Even Better Than The Real Thing: Poets Respond to the Whitney Biennial

Abstraction in Reverse

By Kyle Carrero Lopez

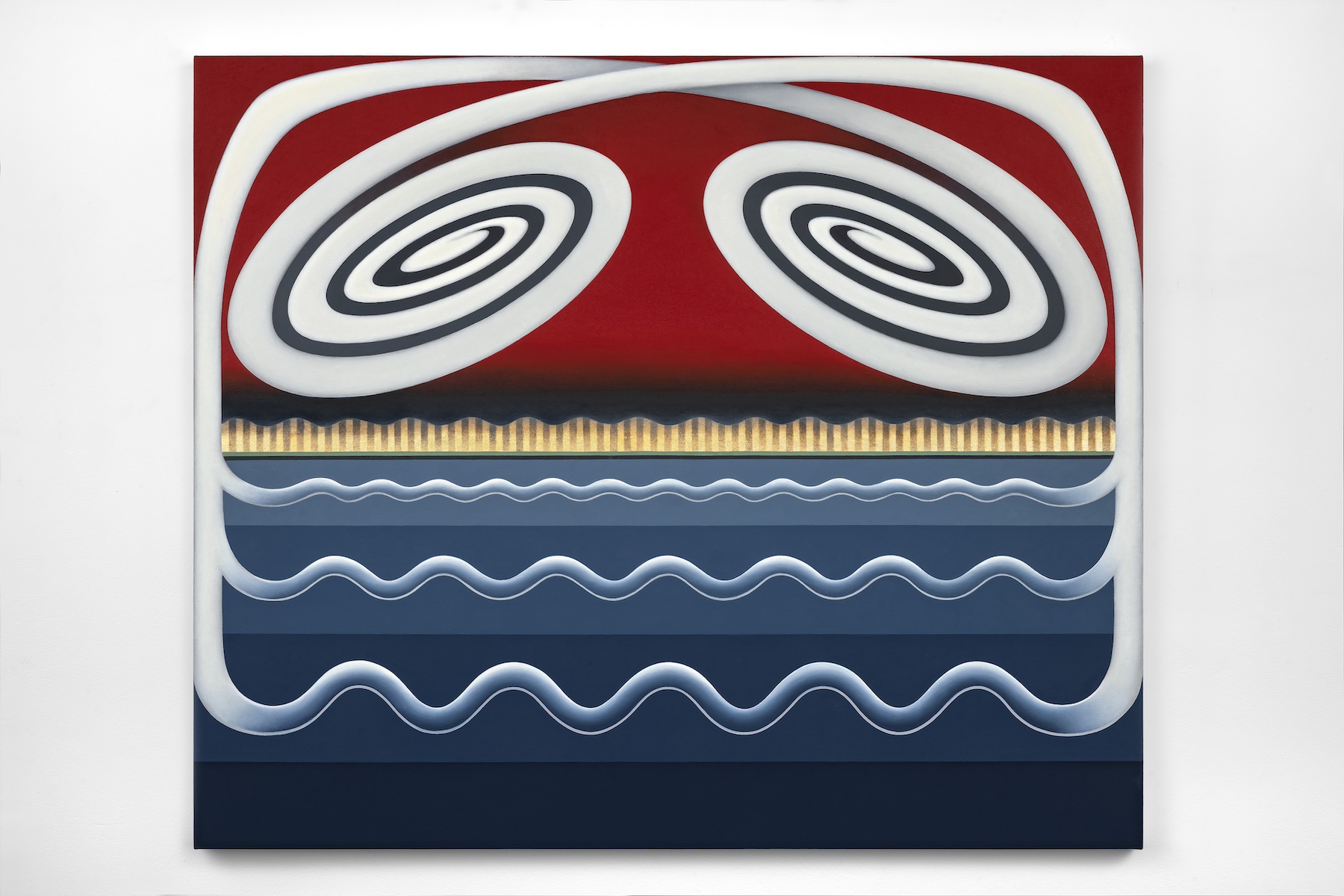

after Takako Yamaguchi

The laptop logo looks like a cartoon apple

and the cartoon apple (in two parts) looks like a sideways

sort of jagged tooth below a pointed oval — its floating stem:

not simply oval but vesica piscis, fish bladder, the shape made

between two intersecting circles, heart of the venn diagram,

the heart itself in the center of one’s chest,

though leaning slightly left—an imperfect center—

the heart itself symbolized by a shape unlike the heart;

the false heart representing true feeling, true love,

its shape, in one telling, pulled from Aristotle’s theory of its shape:

three chambers with a dent in the middle,

and though we now know it’s four, the false heart isn’t so far off,

essence of the true shape there in the abstraction,

the true heart loosely similar,

the true heart on a lab desk pre-transplant

pump pumping the false heart’s trademark red,

blood-soaked comice-pinecone-misc. THING,

vigorous, and thick, and horrifying,

ours

“He Is Here!”

By Kay Gabriel

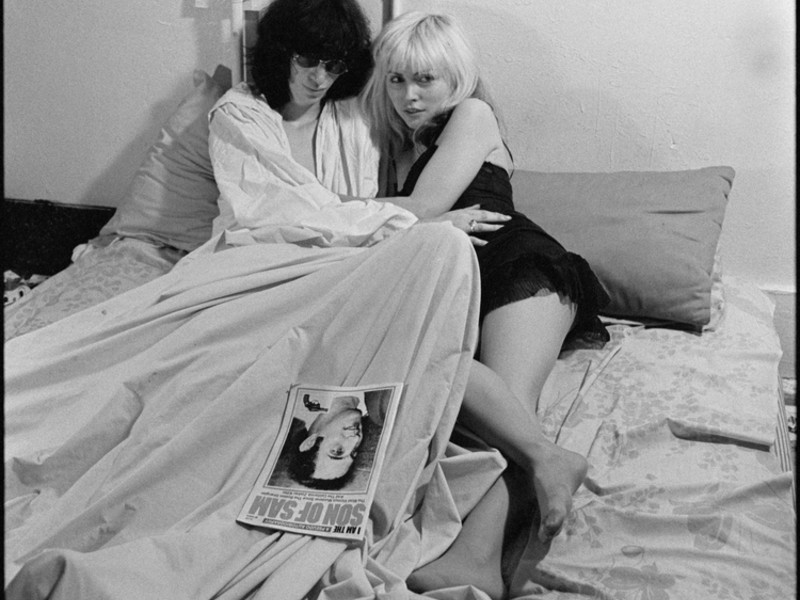

See: Sharon Hayes, “Ricerche: four,” 2024; ektor garcia, “teotihuacan,” 2018; Tourmaline, “Pollinator,” 2022.

Sharon Hayes seems patient.

She asks a lot of older people what they think is going on,

If the gains they fought for have endured,

where they feel safe and if they

think the world is better now or worse than when they were young.

These questions can be frustrating. I mean, I get frustrated,

sometimes, asking people if they think it’s a bad world

and why, and what to do.

Hayes’s interviewees agree the world is worse,

even, than the one in which they came of age, though

they don’t agree on why. They feel something disintegrate.

I’m paraphrasing—they didn’t say disintegrate.

A man acknowledges legal rights.

He’s Black, gay, looks to be in his late 70s.

Watching the moral panic grow—

paraphrasing again—

he suggests the win is fragile. Where’s safe?

Home. Where’s home? A retirement

community in Tennessee. We used to be so afraid

of a liberal world, that it would subtract the force

of our critique, like shock absorbers on a car, or a

Katamari ball yes-and-ing its path across a surface

pounded flat. We, I mean, queers whose consciousness was

easy-baked in like 2012. We regarded with

suspicion the capacity of art to—what, exactly?

Challenge? Sure, if you put it

like that. I mean we watched people sharpen

critique while the relatively powerful repeated it, and metrics

like average inequality, average deaths per day

tunneled deeper into nightmare.

I’m trying to explain a feeling—dispiritedness;

the sense that pricking conscience

wouldn’t do much, even in highly trafficked environments.

Were we wrong? Hannah Baer called herself a “skeptic

at church,” about poetry, not art, but it feels similar:

suspicion about the relationship of content to changing

unbearable conditions. And not even poetry per se but poetry

readings, which can, sure, be dreary affairs. There’s your

ex on his phone. There’s a bad feeling. There’s a pile

of interesting people. Or it’s transcendent,

I mean, the words change something—clarify the obscure, offer

strength to the downtrodden, make productively

light of misery. Cecilia did, “sucking

and sucking,” wishing Chiqui would fall

on stage. Pamela Sneed remembered

Assotto Saint defiant at a funeral: “He is here!”

and I wept. It’s like: “Cecilia!” Patrick wept, when Nan Goldin

read Cookie Mueller’s “Last Letter” in the new Walking Through

Clear Water— “I know, I know, I know that somewhere

there is paradise … Courage, bread and roses,”

see, Hannah, I’m crying right now,

so I don’t hold your position.

Peter Weiss in Aesthetics of Resistance has

his antifascist fighters, exiting Spain,

study Guernica in the woods, and Amilcar

Cabral wrote poetry while he fought the Portuguese.

He died before the victory he made possible.

I could go on, even if the “art world”—a euphemism

for the class that holds the keys—shreds its revanchist wave.

I believe that that, too, will pass,

not just like that. I mean I think that people change their ideas about reality

faster than reality can change. I suspect they do it

faster even when together, which is why Hannah’s

right, it’s church. We’re moved to see each other

moved. It’s nice that the Whitney likes trans

women artists so much: Ser, Pippa, Tourmaline.

Tourmaline’s “Pollinator” video is stunning, her orchid

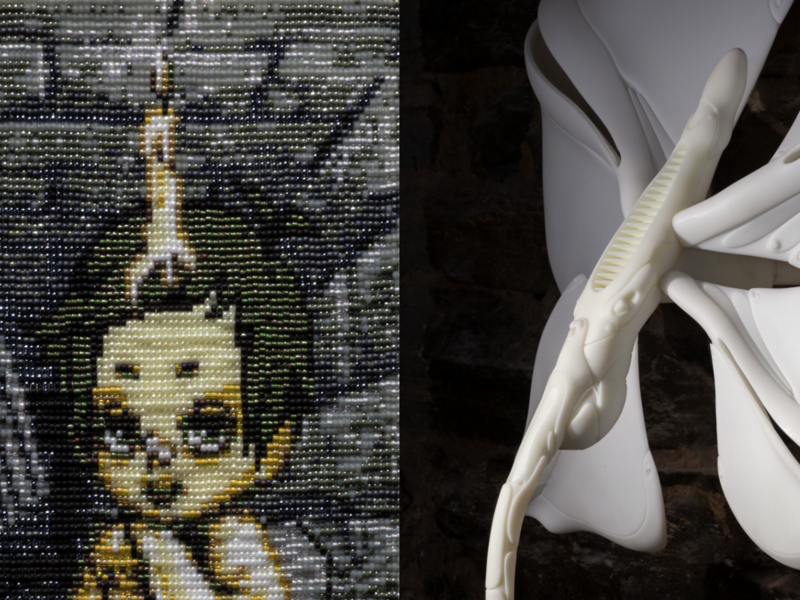

headdress, her Marsha research. So are ektor garcia’s

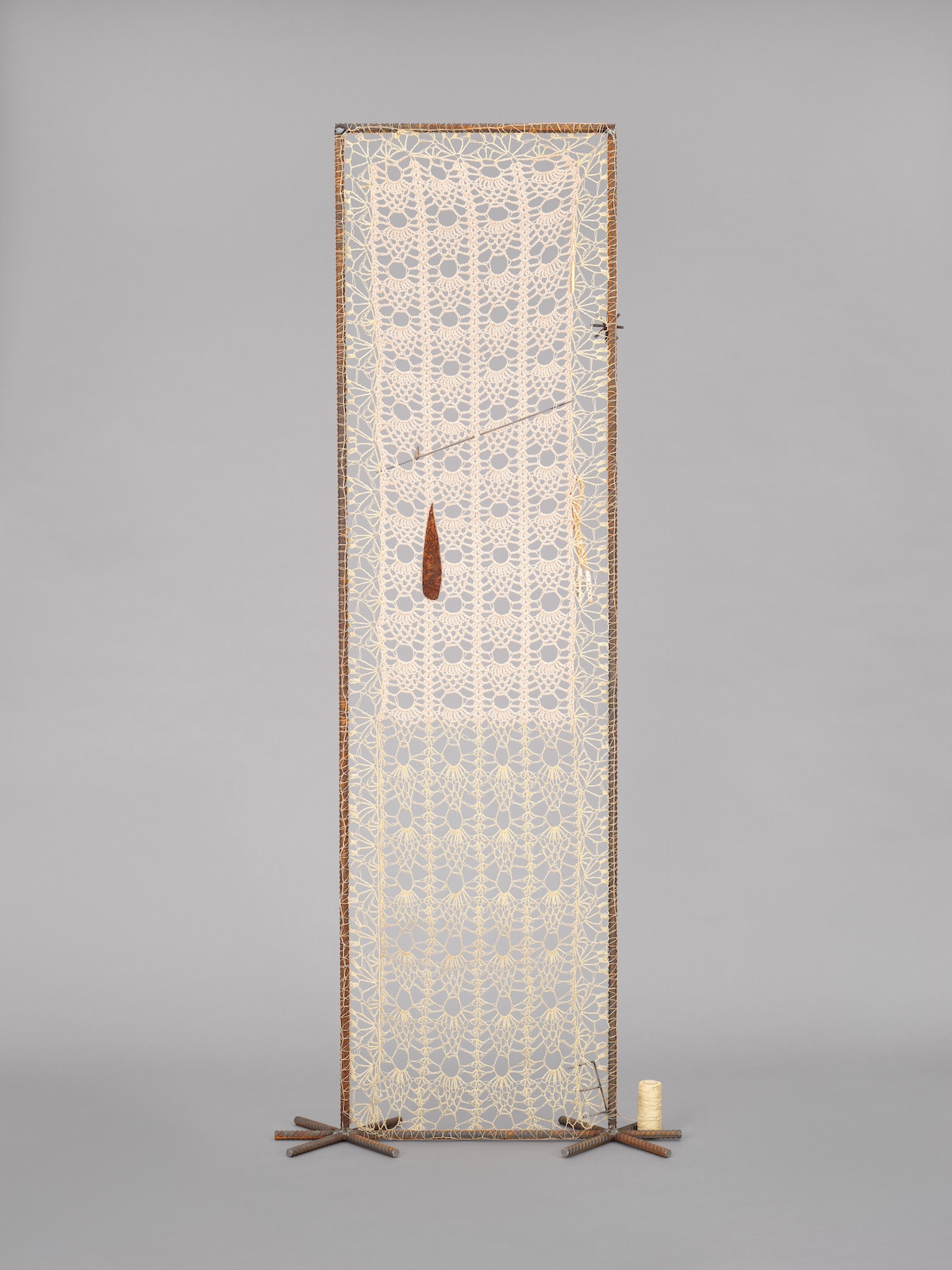

sculptures. “Teotihuacan,” named after the ancient

Mesoamerican city in the Valley of Mexico, joins mesmerizing

white crochet to a steel frame. I think about the artifacts Diego

Rivera collected there and framed in the vitrines

at Anahuacalli. Then you climb the stairs and see his planned

mural, Stalin and Mao offering peace to the peoples

of the world—Pesadilla de guerra, sueño de paz.

No, really! Stalin holds a dove. A generically ugly Uncle Sam fumes. His eyeline,

Stalin’s, extends across the mural to where Frida Kahlo

engages visitors. Probably you don’t agree. You wouldn’t say that that’s

how it went. Maybe nor would Sharon Hayes, or her crowd

of gentle older queers. Someone should ask them.

Dejygea

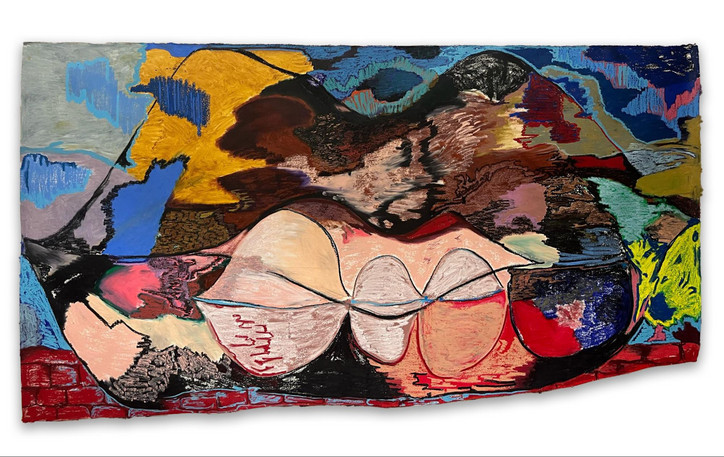

By Kyle Carrero Lopez

after Mavis Pusey

I looked and looked and still know not what it means.

Dejygea – Pangea, caesura, déjà voulez-vous.

Would love to know what Miss Mavis meant with that title,

yet I know that not to know for sure

is itself a gift. Reaction vid or GIF:

Kandi Burress cocks her head and cracks

you just made that up! to Porsha Williams.

And did!

Oil on canvas. There’s black and white,

and reds, greens, blues: the three primary colors in physics

(sorry to yellow)

and here we see physics sing out, the oil scene

informed by architecture informed always by physics,

structure and scaffolds and quake safety, heat and energy, and and and and!

It’s Miss Mavis’s take on the Lárge Apple’s

constant construction, constant noise,

the way its buildings shoot up and plunge down.

It’s Miss Mavis back at the Biennial after the ‘71 Biennial on Black artists

with no Black curators,

a promise undelivered, promise given a new look

by fresh eyes 53 years later:

Blackstraction redeemed!

Sitting in the crowd of a Black poet’s reading,

Hanif Abdurraqib overhears a white woman ask her neighbor

how can Black people write about flowers

at a time like this?

If I’m Black and I make a thing up and it fails to convey

the right Black thing to the right donor’s taste, did the tree make a sound?

Friends from college may remember a time, a period really,

when I fell afflicted, obsessed with saying Lazy Susan, laissez-faire.

It came forth like revelation and I couldn’t stop speaking it aloud,

or sending texts with cryptic lineation:

lazy susan

laissez-faire

Deep within my jokey, specific, idiosyncratic dome

I looked and looked and still know not what it means.