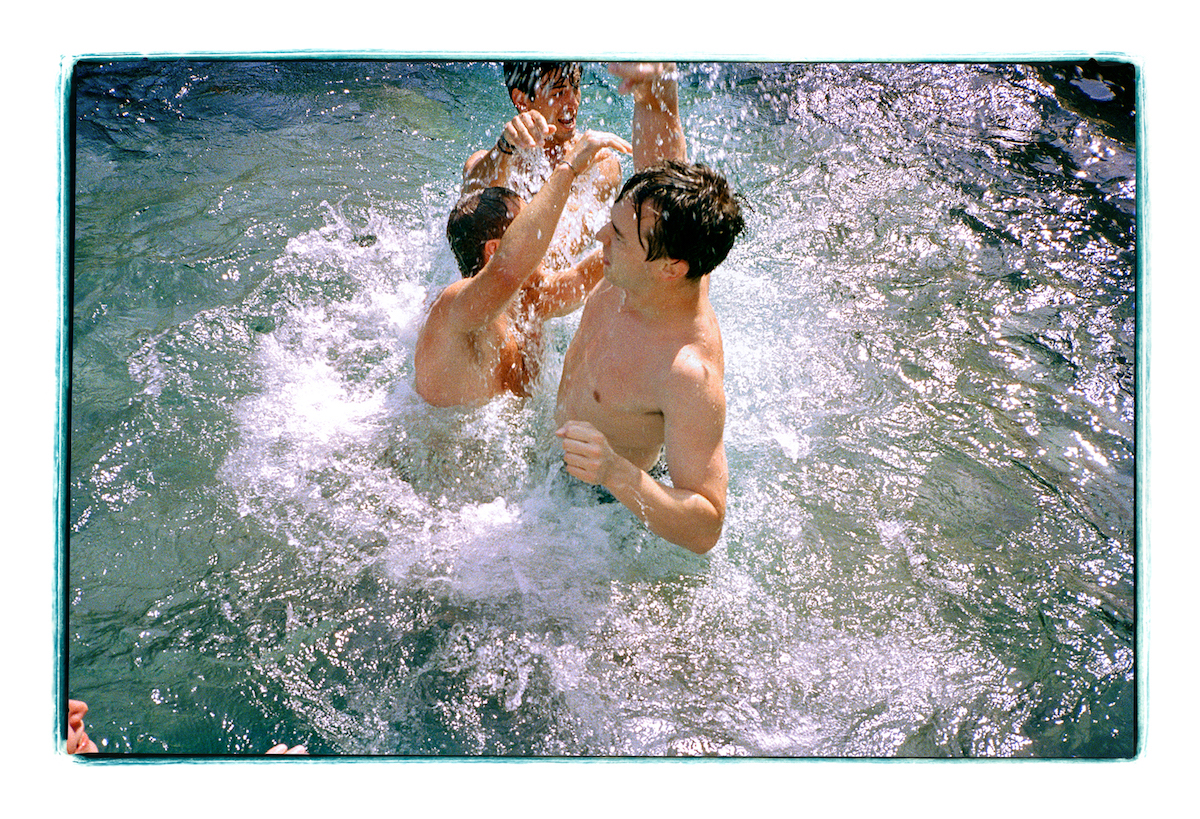

Wages of Sin

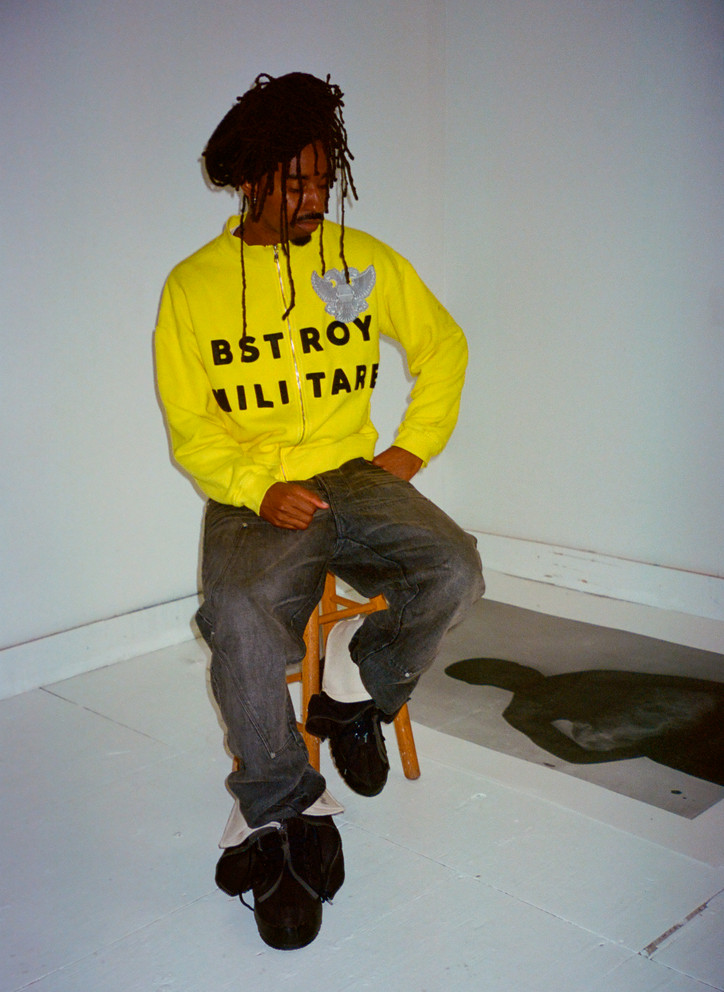

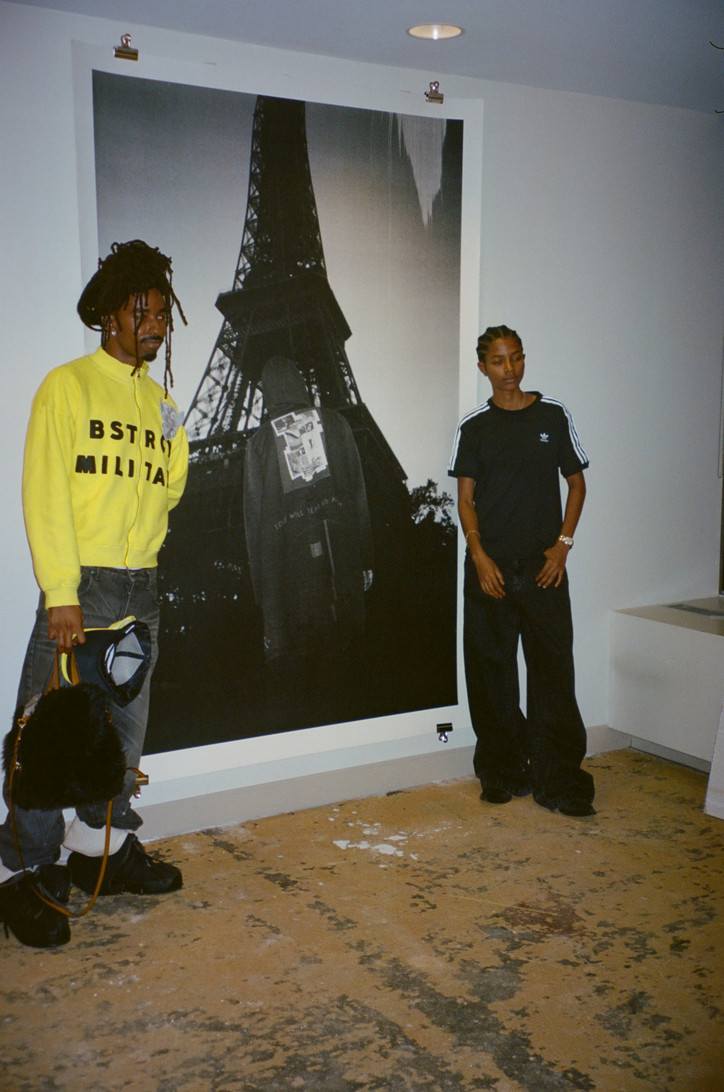

Remy Lagrange’s photo series, “Wages of Sin,” is on view at Milk Gallery as apart of adidas Showcase X through July 29.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Remy Lagrange’s photo series, “Wages of Sin,” is on view at Milk Gallery as apart of adidas Showcase X through July 29.

Berlin-based magazine 032c, which has long blurred the boundaries of a traditional publication with its extensive line of garments and apparel, launched a new, permanent, gallery space. Through its first show “Productive Narcissism,” artistic directors of the gallery Claire Koron Elat and Shelly Lea Reich insert themselves into Hugo’s ever-so-relevant dialect, challenging the contemporary conventions of a “publication” while addressing the self’s relation to re-invention.

In what ways will the gallery distinguish itself from the publication?

Claire Koron Elat— The gallery is part of the 032c universe. While the magazine is the nucleus of this universe, it expands into different realms – the ready-to-wear, residencies, exhibitions, and now the permanent gallery space. The gallery is an organic expansion, and at the same time, it questions the future of print publications. What are the alternatives to traditional ways of working in editorial? In our current state and time, flat images and digital are being highly prioritized; the gallery is also a response to that cultural shift.

Shelly Lea Reich— Our first show touched upon this topic of reinvention specifically, but it also reflects the publication and connection to redesign through the written word. We have worked with all of them in the past, which was a conscious decision to further and establish a long-term relationship with them. The gallery will be about establishing and furthering those connections, too.

You will be operating under a “semi-traditional model.” Could you define what this implies in practice?

CKE— It’s called semi-traditional because we want to start without a representation model: the gallery is officialy open and we have a running program, but we’re not yet representing any artists. It’s considered traditional because we have openly communicated that this is a commercial operation. We’re selling the art, and–while deeply interested in providing cultural value–we’re trying to make a profit.

But so is everybody, although desires of profit margins may differ. The business model under which art exists is hard to escape but easier to manipulate.

SLR— It is. And, in comparison to fashion, it’s something that the art world prefers not to talk about. Both Claire and I come from a background in the arts, meaning that we know the sensitivities in this scene, and how to address them with collectors.

Cezary Poniatowski, Reverse Prophecies, 2021. Ser Serpas, Alice (Language) Praxis 4, 2024.

Jon Rafman, 2024.

How might the “sensitivities in this scene” differentiate, given the gallery's location?

CKE— 032c was founded in Berlin and therefore has a deep connection to the city and its creative class. In its history, themes, and ethos — while simultaneously being hyper-international — 032c is deeply tied to the city; It made sense to open the first permanent gallery here. Joerg [Koch] has been organizing shows for decades, back when he had the old office at Brunnenstraße and then in St Agnes Furthermore, Berlin is a great place for welcoming “novel” projects because the scene is relatively open to finding newness in its traditions.

SR— Berlin has established itself as an important player in the art scene. Many galleries in the city are showing exhibitions at a really high level with a real in-depth intellectual curation, and as the city is still considered a relatively large city, but with a more affordable economic structure, we find it quite accommodating for new establishments. This transition of Berlin becoming a dominant cultural city in Germany and also in general is particularly notable in the context of galleries that have migrated from Cologne, such as neugerriemschneider and Galerie Buchholz, which expanded here in the 2000s after the fall of the wall - there has been a resurgence in Berlin's cultural landscape. At the same time, there’s still room for new initiatives to rise.

CKE— So far there hasn’t been any criticism. Probably because we’re not trying to portray the gallery as something that it isn't. We’re not a non-profit or charity foundation. We’re a gallery that, just like any gallery that travels too fairs or simply organizes exhibitions, is trying to sell what you see.

With the program we want to draw attention to the hybridity of the creative industry, and specifically that of art and fashion. Artists have always collaborated with mediums outside of their personal “traditional means,” or with other artists, or with fashion brands. Likewise, fashion brands have been inspired by artists throughout time. This is nothing new. That being said, what’s recently frowned upon is the idea that the more hyphenate you are — a DJ, a photographer, an artist, a director — the less focus or authority you hold over your chosen practices. I’m not bringing this to the table to make any judgement, but rather the opposite. Shelly and I have had a longstanding vision of reframing this hybrid intellectually. 032c Gallery will provide that. It will welcome experimentation.

The space is re-thinking the means of a magazine, while the exhibition itself is also commenting on the theme of reinvention. Through Boris Groy’s essay, the show investigates how “we are required to constantly re-invent ourselves,” thereby placing us in a permanent state of uncertainty. Who places this obligation upon us?

CKE— At the end of the day, it's not an obligation. It’s as philosophical and controversial as the question regarding free will. I would argue that you put this “obligation” on yourself, but doing so almost just by being part of contemporary society, especially in creative industries where one is “required” to reinvent to stay relevant. It only becomes dangerous once the speed of these reinventions reaches a constant. Endless adoption leads to uncertainty because that's where the core of oneself might get lost.

SLR— I think “requirement” here could be quite positive rather than negative. It’s very freeing to have these possibilities to reinvent yourself constantly. And it's something that's quite exciting. To be able to access a new version of oneself is to interact with different cultures, ideas, and expressions. It’s all part of a larger game. A good example of this is Amalia Ulman. We exhibited another work by her recently “excellences & perfections,” which recently celebrated ten years. In it, she intentionally adopted the role of a hyper-glamorous woman living a very lavish public life. Her friends and close circle quickly became confused with what was real and what wasn’t, but what’s fascinating is that so did Ulman, too. She explains how she got lost in the making, and confused her personae and personality for each other.

Lukas Heerich, Untitled, 2024.

Re-invention can become dangerous once the means of it is in the hands of the wrong people. And given that a lot of reinvention, as with Ulman, takes place in a virtual space or as a response to virtual hierarchies, does it not pass the risk of unregulated manipulation?

SLR— But you also have the freedom to manipulate the tools in return. As you are aware of these sets of rules, or your role as a user, that's where it becomes playful. I think that’s what’s specific about our times, that it’s easier if not even easy to get access to tools that weren’t accessible before. Circumstances under which self-creation is not only possible but infinite.

CKE— Humans were the one who built the algorithm. It’s not like we are being controlled by this otherworldly superpower. It’s not the man versus machine here—it’s you versus yourself. It’s a mechanism that we created and something that we also still control. Of course, we’re not always conscious about what we consume or in the ways in which it affects us. But once we take time to reflect upon it, question it, question ourselves, is when we get control over our self-reinvention.

How often do you reinvent yourself?

SLR— Good question. I think that we reinvented ourselves with the gallery. It’s been a shift in mindset.

CKE— For me, personal reinvention it's not so much about reinvention but rather a progressive invention. What about yourself?

I got a new haircut. A new look is always a reinvention because suddenly you are perceived differently. I think of reinvention as an external, social act. It’s dependent on the response, even though Narcissus might suggest otherwise.

Hugo Comte, 2024.

“Productive Narcissism” will be on view at 032c Gallery in Berlin until October 8th, 2024.

For her solo exhibition Open Arms at Anat Ebgi Gallery, which opened on Friday September 6, Dicke debuted a new body of works that continues her exploration of the signs and symbols shaping how we view the female form. In Open Arms, she expands her focus to include men’s fashion ads, art catalogs, and art history books. What connects these different interventions into modern masterpieces and male model photoshoots is a defiance of the convention that reduces women to passive objects of desire within images. At the same time, Dicke embraces the human tendency to project desires onto these images, making her revisions both sensual and fluid. Open Arms can be seen as a love letter to the art of self-representation, while critically examining what it means to engage with these representations.

Hi Amie. I’m really excited for your show at Anat Ebgi Gallery. I want to start by asking about how you first came into the art world. You were a model in New York in the early 2000s, right?

This story has become a thing of its own. I did live in New York for a year and a half as a starting artist to follow my then fresh love, but I did not model. I only worked as a teen model in Rotterdam. I was too shy to be a good model. The camera made me feel very vulnerable. I love fashion. Still, I prefer to stay on the other side of the camera. In Rotterdam, I also made sculptures and got some attention fresh out of art school. Somehow, making sculptures did not feel viable because of how masculinist it is in Europe. Instead, in New York, I found myself through all the imagery I saw on the street advertisements and magazines. Everything felt insanely new for me. I even learned how to navigate the subway because of these huge Calvin Klein posters. So, I started drawing on them and cutting them away.

What made you particularly attracted to images of young women found in fashion advertisements and magazines?

I am fascinated by how images of thin, young women are constantly pushed onto us. They often link back to archetypes like the muse or the Holy Virgin. I was studying old portraits of Mary and realized how her posture or gaze can reveal esoteric meanings. The same thing can be said about the innocent young girls I see in fashion imagery.

And you mostly construct images of faceless women in elaborated contexts, be it clothing or setting, which can be quite telling. I am curious as to why you are not fully denying our access to these women’s psychology.

My working process is full of discoveries. I rip pages out of magazines or art books, scan them and blow them up, and reproduce them on archival paper. Throughout the process, the images speak back to me, hinting at what to leave untouched and what to scrape away. In all cases, the images end up having this dualistic quality, somewhere between absence and presence. The women in my works reject the viewer's desire to identify with them but at the same time demands more attention. I find this doubling gesture very alluring, as if they took on the eternal quality of historical portrait painting.

Amie Dicke, Zeitgeist, 2024. Courtesy of Anat Ebgi Gallery.

Amie Dicke, Salomé, 2024. Courtesy of Anat Ebgi Gallery.

I also noticed that in this new body of work you have started to work with images of male models. The figures in Zeitgeist (2024) and Salomé (2024) have a more masculine build.

I realized there is something about masculine features, either square face shapes or bigger shoulders, that lend well to my abrasion. The Salomé piece is close to my heart. It was originally a magazine shoot of a male model standing in a museum, with several paintings behind him. I have always been interested in looking at the photographic reproduction of paintings, thinking about how they come to us and what we learn from them. While looking at the image, I saw a nude painting in the top right corner, with her face perfectly cut off from the frame. However, I can still identify her as Salomé by the antique placard placed on the painting’s frame. I was thinking about censoring the title but soon realized how perfect it is in relation to the faceless male model in the front. Salomé famously requested the beheading of John the Baptist.

Amie Dicke, The Bathers, 2024. Courtesy of Anat Ebgi Gallery.

Amie Dicke, Nude, 2024. Courtesy of Anat Ebgi Gallery.

You’ve also started working with the history of Western art itself. The Bathers (2024) and Nude (2024) strike me as full-frontal assaults on their source materials, Renoir’s The Large Bathers (1887) and Manet’s Olympia (1863) respectively. What is your motivation for taking a revisionist approach to these paintings, which are so important to the tradition of European modernism?

I must confess I find it very easy to attack The Large Bathers. I am not really a fan of that painting, and I wanted to question its position within art history. Painting is an act of mythmaking, and I am annoyed at how The Large Bathers reinforces the trope of naked young women being spied on from a distance. I want to see these bathers in a different light so now they are drowning or trying to survive in a sea of lipstick. With Olympia, I am curious about what remains of a reclining classical nude if I take everything away. In the end, Nude takes on a Cubist tradition. Also, you can see a page number on the edges of Nude because I appropriated a reproduction of the original painting from an older magazine. The colors are a bit off, which made my sandpaper intervention more interesting.

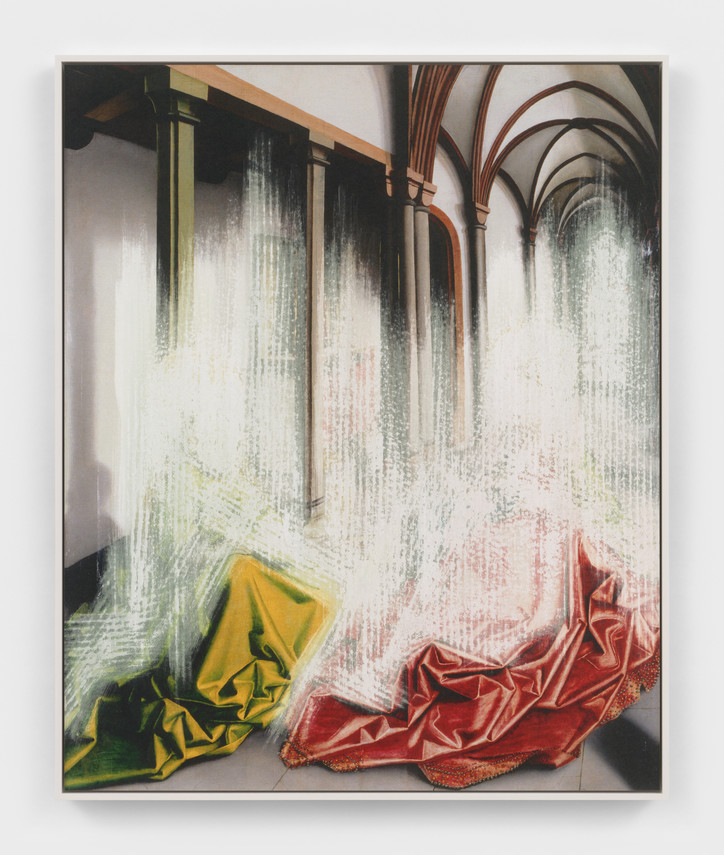

Amie Dicke, Church, 2024. Courtesy of Anat Ebgi Gallery.

Your preoccupation with questions of authenticity and authorship feels most prominent in Church (2024).

Yes, Church is based on the reproduction of a painting I found in a catalog. In the painting, there were two praying figures in a church. I am intrigued by the beautiful, dramatic pleats they are wearing. Once I erase the girls, the pleats take on a very spiritual, almost ghostly quality. In the left corner, you see shadows originally belonging to one of the figures, but now the shadows make the pleats come alive. I was born and raised in a Pentecostal church, so the Holy Spirit is something I am very familiar with.

I read somewhere that your studio is in a church. Is that right?

My studio is in a formerly Catholic church in the center of Amsterdam. I am renting one of the two sacristies next to the altar. The church was secularized but they still have services with another group of Christians on Sunday mornings. Sometimes the church functions as a voting station. Patti Smith performed there too. I sometimes climb onto the altar to find a better Wi-Fi connection. A lot of the days the church is empty, and I am just alone in the building.

Are you still religious?

No, but I still care about the devotional labor in my works. Devotion is very beautiful. I want to be able to train myself to lean into the inner spirits of great literature or painting, and to lean into myself and others. Those emotions and feelings I felt in the Pentecostal church still hold meaning to me. Also, once you have learned how to pray, it stays with you.

I imagine working in a church easily brings out those feelings too.

Yes. Those feelings are everywhere with me. It is more in my heart. Growing up as a young woman in a Pentecostal church and in a very Catholic country, I have always been annoyed by rules and power imbalances within the church. It’s always a man standing there and preaching. Not to mention the Madonna-whore complex. In the Bible, a lot of the female characters are usually sidelined or just presented as a temptress. I want to represent them differently.

Are you then freeing women from the confines of great books and modernism?

I’m not sure if I am freeing them, but I am freeing myself. Maybe at a certain point I will be really free, then I am curious what I am going to make. Too much freedom is panic, right?

You can check out 'Swallow the Lake' between now and October 4th.

How did growing up in Atlanta impact your outlook on the world of art and what it means to be an artist?

Growing up in Atlanta I was only ever surrounded by music. Which is sick because at a young age it was very inspiring to see other people near my age so independent and unafraid to put themselves out there. Looking back now, this showed me that it’s our duty as artists to think outside of the box and to produce new concepts and spinoffs of old ones in order for society to continue evolving.

How do you see your work evolving after this exhibition? Are there new themes or techniques you’d like to explore?

This was just the beginning for me. This show is filled with ideas that I've worked on for about three to four years that I was able to nurture and evolve overtime. As I explored the themes of this show, I found myself opening up the doors to a few new ideas that I'd love to dive deeper on. Now that I have my first studio residency at 99 Canal, I can’t wait to dive in and experiment with more mediums.

There’s a series of prints in this exhibition selling for just $250 each. Do you feel art should be made more accessible to people?

Most definitely. A major part of the show’s conceptualization has been about bridging the gap between multiple worlds. It honestly felt necessary to create something for the younger version of me. The version of myself that didn’t know much about art, but was curious.

Why did you choose to debut in New York and not Atlanta?

I think my background in music definitely played a part in this decision. When musicians go on tour they typically never start in their hometown. My plan is to continue my growth and exploration, so that my homecoming can be as impactful as possible. The contemporary art scene of Atlanta is still very niche, so I’d love to play a significant role in its growth and evolution. I just want to be ready.

What was the last thing you took a picture of?

My baby brother Tana. He’s my favorite subject right now.

Where in the world do you feel most creative?

Atlanta for sure.

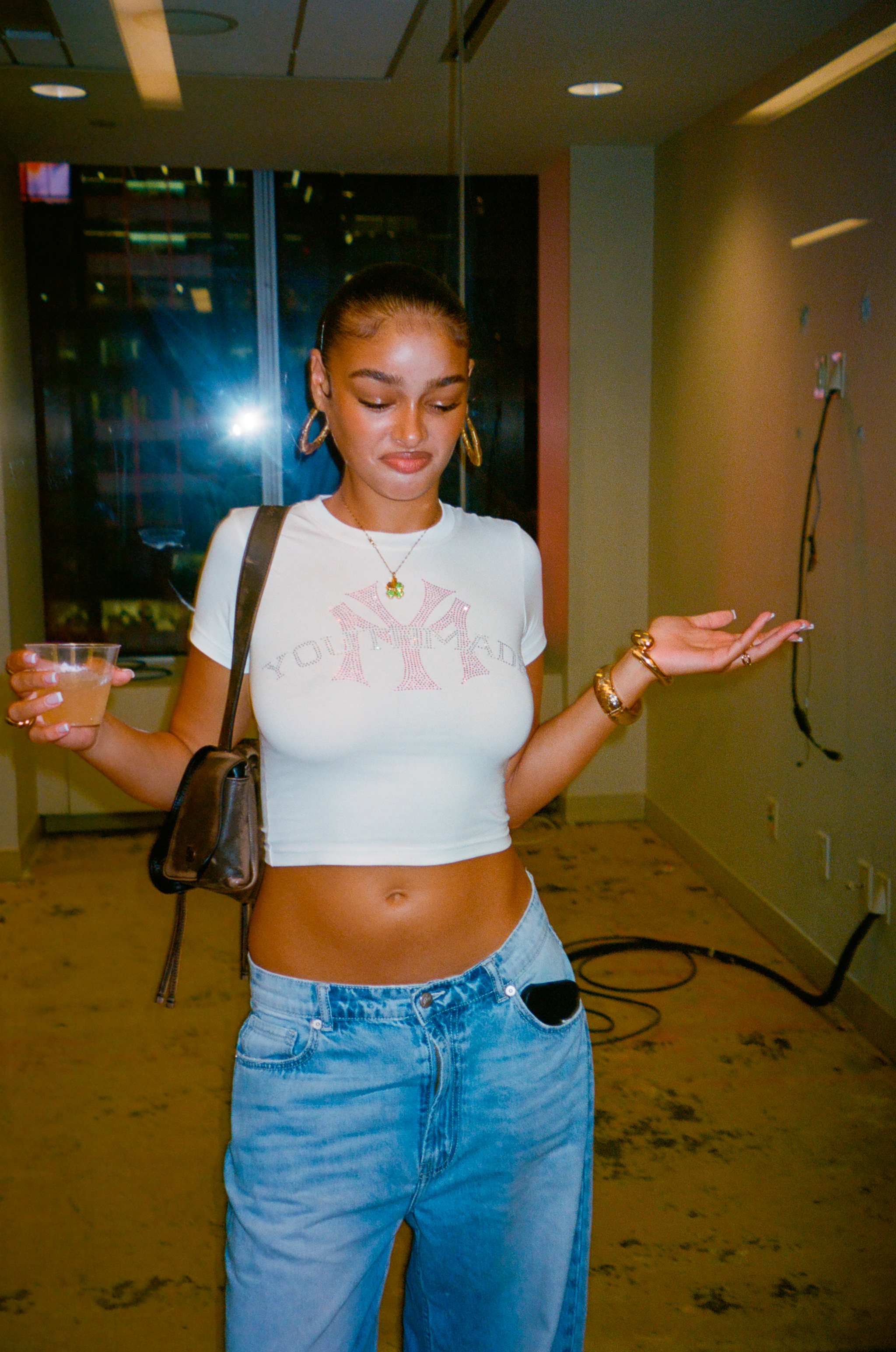

Who was the most interesting person you’ve taken a picture of?

Maybe Anok. She’s so sweet and always up to something cool. Frank Ocean was really cool too, we took photos then argued about gumbo.

How do you decide which stories or moments to capture? Is it instinctual or do you plan ahead?

A mixture of both. It really depends on what’s going on in my life at the moment. A lot of my subjects are very well known and are extensively photographed. As I’ve grown, I’ve looked to move away from that oversaturated style of celebrity photography, by moving a bit more selfish in a way. I prefer to show a moment of vulnerability and intimacy, that often feels like a reflection of myself. Most of my photos are self portraits exhibited through my subjects.

How has social media impacted the photography industry, and how do you use it to your advantage?

Honestly it has watered it down in my opinion. Images are now worth less than they were in the past. Everything is too accessible and fleeting. I think we share too much. One of my main goals with my work has been to create a stronger love and respect for photography as a unique art form by creating more physical works instead of just letting my images live online.

Are there any particular subjects or themes you want to explore but haven’t yet?

In my opinion I need to spend more time developing my skills as a painter, but I'd love to explore sculpture and architecture. I have also been doing some digging into my family history and one of my main goals in life is to connect the missing links to my family tree. I would love to incorporate that into my work at some point.