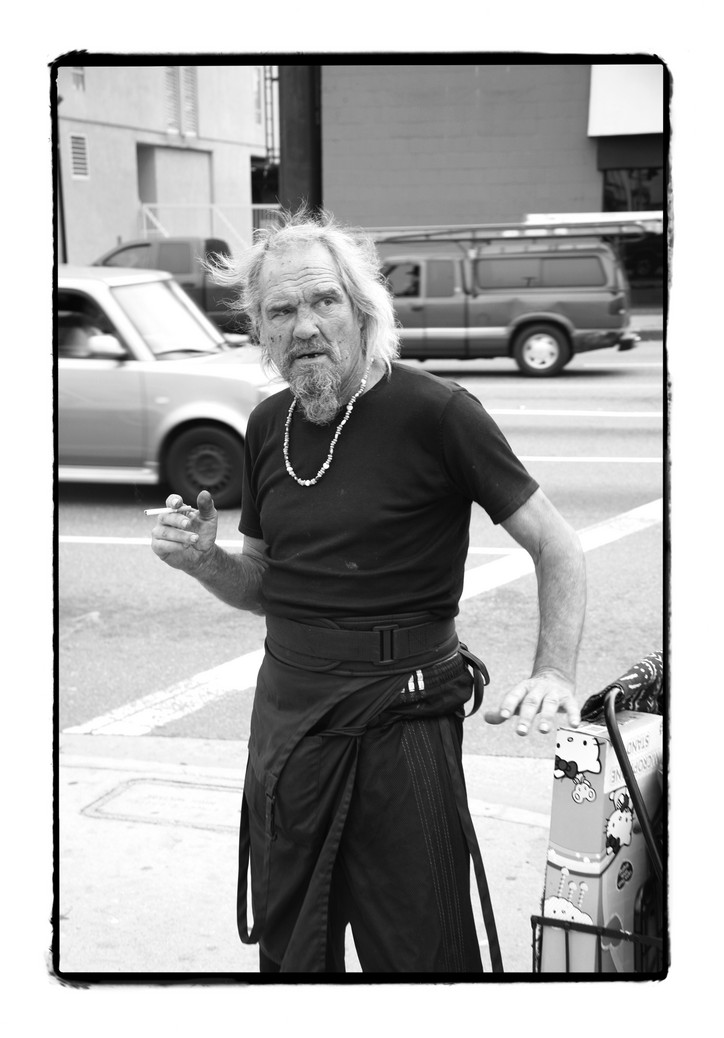

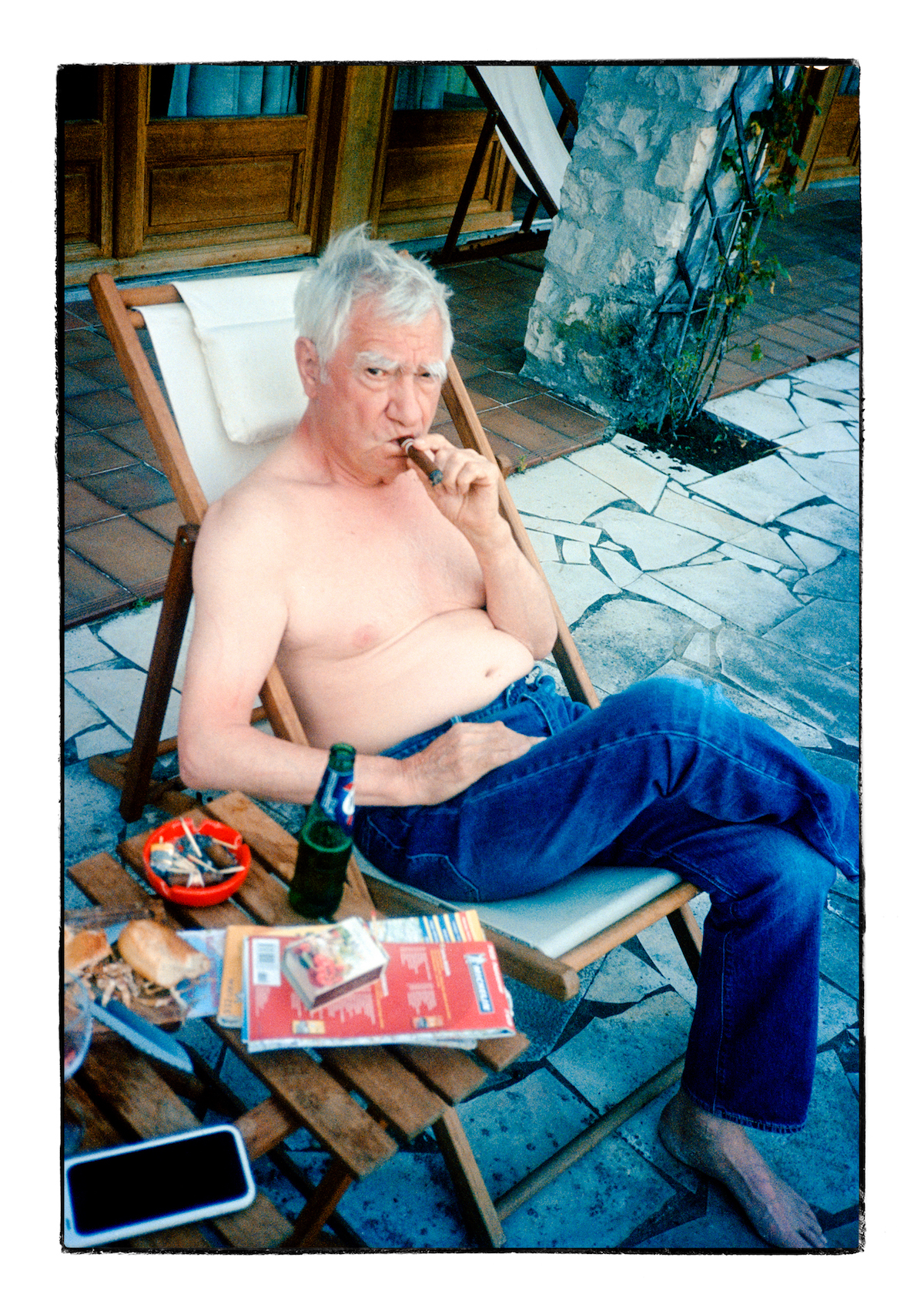

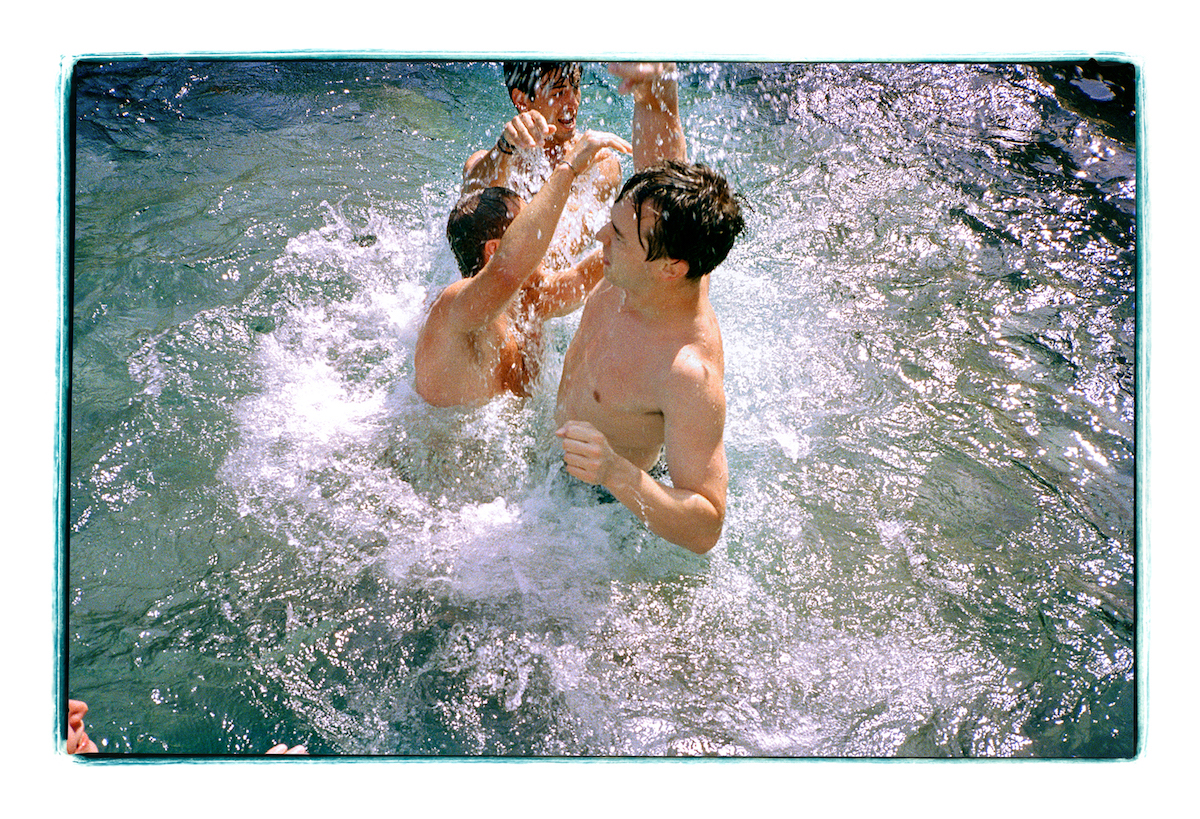

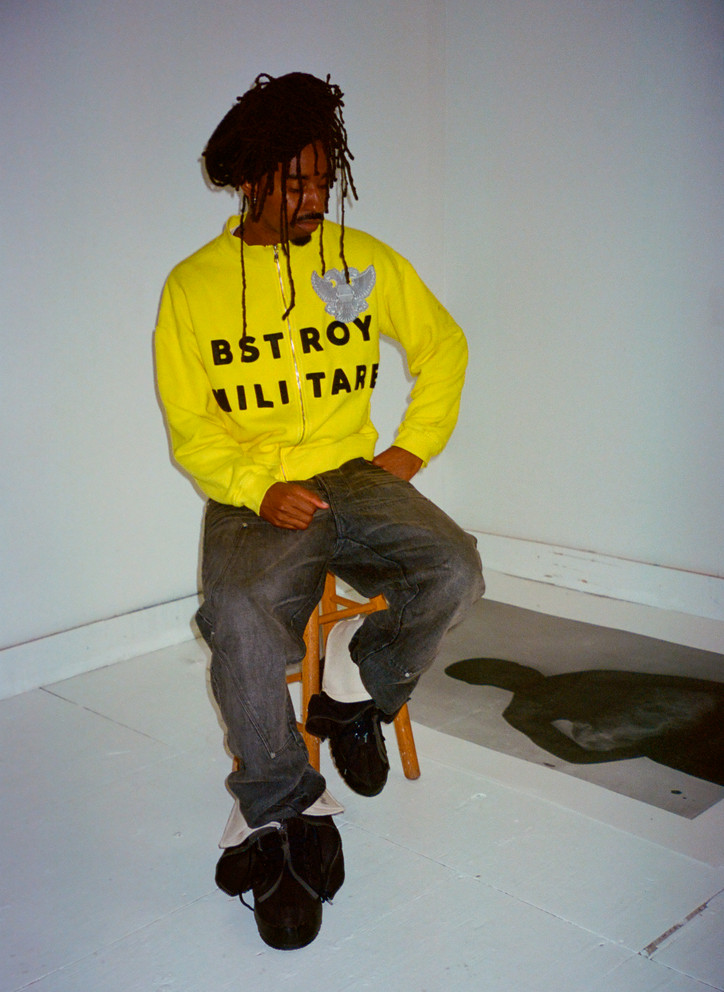

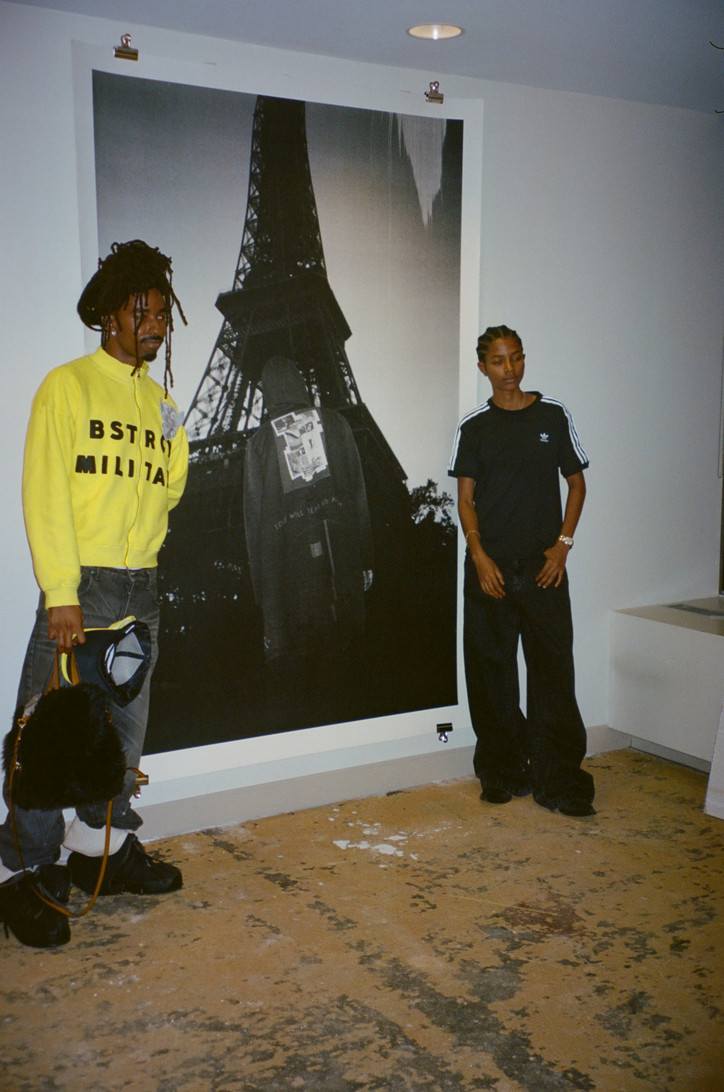

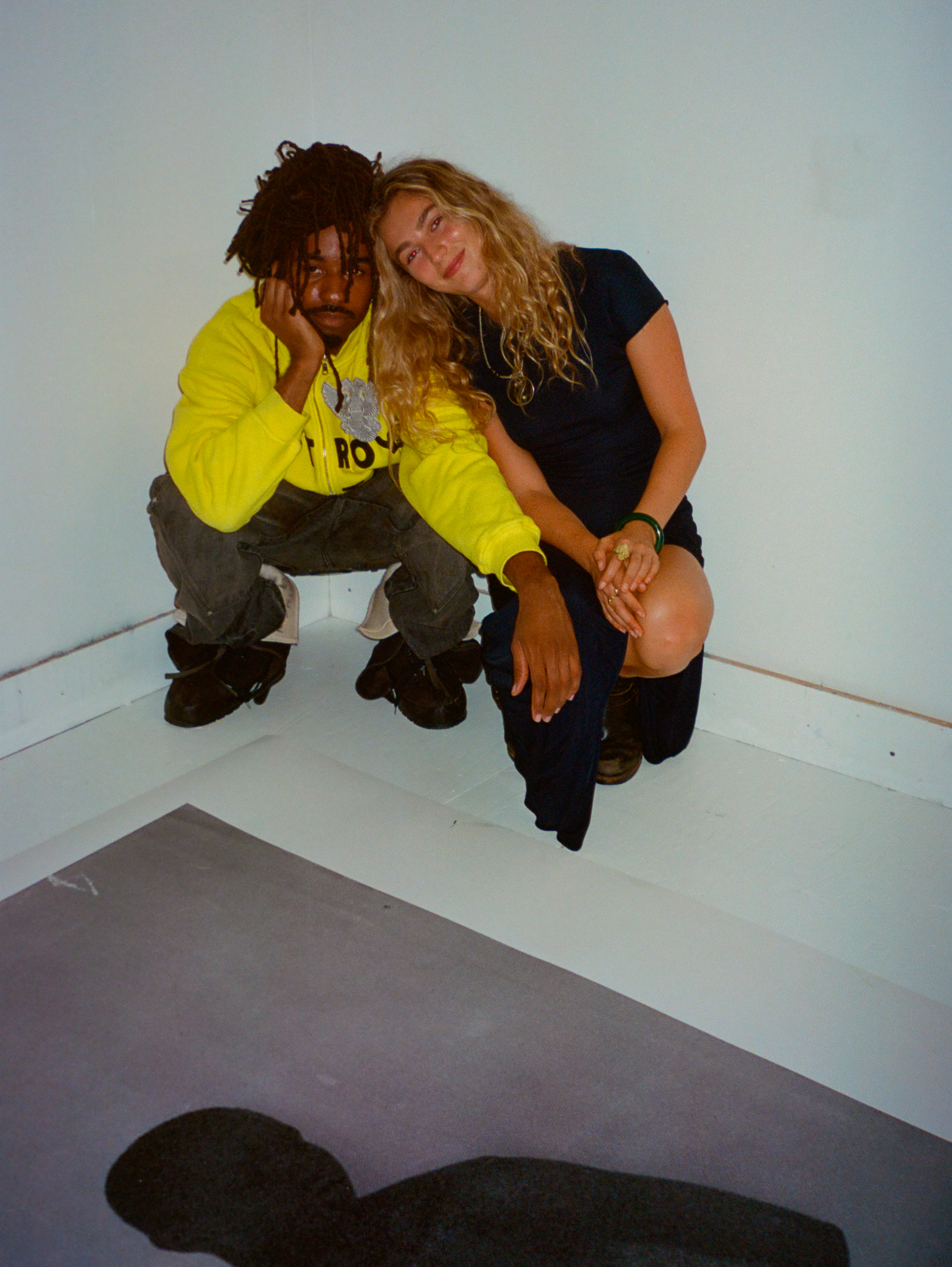

Wages of Sin

Remy Lagrange’s photo series, “Wages of Sin,” is on view at Milk Gallery as apart of adidas Showcase X through July 29.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Remy Lagrange’s photo series, “Wages of Sin,” is on view at Milk Gallery as apart of adidas Showcase X through July 29.

You can check out 'Swallow the Lake' between now and October 4th.

How did growing up in Atlanta impact your outlook on the world of art and what it means to be an artist?

Growing up in Atlanta I was only ever surrounded by music. Which is sick because at a young age it was very inspiring to see other people near my age so independent and unafraid to put themselves out there. Looking back now, this showed me that it’s our duty as artists to think outside of the box and to produce new concepts and spinoffs of old ones in order for society to continue evolving.

How do you see your work evolving after this exhibition? Are there new themes or techniques you’d like to explore?

This was just the beginning for me. This show is filled with ideas that I've worked on for about three to four years that I was able to nurture and evolve overtime. As I explored the themes of this show, I found myself opening up the doors to a few new ideas that I'd love to dive deeper on. Now that I have my first studio residency at 99 Canal, I can’t wait to dive in and experiment with more mediums.

There’s a series of prints in this exhibition selling for just $250 each. Do you feel art should be made more accessible to people?

Most definitely. A major part of the show’s conceptualization has been about bridging the gap between multiple worlds. It honestly felt necessary to create something for the younger version of me. The version of myself that didn’t know much about art, but was curious.

Why did you choose to debut in New York and not Atlanta?

I think my background in music definitely played a part in this decision. When musicians go on tour they typically never start in their hometown. My plan is to continue my growth and exploration, so that my homecoming can be as impactful as possible. The contemporary art scene of Atlanta is still very niche, so I’d love to play a significant role in its growth and evolution. I just want to be ready.

What was the last thing you took a picture of?

My baby brother Tana. He’s my favorite subject right now.

Where in the world do you feel most creative?

Atlanta for sure.

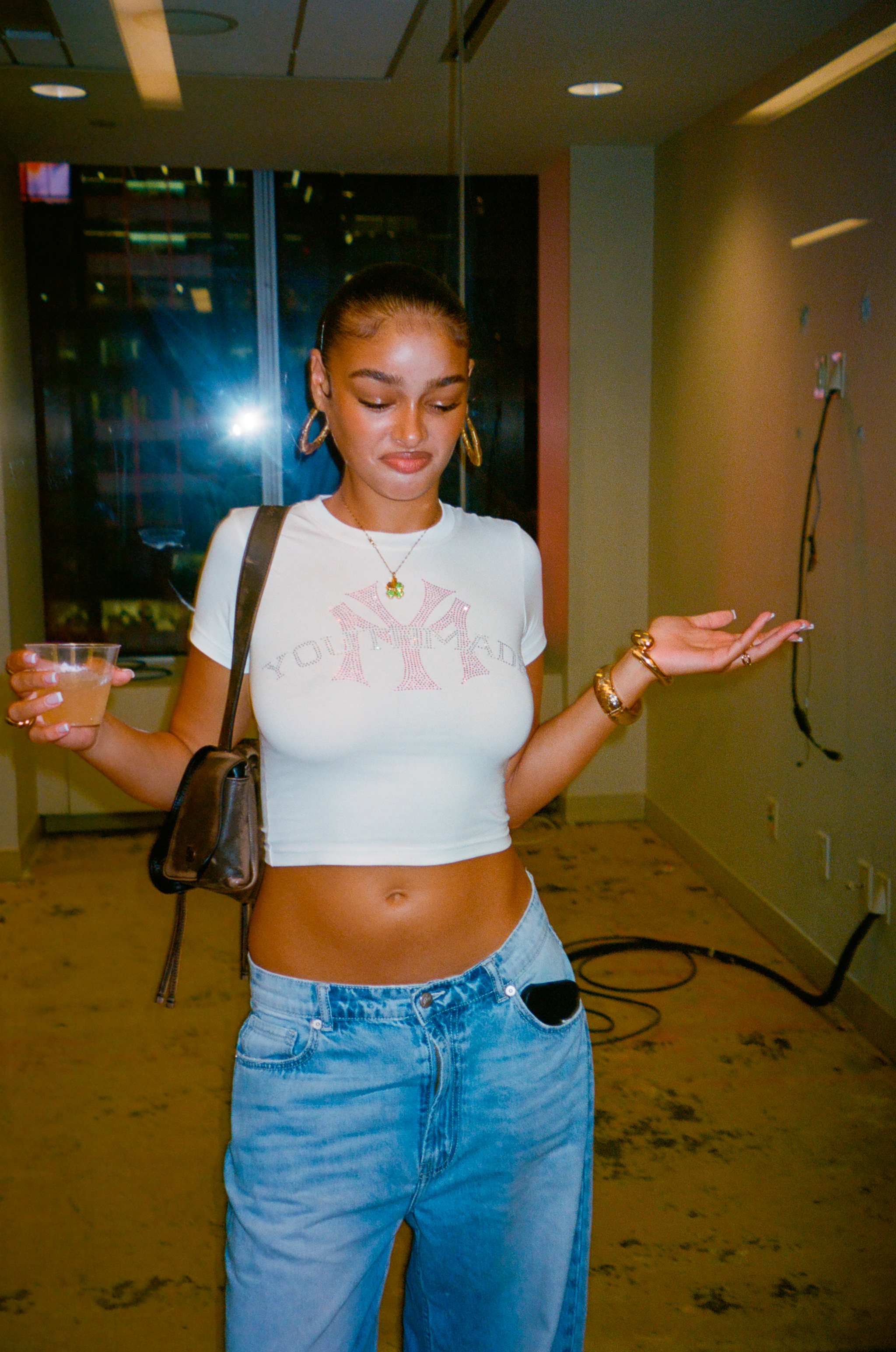

Who was the most interesting person you’ve taken a picture of?

Maybe Anok. She’s so sweet and always up to something cool. Frank Ocean was really cool too, we took photos then argued about gumbo.

How do you decide which stories or moments to capture? Is it instinctual or do you plan ahead?

A mixture of both. It really depends on what’s going on in my life at the moment. A lot of my subjects are very well known and are extensively photographed. As I’ve grown, I’ve looked to move away from that oversaturated style of celebrity photography, by moving a bit more selfish in a way. I prefer to show a moment of vulnerability and intimacy, that often feels like a reflection of myself. Most of my photos are self portraits exhibited through my subjects.

How has social media impacted the photography industry, and how do you use it to your advantage?

Honestly it has watered it down in my opinion. Images are now worth less than they were in the past. Everything is too accessible and fleeting. I think we share too much. One of my main goals with my work has been to create a stronger love and respect for photography as a unique art form by creating more physical works instead of just letting my images live online.

Are there any particular subjects or themes you want to explore but haven’t yet?

In my opinion I need to spend more time developing my skills as a painter, but I'd love to explore sculpture and architecture. I have also been doing some digging into my family history and one of my main goals in life is to connect the missing links to my family tree. I would love to incorporate that into my work at some point.

Of the three shows Mulrooney unveiled this weekend, Majić’s is the only one tied to the much anticipated PST ART extravaganza, spearheaded by Getty, wherein 70 museums and galleries between Santa Barbara and Palm Springs are staging shows that illustrate how “Art and Science Collide.” PST curators scouted Majić after his New York solo show “Nocturne” with Nino Mier last year, and asked if he wanted to join the program. Mulrooney is making sure it happens.

I stopped by Majić’s studio near the Jefferson L stop a month before “Dawning” opened, to see the show’s sixteen artworks before they left for California. It had been just several days since his wife had given birth. A sizable, small-scale replica of Megan Mulrooney Gallery crowded the canvases and cacti that line Majić’s studio’s walls and windows, to help him arrange the show.

While “Nocturnes” offered only monumental paintings, “Dawning” marks Majić’s return on the ever-swinging pendulum back to compact creations, which allow him to ride inertia more aggressively — and forge closer relationships with viewers. To call these works paintings doesn’t feel entirely accurate, but that’s how he refers to them. Their surfaces have a sculptural quality.

Motifs reappear. There’s a lone wolf who might be Majić, alongside a captain, a pilot, and an astronaut. Crystal waters pool in secluded spots, and glamorous parties rage in eras impossible to place. Every piece begins with a Photoshop collage. Majić shakes the same box of compositional elements culled from 70s advertisements and Japanese woodblock firework manuals alike. They come tumbling out fresh each time, and he works them over across layers.

Then, Majić draws his scenes on rough burlap canvases in colored pencils. These understudies turn out so vibrant that he finds them “crude,” so he paints atop them. Things get interesting when he mixes marble dust with oil and slathers a milky veil over that base. Next, Majić goes in with colored pencils and carves out flashes of his understudy, toeing the line between vivid and subdued. These surfaces embody the textures he’s portraying, whether that’s water or smoke.

It’s not a perfect formula. “I completely killed the whole image,” Majić says of “The summoning” (all works 2024). “I put so much of that gray layer on it — I was almost crying.” Fortunately, he turned the work around and returned to it as a new person — one who could resolve the work’s wriggling madness into one scintillating pattern. He considers “The inside” the final installment in this spotty story, like a brownout memory. There’s room for error. Is the figure on a couch or a coffin? Rushing water, or a 1980s carpet? In the subconscious, symbols can possess duplicity.

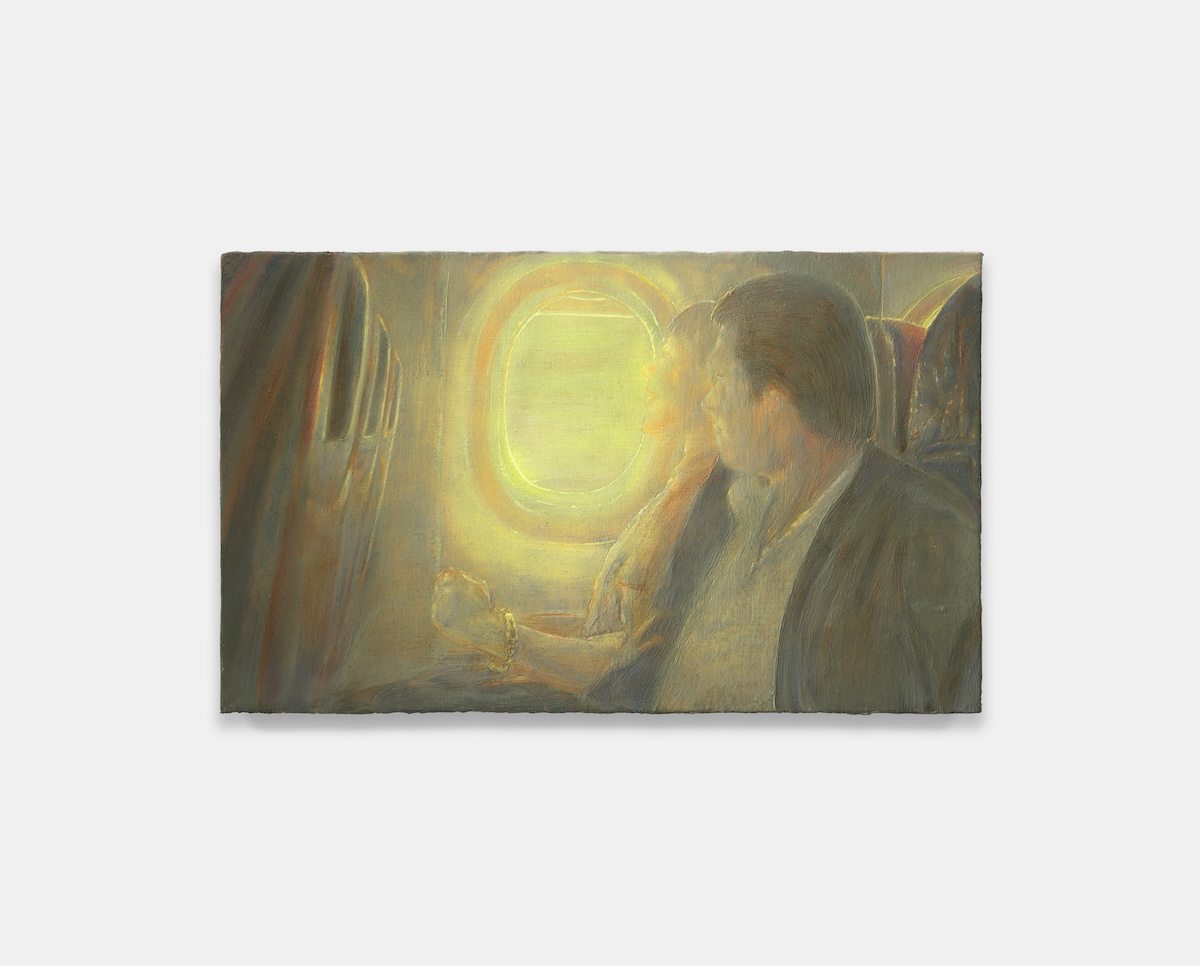

Majić struggled similarly against “You looking for you, me looking for me” and “The Distance,” a diptych that’s separated in “Dawning.” Parties are chaotic, but every detail on a plane is precise.

In the scene on the right, when they were placed together in his studio, a man and woman laugh next to a plane window. In the painting on the left, the man’s mouth is closed, and he’s alone. The plane travels the opposite way. These narrative markers invoke the viewer to invent stories.

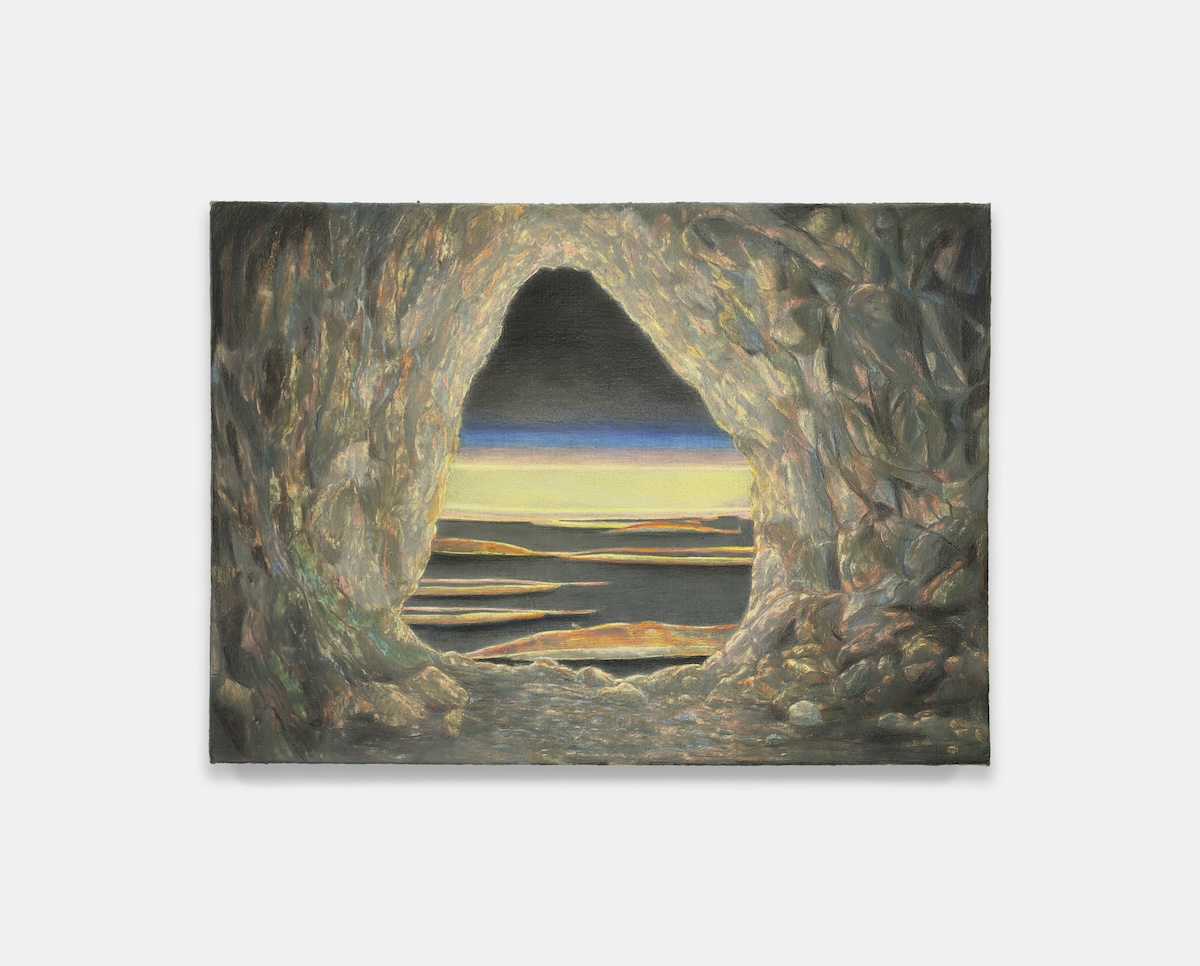

The most potent duo in this series frames either side of the entryway to “Dawning” like a secret little legend. Two cave paintings appear to depict dawn, and dead night. At first, they appear to illustrate a single evening. But, subtle differences between the landscapes beg the question of how much time has actually passed. That’s the trick. This series is really working with time. The sentence “all of these things happening at once” does still describe a concrete amount of time.

Speed dictates time, which stops at the speed of light. There’s your everything all at once. Of course, we don’t typically perceive the real situation. Our animal brains, engineered for survival, filter extraneous details — paring totality down to consensual reality. Not long after art mastered replicating that reality, art began interrogating it, initially through abstract expressionism. Today, it’s through psychedelic ambivalence, like how the orb above “I will not follow” might be a sun or a moon, that calling card of our era. Ambivalence pries the door open, offering entry into a work.

All the scenes in Majić’s latest endeavors could be happening all at once, across any number of places around the world. Such is the nature of consensual reality. In fact, Majić’s dark yet radiant aesthetic, perfectly suited to this moment’s escapist tastes, looks a bit like traveling at light speed. Science hasn’t figured out how to make a person move that fast yet. That’s what art’s for.

"Real estate is tough in LA," she explained recently, acknowledging the challenges while emphasizing her commitment to the artists and community she’d worked with for years. "I felt a responsibility to preserve what I had built that wasn't mired in scandal. I had created something great here — my kid goes to school down the road, I live fifteen minutes away. This is my home.”

Two of the galleries are reserved for solo shows, while the third serves as a curated collection, where an artist handpicks favorite works from their peers. For the solos, Mulrooney emphasized the importance of creating intergenerational connections, featuring 22-year-old painter Piper Bangs and 45-year-old Marin Majić.

In Bangs’ "Fruiting Body", you’re invited into a dreamy world where droopy pears roam between forest floors and clouds, waiting for the sun to pierce through. In Marin Majić's "Dawning", technicolor and marble dust glow on drawings of nightclubs, speedboats, and early morning plane rides.

"The exhibitions speak to each other," Mulrooney said. "[Both artists] have a world-building process that teaches us their way of seeing."

Meanwhile, "Saints and Poets", curated by artist Jon Pylypchuk, sparks its own conversation. "I love this idea of finding out what makes [an artist] tick," Mulrooney shared. "Who are they looking at, who did they go to school with, who is in their circle of artists? In the 16th or 17th century, you’d see these groups of artists referred to as a ‘School.’ 'Saints and Poets' is like the School of Jon Pylypchuk."

In Jon's "school", playful characters made of bronze-casted balaclavas spring to life, and a sculpture of entangled, human-shaped cotton feels so intimate you shouldn't be looking. (I kept looking.)

"I want you to feel good about what you saw," Mulrooney said. " Maybe you didn't like it, maybe you loved it, but you're still like, ‘Wow, this has been interesting.’"

In the coming months, the gallery plans to showcase other former-Mier artists before transitioning to a "substantially different" roster. "It was only natural for me to call upon the artists I've worked with before," Mulrooney reflected. "They are people I know and support, and I’ve seen their art and careers grow."

Her voice carried a sense of gratitude as she showed me around the galleries, pointing out hidden details — minute brushstrokes, delicate chiseling. Their work spoke to her, taught her things, meant more to her than what was left on. "I feel so honored that so many of the artists have trusted me to move forward and keep presenting their work," she said. "A lot of good has come out of this. I'm taking a space from my past and making it my own. As I grow and differentiate myself from where I [previously] worked, it's important for me to build my own voice."

She laughed, adding, "It's a coming-of-age story, a little bit, which is kind of ridiculous – but here we are.”