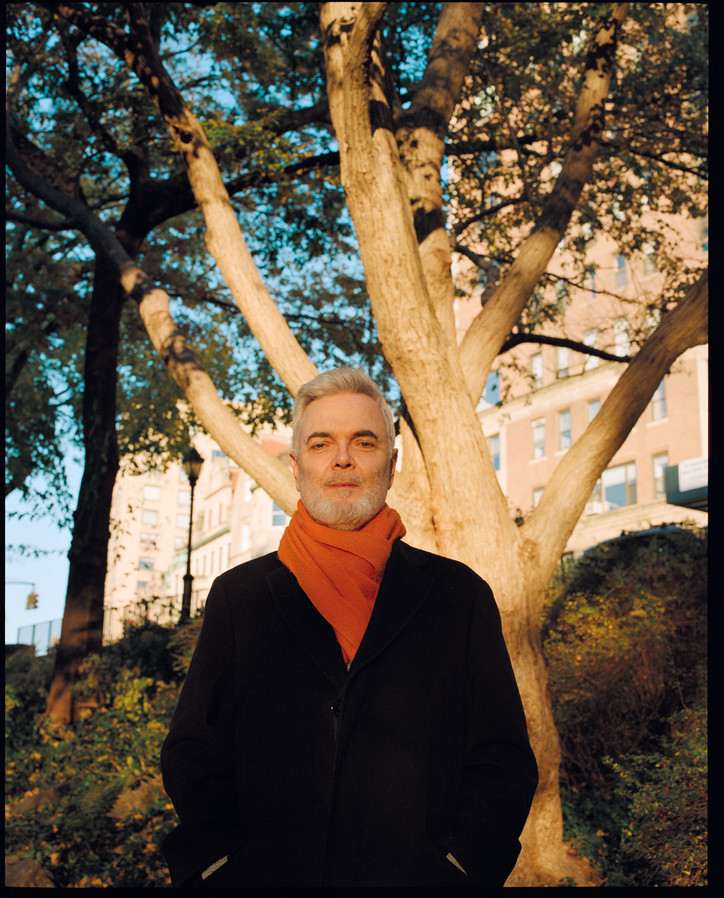

Mel Odom: Doll Parts

Having landed illustrative gigs with everyone from the New York Times Magazine to Rolling Stone and Playboy, Odom has distinguished himself as a leading commercial artist, thanks to his Art Deco-style figures wrought with energy and homoerotic tension. His works have appeared on book covers, including for a number of novels by Australian author and Nobel Prize winner, Patrick White. In 1991, however, Mel switched gears, channeling his passion for creation into the making of a Gene Marshall doll. A 1940s-era film noir ingenue, Gene was voted by collectors as the most important doll since Barbie.

Although it’s no surprise Odom has enjoyed success in every creative venture he’s embarked on since his arrival in New York in the 1970s. It’s the refreshing clarity he possesses, both in his art and IRL, that he describes as something that has less to do with knowing than with the understanding that not all things are meant to be known. As part of the city’s gay community, Odom survived the AIDS epidemic of the ‘80s and ‘90s, and it’s this very experience, among others, that has caused his energy to blossom into something so much larger—and visually striking.

What’s that book that you’re holding?

It’s a book about the illustrator Aubrey Beardsley. They say now that he foretold abstract art—that he was decades ahead of what was the norm in the art world at the time, which is only now being appreciated, really. So, I feel pretty snug about it—especially after having a crush on him since I was fifteen.

That’s how I feel about Goya!

Isn’t it great, though? Isn’t it the best thing when there’s somebody whose art really speaks to you like that? I had some really nice kid tell me that when they’d seen my work, that I inspired them to go into art. That’s one of the best things to hear—that something you did triggers that creativity in someone else.

I agree. I also that observing a work of art is such a singular experience—one that can never be recreated or replicated. And when you see a painting that really resonates with you, the experience is so personal.

It’s the most personal thing you can do in public, actually. I don’t think that I’ve ever seen an original drawing by Beardsley—I’ve seen reproductions of them, of course—and I suspect that when I do, eventually, it’s going to be even more intense. When you see prints of things, and then when you see the real thing, you just realize all that was missing from the prints—all of the subtle colors and lines that you didn’t see before. It’s a very singular experience—I don’t think that two people ever share exactly the same feelings about an art work.

My Latin teacher once told me a proverb I will never forget: ‘The pen is mightier than the sword.’ In your case, it’s the paintbrush, but what do you think?

Well, I can fall back on a trite truism that a picture is worth a thousand words—what we were just discussing about Goya. When you see something that connects with you on a deeply personal level, you may not have expected it to when you walked into that room. You may have just been a tourist there, and suddenly you see something that’s a piece of you being reflected in a painting or a sculpture, and I’ve been amazed with my own work and how much people provide their own context, and what it’s about—and that’s great! I’ve been asked many times, ‘Well what does that mean?’ It means whatever it makes you feel—whatever you come up with. I don’t like telling people what my work means because that limits it—that limits it to my interpretation of it, whereas if you just show it to them and let them feel however, it’s wide open, and it might be much more than what you originally saw there.

Getting back to Aubrey Beardsley, though—he actually worked in pen, so in a way, that’s the perfect analogy for him. Or someone like Georgia O’Keefe—I love her paintings, and feel so moved by her color and what she chooses to focus on. So, I think, if you’re lucky, the pen is mightier than the sword. I love reading, but when you seen something, it’s just different—like chapters and chapters, rather than just a sentence. And when I’m working on something, I try to put things in there that are questions, so that people have to provide their own answers—their own context as to what’s going on.

Are you saying you use visual symbols as a way of bringing certain questions to the forefront?

Yeah, exactly. When I was working as an illustrator, I did a lot of book covers, and I loved doing them, but I would try to put something in the drawing that made a person pick up the book to find out what it was about—like, ‘Huh? What does that mean?’ You’re more than likely to connect with something that creates a question in your mind than if it’s something that’s completely explained. I like putting mysteries in my drawings and paintings, because then people have to think about them a little bit more to figure things out. I think really wonderful art brings up those questions in your mind, and you get lost in your own way of answering them. That’s why it’s such a release to go to a museum and see things that are just sublime. There’s a statue of Jesus at the Met here and it’s very unique—I’ve never seen another one like it. We’ve all seen a million different depictions of him, but this was the one that made me stop and really look and think—and I love that. He’s my favorite Jesus, and I grew up in a Baptist family, so there were Jesus [depictions] everywhere.

Actually, one of my favorite drawings I’ve ever done is one that’s called “Al Parker Jesus.” I was doing it for my dad when he was alive. I did this drawing, and I looked through photos to try and find a model. I finally found the perfect face, and he was a pornstar—as it turns out, a very successful one. I drew half of it, and then my father died unexpectedly. So, I never got to give it to him. I ended up putting it away for a long time, because I felt this regret that I hadn’t done it in time to give it him, because I think he would have loved it. But then, when I found it again, I named it “Al Parker Jesus,” and it was accidentally kind of perfect, because it went from the profane to the sacred in that one image. Al Parker also happened to have died from AIDS, so it had a lot of context, for me, that I didn’t even intend when I found the photo. I think a lot of the most important content in art is accidental—it just reflects something different than you thought of initially, and becomes something else.

Good art—at least, for me—meets you halfway. It supplies the beginning, and you take away what you want; then you leave, but still end up thinking about it. Or, you see a piece of art that you know nothing about it, then after doing a little research and revisiting the work, the whole meaning shifts. It’s such a beautiful process.

It is. And you know what else is fun about it? It becomes a part of who you were at the time you saw it. So, it becomes very much about you, too—about what you could bring to it then—and when you look back on it later—like the drawing of “Al Parker Jesus”—suddenly it’s got a lot more going on, because of how you’ve changed. Art can be a wonderful barometer of you—if you let yourself respond to it. It’s how much you can give it in that single moment.

It’s like hearing a song and it transports you back to such a specific moment in time.

There’s a song by Denise Williams called “Silly” that brings me right back to my first boyfriend in New York. I have it on my computer, and every once in a while, I’ll play it. He died, unfortunately, and sometimes I can’t even handle listening to it. But that’s what art can do for you—it gives you things and shows what you have to give. It’s great. Art has never disappointed me as a career.

When I was looking at some of your pieces—even your Gene Marshall doll—all of your subjects appear to have variations of the same face. Who’s your muse?

I watched a lot of old movies when I was a kid—Gene is a movie star from the ‘40s and ‘50s, and she reflects that era’s idea of beauty. But I also grew up loving the Pre-Raphaelites [paintings], and there’s that in her, too. When I’m drawing, there’s always a face I go to that’s just what, over the years, I’ve come to think of as beautiful. One of the cool things about getting older is that my idea of beauty has broadened—I mean, I see people now that I wouldn’t have thought of as beautiful before. This city is filled with unbelievably beautiful people—it’s almost enough reason to live in New York. You walk down the street and you see these men and women, and it’s just like, ‘My god, how to they get up looking that gorgeous everyday?’ A lot of them don’t even know it—a lot of them probably have been told they aren’t beautiful.

So, my ideal of beauty has evolved over the years—it’s widened—but Gene was kind of a storybook version of a beautiful young movie star, and I intentionally wanted to make her look a little unreal in her innocence. I wrote a book about her too, and I liked to think that she was the best version of myself—the best of us. She was brave, and kind, and she comes from a lovely family. In the story, her brother dies when she’s young, so she’s experienced grief at an early age, and has empathy because of that experience. Empathy for other people is such an important thing, especially these days, where we seem to suffer from a lack of it a lot of the time.

Just looking at your work, it seems that you developed a very strong aesthetic identity almost right off the bat. What’s one of your most vivid childhood memories that continues to inform—or greatly contributed to the development of—this identity?

Well, I drew from the time I was about four, and I lived in a little-bitty tobacco town in North Carolina. There was like, four-thousand people in the whole town, so there weren’t any art galleries, and there certainly was not a museum nearby for miles and miles. I looked at cartoons—Disney’s Silly Symphonies were these beautifully illustrated and animated stories filled with mermaids, and pirates, and fairies. When I would see those, I would be on fire—I would be like, ‘Oh my god, this is what I know is out there, but I just don’t have access to it.’ I very much lived in a fantasy world as a child—much more than my parents ever realized. I really believed everything that I saw. When I was five, I remember my mother, who by the way, saved and dated my drawings.

All of them?

Yeah, all of them—not dated all of them, but saved all of them and gave them to me in a dress box one day when I was grown up. When I looked at them, I could remember everything that I was thinking when I was drawing them—it was like being given a diary, and it really was the best gift anyone could have ever given me. But when I was young, I would just draw all the time. Then, after my parents went to bed, I would get up and watch old movies on TV. But I didn’t think that they were old, or that they were from another time—I thought there really was someplace else that looked like that, where I didn’t live, but desperately wished I did. So, movies and cartoons were really my way of seeing what I thought was beautiful for the very first time.

In what ways do you think the art has world changed, or stayed the same, since you started working in it?

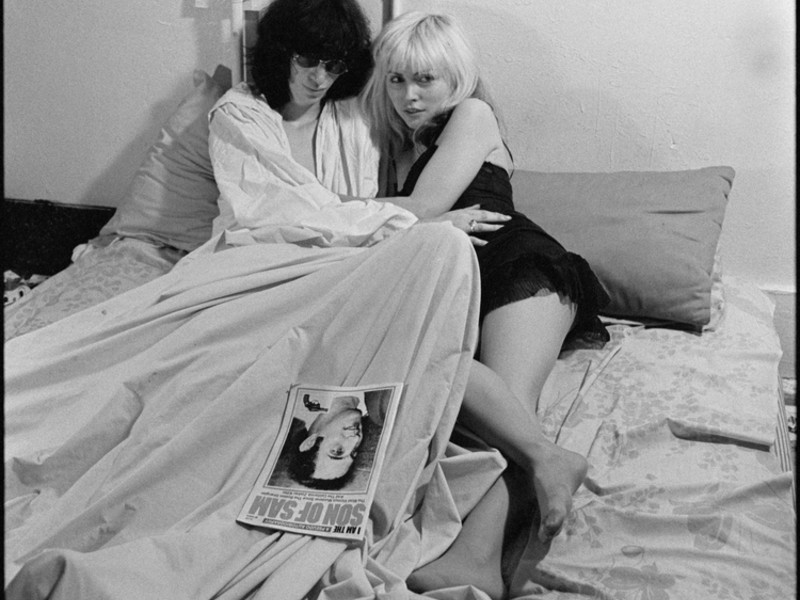

It’s not an easy answer, because your game plan is only yours, never anybody else’s. So, you have to figure out what you want to do—what you need out of it. I moved to New York in ‘75, and I was very, very lucky, because I started getting work right away. I was very dedicated—I was crazy focused on my work—and by the early ‘80s, AIDS started happening. It was so frightening—literally two-thirds of my friends died—so I focused on my work as something I could control, because I couldn’t control anything else that was happening around me. People were dropping like flies, and my work became my grasp on any sense of security. I guess this is true about anything, but particularly in art, it’s not just what you bring to it—it’s what else is going on in the time you bring it. I had never considered that in my early thirties, suddenly I was going to be saying goodbye to my boyfriend and my closest friends, and when that happened, I knew I had to find something within myself that gave me some sense of stability.

Early on, especially, people would go so fast—people would get sick and die within months. But I never did. I was really just like, ‘Huh?’ I actually couldn’t understand, like, ‘How come I’m still well?’ I mean, I’m still asking myself that question this many years later, though now I do know the official answer: it turns out I have an HIV-resistant gene, the CCR5-delta 32 Mutation. I had two boyfriends die of AIDS, and when I was tested, I was HIV negative. I was convinced my doctor was lying to me. In fact, I told him ‘You’re just lying to me because you think I can’t take it!’ It was the only time I’ve ever cried in a doctor’s office.

So, do you believe in fate? Or chance? Or both?

I believe that they are the same thing, I think. I mean, I don’t know. When this happened, I was just so relieved, and astonished—have you ever heard the term ‘gobsmacked?’ That’s exactly what I was—gobsmacked. I didn’t even understand how I could be that lucky. And that’s how I thought of it at the time—lucky. But also, when I moved to New York, I remember feeling just so at home -- like I belonged here. So, I feel like I’ve felt little bits of my fate in advance, so much so, that it gave me the drive to fulfill that. You know? I didn’t sit back waiting for things to come to me—I was very diligent in my work, and still am. So, I think it’s both of those things, and I don’t think we’ll ever know what is divine providence and what’s just luck, and I don’t really want to. I like good mystery, I really do, and I hate when people feel like they have to explain everything—I think that kind of diminishes it, because it’s just what they think it is. I’d rather say, ‘I don’t have a clue’—I’d rather accept that it will forever be a mystery and go with that. And when it’s something as profound as how I’m still alive right now, I wouldn’t want it explained.

I’d like to think that there’s something out there, some combination of things, akin to magic. None of my drawings ever would have been successful if I hadn’t done them in the first place, so you do have to own it a little bit yourself—you have to be willing to acknowledge your place, your role, in it, as well. I hate when people sit back and wait for things to happen to them. I’d rather work at something and see what happens because I worked at it. Especially in a career like art. The art world has always been difficult, and you have to decide what you want out of a career in this world. I never expected to be rich—it would be nice, of course—but I turned down some things that might have made me more money, because they were just not for me. It’s like what actors say, ‘If there’s anything else you can do, do it, because it’s a tough life’—if there’s anything else you can do other than an art career, do it, because it’s going to be easier, and you’ll pay your bills more regularly. But I was never good at anything else—drawing is the one thing I’ve always been good at.

But art is like romance—it’s scary. Sometimes, when I’m starting something and just looking at the white canvas in front of me, I think, ‘Is this where it all runs out?’ You have to understand yourself, and know what you are capable of. Deciding to be an artist really wasn’t a snap decision—it was who I was from the start, and I just hoped that I would be lucky enough for it to work.

Buy Mel Odom’s work here.