Slash

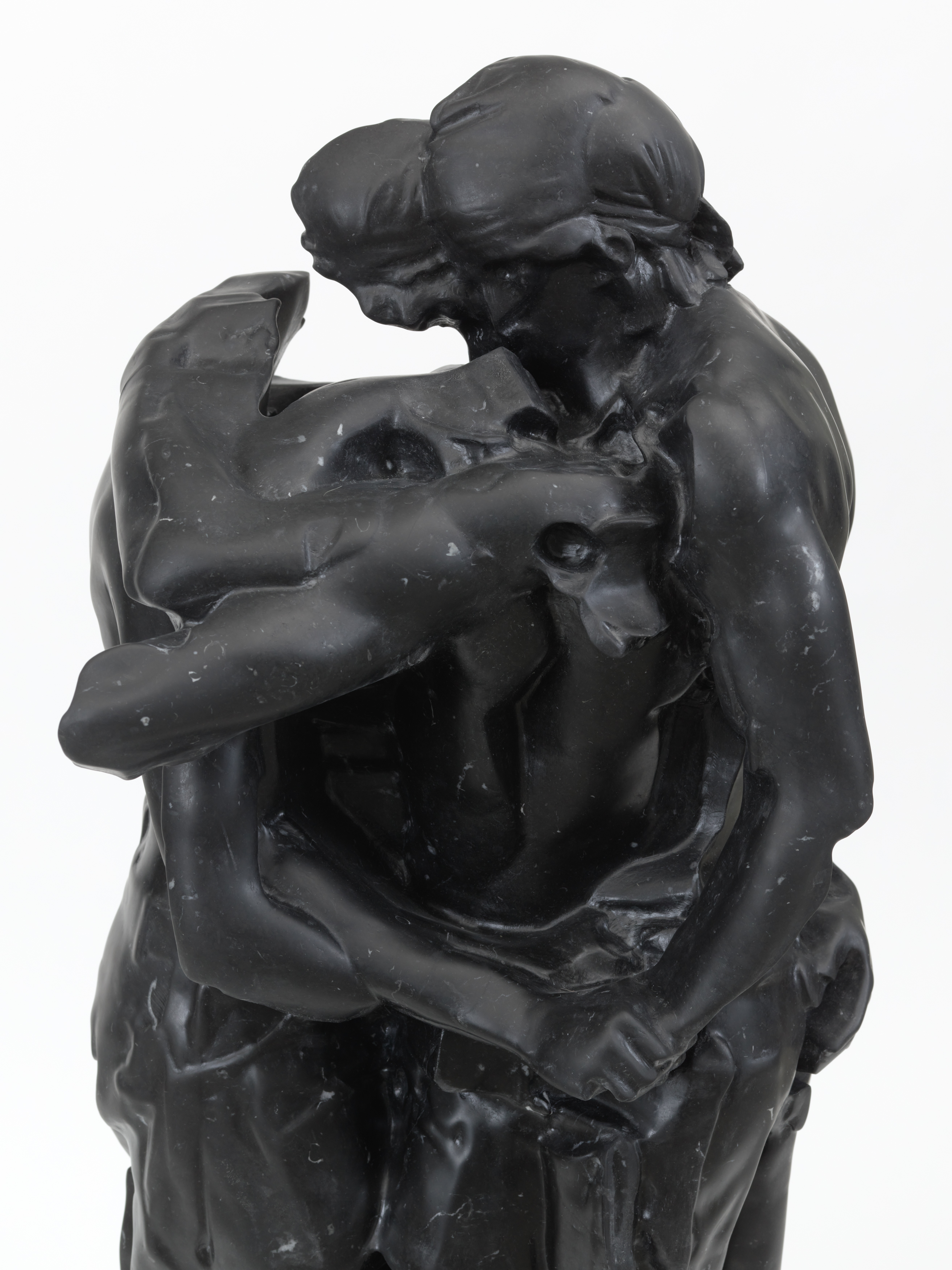

Homoerotic tension is the binding theme—be it between beloved fictional characters, iconic historical figures, or intellectual heavyweights, most scenes build toward the two characters acting on the sexual urge bubbling between them, but transition to the next scene just before the would-be moment of realized romantic connection. The binding homoerotic thread returned to again and again is Captain Kirk and Spock, of which there is an extensive romantic literature authored almost entirely by women—if the factual-seeming moments of the play are to be trusted.

It is a cool and accessible take on the weird and intense current cultural focus on all things gay, all things trans, an essayistic revelation of the underlying sexual tensions that have always existed between friendly characters of the same sex. At one point you feel a thesis developing, one that feverishly contemplates the fraught question of what our culture collectively desires, and the many fractured versions that this entails.

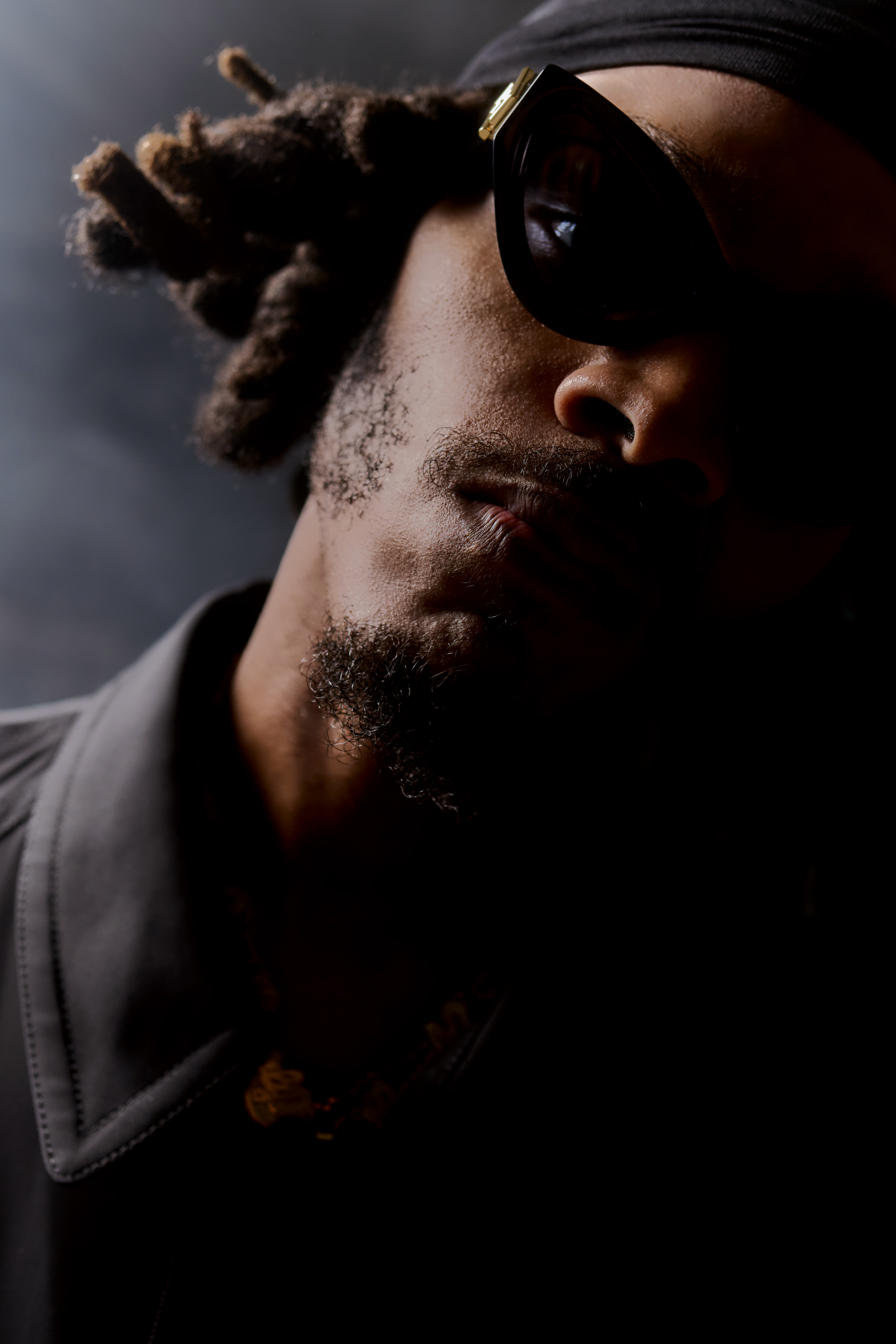

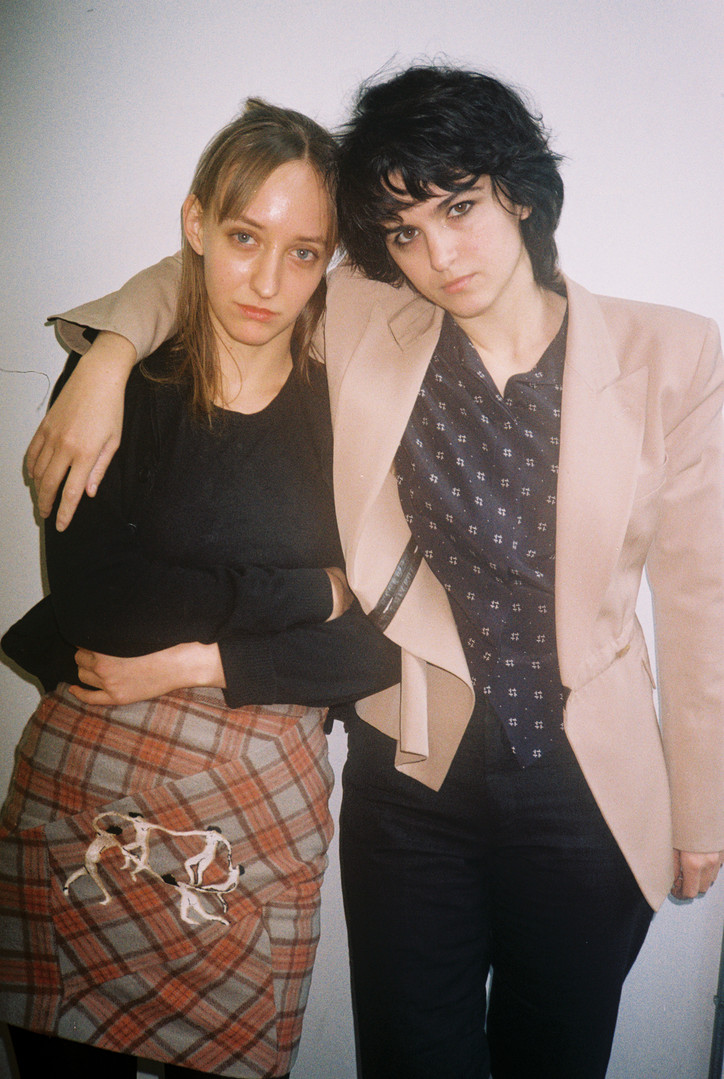

After a recent performance, Hennessey and Allan stopped by office to talk all things Slash and fan fiction.

What draws you to theater and playwriting?

Leah Victoria Hennessy: We’re both recovering theater addicts and this play would constitute a major slip in our recovery. I swore that I wouldn’t do any more theater after I wrote a play and directed it a few years ago. Emily was the star—it was so stressful, it made me realize that doing theater without institutional help is just too hard. It felt like it took years off my life and I promised that I would never do that again. But somehow, we got sucked back in.

How?

Leah Victoria Hennessey: We have a web series called Zhe Zhe—it’s the name of a band in the show, but it’s also a cutesy gender neutral pronoun. So, we had the show, but we would be asked to do live performances connected with the show, not theater, but performance art. So, we started doing those performances just the two of us, ahe first one we did was the first version of Slash.

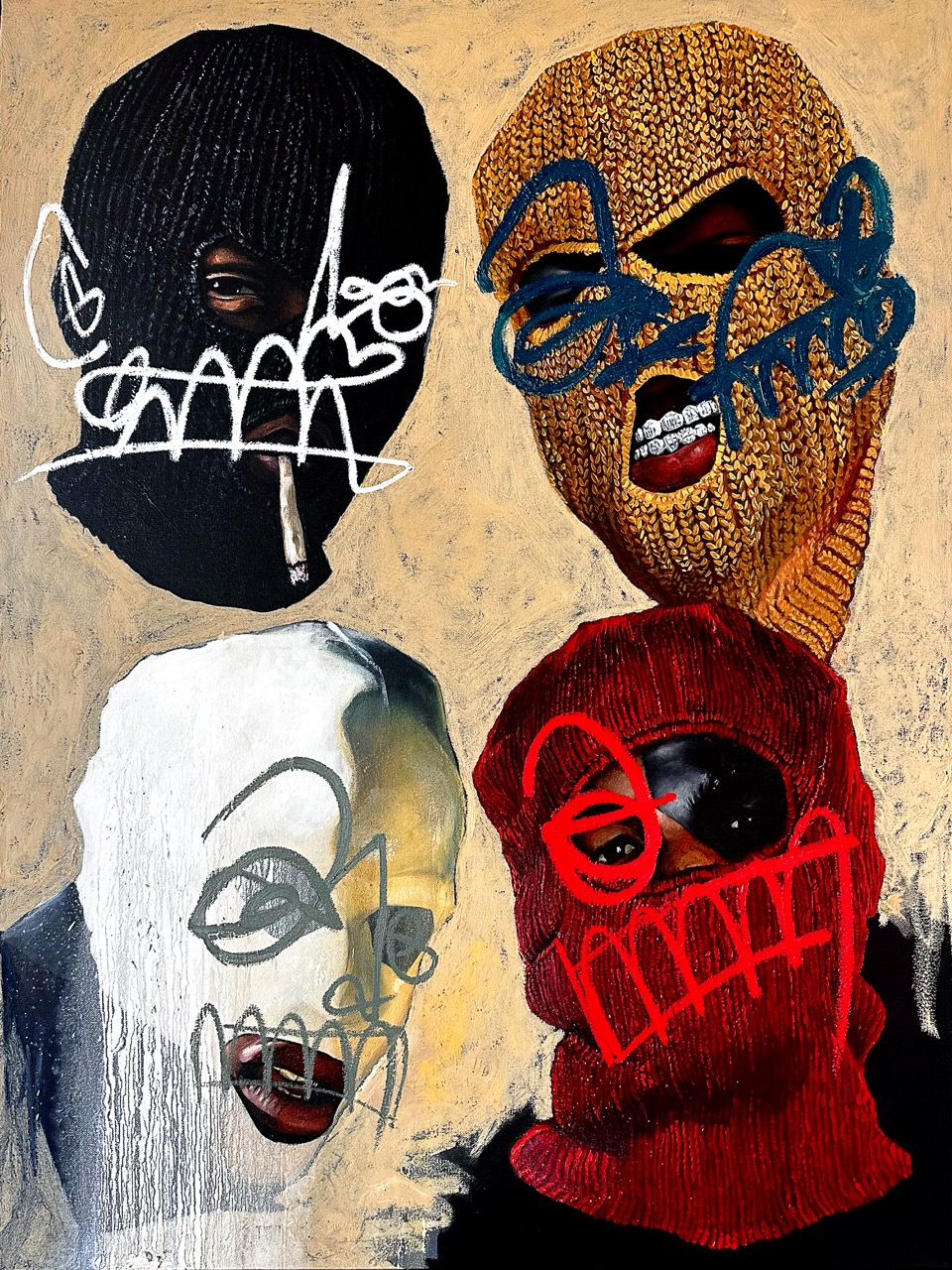

What was the idea behind Slash?

Leah Victoria Hennessey: We thought of it as cosplay. We wanted to take something that wasn’t usually considered theater, like a cosplay performance, and do it in a theatrical setting. That was the idea. Originally it was performance art, and it was much more ironic. Then we had a monthly show in the West Village, and that’s where we developed most of Slash, but I still wasn’t thinking of it as theater.

How did you get into theater, Emily?

Emily Allan: My first piece of theater that I directed and conceptualized was when I transferred elementary schools and I would take a bus across town and pass by Jefferson Market Library, which I learned had been a women’s prison. I had a group of five friends that I would take the bus with and we developed this piece of site-specific theater. There was one bus driver who was into it and he would announce it for us.

When did you two start working together?

Leah Victoria Hennessey: For a long time, I was disillusioned with acting, then a teacher introduced me to new method—one based on impulses. It was anti-Stanislavski, anti-the method. It healed me and reawakened my passion for performance and got me writing plays. After school, the friends I had who were in his class and I started our own writers and actors workshop to develop new work. Emily came into that, which is ultimately how we developed Zhe Zhe. We’ve just been working together for so long, it kind of feels like you don’t just find your soulmate, you make them. We Frankenstein each other into our collaborative ideal. It wasn’t that chance encounter—it grew slowly. A lot of the stuff we’re passionate about we got into together.

What’s your collaborative ideal?

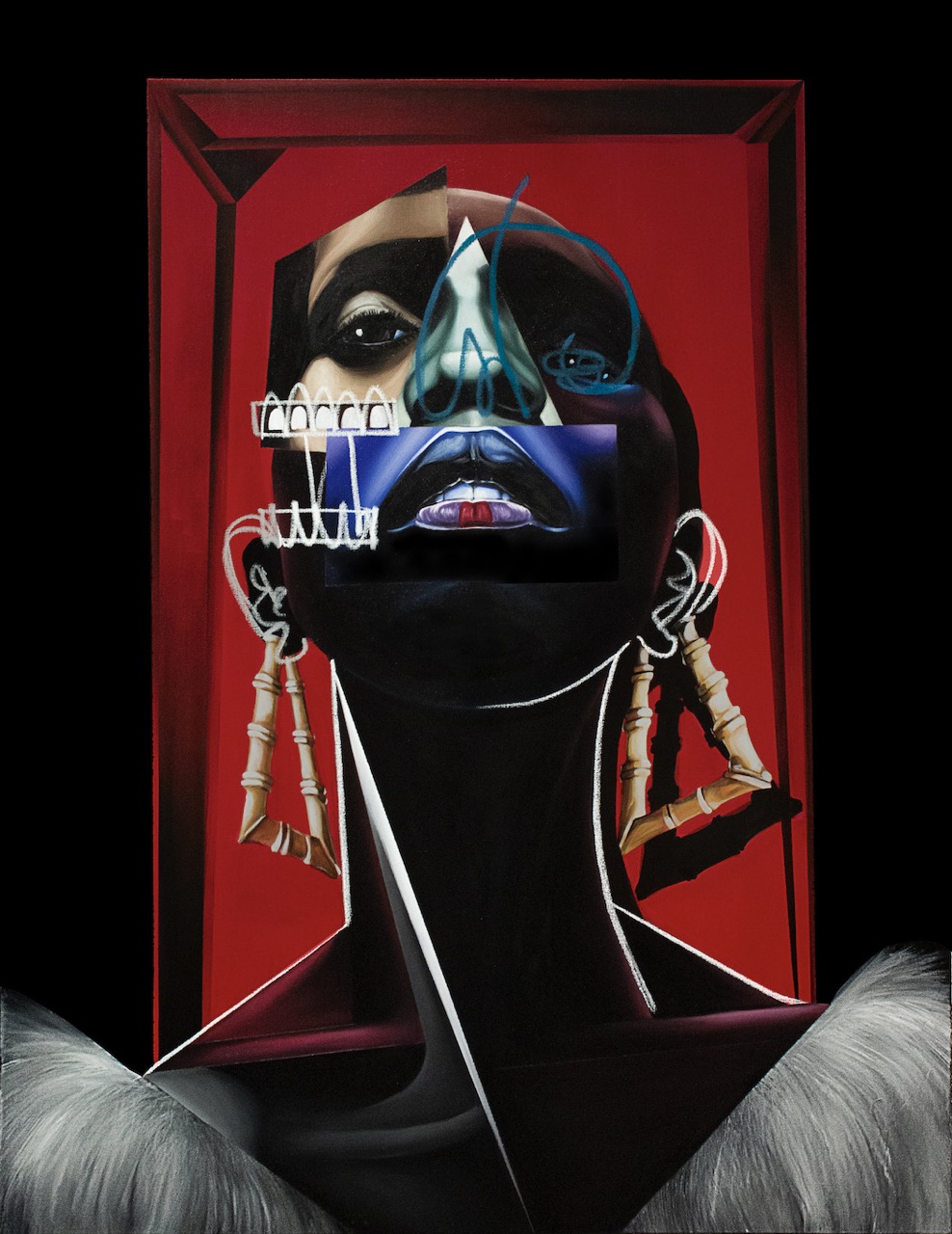

Leah Victoria Hennessey: We want to be funny in a subversive way that questions normalcy. I think a lot of comedy right now is upholding the status quo—it’s losing its bite. I don’t think of us as comedians at all, but it’s important for us to be funny in a way that challenges people’s preconceived notions. Also, we want to explore the way experiences are conditioned by the media that we consume. There’s no pure experience of reality. So, we don’t have any interest in purifying ourselves of cultural influence—we’re much more interested in affirming the collaged reality.

Emily Allan: In a way that’s sincere.

How would you describe Slash to someone who hasn’t seen it?

Emily Allan: Slash is the name of our play, but it’s also a genre of fan fiction. The play is a deep dive into the world of homoerotic fan fiction on the internet. If there’s a narrative, it’s that there is a blonde and a brunette and they feel trapped in their world. They have a feeling that nothing is real, and if it is, how can it be? They feel that there must be something else. So, it’s their attempt to escape or test the limits of reality through roleplay and ritual. They go through a series of ritualistic cosplays of two usually male archetypal pairs, living out this prolonged romance.

Leah Victoria Hennessey: I’m interested in games, ritual and fantasy. Slash is very much a game that we play and it gets very confusing who the real characters are, and who are the characters that the characters are playing. The original or authentic is left open-ended—it’s open ended if there is any escape through games at all. This kind of roleplaying is the kind of thing that if I could still do with my friends—we wouldn’t have to do it in a play. Emily and I can obsess together, but I wouldn’t be able to say to Emily, let’s ‘pretend’ I’m him.

Do you remember, when every sentence started with that word? I remember when I was young, I was in my room playing and realized that adults don’t do that. So, I promised myself I would never stop imagining and pretending.

Emily Allan: That’s what the play is about.

Is fan fiction mostly written by women?

Leah Victoria Hennessey: Most slash fiction, which is homoerotic pairings of possibly straight characters, is almost entirely written by women.

Did I see a critique of that somewhere in the play? You guys were addressing that women write homoerotic relationships because traditional hetero relationships aren’t depicted as dynamic.

Leah Victoria Hennessey: It’s not a critique, it’s a take. In the play, we incorporate big chunks of this piece by Joanna Russ, called "Pornography by Women for Women with Love," and she posits that women fantasize about homoerotic male relationships because men are allowed the complexity and depth and equality that, when she was writing this in the ‘70s, she didn’t feel like women had. Kirk and Spock’s relationship, for instance, was portrayed as more equal, more fulfilling and more noble, and that love between man and a woman can never escape the context of life and patriarchy.

So, it’s a desire to see noble love without limits?

Leah Victoria Hennessey: Without those power dynamics.

Emily Allan: It’s about projecting a fantasy onto something that’s more equal in power. Some people pointed out—and Joanna Russ does too—that a lot of the slash stories wouldn’t fit into the canon of homoerotica. Some people would say it’s not about a gay sexuality—it’s about the sexuality of two characters. And yes, it’s about seeing two people with agency who can love each other free of these dynamics of oppression, but there’s also something that approaches the singularity, in making them one thing and one pair.

Leah Victoria Hennessey: Because when you fall in love with someone, you feel like one of a kind, like the last two members of a dying species. When I’ve fallen in love, I don’t feel like a woman among women who has fallen in love with a man. I feel like one of a kind, and that the other is one of a kind, too. And I feel like that’s part of the appeal of slash. It’s people falling in love and being attracted to each other, despite their sexual orientation, or asexuality, or being different species, alien or human.

It’s about obstacles. When I was a little kid, I read something that said, ‘Eroticism is the overcoming of obstacles.’ I remember being like eight and something clicking in my mind, and thinking, ‘Oh that’s the difference between pornography and eroticism.’

I think the most erotic thing I’ve ever seen was at a Catholic Church—a woman was kneeling and receiving the sacrament, and her eyes rolled to the back of her head as she opened her mouth. It was something that she’d been waiting for and finally received.

Leah Victoria Hennessey: That sacrament is theater.

Emily Allan: Because it happens again and again—there’s no resolution.

Leah Victoria Hennessey: I don’t think you can capture that in film because of the way it exists in time. What makes it theater is, that it’s not a single performance—it’s something you’re going to do over and over. You always know when you watch a play that it will begin again.

Tell me about the actual process of writing the play.

Emily Allan: A lot of our ideas our adapted from real slash fan fiction from the internet—The Beatles bit, Morrissey and Marr, and Trotsky and Stalin.

Did you have to ask permission?

Leah Victoria Hennessey: Well, we’ve tried. The thing about slash fiction is that it has an inherently anti-capitalist essence. You can’t capitalize on it, because it’s illegal due to copyright laws. So, the writing process was kind of a curatorial scavenging. There is one funny thing we do—I can’t write a first draft on the computer, I must write by hand. So, what we do is, we sit next to each other and write and talk it out while we’re writing. We will be talking and sometimes we'll pause, and we will both be next to each other sitting and writing the same thing. So, then we have two copies.

You guys are just so in sync.

Leah Victoria Hennessey: Also, I believe that writing is thinking. I need pen on paper—it’s a control issue also. It’s like, subconsciously neither of us trusts each other to get all the words down right. But I can only think of two other times in my life where I’ve laughed as hard as I did when we were writing. I lose my mind, we scream, we throw the notebook, we get so scared, we think it’s the worst, we think there will be riots—

Emily Allan: And then we’re like, ‘Where’s the Nobel? Where’s the genius grant?’

Leah Victoria Hennessey: We get so worked up when we’re writing, and then we crash and get lazy and have to rewrite it—it’s very extreme emotions.

How did you think people would react to the play?

Emily Allan: Up until opening night, I didn’t know if anyone would be able to sit through it. I had a lot of doubt because there was already so much satisfaction in doing it ourselves. Also, I don’t think anyone has laughed as hard at is as we have. I had no idea how people we’re going to react. I didn’t even know if it exists in the real world because the creation is so insular.

Leah Victoria Hennessey: I thought it was funny, but I thought people were going to read it as pretentious and alienating. I didn’t think people would think it was funny. But I was fine with that. I didn’t have high expectations about response. The play makes people happy to watch—I see them come in and I see them leave, and they’re happy. They don’t just say that they liked it or that it was good, but that it made them feel joy.

That’s exactly what I felt! It made me want to go home and write. And I think it’s because your performance on stage is so genuine—it so obviously comes from a place of love and commitment to what you’re doing.

Leah Victoria Hennessey: I think that some of the fear about people not liking it came from knowing that we were revealing a lot of ourselves. I was like, ‘Well, this is me, so people probably aren’t going to like it.’ It felt honest in a way that nothing else I’ve done has ever felt like, and doing the play made me realize how much I discounted things for being too girlish. There’s something indulgent about the fantasy aspect, in a specifically girly way that felt scary. It’s not like a modern guy play—there’s no macho resolution.

There’s no traditional climax, either, which is kind of a phallic idea to begin with. Theater and literature are such male-dominated institutions historically, that when women take that banner, it’s always experimental, because how do you find your own voice? How do you show yourself who you are on the page? A lot of that for me is fan fiction, slash fiction and Slash the play. It’s creating worlds so that you can see yourself in the world around you.

Leah Victoria Hennessey: The fact that girls have been writing fan fiction for so many years and not needing to have it validated by the outside world or get compensated—there’s big problems with that, but it’s also such an inspiring way to get around the fear of being a writer. Like, when I read fan fiction as a kid and even now, I was like, ‘Wow these people are so fearless about putting words out there.’

What do you want people to take away from Slash?

Emily Allan: I want people to think it’s funny, and to whatever extent, I want to get our ideas and sensibility through. So much has been said about this, but taking this slash format that’s so extreme, and intense, and romantic, and adding things to it and making it theater—that allows for moments of lucidity where I feel like I can express parts of reality that I can’t express in real life. Beyond that, I think that the most important thing about it is that it’s a funny show. The most important thing is laughter.

The next ‘Slash’ performance will take place Thursday, December 20. Buy tickets here.