While the Earth Sleeps We Travel, and Other Dreams

Ahmed was one of the first speakers to take the stage, and he was greeted with a roar of applause from my peers. His ease in front of this audience was a marvel to me. He told us, with a full-faced smile, that he was a former Iraqi refugee, and I began to forget where I was. My hope to see some punk bohemian deliver platitudes about society faded. This was the first time I had ever seen a young person that looks like me perform poetry.

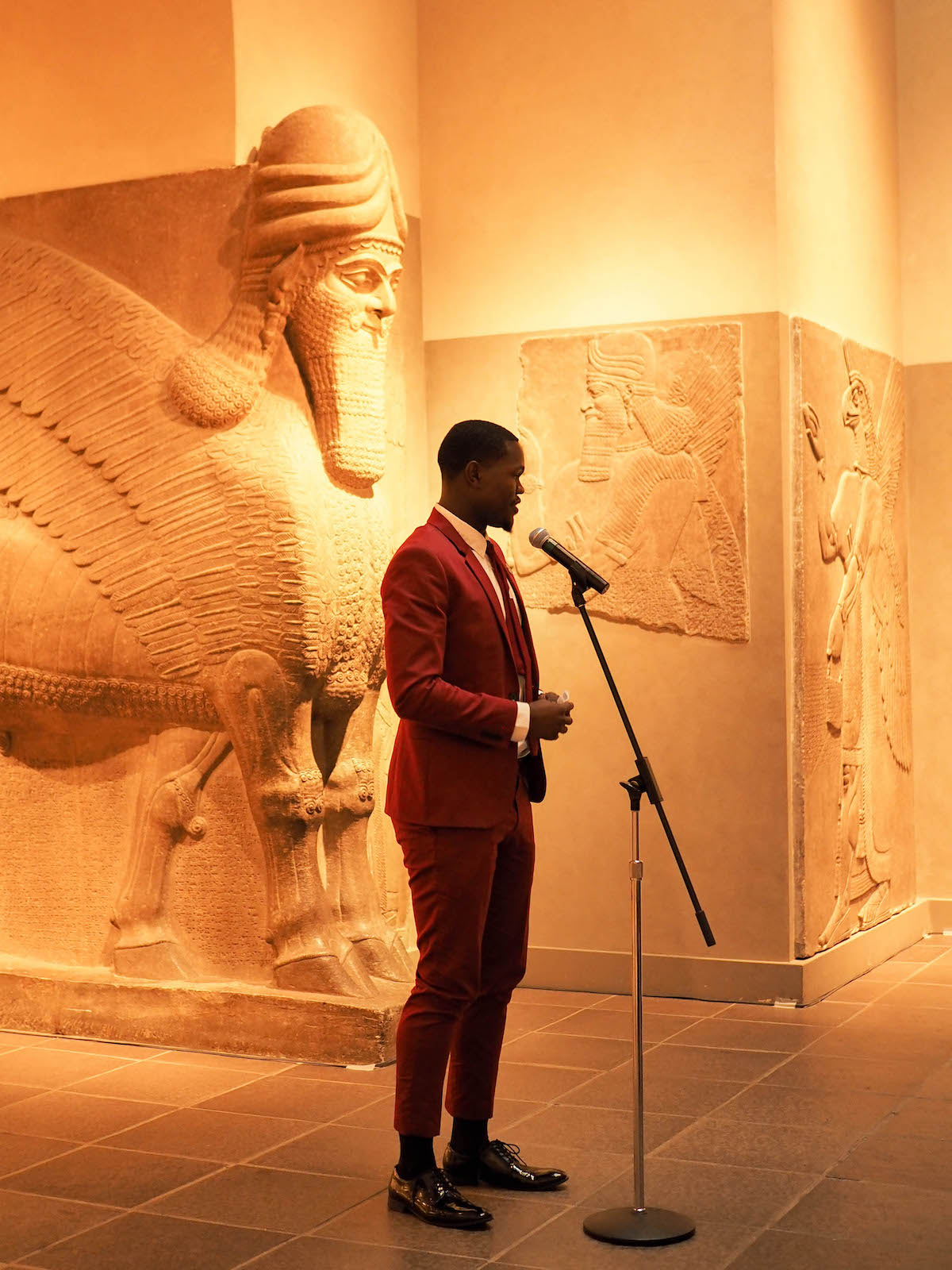

He began to recite his poem, “A Thank-You Letter From the Bomb That Visited My Home,” and I must have been the only person that laughed when I heard the title. There’s something uniquely Middle Eastern in the way he spoke about a bomb, of all things, with an attitude of welcome, both in its wry irony and its essence that friendliness is baked into the culture. The layers, even in the title, amazed me. The poem was powerful, moving, entertaining, and startling in its careful honesty. No one was jumping up and screaming; everyone was motionless, silent, worried that you could miss the next word if you weren’t paying attention. When it was over, the crowd erupted with applause, and the joy both in his face and ours was the same one. Ahmed had achieved at that moment something all writers work their entire lives to get: a uniform experience of ecstasy in art between the creator and the audience. It was in tune with the sort of person Ahmed is, one that has already accomplished in his twenty-two years things that take lifetimes.

Two years after Ahmed recited “A Thank-You Letter From the Bomb That Visited My Home” in that damp basement our freshman year, he would perform it as a United Nations Youth Leader. In the meantime, he was spending his free time between his classes at Wesleyan creating platforms for other refugees through his platform for young creatives around the world, Narratio. Additionally, as if he wasn’t a full-time college student, he was hosting Resettled Podcast on an NPR affiliate station, curating an art installation “Unpacked: Refugee Baggage” with Syrian architect Mohamad Hafez, touring in galleries across the U.S., and organizing writing projects around the world for displaced youths.

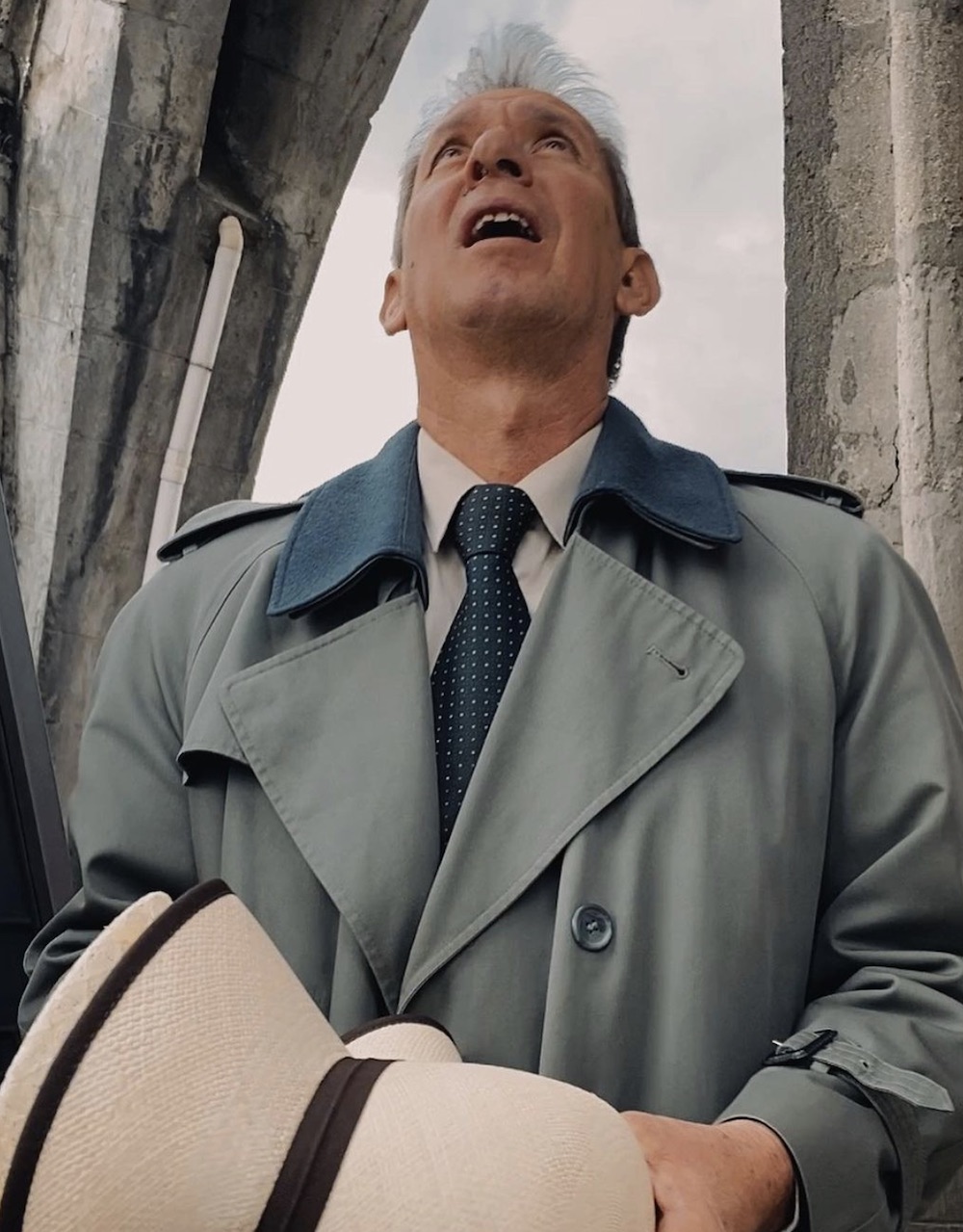

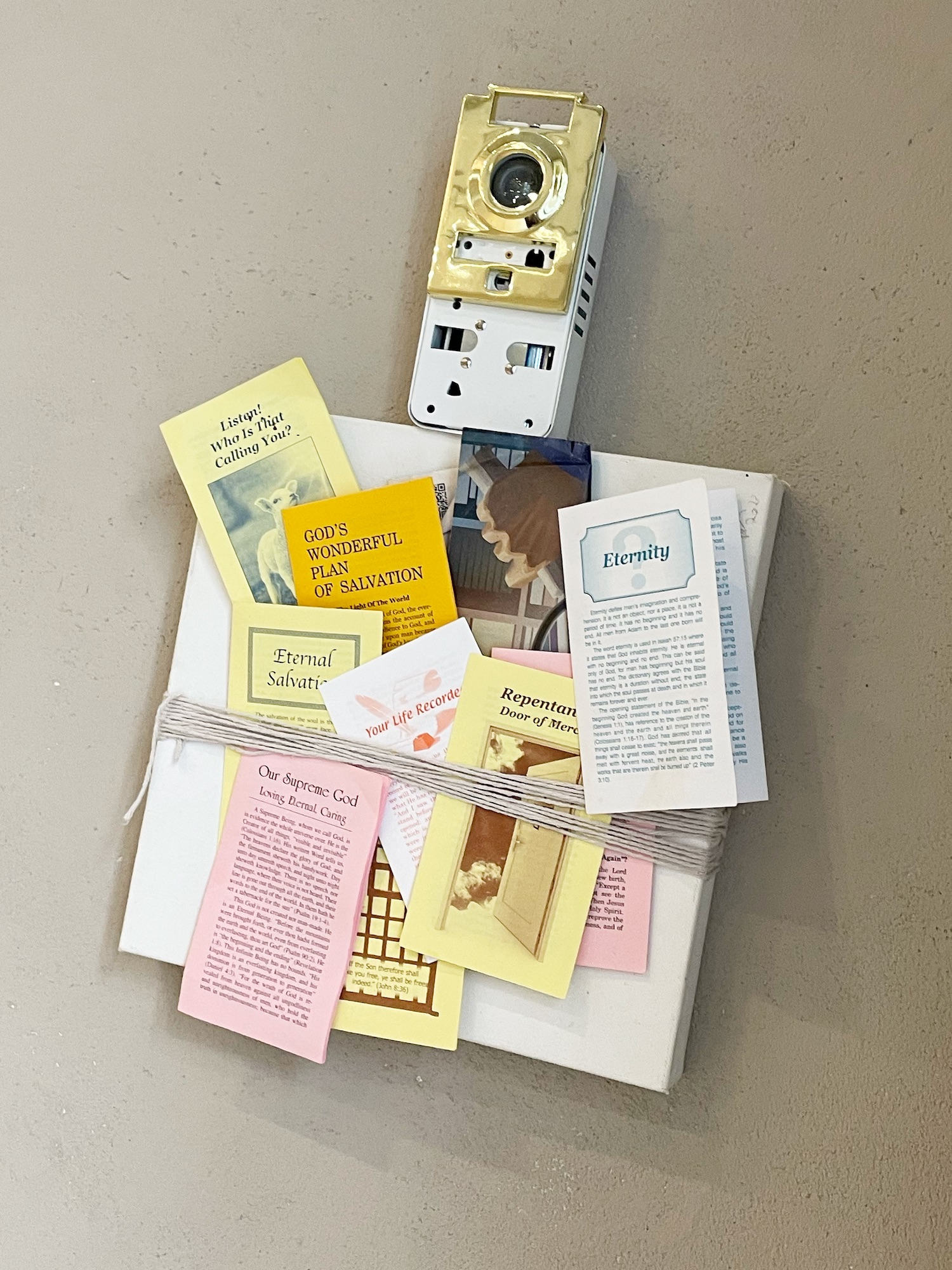

Left — Eid Ahmed, Narratio Fellow

Right — Istarlin Dafe, Narratio Fellow

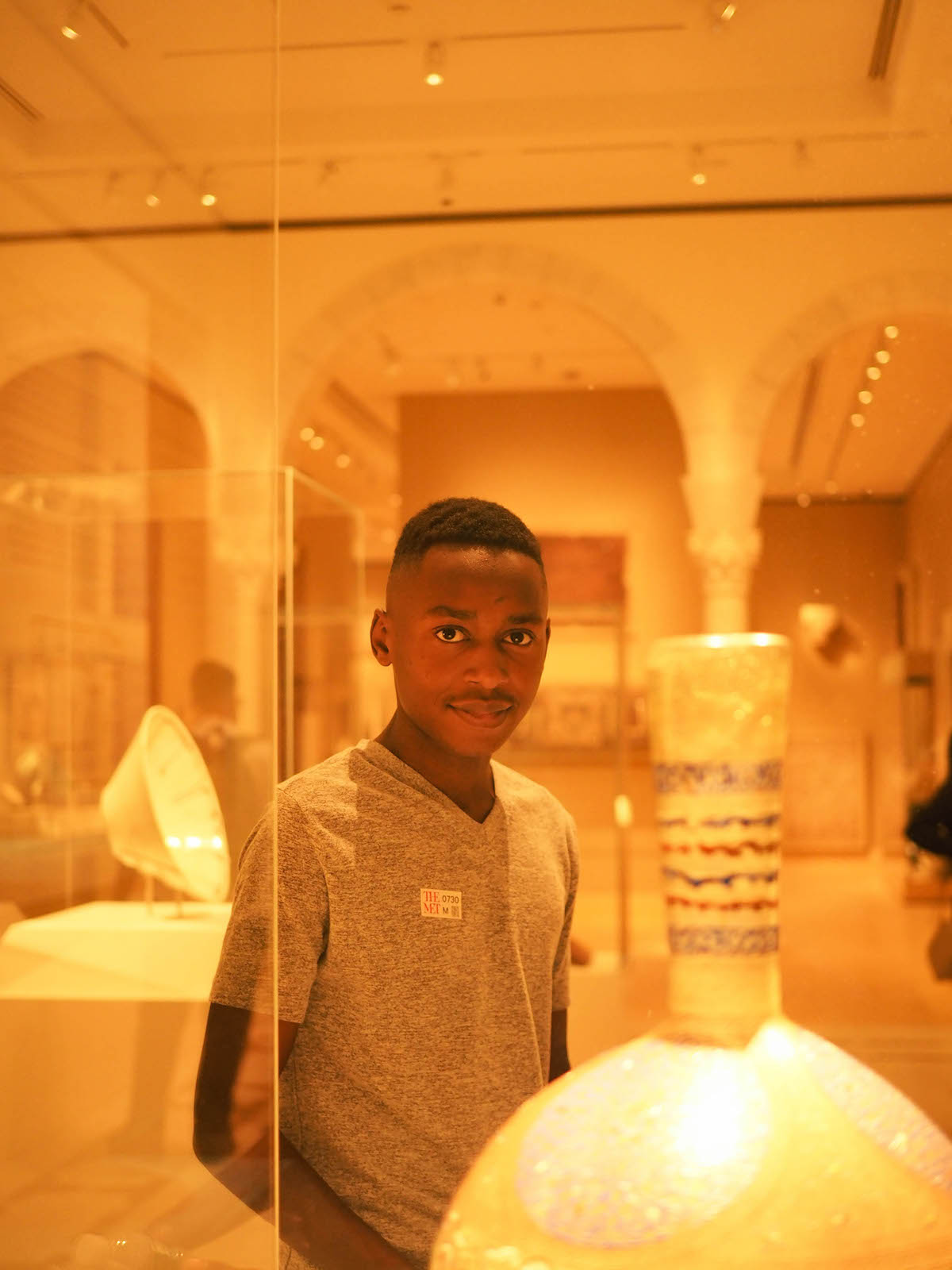

All of this work began to focalize in the last couple of years as he began a book project, a collection of works by Ahmed and other young people he befriended in his workshops across the world. Many of the pieces for the project were created during the Narratio Fellowship, a collaboration between Narratio, Syracuse University, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York that concluded with performances at the MET, Christie's New York, and the UN.

On Monday, October 13th, Ahmed’s first book, While the Earth Sleeps We Travel: Stories, Poetry, and Art from Young Refugees Around the World, will arrive in bookstores across the country. It is already the #1 new release in Middle Eastern Poetry on Amazon before its debut. I had the privilege of reading the book and in Ahmed-fashion, I have never read a book of its nature. Quite like the first work I saw by Ahmed, it left me emotional, shaken, and filled with a serene sense of ecstasy that such a work exists at all. Such a collection of works is a testament not only to Ahmed’s dedication to his practice of storytelling but also to the infinite possibilities involved when honestly and responsibly depicting the stories of displaced people in place of the media’s usual tendency to “objectively” display displaced people as a geopolitical monolith. The book, even without the beautiful stories and works included, is an achievement, nothing less.

After my first encounter with Ahmed at the poetry reading our freshman year, we became friends and staged the same sort of hours-long, superfluous conversations about politics, art, spirituality, and love that my parents have told me are daily occurrences between friends at cafés across the Middle East. The last time we spoke was shortly before Wesleyan was closed two months before our graduation, and I worried that Ahmed and I would not get the chance to see each other again before we were off on whatever came after college. Thankfully, some alternative version of that conversation materialized two weeks ago when he talked to me about his book and the love and hard work that went into it over Zoom from his home in Houston.

It’s so nice to see you, my friend. How are you? How's life?

Lots of crazy days, all over the place, but all is well here in Houston. I'm settling finally into the Texan groove.

What’s the Texan groove?

I don’t know! I guess just physically being in Texas [laughs].

I'm so psyched to talk to you. I've read through the book. I think it's so great.

Thanks again for taking a look at it, really.

Of course. There aren't many books like that, you know? Isn’t that what they always say? If there’s a book you want to read but it doesn’t exist you should write it? And that’s this book! What was the curation process like? How did you go about choosing the people that were included?

That part was a bit easier, the actual collection of the work. I went to Greece, spent some time in Greece, then Trinidad and Tobago, and then across the U.S., mostly spent time in Syracuse. And for the Greece portion and Trinidad portion were just from workshops that I had been doing for the past few years and then the Syracuse portion features our Narratio fellows. So logistically speaking it was collected over a year or so. And once I had it all together, it was as simple as like, ‘Okay, well let's scan everything and make it’s in one place. And I did that at Wesleyan [laughs]. I had this big green folder. I went to like a print shop, got the biggest folder I could find. And basically, the whole book was just in there as individual parts. And it took another year to figure out the structure and finally crack it. Initially, I wrote the proposal for the book and then it evolved throughout. And I appreciated the publisher and editor for giving me the space to figure it out. There were so many things we had to try out. So many mediums we had to figure out. And also we had to try and figure out, ‘Okay, well, how do I come to terms with my positionality. I'm kind of the author, I'm the curator, I'm the editor. I have a connection to it. Every single piece represented. It's not just an anthology.

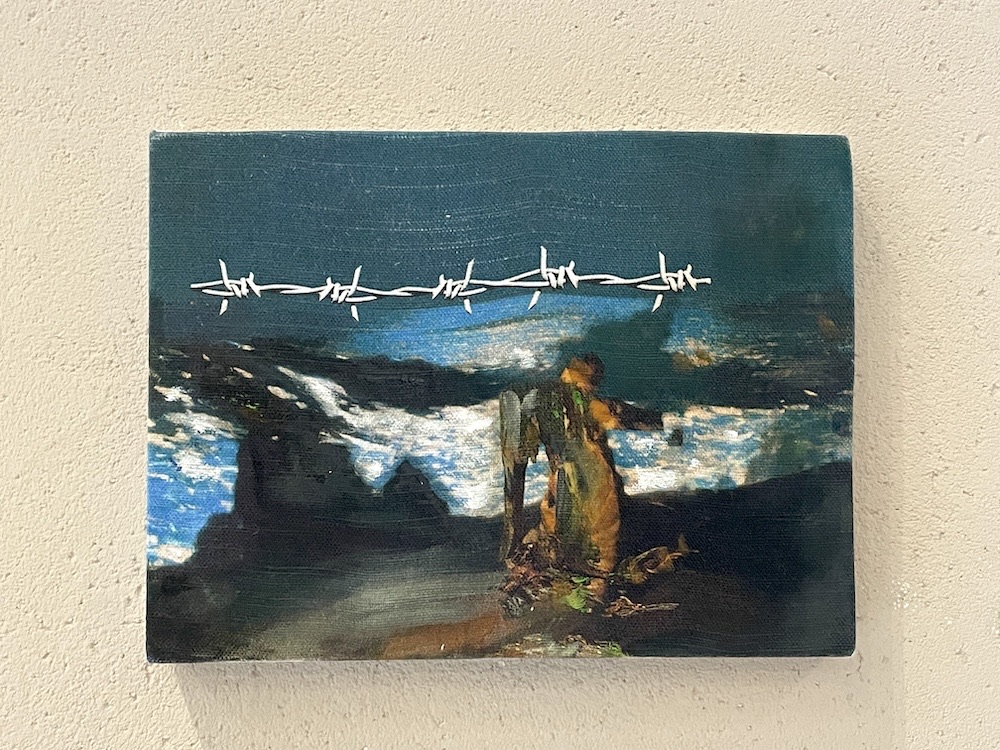

Left — Abshir Habseme, Narratio Fellow

Right — Nurallah Alawsaj, Narratio Fellow

And we know how anthologies of this nature can be so glad it didn’t turn out that way.

I had to recognize the responsibility I have to honor every kind of expression in there, whether it was a, you know, a drawing by a five, six-year-old, or a painting by a twenty-five-year-old, and everything in between. I wanted to present them in a way that felt true to what that individual was trying to express and still have them be able to stand on their own, but also as part of this kind of collective. We went back and forth on how to exactly do that and then eventually settled on the format that we ended up using with my works spread throughout and having these very short introductions before each piece with the hope that my voice and my work would be a mediating force between all of them and bring it all together as a collective. Hopefully, we achieved that.

Could you get into more of what you were doing in Greece and Trinidad and Tobago and Syracuse?

So the book was the focus of that first trip to Greece. And initially, I said, ‘I'm going to go to Greece. I'm going to go to Germany. I'm going to go to Sweden. And I'm going to do these workshops that I've been doing for the past few years, and then whatever comes from those workshops, we'll put the book together.’

And then after like a week or two in Greece, I was like, ‘Oh my God, I need to be here for much longer.’ I had three weeks slated to be there and then I ended up staying for four months. And I was like, ‘Okay, well, depth is more important here where you can meet people in Greece from all over the world.’ Fortunately, Greece has folks that have been displaced from so many different other places and so I just realized, ‘Okay, well, this is the place where I can get the main sources for the book.’ And also just meet people where they're at and be able to engage with them over some time, rather than just do a one-off workshop and then leave.

I wanted this to be different from any other storytelling that's happened around displacement. And what so often happens is that the displaced folks rarely go back to work with other displaced folks or folks that have had experiences of displacement in the past. Obviously, with my family, it's been a few years, but when I went back to Greece and met with folks, you know, for some folks it’s much more immediate, displacement is something that you're experiencing. And in Syracuse, everyone was resettled already and had been in the U.S. for a few years. So that resettled, non-resettled dichotomy was also very interesting. I don't think it necessarily influenced how the book turned out, but it's in there for sure.

So it started by trying to meet folks. I had friends of friends that were in Greece that were connected with different communities and I wanted to set out and run these workshops and do these interviews with the hope of talking to folks about their relationship to how they see themselves and then their relationship to how the world sees them but from their perspective. So that was the guiding question through the workshop, ‘How do you want to define yourself and how do you want to introduce yourself to the world?’ Dealing with these respective mediums, whether it was a painter or a poet or a storyteller, or simply someone that was in the workshop and decided to fill out the template we're working with. You meet folks where they are, and then invite them to express themselves in whatever way that they feel is authentic to them. And that’s powerful.

I'm very curious to know the initial talk that went down when you approached the publisher with the pitch.

I feel like the idea for the book has been bouncing around for a few years. Discussions first started in 2016, and then the publisher said, ‘Let’s do it’ in 2018. And then that summer, the research for it started. They were very supportive. I had a meeting with them in the beginning just laying out, not just the pitch and the story, but also my connection to it and why I was the person to do this now, was kind of a key component of that. And I want it to be upfront about what my role would be here and not make any assumptions about the folks that I would be working with, but to kind of have it be open-ended.

You mentioned earlier, the thought process behind your subjectivity to the source material and your positionality as both an editor and writer in this collection. How did it feel? ‘Cause, we'll get into this, but these stories are deep and very personal to these people. These are the stories that are forgotten, the stories that are hard to collect in the first place. What were you going through internally as you collected and curated them, especially as someone from your background?

It was incredible, man. It was such a privilege. I think, meeting. you know, whether it's within a camp or outside of a camp, you know, being able to travel and meet folks again and be able to, not claim to understand exactly what they're going through, but to still be able to share that. We had at least something in common, you know, and, and the displacement was just a part of our collective stories rather than the entire story. So that's kind of the theoretical answer, but also it was just meeting, it's meeting new people and getting along and making friends. That's another thing I think is such a privilege with this project is being able to connect with folks and to be able to honor their perspective and their own stories and in this physical way, through the book. But also we don't just talk about the book, we don't just talk about this stuff. You meet really powerful and incredible human beings. It was such a privilege to be able to connect with them and to be able to share my own story with them and stand and hold space for one another.

But also it wasn't always like that. It was sometimes hard too. It was very intense and I didn't give myself space to necessarily always process that intensity until way after I came back to the States. I was so engaged.

But there were moments throughout where I had to grapple with my privilege and think, ‘Okay, well, I'm doing this workshop and this camp and by the end of today, I'm going to go back to the apartment that I'm renting. You know what I mean?’ And to sit there and have those separations face you every single time you go and come back, was something that I feel I'm honestly still processing. Whenever I had those kinds of feelings, I tried to always go back to the book and remember that like, ‘Okay, this is what you're trying to do. And hopefully, you're honoring these expressions in these humans through this project.’ But that doesn't make that discomfort any easier per se. But, you know, I try to just go back and just continue focusing on making sure that these folks are appreciated and that they feel appreciated, that this project helpfully serves them. In a way that is, authentic and powerful.

Beautiful. I’m very curious, for someone like yourself, an Iraqi refugee, what does it feel to you to be able to go and do this work? I feel at this age, for many of us, in our early twenties, we tend to look back at who we were when we were like, twelve, and think about how our twelve-year-old selves would see us today. Do you feel like you're satisfying something within yourself? You’re having, not a return, but a revolution in yourself?

I don't know if I would say it's a revolution with myself per se, but I think it's something that I find deeply inspiring. A question I've always thought about is, ‘How are my own experience and my story creating other spaces for other stories to exist side by side and beyond it.’ And I think this project is a way of concretely doing that. And in a way that is the most personal thing I have ever been able to do. Because back in high school and early college, I felt I had the privilege of sharing my story with so many amazing humans, but I thought, ‘Okay, well, I want to make sure that the story is always connected to the work and a larger mission of trying to amplify and work with stories of those that happen to be displaced, not necessarily stories of displacement, just stories of those who happened to be displaced.’ And so this book was a way of trying to present that through all of these different, amazing individuals. Even though the process of collecting the stories and the different expressions, there were moments where, in a meeting with someone or I was doing a workshop, connecting with folks, having very personal conversations, I felt familiar. There was a familiarity already there. And personally, growing up here in the States, I haven't had access to too many folks that speak Arabic my age, besides my family of course.

And so to be in a place where I can just speak Arabic for an entire day or a couple of days was something that I hadn't experienced for a long time and, In a way, it just like made me feel so appreciative of the whole experience, but, it allowed me to engage deeper. And, as an Iraqi and an American, these are things that feel are sometimes competing. Through this project, I feel like I got to work with both and in ways that are productive and also engage with the absurdity of both sometimes. I'll never forget the first time I was preparing to do a workshop in a camp. A Syrian man came up to me and started speaking in English and was speaking to someone who was my boss at the time in English. And then all of a sudden I switched to Iraqi Arabic and he was like, ‘What is this?!’ And for a moment, he couldn’t fathom that these two things can be in one person, you know? I spent many weeks there and got to know everyone, but it's kind of small moments like that where your duality is facing you. And you're like, ‘Oh yeah, my Arabic might not be as good as it used to be, but it’s still there and we're still able to connect them and communicate in that way. This project in a way unlocked all of those experiences.

You mentioned earlier that you weren’t trying to find ‘refugee stories’ but stories of refugees and how do you navigate that? How do you go about making sure that within the workshops or even within your work, you aren't pandering to some sort of like Western appetite for these sorts of stories?

Absolutely. I think it just comes down to telling the full story. Oftentimes when we hear of stories of refugees, it's just about why they left home and that's kind of where it ends. It's the story of tragedy. And what I think I mean by that phrase, ‘Stories of displaced folks rather than displaced stories,’ it's to tell the fullest extent of that story and to meet people where they're at and ask them and give them the option to represent themselves in whatever way they want to.

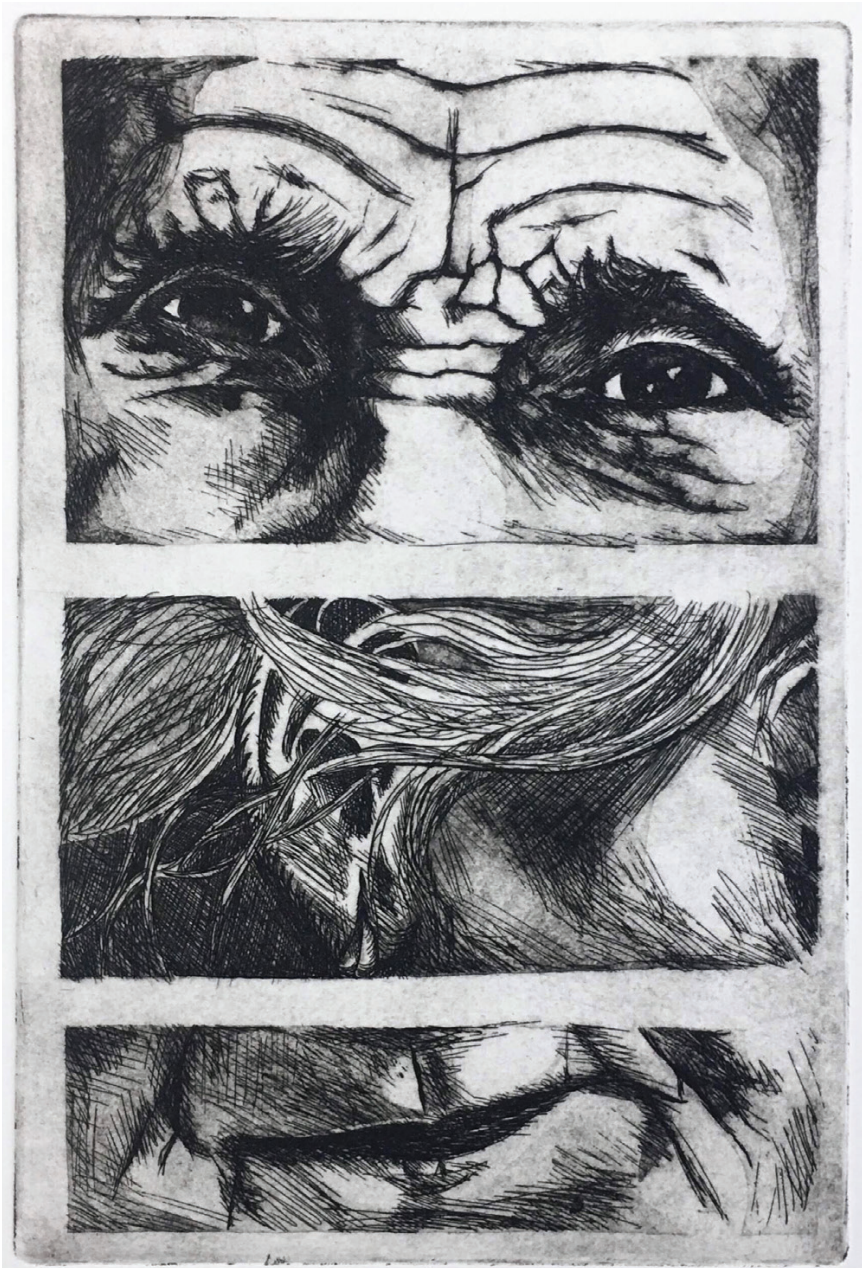

For example, the Narratio fellows whose poems are all featured in there. The program was focused on poetry and all of their poems that were featured were rewriting labels of objects in the Ancient Near East Gallery at the MET. Some of them address displacement in some way, shape, or form, but most of them don't. So it’s not necessarily a story of displacement, but a story of someone who has experienced displacement in the past. So I think it's just embracing the fullest extent of someone's story and not having it start and end with tragedy.

A question I grapple with myself a lot as a journalist that I think all journalists should never stop asking is around representation and who is best suited to speak on what issues, and it’s something I think about a lot with your work. You’re telling stories from the point of view of someone that's experienced the subject. I'm curious to know your thoughts on representation. How do you feel about people who have not experienced displacement, or no one close to them has experienced displacement, writing about displacement, or writing stories of displacement? And what can be done to make representing these stories more accurate?

I'm not saying that everyone who writes about displacement or shares stories of displacement has to have experienced it or have been surrounded by it. I think that adds a different layer to that story or to whatever kind of you're trying to produce. But I think for folks that are writing about displacement we have to make that distinction. Are you writing about a so-called a ‘crisis,’ so-called? Are you saying there's a refugee crisis and this is one of the stories of someone who is experiencing it? Or are you saying, this is the story of someone who happened to be in this place at this time, at this moment, in this context who is experiencing displacement?

So at first, I think we have to be clear about the parameters. But ultimately, again, it goes back to honoring that person's experience to the fullest extent that they feel comfortable in. You have to be clear about your parameters, but you have to again, meet that person where they're at and what they want to express. And be honest. Make sure that that person knows what they're signing up for and where their story will go and where their story would travel. They could be the central guide, if not the teller, of how the stories are represented. Through the stories in the book, you know, most of the interviews, I edited them for clarity, but I tried to preserve that person's voice as much as possible. It wasn't just me digesting what they told me and then putting it together. It was directly saying what they said. And then be clear about your positionality to the story as well. It's not an easy job, but I think these are all things that will make the job easier.

Something I was wondering about, you know, none of the people whose stories you’re telling come from the west, and a lot of them don’t even currently live in the States. How do you feel presenting these stories to a western audience through a western publisher? How do you feel about your audience? What’s your relationship to it?

That’s a great question. I mean, the audience is key, and first of all, I want the book to be accessible to multiple audiences. But first and foremost, the audience of most priority is the folks that are represented in it. I hope that I've made them proud through how this is represented, or have the book has come out. Beyond that, I think ultimately I want it to be an educational tool and hopefully, something that inspires you, I don't want it to be the kind of the end all be all. But the audiences that I want to reach are varied. I want to reach educational institutions. I want to reach folks that have maybe never related or have never heard a story of someone who has been displaced. But also because of the multimodal nature of the work, I hope that it presents this three-dimensional view or expression of the complexity of individuals who are artists, are poets, are storytellers, who are, in this case, united by this experience of displacement.

But also I hope that it becomes clear that there is no universal experience of displacement either and beyond that there's no universal expression of displacement.

There was something I read in the book, something beautiful the Iranian guy in Greece named Erwin said, ‘Everywhere you go, the sky is the same.’ And it made me think, ‘What was the aim of this book? At least in the initial process of curation. Was it to portray a common experience of displaced people or were you aiming to show that displaced youths are a part of a greater community of creative youths regardless of their displacement. Or maybe you’re dealing with a little of both.

I don’t know. When we were making it I didn't want to come out and say, ‘Okay, well, this is what you should think and this is what you shouldn't think.’ I wanted folks to speak for themselves and express themselves in all these different ways. But I think ultimately it's a call to action to create spaces and create the potential for the creative expression of displaced young people to be amplified in global ways, in ways that are on par with the art and poetry and stories of those that aren't displaced or haven’t experienced displacement.

I think part of it is to create this three dimensional and very complicated expression of what someone who has experienced displacement is going through. Also in what they want to say to the world on their terms, and then beyond that to just meet folks through their kind of expression and not necessarily think of that expression as any lesser than folks who haven't experienced this placement. It’s an effort at kind of equalizing access to that creative expression as well. And making sure that folks feel, you know, first and foremost, comfortable in what they're trying to express, but also in sharing that in a way that's hopefully thoughtful and engaging and accessible.

You mentioned this earlier, but I wanted to know about the process behind including your work in the book. There are all of these beautiful, heartbreaking, and raw and hard to process stories throughout the book and it very much felt like your works sprinkled throughout were sort of a guide for the reader across the eclectic experiences presented. You have such a style and you’re a beautiful writer and having your work interspersed between it felt like I was with you finding these stories.

I’m so happy that that's what you got from it. I'm glad that it's a mediating force. It took a couple of tries, a couple of drafts to try and figure out, ‘Okay, well, do we want to put everything in sections? This is the poetry section. This is the photography section. This is the story section.’ And then where does my work fit into it? I was like, ‘Should I even include any of my own work? Is that necessary in this case?’ So it was just a lot of trial and error and ultimately again, trial and error with this idea in mind that all of these works have to be in harmony with one another, ideally in a perfect world, but also could stand on their own as these individual pieces. So that was a key consideration throughout. Like, does your own work add to that harmony or does it take away from it? I wanted to make sure that the former is the case. I'm not just stepping in for the sake of stepping in.

I was wondering as well how your work with Narratio and the Resettled podcast and all the other work you do influence your process with this book. Did you feel your relationship with the book changed as your other projects progressed? How did those projects help your growth as an artist and a curator?

It's a great question. I think it was the growth of Narratio’s work but ultimately was completely independent of it. A lot of the workshops that I did are drawn from my experience from the Narratio projects we conducted. I was doing these one-off workshops over a couple of years and the Narratio Fellowship was born a year after I went to Greece. And I thought, ‘Okay, let's create a program specifically for displaced young people where we could work together for at least a month and work on these expressions.’ And I thought, ‘I know what it's like to a one-off workshop. What about a program? How would that shift the expression? What kind of spaces can we cultivate over time?’ I think that's one thing that has stuck with me and I've tried to hold on to and work with and grow from, this constant, constant, constant critical engagement with the work itself and with what I’m able to contribute to it. I think the book and Narratio are complimentary in different ways and I hope that they improve upon each other.

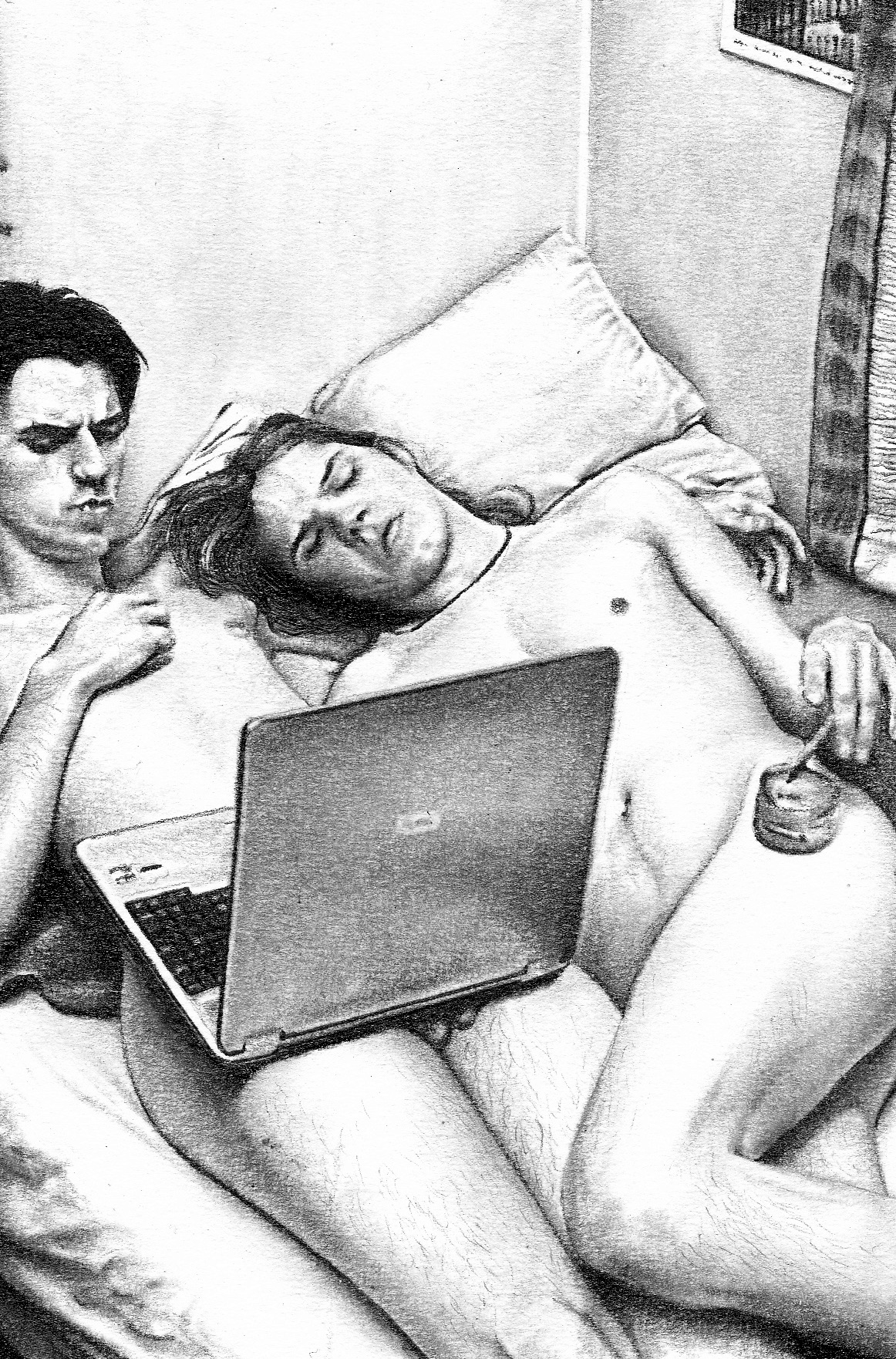

Left — Khadija Mohammed, Narratio Fellow

Right — Ibraheem Abdi, Narratio Fellow

Sometimes I wonder about you, my friend, do you ever just look around and think, ‘Man, I just want to get really into woodworking.’

[Laughs]

You’re so talented but do you ever feel like you are obligated to continue the amazing trajectory you’re on since it started when you were so young? Do you ever wish you could just drop it and try something else out?

Thank you for that question, man. I appreciate it. I think it's something that I try to always take a step back and think about. I do derive so much joy and so much inspiration from the work itself and also it never feels like an obligation. It’s a privilege and it's a responsibility to be able to do the work and to hopefully continue to do it in thoughtful ways. It's something I continue checking in with myself about. It’s coming up now where I’ve graduated from Wesleyan and I have a bit more time now. The work continues and is ramping up in different ways but also, I think, it's a moment now to pause and think about it all. And I think that moment of pause is important for whatever the next stage of the growth of the work is. It’s an honor to be able to do the work and whenever I can, I try to pause and think and reflect and, always ask myself, ‘Am I contributing and helping to bring these projects to new heights?’ And so far so good. So, if that answer ever changes, maybe I'll go into woodworking. We'll see. But in the meantime, I think I'll stick with it.

Something I would like to know, Ahmed, is that, for someone like you that has already accomplished so much, I wonder what it is that you feel like you haven’t done yet. I mean, you’re a UN Youth Leader. What do you dream about? What’s your dream project? Like, ‘Where do you see yourself in five years? Is there anything you feel like you’re still working toward?

I feel like I always try to avoid those scenarios. Because I feel like if I get specific then, for some reason, if that doesn't happen, it's like a sign of failure or something. So I always try to take things as they are. But, honestly, I mean, this book was the dream project. It was a way of physically cataloging the mission. Being able to present it to people. For a long time that was it. I'm curious now to see how it's received, how the world is going to be able to interact with it. and then maybe after that, I'll think about whatever else comes next. But the dream, man, is to be able to do this work. And in a way that is, you know, hopefully, powerful and, and thoughtful, but also systemically, a way that kind of binds and creates new spaces that are worldwide, you know, and I think now Narratio is trying to do that and hopefully we're on the right track. I think ultimately it's the systematic change that we're trying to kind of create by creating spaces where these voices can be amplified and where their power can be activated. Systematic change. That’s the dream. There are many dream projects in the middle and hopefully, we'll get to do those.

Only you, Ahmed, would hear, ‘What’s your dream project?’ And answer, ‘World peace.’