Steak's Memoir Bares All

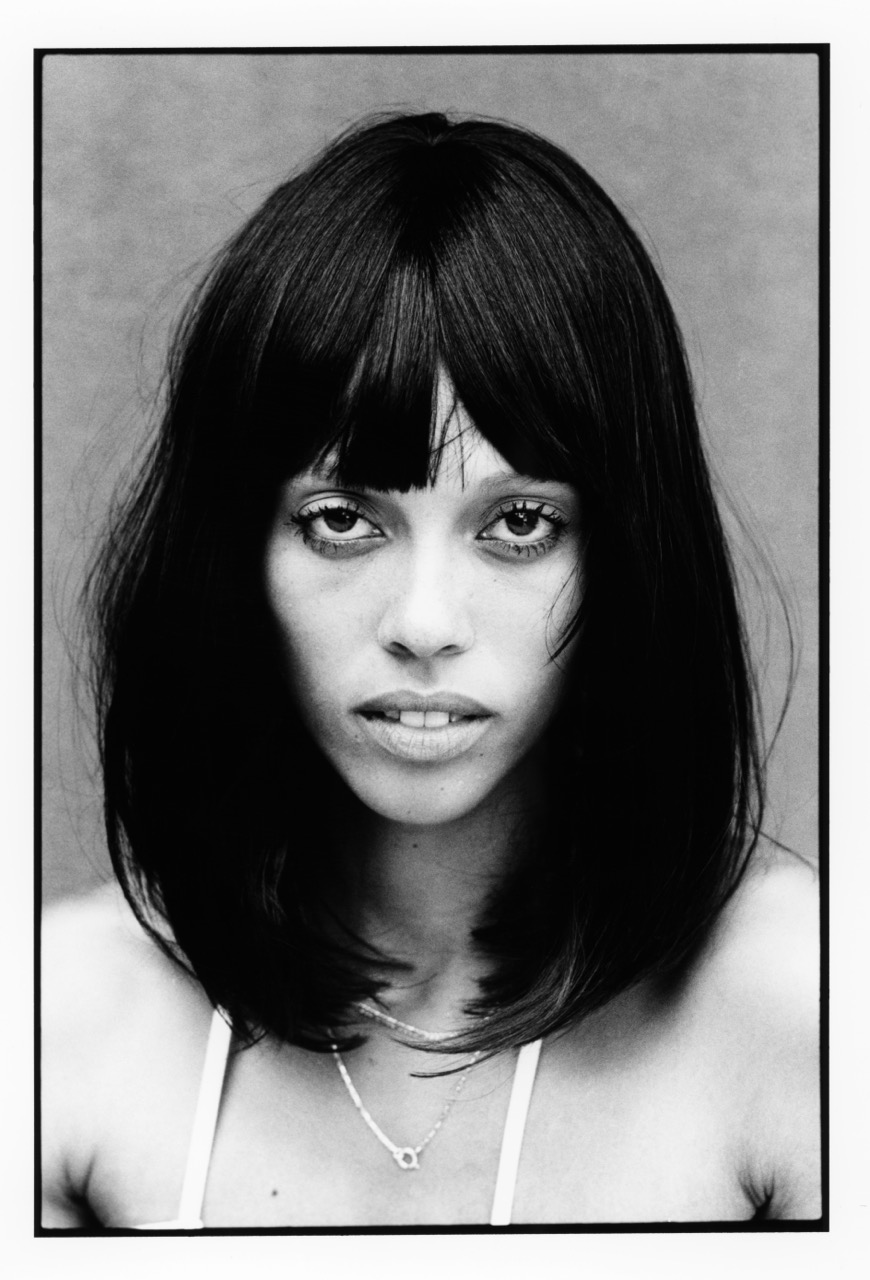

Between a lonesome and challenging (to say the least) childhood with nobody watching out for her; a whirlwind romance with an actor who became her husband, the father to her daughter, and then her ex-husband, business partner, and co-parent; and a grueling cancer recovery that kept her from holding her infant child, Steak has earned the strength she exudes.

Her story tells us a great deal about who she is as a person and what has transpired in order to form the “it girl” we know and love today, but is also so raw and real that it represents her as a work in progress.

“The memoir” as an art may suggest a certain book ending to a creative’s life and career — I have accomplished XYZ, and this is my life story. But the art form is shifting and changing as discussions of what it means to be a person become more nuanced and complex. In Nobody Ever Told Me Anything, Rachael is willing to bare herself, honestly, making it evident her story is not yet finished.

WR— How are you today?

RF— Straight off the bat, I had some work shit. It feels like I’ve been up for 10 hours already, but it’s been a casual Friday morning of pure catastrophe.

WR— Classic! Let’s jump into it. Why did you start writing?

RF— It was definitely the era I grew up in — LiveJournals, and then I was around for blogging. My first real job was social media, when I was 20. I worked at a record label doing their social — that was their blogspot and things like that. I’m an only child who grew up really isolated, so writing was an easy way for me to get things out of my head. I’m not really a journal-er though. When writing, even LiveJournal, which was private, I was writing as though I was broadcasting. I was definitely the kid in the mirror doing my own cooking show, or my own makeup tutorial. A whole world is in your head when you’re lonely. Writing started young.

WR— Did it become a passion of yours early?

RF— I don’t know if it was ever a passion, but sometimes I feel like I can get really emotional when I speak, and I was definitely the kid who would try to discuss being angry and then would cry. It has always been easier to express myself in writing, rather than speaking.

WR— Do you feel there’s any difference between who Steak is and who Rachael is? In other words, has Steak become a kind of alter ego?

RF— That’s a tricky question. In my mind, there is a big division. But, my real life people do call me Steak, and the people who call me Rachael do call me Steak when I’m not around. There are millions of Rachaels in the world, but not many Steaks.

It’s a blended identity, but when I think about Steak vs. Rachael as far as sharing publicly, before the book, yes, very much so, it was different. I’ve always been viewed as being very open and transparent, but you can be open and transparent without giving it your all. It’s still more so than most people are comfortable with, but there is a lot of me that I haven’t shared.

Even the book is heavily edited. That’s the funny thing about the book is I saw a lot of people saying, “Wow, she really said she wasn’t going to say anything, and she said everything!” And it’s like, no, I didn’t.

My sister, who I’ve actually known longer than anyone in my life, including my parents, and I were talking about this. There are so many things in the book that I watered down and made vanilla because they weren’t digestible in other ways. There will always be a difference between Steak, who I think of as the front-facing person, and Rachael. Rachael has a lot of things she’s still working on.

WR— I think it’s a skill in itself to make people feel like you’re giving them everything, when you’re not. Do you think you’ll ever divulge those parts of you? Do you think people will ever be ready, or have you decided to not go any deeper?

RF— In the beginning, when my platform started blowing up, I was really trying to fit into a box and be palatable. This is like 2010, 2011 on Tumblr. I was really trying to be digestible, and everyone was still reading me as very alt and very abrasive. I was like, Wow, I’m trying my best here. I kind of learned to dumb stuff down. When I wrote the book, that was such a freeing moment, because there was stuff in there that I never talked about online. How do you spend hours talking to people online for years, and sharing tidbits of yourself, but never really sharing the full dynamics? The book was a big deal for me. But now that I’ve done the book, I feel really untethered by the things I was so fearful of, and the parts of me I was fearful of sharing because of judgment, or feeling lesser than, or that I’d be too much to handle.

I started my podcast back up — we filmed the first two episodes yesterday. This season on my podcast, my sister is my co host, and I am talking about a lot of stuff I’ve never openly discussed before, in a tone that is more Rachael vs. Steak, I guess. It is really real, and a bit crass. As it was coming out of my mouth, it feels like a normal conversation that I would be having with Liz, but I kept remembering there were cameras there. Before, when I’d put something out that I felt was too much, I’d ask my producer to edit it out. But now, I don’t feel weird about it, and I think that’s because it started with the book.

WR— I do think people will really respond to that, because people respond to honesty and realness in that way. Even if it’s scary, I think it does a lot of good to let those things out.

RF— I always make this joke with my friends: A lot of life really felt like an SVU episode, but really it was just a Sex and the City episode, and it’s the same plotline, but it’s told differently. I just felt like that perspective change happened through healing and becoming more comfortable with the person I actually am. It’s not like I’ve lied to anyone, I was just always guarded. I was with people that I also wanted to guard from the repercussions of being my friend or partner. I realized through everything, all the people I was afraid of ruffling their feathers, they’re all still here and in my corner.

WR—Why write a memoir now? A memoir can suggest—

RF— Finality?

WR— Kind of. It doesn’t have to, but what in your life made now seem like the time?

RF— I tried to write this in 2012, right when my mom had passed away. It says a lot about processing grief, and all the anger and resentment. In 2016, I tried to take a stab at it, when I was going through my divorce. I realized, "Oh, I’m not writing for anyone else, I’m just angry writing. This is processing writing. It wasn’t clear-headed." I became very aware of my tone. In that moment, it was fucking piping hot. That was great for processing, but that’s not honest to the story. That was a blip of a feeling that can be included in the story, but that’s not an overall accurate capture of what was actually going on at that time.

I kind of knew I wanted to tell this story, mostly because, with the loss of my mom and it being just me and her for so many years, I think I was feeling like I was losing her a bit. My memories were fading of her. Once I started writing, I started remembering a lot of shit I’d forgotten, as kids do. That was really cathartic for my grief process. It just kind of started there.

I think you can read in my words that I’m angry for my mom. To go back to finality, like, I have accomplished the thing, and now I’m ready to write it — in the book, it ends, and this is a hard part I’ve seen people struggle with in reviews — like, Well, she was in a relationship at the end, and now she’s not in that relationship. That’s the point. It still goes. I tried to leave it there. You can see a very consistent pattern.

Full disclosure, my partner from the end of the book and I ended things officially the day of my book release. When I took myself out of my being, and saw this character that I’m writing, like, "Of course, she wouldn’t be in that relationship anymore." That wasn’t the point. The point wasn’t, "Now she has a boyfriend, and her life is perfect." You can still see the flaws. If I’m talking about it in a third person way, you can still see that she hasn’t yet healed the bullshit. She’s still doing this thing over and over again. I think it makes more sense that I’m not in that relationship. It wasn’t supposed to be final. It wasn’t supposed to be the end, or to be complete. It’s just supposed to be: this is who she is today.

WR— It makes the book that much more real. Life does go on. I don’t think it necessarily has to be thought of as a bookend. The art of memoir is changing from being such a rigid structure. I think your book subverts that idea.

RF— I hope so. I tried to write it as honestly as possible. How I was experiencing things. There are times in the book where you don’t like me, and that’s okay. I didn’t like myself at that point either, and it was hard to write about. I was a demon, I was chaos, and I was stepping on people’s heads, and that’s not okay, either.

WR— How has writing about your trauma affected how you perceive or process that trauma?

RF— It’s like an accordion. It ebbs and flows. Sometimes putting something into words can definitely make it feel analyzed. It’s there, I can look at it, I can say it in a sentence. But, just like I was saying, with emotions and anger-writing, tomorrow I might feel free of it, and today I might feel bogged down. I don’t think anyone is ever free of their trauma; I think it’s always living within them.

Writing it out definitely helped me get it out of my head. You’re in your own echo chamber. Even just my editor reading it, I felt very seen. In the most selfish way, the book is very much so for me. I needed to write that out, I needed somebody to listen to it, and be, like, "Yes, I see this shit, and this shit sucked."

WR— Looking at it on a page, were you able to see it as something separate from yourself? I feel it can be helpful to view trauma as not necessarily part of you, but something that happened to you.

RF— It definitely helps with that aspect. Seeing it as something that happened, versus stuff in your purse you have to lug around. It seems more processable, but tomorrow it might not feel that way.

WR— If the time since you finished writing the book in May 2022 was an added chapter, what would it be called?

RF— “HOLY SHIT!” If you follow me on Instagram you can see I’ve been going through a lot of changes. My photos I post without sweating too much about how my skin looks, I look less depressed. And, like, I’m getting married in June. I had known my current fiance for a long time, but for some reason, in the middle of this, I was like, "Yeah, I’ll go on a date." It was everything all at once, for me.

That was a very whirlwind situation. By January, I’m engaged, and then, you know, "Who the fuck knows what’s going on now?" Now we’re looking for another house! What’s going on? It’s definitely a "Holy Shit" moment.

Here’s one thing the book really brought me. I talk about not being defined by the men in my life, because that’s something that is consistently prescribed to women. It really irks me. There’s this piece I talk about, that I have no family. I have no one else. The people I’m closest to are the people I’m in the relationship with, so it’s hard not to tell stories or timestamp things with that.

WR— Those people become your family.

RF— Yeah, you anchor there. People will say that’s flawed, people will say that’s whatever, but everyone’s living differently.

WR— You can’t say that’s flawed. It’s your reality. Every single person’s reality is valid. You can still decenter men from your life, even when that is your case. You’ve done a good job of that in this book. I guess it is time stamped that way; you can measure time that way, and I think everyone kind of does. Our relationships define periods of our lives, right?

RF— With that, I want to say, through writing the book, it was the first time I realized this mathematical pattern with the types of men I’m dating, and what I’m doing. It’s whoever appears textbook safe, and got a job. Tattooed or not. But he’s got really repressed bullshit that he’s not working on. Then it’s like this other one is a fucking gangbanger. It’s a pendulum. At the end of the book, it’s almost a blessing that that relationship ended in such a poetic way on the book’s launch day. This pattern I’d been chewing on since June, that I realized when I finished the book, I could finally deconstruct. I needed to deconstruct my being and figure this out. I didn’t see it as a flaw, but I saw it as something that clearly was not bringing me joy. As far as titling this chapter, "Holy Shit!," I’ve really been fucking myself up trying to make myself go through all of that. What I’ve brought to the table in those situations — I’m not a victim — I was bringing in my baggage, as well.

WR— What else did writing this memoir teach you about yourself?

RF— I think I realized things I thought I was fine with, I really was not. Things that came out the most seething, and I had to edit down. Like the stuff with my mom’s family. I could’ve eviscerated them, and I did in the first version. But I had to come back to it and take all of that out, and make sure it wasn’t angry-lunatic-writing. I was in a headspace that they didn’t affect me, but obviously they did.

This is where I have compassion for myself. Obviously, I’m in a new serious relationship — I’m always in a serious relationship — so maybe that’s part of the pattern I’m willing to accept about myself. There’s parts of it I want to fight, and parts of it I actually enjoy. Sometimes things people deem as my flaws, I actually like myself.

WR— People are quick to pass judgements on people who fall in love a lot, or people who are in relationships a lot. I was just watching the Pamela Anderson doc, and she’s been married a ton of times. But is that actually a bad thing, to love to fall in love?

RF— Exactly. I’ve learned to have compassion for myself, and that I still have a lot of work to do. I’m not in my final form. It challenged my identity.

WR—Do you feel any less guarded after writing it?

RF— I don’t think I’ll ever be that person crying on Instagram, which is very vulnerable. I always give a beat before sharing. That isn’t representative of how I am in real life. In real life, if I have a feeling I’m talking about it before I’ve even thought it through. There’s still some fear in me about that.

WR— How do you balance co-owning a company with an ex, as well as co-parenting? Was he affected by what you wrote in your book about the relationship?

RF— I gave him the book before I put it out. I don’t recommend anyone ever work with their ex; it’s a terrible idea. Here’s the thing: we do it in a way that’s really crazy. We talk six times a day. Maybe it would be healthier for people to excommunicate exes, but the fact of the matter is: we were very entangled in each other’s careers, and we have a child together. There’s a level that you cannot untangle once a child is involved.

Blake and I are friends, you know what I mean? We talk all the time. I did give him the book before I published it. I don't know if he read it, if I’m honest. I don’t know if he really wanted to get into that. Blake and I grew up together. We were in our young twenties together. That is a stupid time to be co mingling with people. You go through shit together. What I wrote in the book — I get it’s celebrity, and there’s this tabloid-ish, clickbait-y nature of being like, "It was fucked up!" But that’s another case of, like, what I wrote was about how it affected both of us. His anxiety, which is very present. I wasn’t trying to write myself as a victim. We were both vastly misunderstanding each other because we were fucking twenty, and the whole takeaway of the book is that this is what happens when you have people around you, but not a community.

That’s what happened with my mom. She had no community. Blake and I had seven people on our payroll, we had everybody at our house all the time, we had house parties every weekend, we had people calling us all day to hang out. When our shit was not functional or one of us was struggling, we had no community. That’s what I was trying to write in the book. He ultimately understands that deeply. We went through that together. There were times when I broke his heart because I didn’t see his potential, that he was really trying to work on something and be this star. I fucking hate fame, and I was so angry. It was just stupid. We were dumb, drunk, and 24. In a lot of ways, it’s brought a softening to us.

At the end of the day, it’s 10am and I’ve already talked to Blake today. We are not enemies. We’ve been divorced for 8 years. We’re not the people we were when that happened, because we have worked through that. We’re the people we are today to each other. It’s also psychotic and I don’t recommend doing it — working with your ex.

WR— You were going through cancer recovery and radiation with a newborn infant. How did that experience affect or change you? What do you think that gave you as a mother?

RF— Not being able to breastfeed her: one school of thought is skin-to-skin contact and you must breastfeed. Seeing my child at nine, thriving despite that, and realizing the devastation I felt over those things doesn’t define me as a mother. I feel really sad for the 26-year-old me, who was vomiting, going through radiation, wearing a hazmat suit, just trying to touch my baby. Being locked in a room terrified she’d grow up and not care about me, and we’d never be bonded. I spent months sobbing up in that room, thinking I’d ruined my little baby. Realizing that wasn’t real has offered me a lot of perspective, not just on motherhood, but in general.

WR— You’ve written about how you were very underparented. Did this give you the inclination to over parent? How did you deal with that?

RF— I still openly struggle with that. The other day, my daughter said, “Mom, you treat me like trash!” I, like, died forty-five times and called all my close people. Hearing that gutted me. Two days later, I was standing behind her. She was on Youtube watching something that was going, “You’re trash!”, “I’m trash!”, “You’re calling me trash!” That extreme guilt when she feels any sort of disruption or discomfort is something I’m still working on, actively. A lot of that comes from those radiation treatments and not being able to touch her and being a crazy person, locked in a room.

WR— I cannot imagine.

RF— If you have milk in your boobs, and you hear a baby cry — it doesn’t even have to be your own baby — your milk will soak your shirt. When it's your own baby, and you can’t touch her… I was trying to act normal, but having psycho thoughts alone in a room all day, vomiting and pacing around. It’s making me want to cry.

WR— It genuinely sounds like torture.

RF— It was truly torture.

WR— It’s primal.

RF— The most primal thing I’ve ever experienced. The suit I was wearing was essentially a medical version of dish gloves. It’s hospital blue. I held her in that, and I couldn’t feel her, because it’s rubber. I still tried to make the most of the moment. I could only hold her for timed intervals. A minute here or there. That went on for… probably the first three months. I couldn’t be around Blake either. I was alone.

WR— I’m so glad you got through that.

RF— Cancer while you’re pregnant does happen. If I'm going to give a shoutout to anyone, there’s a ward at Cedars Sinai for maternal cancer patients. If I hadn’t witnessed other women going through what I was going through, I would have thought I was insane.

WR— Who will your memoir help?

RF— Something I struggle with in the industries I’ve been in is that a lot of the people I’m surrounded by come from a lot of wealth. It’s not open wealthiness. It’s secret wealthiness; they don’t even admit to it themselves. It’s like those memes of art kids pretending they're broke. They’re all brand owners, and it’s like, "How the hell did you get 30 grand to run ads?" You know? It’s that. I mostly hope whoever finds my book in this world is somebody out there as an adult feeling less than their peers because they didn’t have the support their peers have. It’s not even financial support, it’s literally just somebody to call if you have a fucking flat tire. That’s who I want to find the book, and be like, "Oh, I can still move forward. Life can still happen for me. I just have to acknowledge I can’t compete with the people around me because they don’t have the same set up as me. So I just have to compete with myself."

WR— How did you learn to deal with that?

RF— Everyone compares themselves to their peers. I’m not free of doing that, but when I started figuring that out and actually looking at stuff, and realizing people were more supported than I was, that’s why they were doing things at 25 that I’m doing at 35. It’s just time and experience that’s given me a little bit of perspective on that.

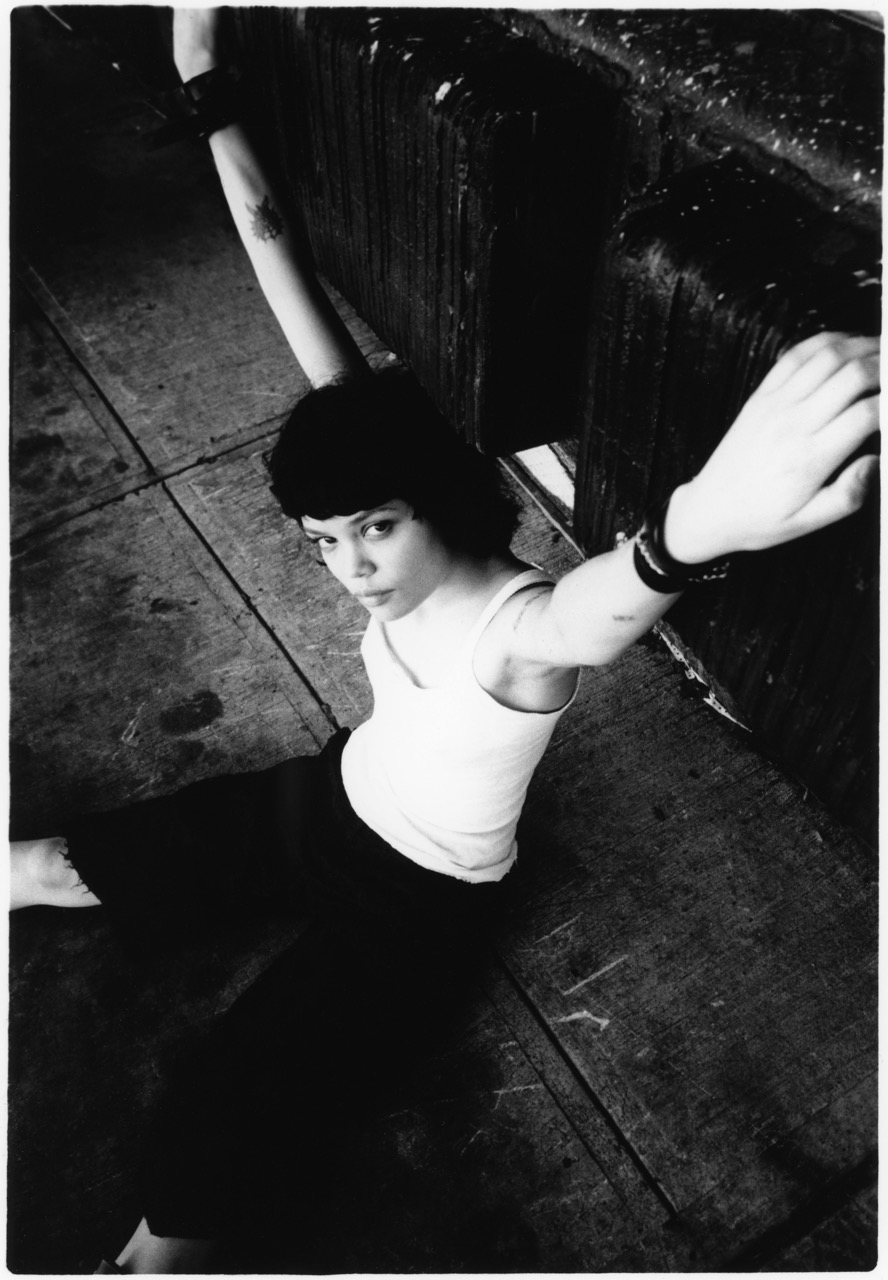

WR— How did you find your style?

RF— For years, when I came to LA and saw what was popular, I was trying to emulate the things I was seeing around me. I’d see pictures of myself and hate them, because I just didn’t look like me in the end. I was trying to look like the people surrounding me because they seemed put together and like they knew what was going on, when I felt I was, like, I snuck in here, and I just gotta be quiet so nobody notices me, even if I was invited. Like, "Holy fuck, they don’t know I was in jail last year!"

I had this really freeing moment when I was burning my life to the ground in 2016 because I was angry, and LA had really burned me for what I thought it was at that time. I started dressing how I did when I was 15. Big 3XL Sweats and big T-shirts. All that confidence that had been stripped away from me after a decade of being here came flooding back in. It was almost too much. I was like, I’m the fuckin’ boss. Just accessing my true inner self. Now that I’ve figured out who I am to the best of my ability as of now, style comes so easily to me. Now I just know what I would wear. Things don’t feel like risks, it’s just like, "I’m wearing that today, period."

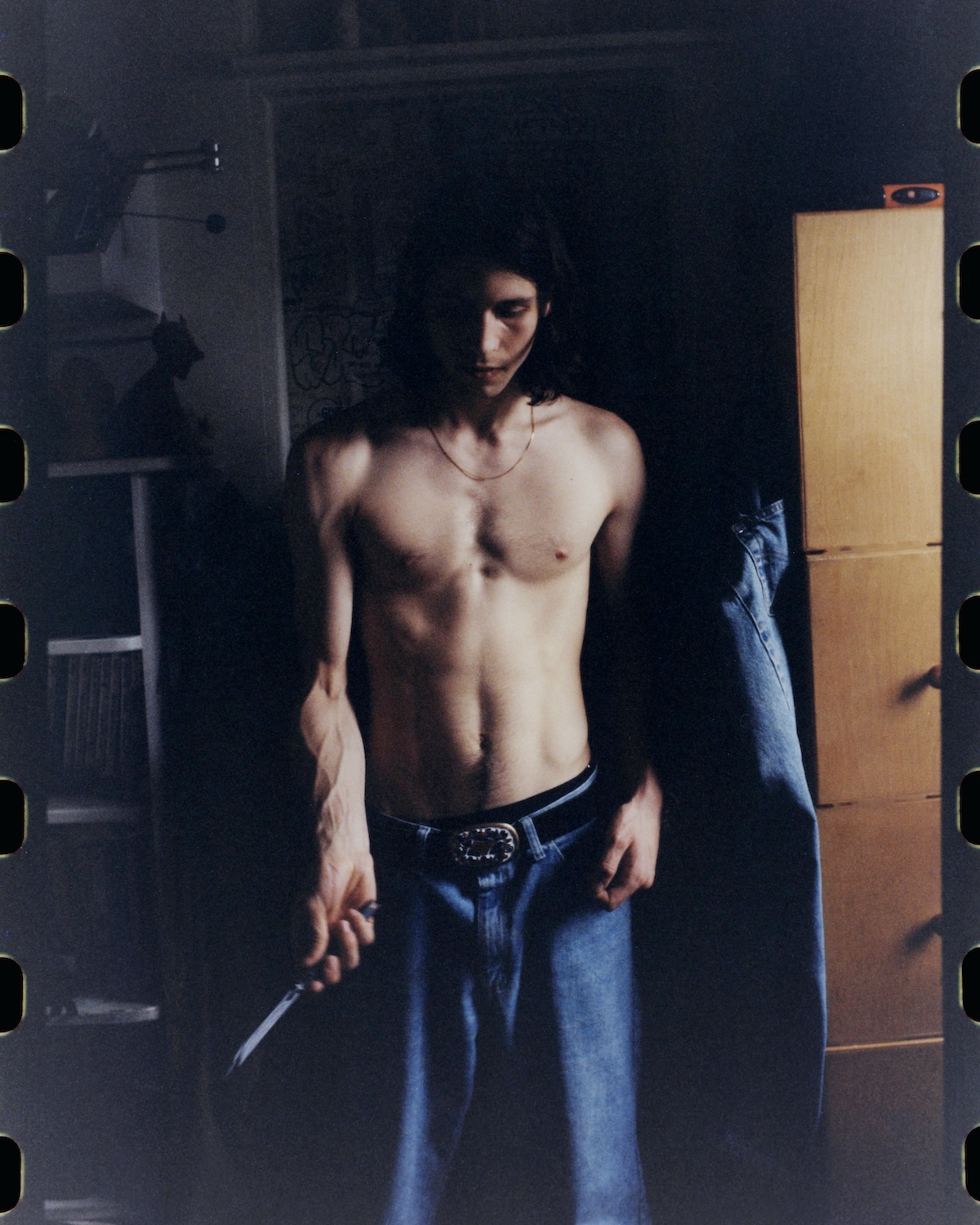

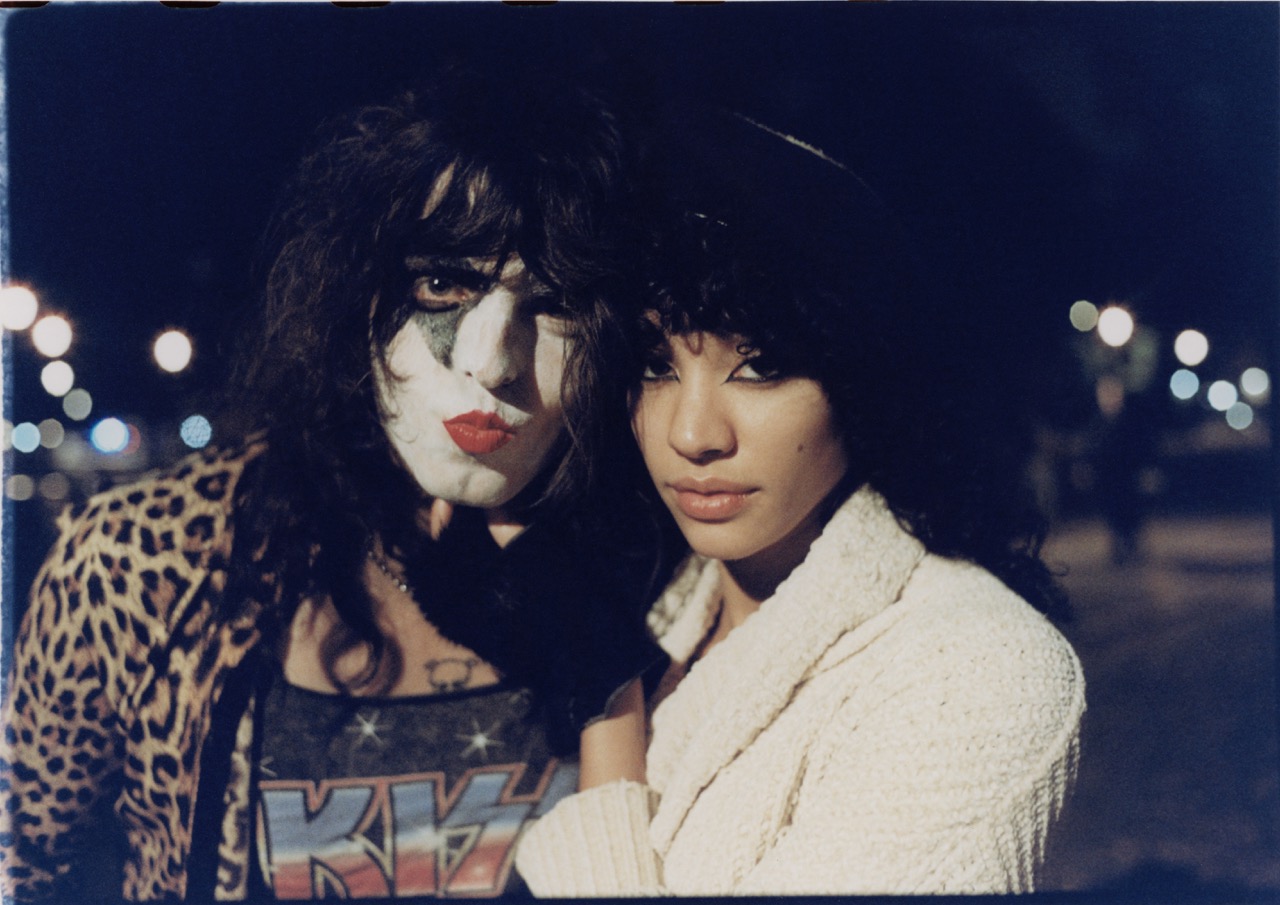

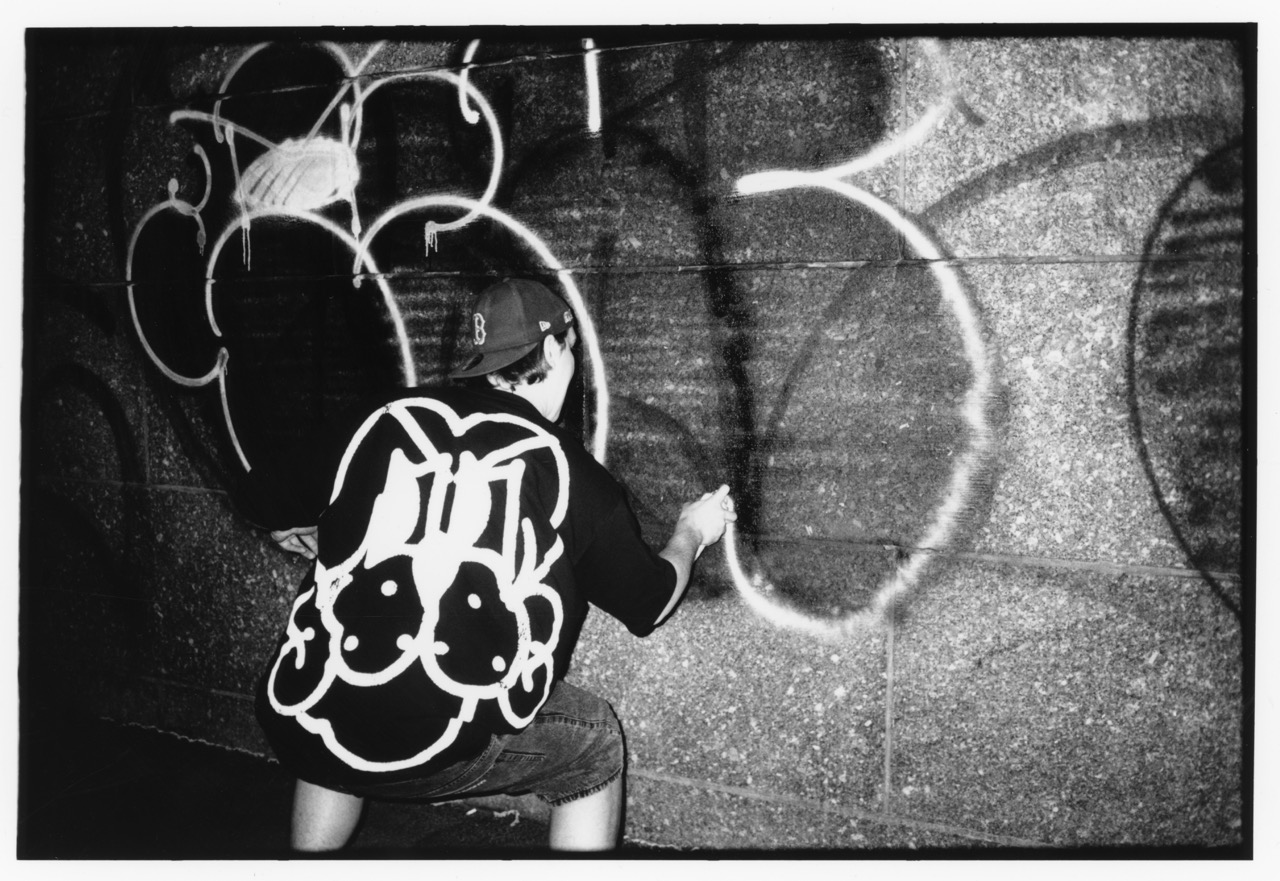

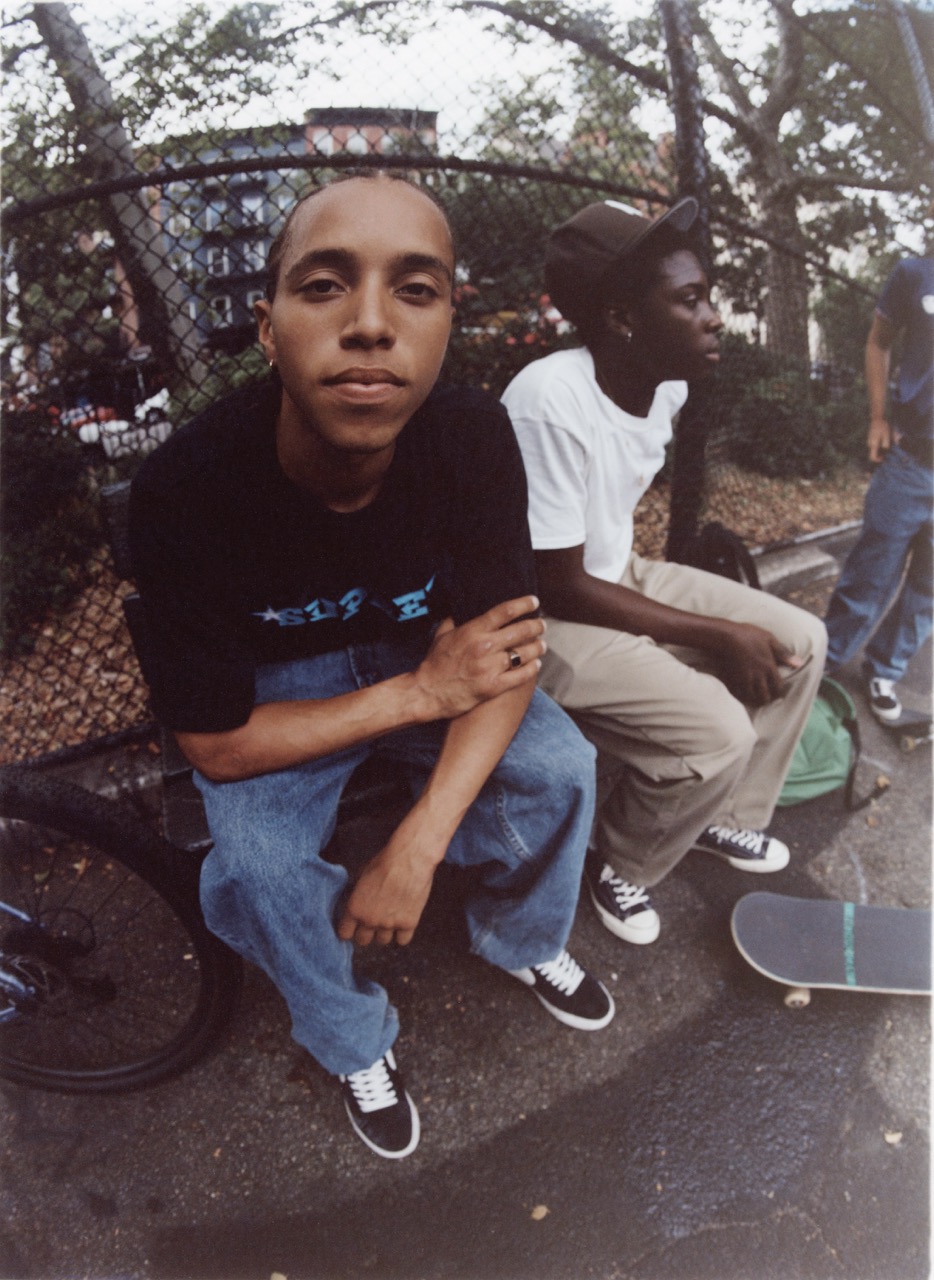

I’ve always had this theory, when we’re teenagers, we are dressing in a way that’s like, "We’re About This." Your band shirts, your skate gear, struggling to identify with the people around you. When you grow up and realize who you are, you don’t have to prove yourself a part of some identity, because you are your identity.

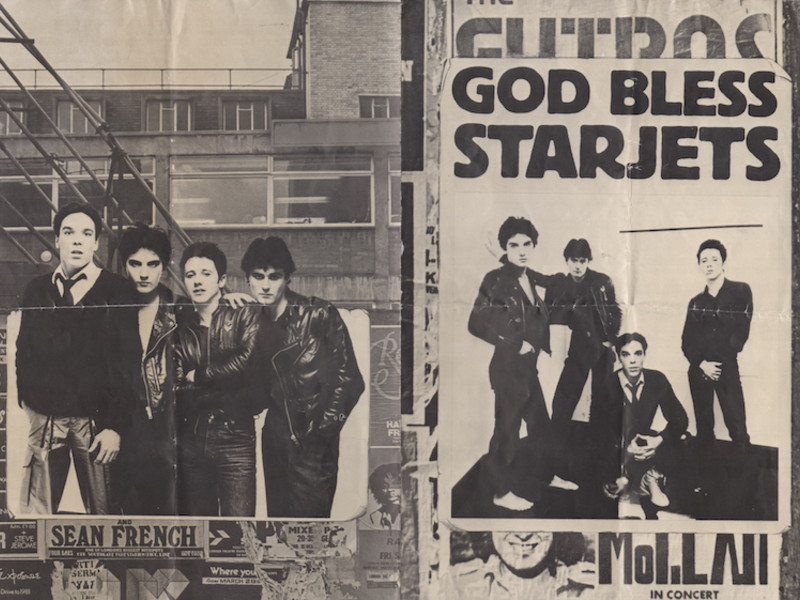

WR— What is the brief origin story of Hot Lava?

RF— Hot Lava is an algorithmic experiment that I made up for my followers. My strength is in brand identity. That’s why people hire me. Hot Lava is based on a decade of my base telling me where they go to eat, the boys or girls they want to date, what concerts they’re going to, etc. Basically pumping me full of data. Hot Lava is what I did with that data. I made it for my base because that’s what they identify with. Very much so me, but I don’t consider myself a designer. Brand identity is algorithmic.

WR— How would you describe your brand voice?

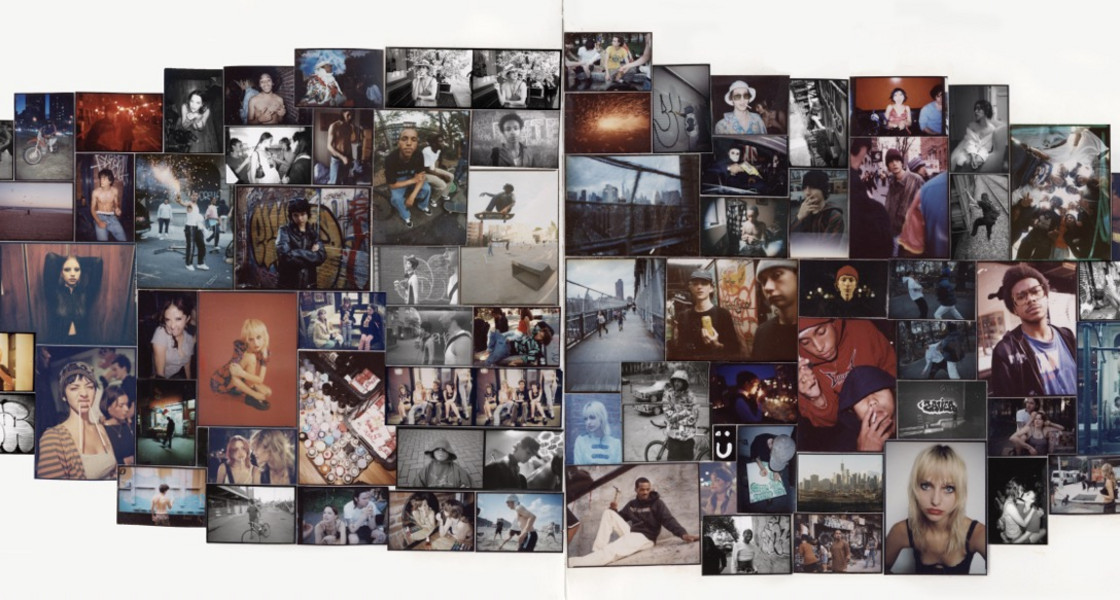

RF— It’s very representative of my ties to skateboarding. Most of the girls that wear Hot Lava skate. It’s a skate brand that isn’t like the other girls skate brands. Granted, now there are a lot of really cool– like Glue is amazing and a really cool skate brand. In 2015, when I started Hot Lava, there wasn’t anything like that. It was just rebranded men’s brands on a slimmer fit t-shirt. Nobody wanted that. It’s very much so girls who are immersed in some kind of subculture. Art girls, girls who go to shows, they juggle, I don’t know! They all have a crazy hobby that’s a little bit different. Those are my people.

WR—Having worked in so many male-dominated spaces, how did you assert your presence?

RF— I’m a girl’s girl. That being said, I’ve primarily been brought up in male industries and by older foster brothers. It’s my main source of information, and the way I communicate in work spaces, I need to work on. Because men in work spaces don’t communicate well. They’re very emotional, honestly, they don’t read other people well. It’s not that I struggle to be heard in those spaces at all– I did not. I’ve more so had to soften and professionalize over time rather than scream to be heard.

WR— You were already assertive.

RF— Yeah, I’ve always been really assertive, but I’ve also had to learn to navigate the fact that I’m a bitch, but Tom over here has said the same sentence and he’s strong and powerful, but I’m an emotional bitch. A lot of navigating that, and making sure I’m not repeating cycles I’ve seen, heard, and experienced to other people, especially as an employer.

WR— How has your definition of LA changed over the years? What is sobriety like in LA?

RF— I had a terrible experience in the beginning of trying to get sober in LA. I was trying to get sober for the wrong reason, I was trying to prove that I wasn’t as much of a problem as the other people I was drinking with. That’s an ugly approach to sobriety, that’s angry. I went to some meetings and let some people I didn’t like define the program for me. I left meetings, and have been sober since. Maybe I’m realizing I’ve been sober without alcohol and without party scenes, but I still need to do a lot of work on myself, whether that be in the program or through trauma therapy, that I’ve been doing for a couple years.

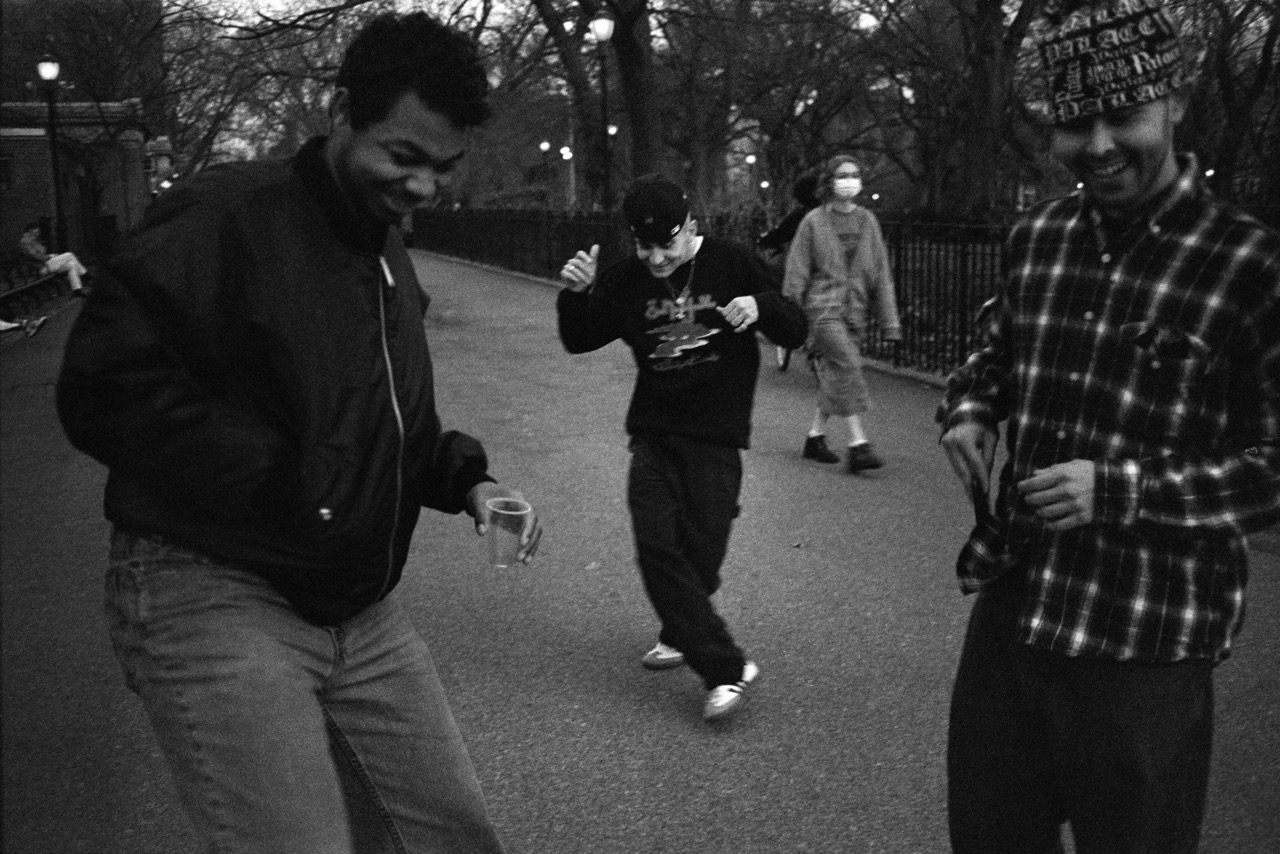

Seeing the city as a sober person has made me completely relearn the city. This is not the LA it was to me when I was at the bar. I eat different food, I go to different places, I engage with different people. I get the fact that people hike now. I still don’t want to hike. Please don’t invite me, but I get it. It’s beautiful outside. I’ll be in a pool chair, though.

WR— As someone who is labeled as an “it girl,” what do you think makes an “it girl” an “it girl”?

RF— Everytime people write that I’m like, Really?! It’s a crazy compliment. I think one thing they have in common is at one point or another being the female villain. That was messy, that was yucky, she did a bad, but somehow they’re still letting her around. There’s gossip surrounding them. After that, I can’t really say. I don’t worry about it, because whatever I’ve accidentally done that’s gotten me this title, I’m just going to keep accidentally doing it. If I pay attention to it, I’ll mess it up. I’m such a boomer mom.

WR— Not at all. That might be one of the things — that they’re not trying to be an it girl.

RF—They’re scared to try, ‘cause they’ll mess it up. Only option is to just keep doing you.