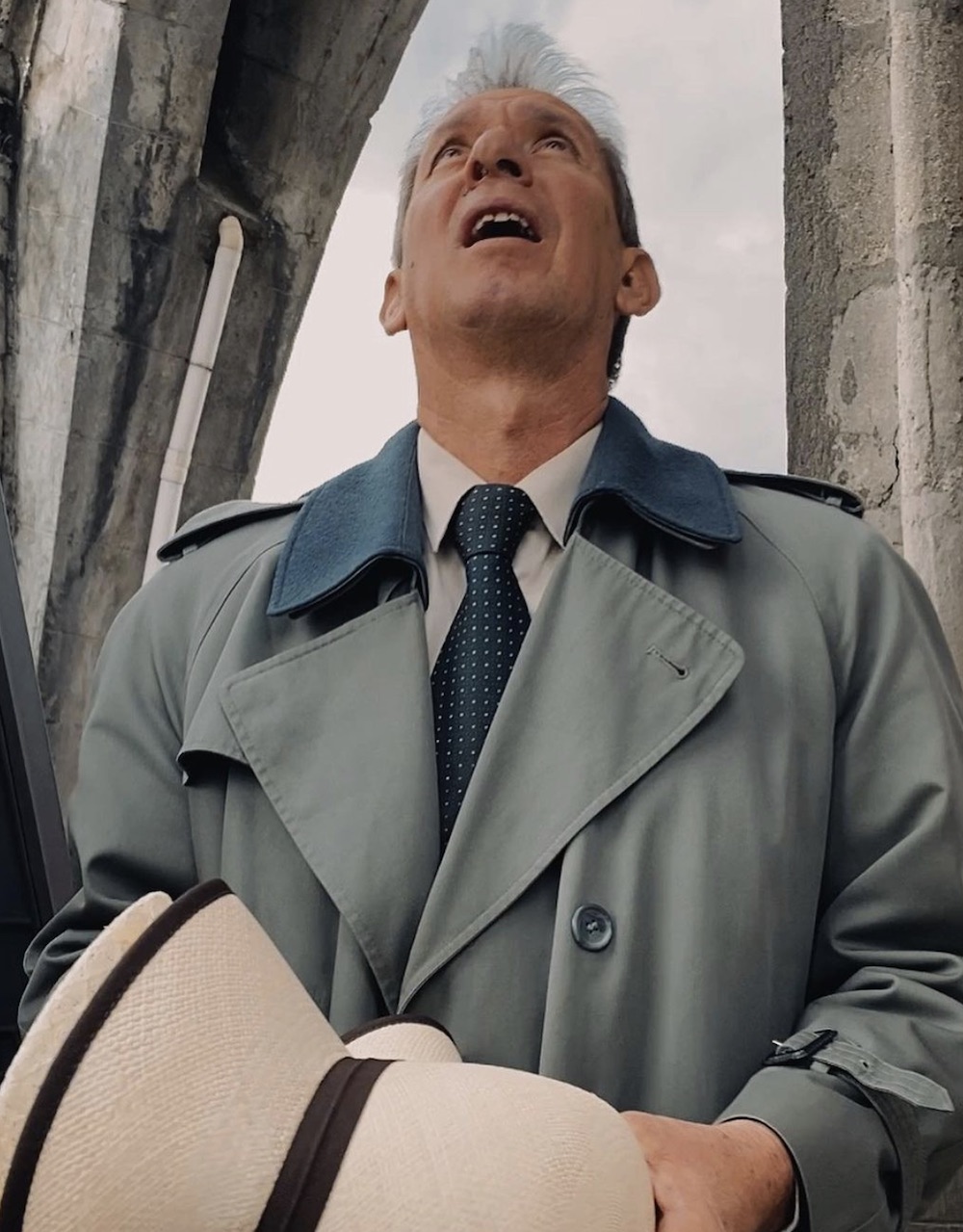

Under the Scalpel with Panteha Abareshi

Can you talk a bit about your latest residency with Human Resources?

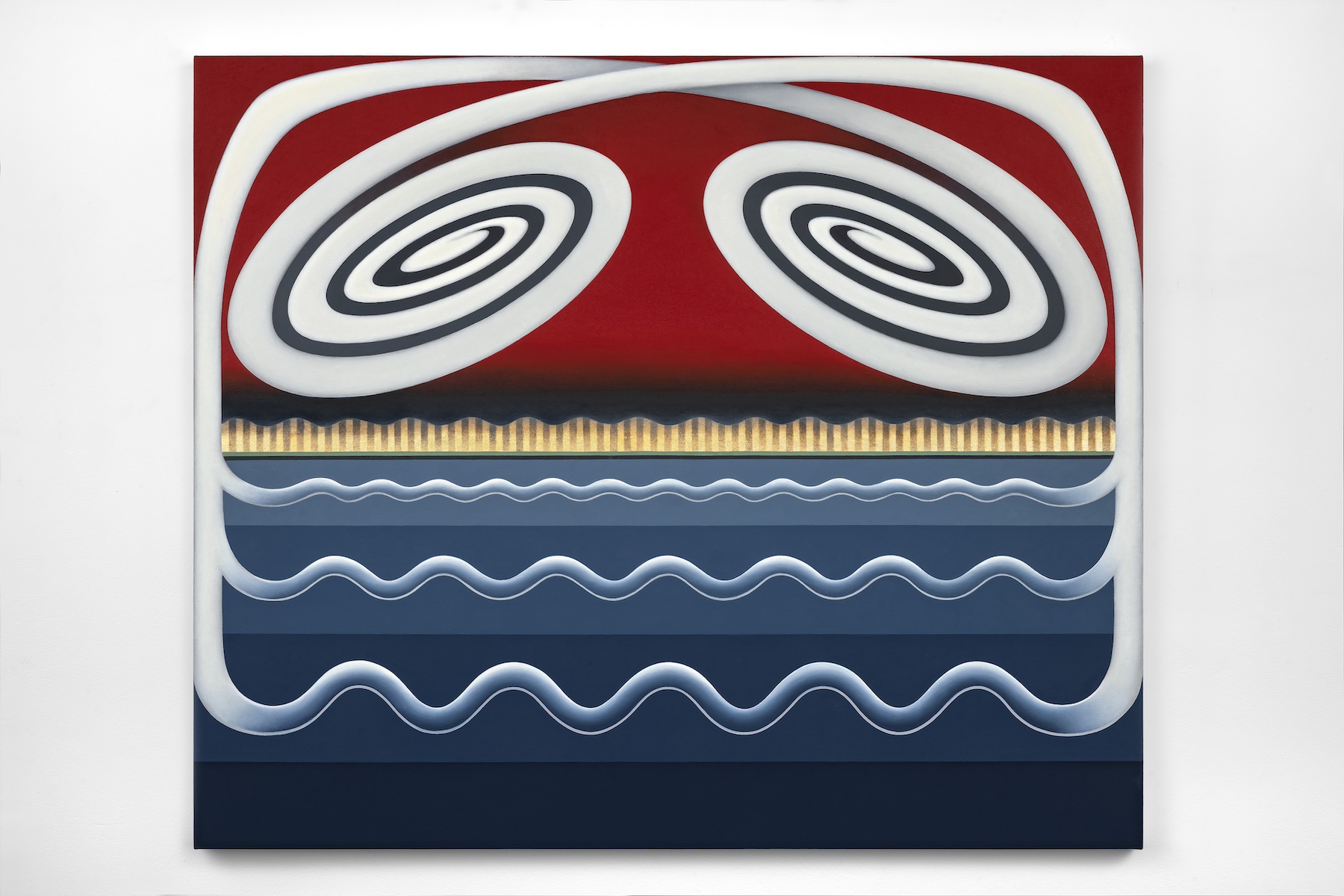

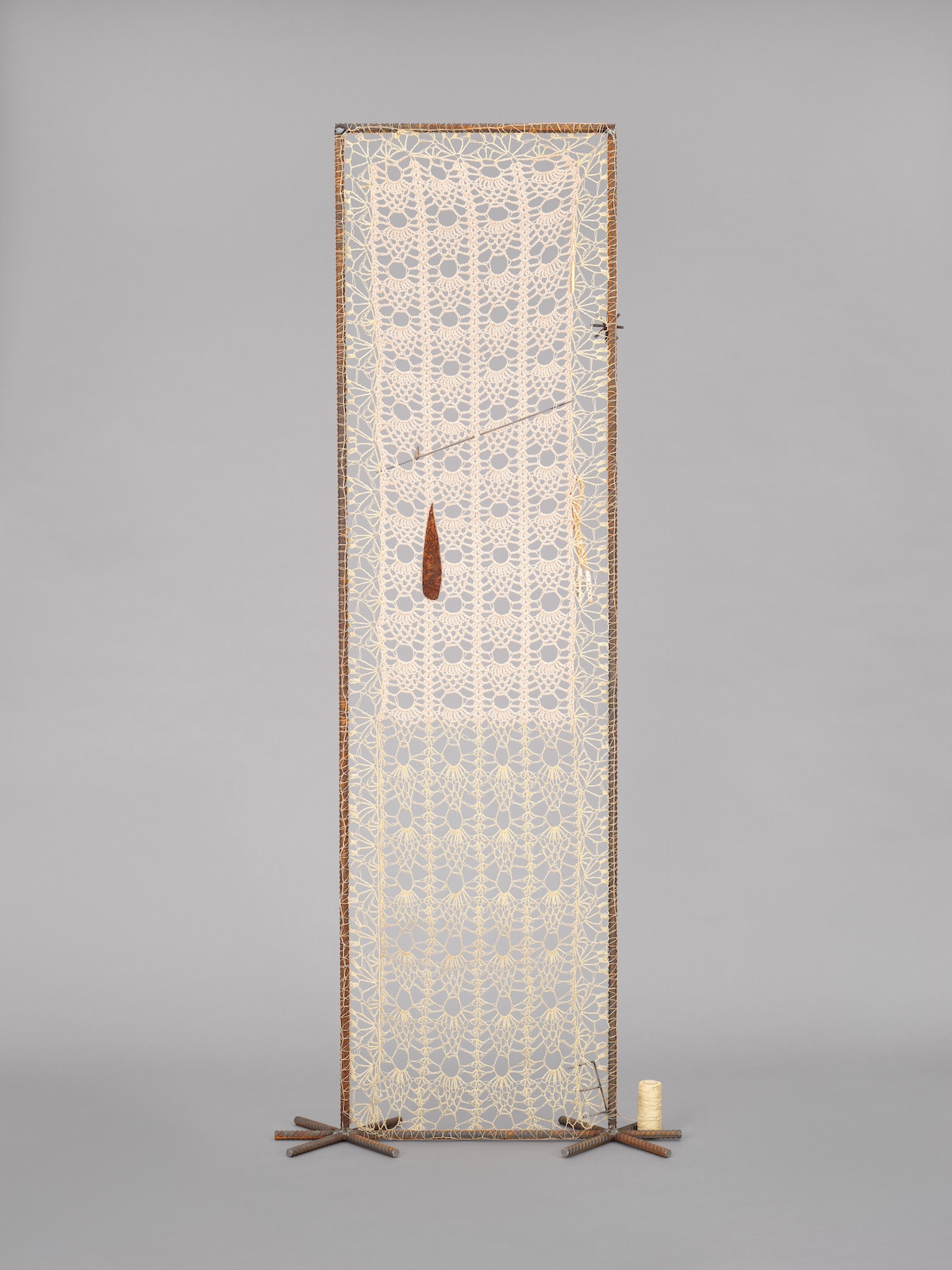

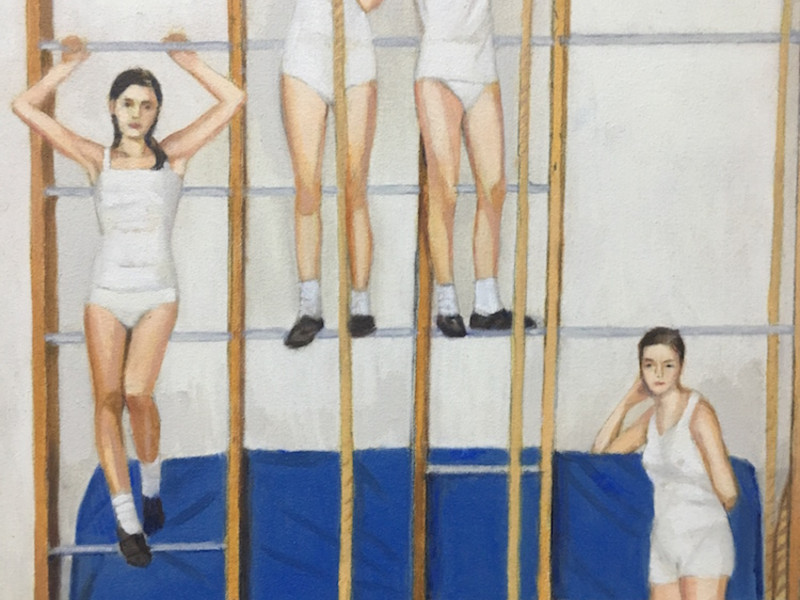

The residency itself is called the Time, Space and Money Residency. It’s been almost exactly a year since my last solo show, HIPAA Violations, so it’s interesting to note how markedly different my work is now. So much of the past was about imbuing my own identity into performance pieces. Now, instead of exploring illness as it relates to my body, this latest project is more a study of The Body—capital T, capital B—and its abstraction. I’m trying to approach this expression of the human body as defunct, restrictive, and inherently violent idea—from a place removed from references of my own hyper specific emotions and memories.

What does that look like in your work now?

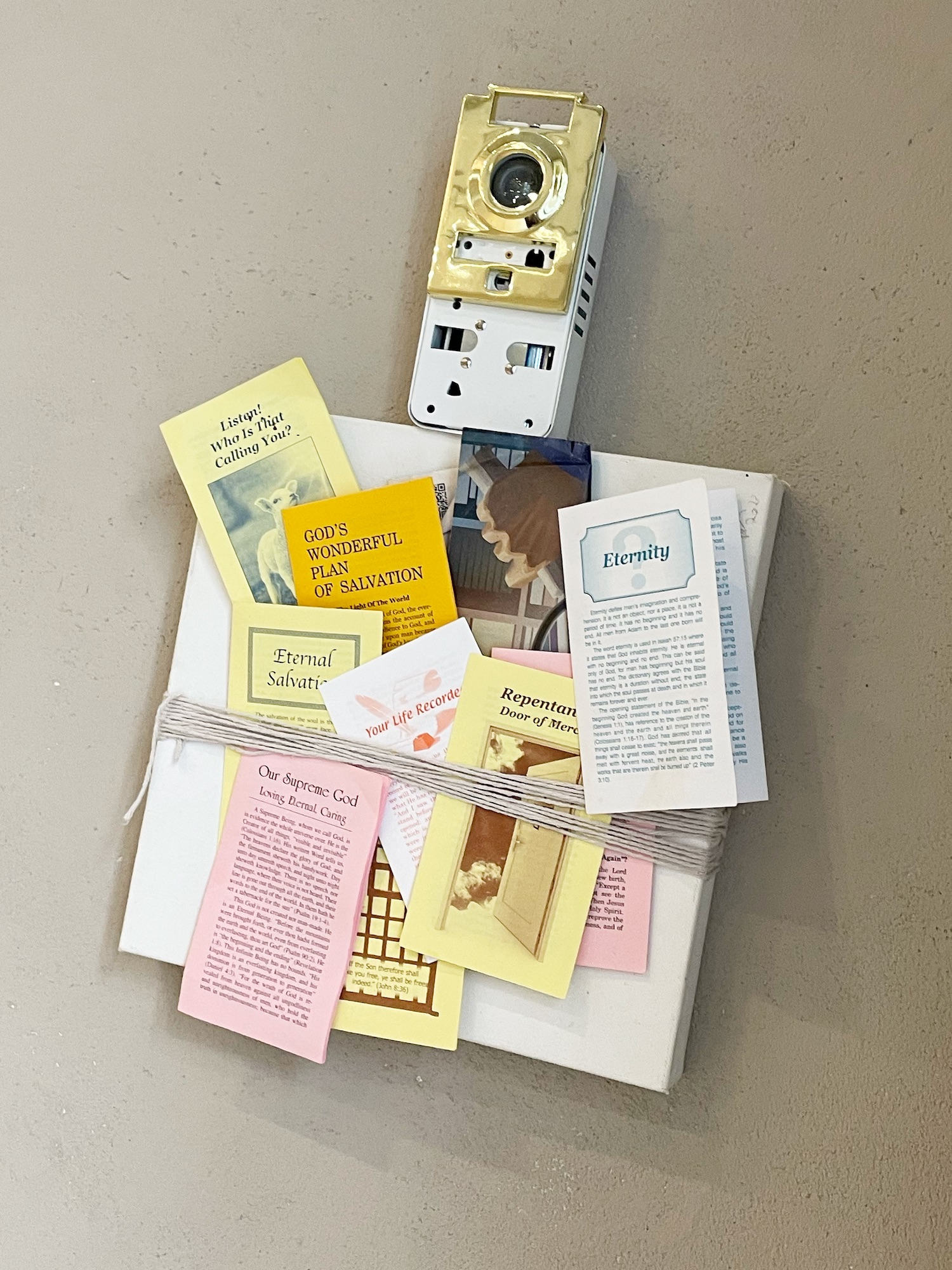

I’m doing more sculpture—a lot of my past work involved integrating medical ephemera used on my body, and turning that into sculpture—whereas now I’m actually fabricating things. Specifically taking medical devices, like mobility aids, and taking them apart and making them into new things. So, still in the same vein that I was doing it before, where I'm using all sorts of medical materials. The difference is now I'm actually turning them into materials instead of recontextualizing them into sculptures.

How do you integrate violence into your performance pieces?

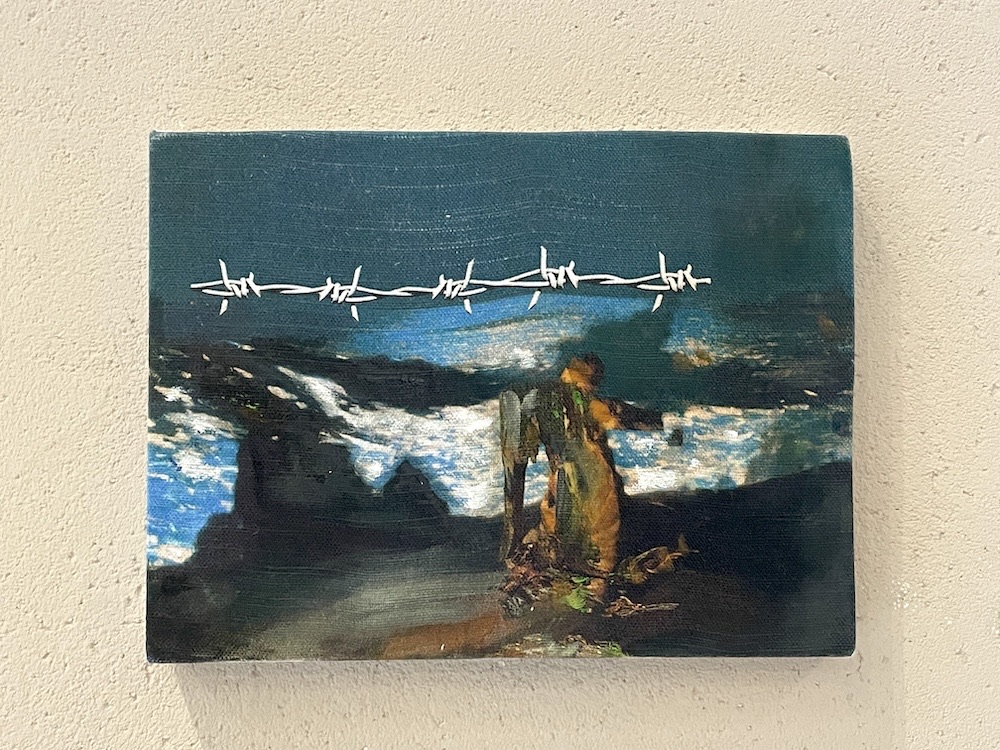

The idea of brutality and violence is so deeply rooted in my work. I think that violence is in every part of language; it's written into the way that we are intimate with one another, in the ways that we have standards around care. Even separated from illness—separated from the body as something that's experiencing violence at the hands of the the Western medical world or at the hands of its own biological system attacking itself— but completely removed from all of that, just being able to acknowledge that humans are so inherently emotionally carnivorous. I want to be able to express that without it being moralistically tainted, it's not about whether it's right or that it's wrong, it's beyond that.

Do you mind talking about how anger functions within the process?

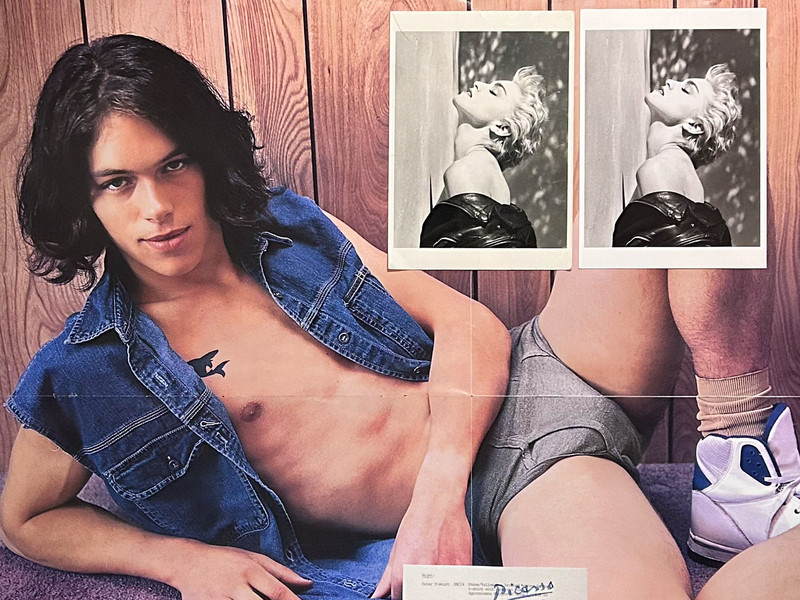

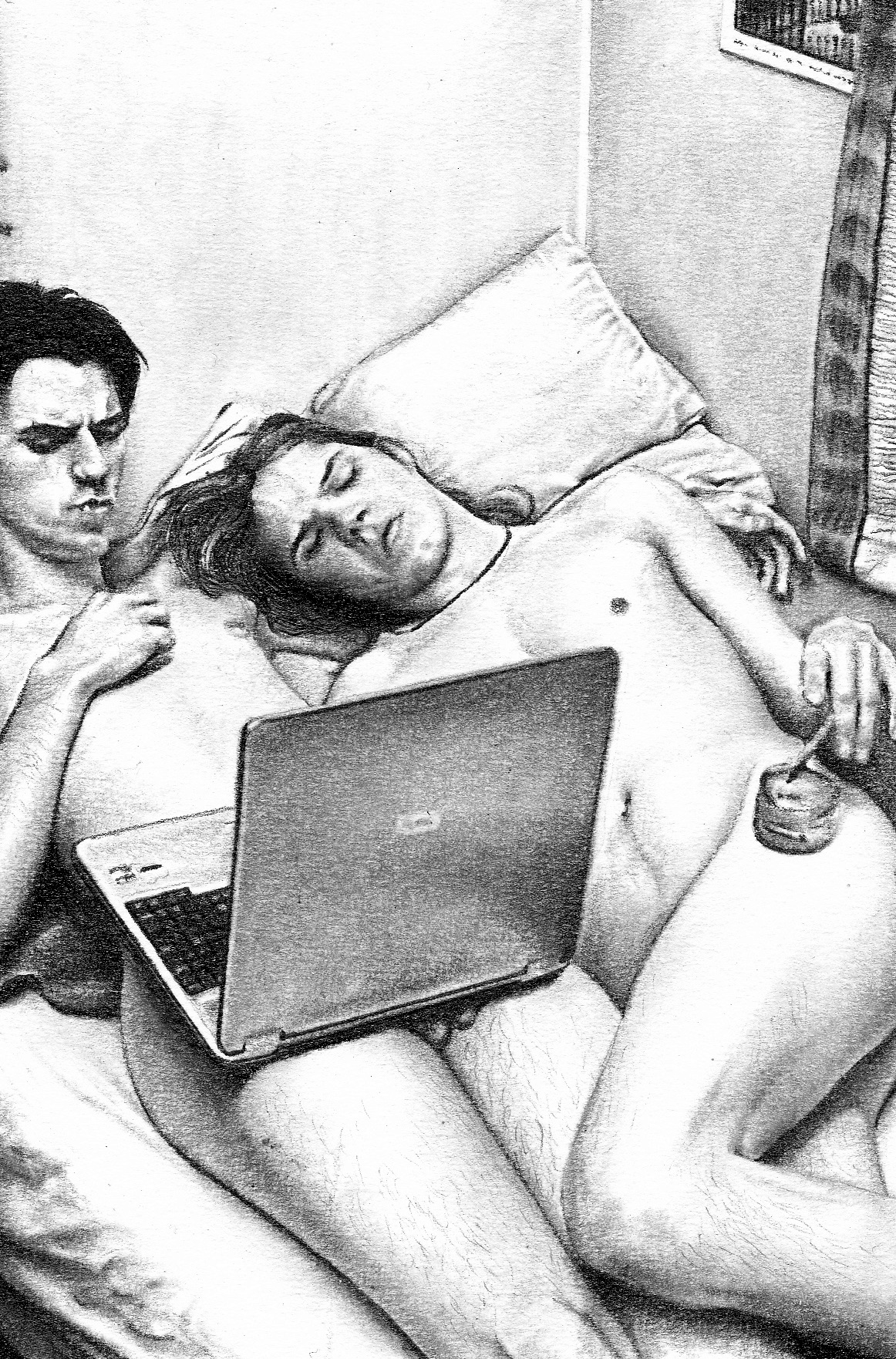

Definitely. For a long time there was so much anger behind everything that my body was experiencing and is still experiencing. I felt really inclined to create pieces where I was basically just telling the audience that they had to sit there and endure what I was going to show them and that it was going to be really uncomfortable for both of us, for everyone involved. They just had to shut up and take it basically. Most of my first video and performance pieces were so tangibly violent. Not only violence against my own body, but I was also bringing in archival footage of surgeries and these really grotesque sort of things that are unquestionably difficult for some people to watch. There was even a particular performance piece where I burried myself under scalpels that I ended up catching a lot of slack for.

You talk a lot about being monitored and probed. How does the gaze, medical or otherwise, affect your work?

Yeah, the medical gaze is interesting because I have so little distance from it, regardless of how truly critical I am. I'll be making a piece tapping into the emotional anguish of hospitalization and then, boom, I'll be hospitalized the next day and I'll lose two weeks in the hospital. I'll come out and I'll go back to that piece and I'll be like, no, no, no, it's all wrong. I have to completely redo this. There's a collapse of the boundaries between my bodily autonomy and the medical complex, so there's practically no way to exist right now in the United States with a life threatening degenerative illness in a way that you are not absolutely trapped under the thumb of doctors and big pharma. I'm still learning every day the ways in which not only am I being surveilled, but that I'm surveilling myself and that people in my life are surveilling me.

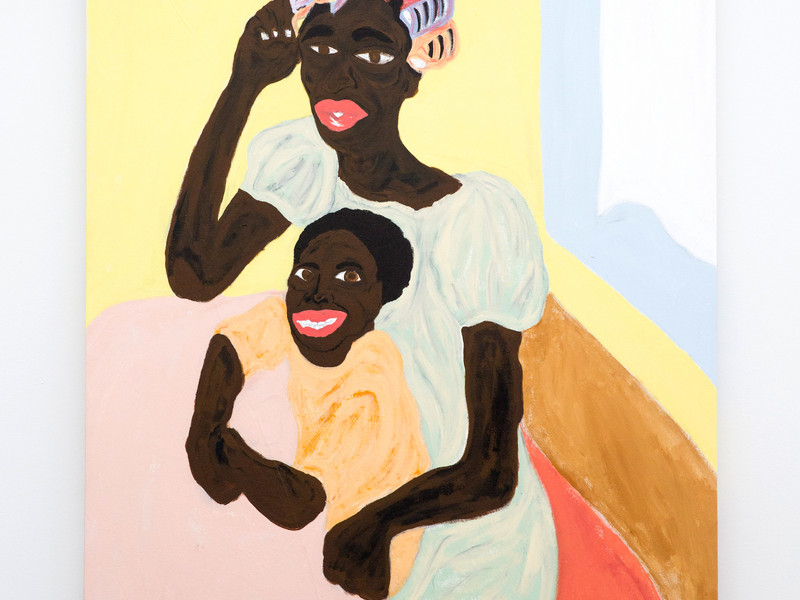

There’s a proliferation of the term ‘body’ in the art world— ‘black bodies,’ ‘disabled bodies,’ ‘queer bodies,’ etc. What is your relationship to the term? Is it dehumanizing?

I think that we are so comfortable with using the word body when talking about blackness, queerness, transness, all these things, because to objectify the other is also written into our language super conveniently. When I say “body” I am fully referring to my body as a proper noun, like an object. There is no purpose in denying the fact that there is such an immense amount of objectification that my body is going through. I always have to capitalize The Body because it's something that I'm observing and collecting data from. It’s so much more than just being inside of it.

I understand that with your condition, you have a shortened life expectancy. How does that awareness affect your work?

Since I was about 5, I was first made aware of the fact that I would be dying young, so growing up in the medical complex has removed any rose-tint about the matter. In a lot of cases, especially when my health is the worst, death is a comfort. There's nothing more comforting to me than the finality of life. I’ve medically died and been resuscitated roughly 5 times now. So “recovery” or resuscitation is such a nuanced concept, because dying was such an innately peaceful experience that I don’t want to return to my body when it happens.

Are you comfortable talking about your experience dying?

Yeah totally. Again, I’m pretty detached about death, but essentially they overdosed me on painkillers just trying to treat my pain. They just titrate it too high and then all of a sudden I'm code blue. My heart is stopped. It's like there is nothing, every time it has happened. It’s so hard to articulate the feeling of literally being brought back into a body that is so hostile and just wishing that you didn't have to be.

So what place does death occupy for you in your life?

My relationship to death now is so tied to other people, it's not even about me at all. Death is about my father—the thought of my father outliving me makes me so sad because I know that that would devastate him. And so when I end up talking about death, it's always like a conversation about love. It sounds saccharine. But it's like that. It's true. It’s true.

You’ve talked about the separation you experience of the mind and the body. According to your belief system, where that does that leave the soul?

As I've gotten older I've had to reconcile that gap between body, mind and soul. For me, it's the hyper evolved part of the human mind that is so lost in its vast consciousness. That is what the soul is to me. It's that space, that cavern between body and mind where I have to be just to like survive the pain to survive it every day. The concept of the soul ties so much into the holistic thought process that I had to develop around pain just to survive it. It's a place down. Very, very, very, very down. That's where it exists for me. I wouldn’t use the word soul, but it's that's where real consciousness is.

Just to close, do you have any upcoming shows or projects we should keep an eye out for?

Yes! I have a solo show at the Barnsdale Museum here in LA in February. It's going to debut first digitally, then half way through the show it'll open physically at a limited capacity.

Thank you for your time. This was a fascinating interview.

Thank you, I really enjoyed this conversation. I appreciate being able to talk about these topics with someone I trust.