Down the Rabbit Hole

“If these pictures and book can open up a new way of thinking and feeling for a viewer rather than telling them something they already know, that's a win and is beautiful.”

office sat down with Billet and Kline to hear from the photographers about the process, feelings, and ideas that brought this piece together.

How did Rabbit / Hare come about?

During the very confusing socio-political atmosphere that began to scream in the summer of 2016, the idea for the project started coming together right before the start of our final year in undergrad. We had this broad idea to go to Texas for its importance to our understanding or questioning of American masculinity that trickled down to us through our fathers and families’ relationship to Texas. The project took on the form of a two month road trip through the American south to Texas and back, because the road is what best facilitated our interest in embracing the unknown, interacting with people and looking at the country following the election of the 45th president.

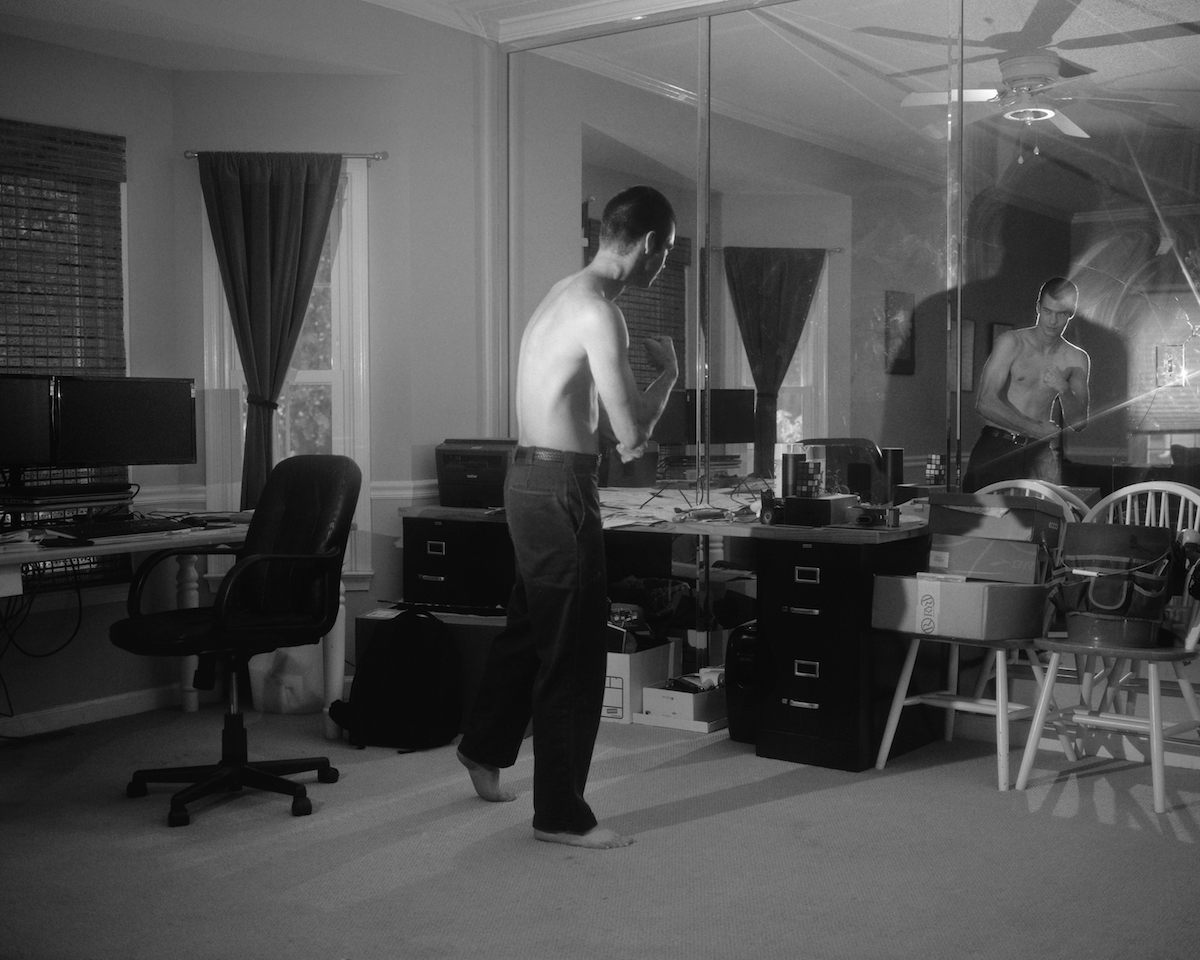

It had actually been largely fueled by where we grew up and who we grew up around. Both of our mothers’ sides of the family are from small farms in Spring Grove, PA, two of the men in our lives drove trucks, both our parents are seperated, and we lived a few blocks away from each other for the majority of our adolescence. Depending on who you talk to or what timeline of documents you look at, York was the first capital of the US or the fourth. Either way, you’d think this would somehow ground this place. But it never felt that way. It always felt like this place was constantly in between identities. The area we grew up in was largely middle class, blue collar with some shades of baby blue. The men in our family and in the general area held their visions and lives to a certain hard-edged, emotionally distant masculine stereotype, a stereotype neither of us felt at home in and butted heads with.

On I-83 going north out of York there is literally a 15 foot tall ripped man lifting weights spinning in circles at the York Barbell company. This identity made up the environment we were growing up in, so there was always a push and pull with our relationship to this heteronormative lifestyle that made up the majority. The way that Texas had been mythologized, romanticized, and dramatized for us through family and media, it seemed like the epitome of the identity we were questioning since we were in middle school, so we needed to go. We didn't have an option.

Did the state’s polarization play any role in the idea for the road trip?

There were political motivations going into thinking about the project before we hit the road. The nature of Texas being a largely red state, specifically in relationship to the resurrection of outdated “shoot first ask questions later” ignorant views that were coming back into the spotlight during the 2016 presidential election, was definitely important. But at the same time we weren’t going into this with the idea of illustrating these things we were already seeing in the media and things we already knew. Why make anything if you know what the outcome is going to be? The world needs to talk back with you.

However, as we mentioned before with our upbringings, Texas has always played a big part in our lives, even though neither of us had been there before receiving the grant. We used those elements and larger political motivations as jumping off points to get us on the road. But as soon as we got on the road it was important to keep our minds open and embrace the unknown chance encounters to form our new experience together, rather than let someone else tell us what’s what, and make images that can exist outside of a confined political discussion.

How does the contradiction of “gentle,” being in such a polarizing state, come about for you? Are these motifs you purposely set about creating?

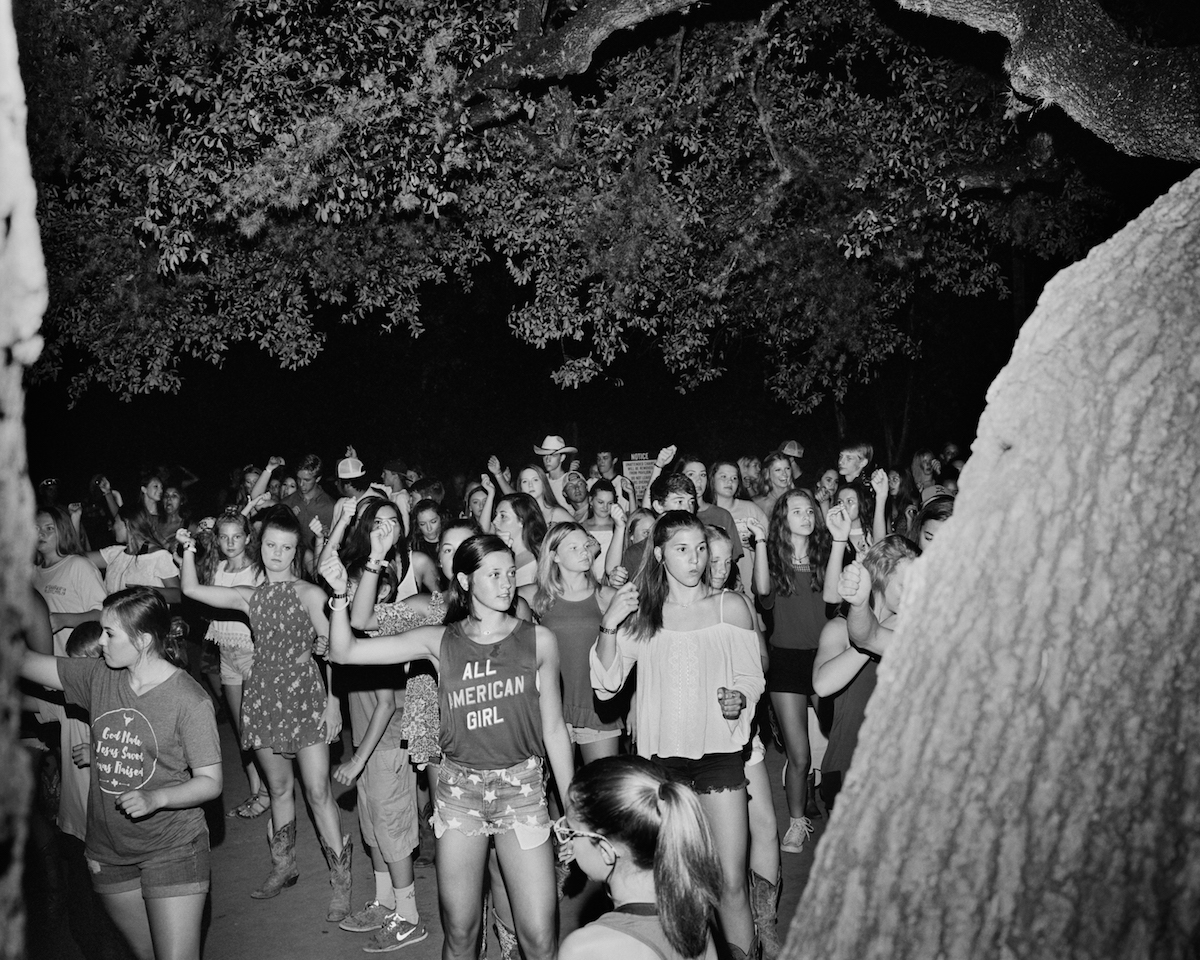

Billet: With everything we photographed, we had an open mind and heart towards it. We went into this space having no idea what to expect but trying to make our own sense of it. This contradiction came from us trying to escape from a place we called home, and expecting to be greeted with animosity. However, we were surprised to find the opposite: we found pieces of home along the way. We realized that the harder we pushed and tried to escape the place we knew, the more we found people and places that reminded us of where we come from. Since we shot on film we didn’t look at any of the images until the project was done and we developed it. We had no intention of this while making the work.

Kline: When we were getting ready to get on the road we had a few people and professors express explicit concern for the two of us. They knew how we worked and were concerned for our safety going into new places during a tense time in the country. We may have been a bit naive going into it but as soon as we got on the road and throughout the entire trip we really didn't run into any opposition. So right from the beginning, these expectations of tension made way for the openness.

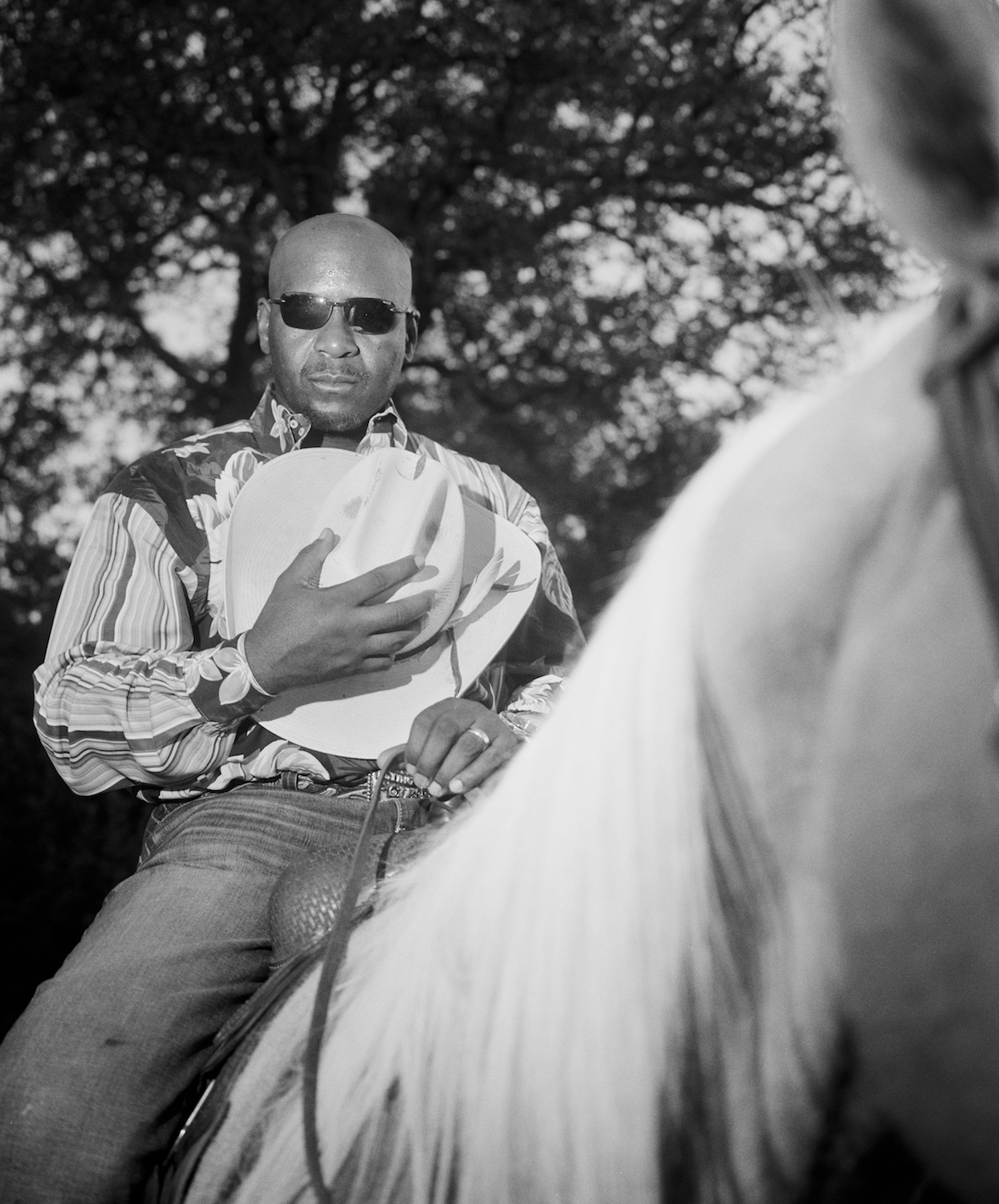

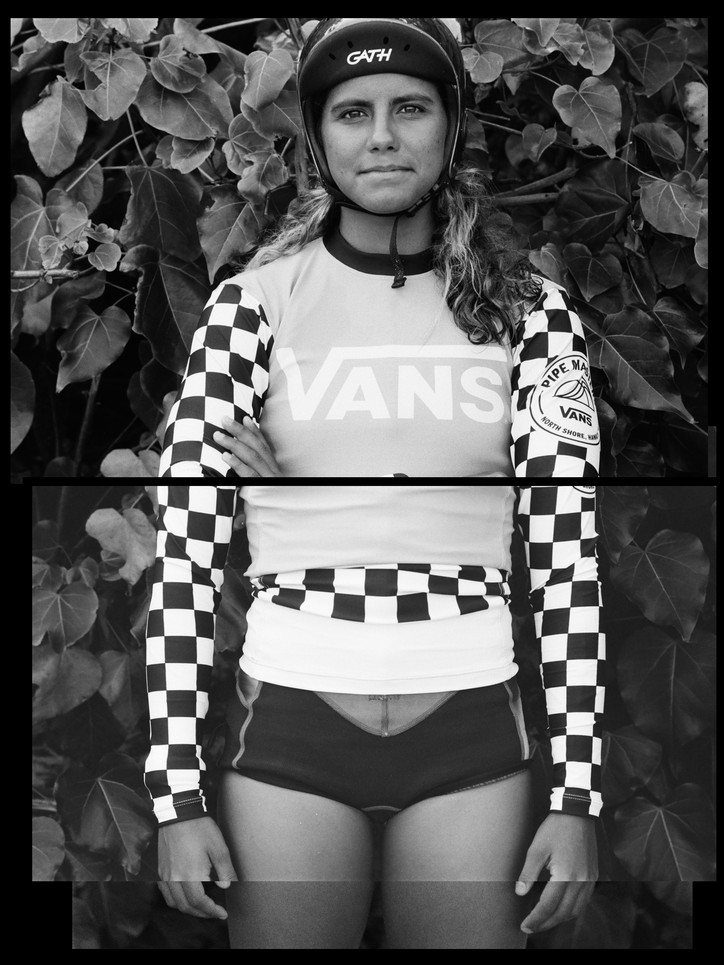

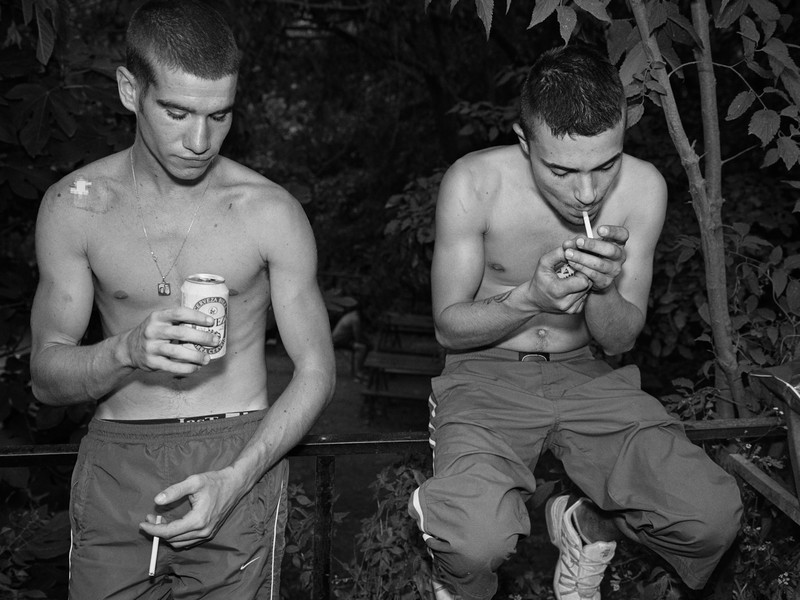

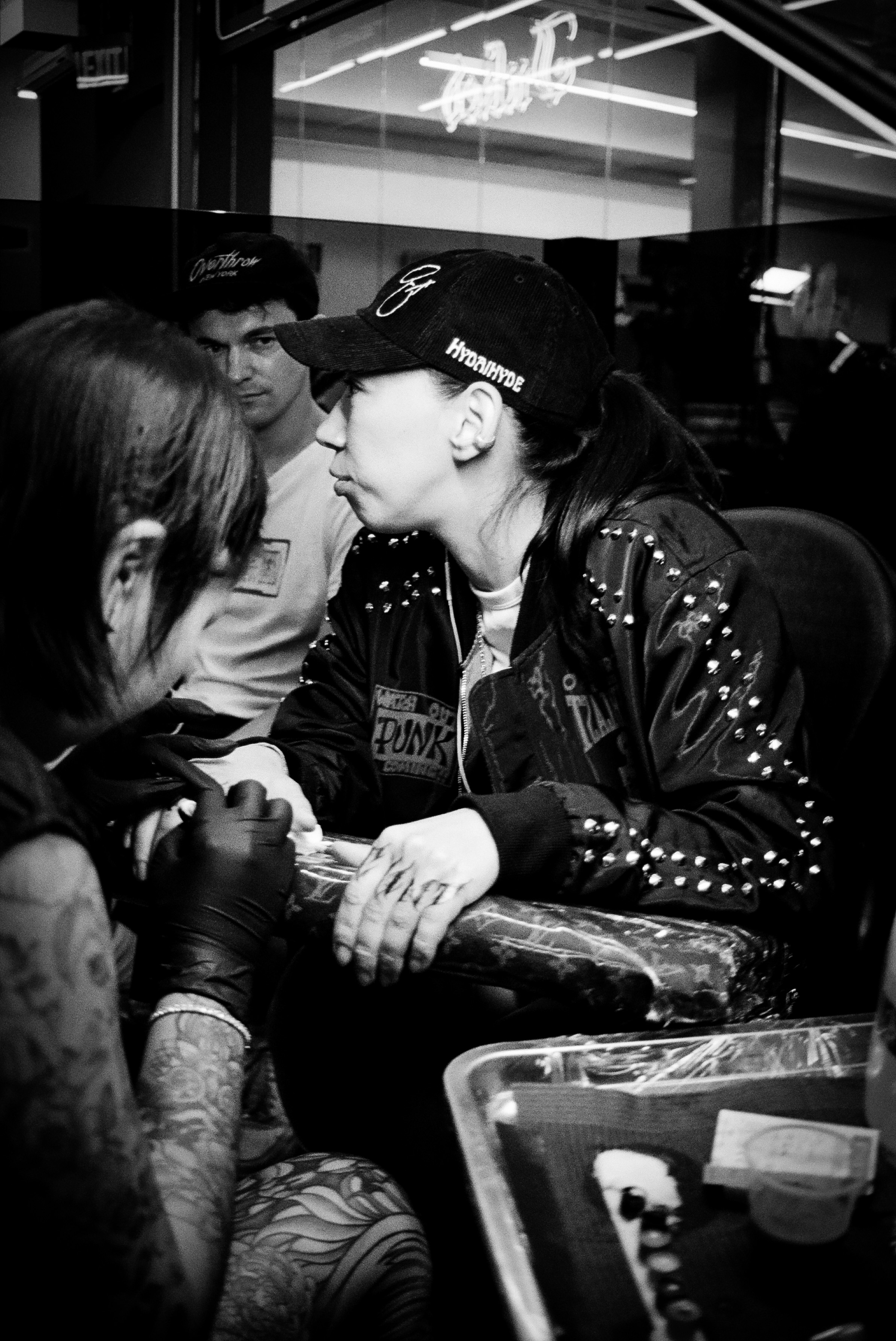

Photographically, I think it comes across most literally in the portraits of men. This might be obvious but many of the men we photographed just totally opened up in front of us, letting their guard down and sharing themselves, breaking down a bit. Which I do think was also pushed by the way we held ourselves and also the common trait shared between us of being male. If we wanted to work with people we had to open ourselves up as well and be vulnerable in the collaboration and spend the time in conversation to try and make a picture with them. Most of the people were just as interested in us as we were in them. As soon as we described what we were doing, that allowed for a way where we wouldn't just be just taking [photos].

We didn’t set out to illustrate these motifs of contradictions happening in a seemingly polarizing state, because we couldn’t. This was our first time being in any of these places so it was all new and we were learning on the road daily. One of the things that I think brought out the resulting gentleness was just how generous most people on the road were. Southern hospitality is totally a thing. But there was still a feeling of violence floating in the void just outside of the light that countered the openness, even if it wasn’t tangible.

What is it that attracts you to human vulnerability and producing art that provokes thought, possible discomfort, and possible pleasure?

Billet: Well, honestly I’m not a very good musician and I wish I could be. [laughs] But, in all seriousness, I think one of the most beautiful things about producing or making an image is that your emotions going into it can be seen. You have an opportunity to construct how this moment makes you feel, it’s not only what you’re seeing but a document of the atmosphere and thought of the place from my own viewpoint.

Going back to music, it creates a mood and evokes a whole array of feelings. Through my practice both in collaboration with Ian and on my own, I’m trying to do the same and allow for the viewer to enter my version of the world we’re living in. I think about the pictures, how all parts of it create meaning, and these parts of the image that we see are so familiar to us because they are an actual thing. The nuances of color, the space, and tones of an object that you can relate to, and they are not just an idea of an object. Everything around the object gives context to what is being shown. All of these aspects don't force you to try and automatically feel. With a photograph, you allow yourself to enter the space and work your own way around it. For me, a picture can be an individual experience guided by your private personal associations with the subject or object.

Kline: People are so interesting and weird and beautiful. Making work that provokes thought is so much better than just waiting around to die. To make something that makes me feel, that can make someone else feel is so goddamn special. We fuckin need people. If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around does it still make a sound? If I exist in the world but no one else is around do I still exist? I don’t think so.

Maybe that’s dramatic, but everything right now is dramatic. We need people and the variety of experiences that each and everyone of us brings to the table to open up the world and open up the stories. Even if opening the dialogue up brings in views we don’t agree with, that's what makes the stories more complex and interesting and human. Thank god everyone isn't a replica of each other in grey suits. It’s essential to produce art that provokes thought, possible discomfort, and possible pleasure because we need to, because that is what life is, it’s a spectrum of confusing emotions and our role is to embrace that and make something weird from it.

You can purchase Rabbit / Hare here.