The Edge

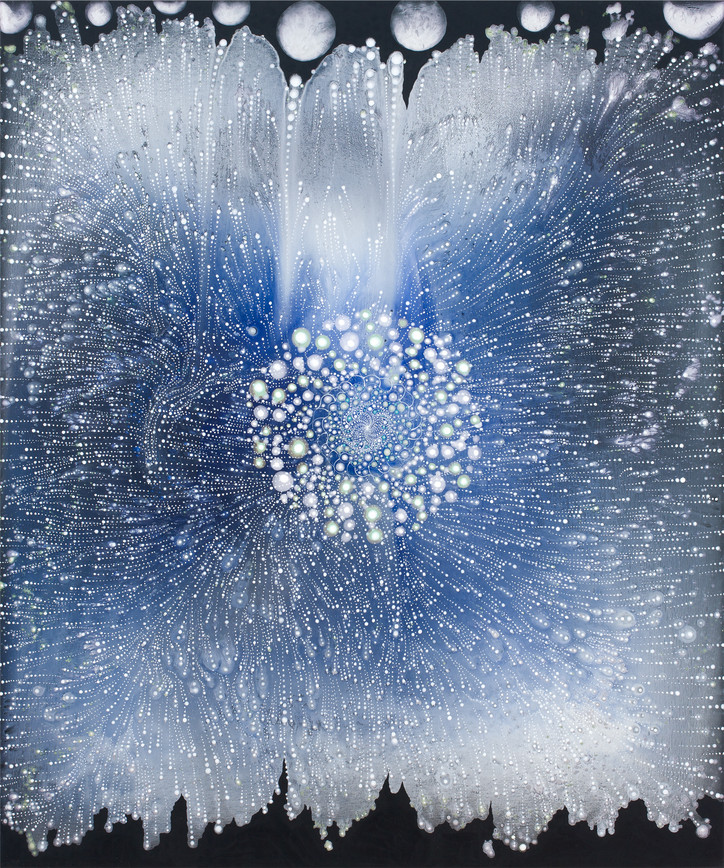

She told me that her work is often discussed in terms of mathematics, science, the microcosm and the macrocosm. Indeed, the paintings seem to exist in that odd space where the microscopic begins to resemble stars and planets. She seems startled at the comparison, since for her it’s all a matter of shapes, paint, and a balance of randomness with firm control — all to a bewitching result.

The artist has a friendly energy herself. We immediately connected over the fact that we're both from Nebraska. Her little dog barked from his kennel as I arrived, his dog toys forming a sculptural pile in the corner. Over a tray of cookies, we talked about the illusions in her canvases, potential energy and black holes.

Tell me about your work.

The idea for the show that was a little bit different from what I’ve been doing, is that I’ve been looking at a lot of Asian-influenced images. So, I got intrigued by the use of black silhouettes, and it might be elaborate hairstyles in these Japanese prints, or clothing, or robes—these wonderful images of warlords with great silhouetted, stiff kimono shapes; Indian paintings where there’s elephants in the water and you can only see the backs of them, and every now and then, you can see a trunk. So, even though they’re pictorial, they became these abstract shapes—things that looked like they were holes, negative space holes in the image, or they were positive shapes, the thing they were depicting. I love that flip between the positive and negative.

It’s like they’re both simultaneously positive and negative—like, you can never tell if they’re receding or advancing.

So, for instance, this one ['Cloud River'], which is based on a very stylized Japanese river shape, and it’s been cropped, so ordinarily the river would wind around, and normally this would be cloud shaped, and this would be land or water, but then it flips, and the black shape is the thing on this green background, which is what I’m really interested in—this ambiguity. For instance, I start out with these very random pours of paint, and the paint moves around and it dries into shapes and surfaces, and then I come in the next day and that’s the great surprise of it—I get to see what happened and I spend a lot of time looking at it. And then I try to overlay some kind of control or repeated, sort of labor-intensive thing over this randomness. So it’s those two things: the obsessive control element, and then a loose randomness.

Like a controlled chaos. Kind of like Dada, where they allow randomness.

I love Dada, and I think there’s some of that. Now, I’m not a fan of surrealism, but I also think it tips over into those surrealist parlor games, where they would do things like exquisite corpses, are you familiar with those? It’s a game they would play, where one person is assigned the head, one person is assigned the torso, and you fold it so you only got to see a quarter or half inch of the drawing and then they all connect.

Oh! We’ve played that at office, actually.

They had all kinds of crazy games. Like games to create these weird poems, in a similar way, where you’re adding words onto someone else’s words but they don’t hear yours. But all of those games had that kind of embrace of the random and unexpected. So, there is that surrealist influence, but then there’s a lot of control issues that I have, too.

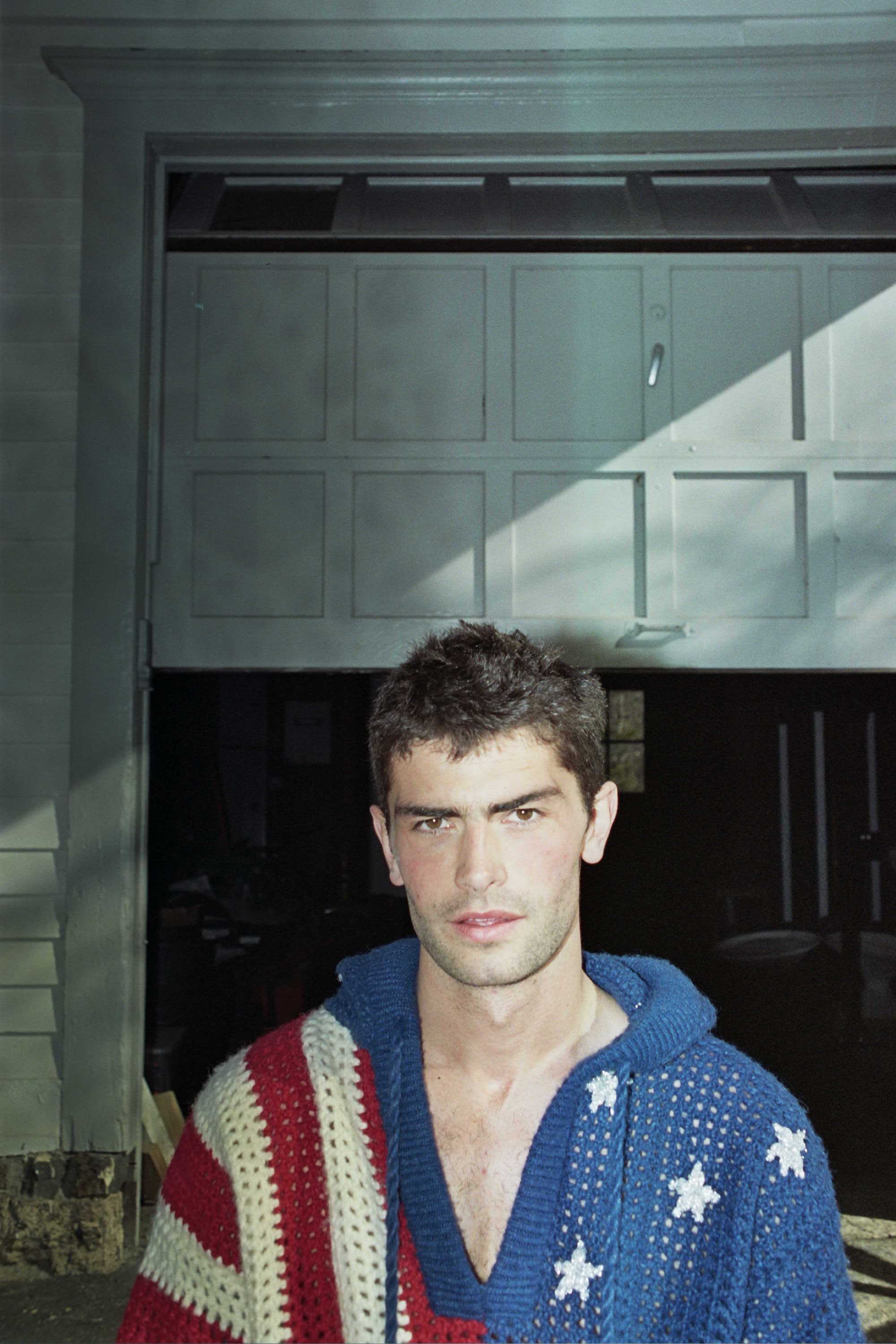

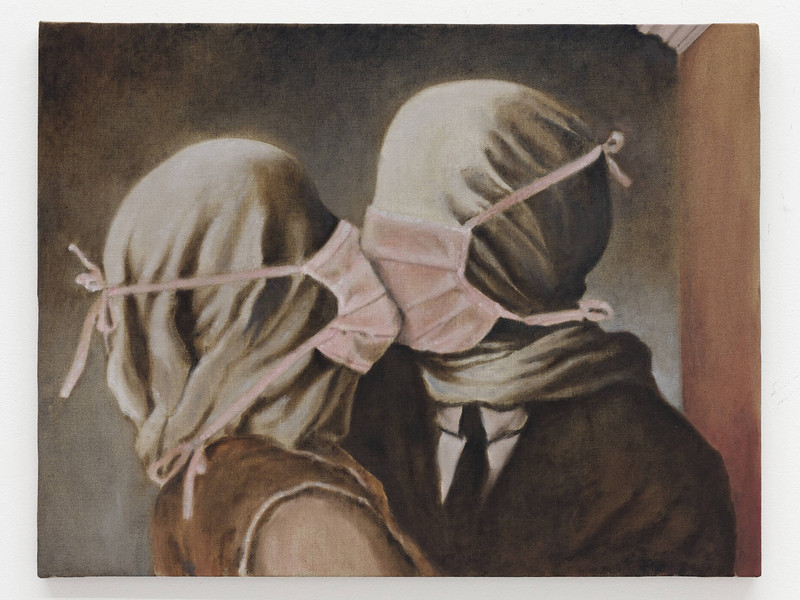

Above: 'R Edo,' and 'Hello.'

It almost reminds me of stars or constellations.

Yeah, particularly in my older work, was really seen in that kind of cosmic, explosive, Big Bang sort of way. There were a lot of images that were exploding or imploding.

Do you feel like you’re like you’re playing with the scientific?

People have written about it in terms of the scientific and the dichotomy. There’s this science and math thing combined with the other side of that, but I can’t think of a good dichotomy for you.

The art side of it.

Yeah, I’ve been saying random a lot, but chance, the intuitive, uncontrollable aspect. But, to your question, I’ve been asked by people who know math if I use a system—like if I have a very set way of going about it, and I don’t. So, there’s not any hard math in any of it. And the only reason I think people think that is because I used to start with the smallest brush and make the smallest little circle in the center, and then gradually the circles would get bigger, and I would go out in a spiral or in just a straight pattern, and as everything moved, it just started mimicking natural growth patterns, which then goes back to the math issue, or fractals, or things like that.

Earlier, we were talking about Nebraska. Do you ever feel like that comes into play in your work?

Yes, and it’s been unexpected. It’s lovely, but strange, that it would come back to haunt the work.

How so?

Not so much in this show, but in earlier shows, I was trying to figure out how to change the work, and at one point I just dropped in a dividing line, just a flat, horizontal line. And of course, the minute you do that, it’s a landscape. So, the fact that it was this completely straight line, you have sky and earth, or land, it’s like a tabletop. You’re from Nebraska, you know what it’s like, especially since we’re not even from where there are rolling hills, it was really flat. So, they actually became these weird Nebraska landscapes, and I think when you live there the highway is this big thing, being on the road, so you have this road that recedes into the vanishing point on the horizon, and then you have this big sky. So, suddenly everything took on this landscape illusion. I didn’t really intend it but at some point I was like, 'Okay, I’m going for it.' I actually named a couple pieces ‘Nebraska.’

I have this one piece, 'Lift'—you’ll appreciate it since you’re Nebraskan. With this one, I’m not working from anything—they’re all imagined, but when I was a kid my dad used to try to take me to go see the sandhill cranes. I never saw any. We would go out and sit in front of the cornfield for twenty or thirty minutes and nothing would happen. So, my dad would say, “Okay, I guess there are no sandhill cranes today,” and I never saw them. I mean, I’ve seen pictures of them, but this became this stylized version of them. I knew people who went to Kearney and said they were magnificent. How could I have lived there for 18 years and never see them?

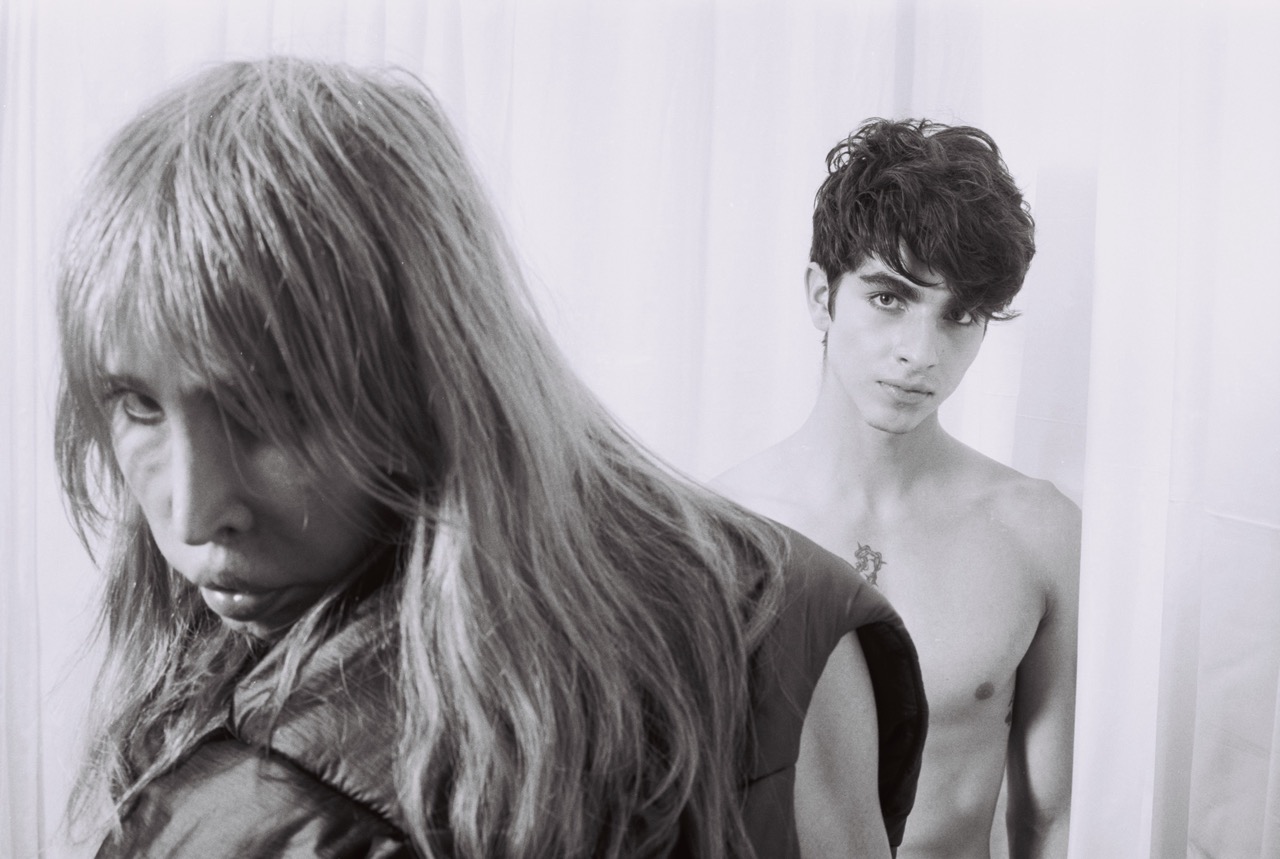

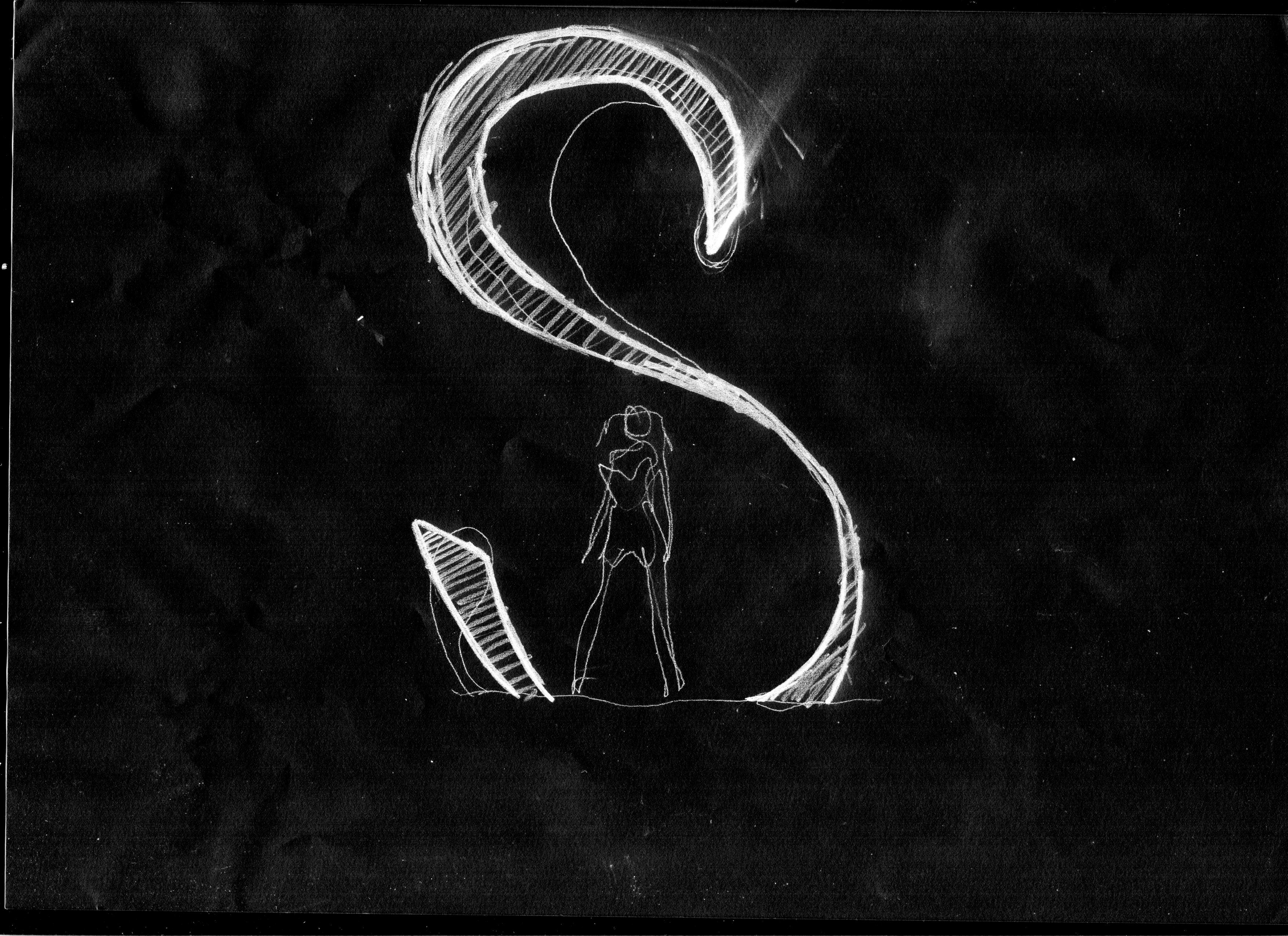

Above: 'Shadow Love,' and 'Too.'

I was kind of disappointed because I always just sort of assumed they’d make the state quarter a sandhill crane.

Yes!

And then they made it Chimney Rock, which, I’m not even sure what that is.

I’m not sure where that is either, yeah.

How long have you been in New York?

I’ve been here since 1985. So, I’m sure I’ve been here before you were even born.

And you’ve been doing art that entire time?

Yes. I love New York. I mean, I was intimidated by it—I was afraid of getting lost and all that, but I fell in love with New York right away, and thought, 'Oh my god, I’m home.'

Do you have anything to add about the show?

It just opened, and it’s up till October 6. What else can I tell you about the show? Oh, this painting, [Manifold], if you get a chance when you go by, it’s five panels and it’s actually about 18 feet by about 6 feet, and again it’s this sort of weirdly stylized shape—a silhouette of a river shape, and there are all these little geyser, fountain, candle things that somebody thought were little Bodhi Satvas. But I’m interested in that space between where an image is almost something, it’s directed but it’s not specifically nameable. For instance, I love this painting, and it's—I don’t know what it is. Is it an island or a big fish or a blob or a ship? I’m not sure what it’s doing—is it suspended in this air? Is it indented into the background? So, that’s what I’ve really been interested in lately.

Like a sense of uncertainty.

Yes, and I think that uncertainty means possibility. I actually love the way you said uncertainty, because I think there’s a little bit of ominousness about it, especially when you’re using a lot of black and silver or white. So, there’s a like, creepiness or ominousness, and then there’s the other side, which is possibility, choice—like I’m the viewer I get to see what I want to see.

Almost like a black hole—it could destroy you or it could lead you to another world.

Yes—but you're very optimistic, because most people would say, 'Get me away from the black hole.' I think that’s revealing of our personalities, because most people would be like, 'No, don’t let me go in there.'

'Outset' will be on view at DC Moore Gallery through October 6th, 2018.

Photos courtesy of DC Moore Gallery.