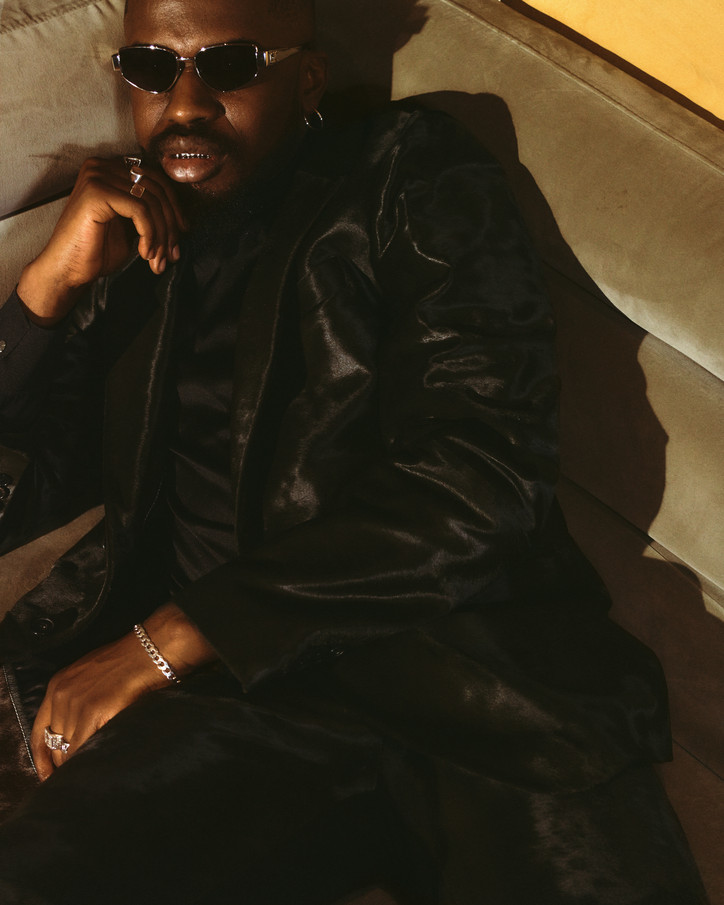

“I Don’t Want to Live a Plastic Life”: nusar3000

Yes, nusar3000 embodies a familiar, yet multi-faceted motif: just let the damn music do the talking. Since he was old enough to count the hairs above his lip, he’s immersed himself in the expansive world of FL Studio, conjuring up self-produced rap songs that predate his eventual ventures into some of the most ethnic genres the world has to offer: baile funk, jazz, salsa, flamenco, kuduro, garage, guaracha, shoegaze. He prides himself on being a sponge to the array of cultures the internet has exposed him to, treating his enigmatic digital footprint as a vessel for passion projects of different kinds, under different names. It wasn’t until the aftermath of the pandemic that he settled on his current moniker, nusar3000 (he says “tres mil” rather than “three thousand,” which sounds a lot cooler), a fittingly cybernetic label for a self-proclaimed internet baby.

nusar giddily speaks on his inspirations and outlines his manifesto as he smokes hash and laughs into the camera while Pelayo acts as his translator. English is a second language to them both, but it’s still so easy to tell that nusar is a genuine admirer of music both as a creator and a consumer. I can picture a 60-year-old version of him still plugging away at FL even if he couldn’t make a living from it. When you listen to “NASKAR,” the lead single to his new album, 3000, it’s like you’ve been thrown into a coliseum with raucous lions. The sound of pitched-up woodwinds, guitar distortion, and frenetic, blood-pumping drums are layered behind nusar’s chipmunked vocals, all while supercar engines and pixelated blips leak onto the canvas. It’s an exhilarating intro to a concise firecracker of a record with major roots in Mediterranean culture. Just days before his second-ever live performance (at Primavera Sound no less), nusar3000 takes me through the earnest intentions and spirited upbringing behind his blossoming career.

Olivier Lafontant— When did you start making music and when did you realize it was gonna be your career?

nusar3000— I started to make music when I was like 12, 13, more or less. I started to write lyrics… and in that era there weren't “type beats,” so I had to produce my own music to be able to compose and record songs. I realized that I can live and I can get money and make a living [from] this like three years ago. I started making rap songs as a kid and then I discovered salsa music because my grandma used to listen to it in the car. And then I discovered psychedelic rock and progressive rock and jazz, and I give [thanks to] this music.

Which artists and which bands were some of your early influences?

nusar3000— Nowadays Death Grips is a big influence. Ariel Pink… hmmm. There’s a music group that is not [that] famous but [they’re called] Strawberry Alarm Clock, it’s like psychedelic jazz rock. Thom Yorke, Fania All-Stars… Machine Girl too.

And do you still write your songs or do you only work on production?

nusar3000— I make everything. Writing lyrics, producing my music, recording my stuff, doing the artwork, and uploading it to Bandcamp.

Pelayo— He probably has like 20 albums on Bandcamp, other names and deep stuff. [nusar3000 laughs]

You mention other names being used, so when did you settle on nusar3000 being your name?

N— That was like three years ago. I had other projects and suddenly I realized that music is the tool I have to express myself and to explore my feelings. I realized that I cannot make music that is based on the rules of the industry––with the intention of [engaging] people. I started making music with another name, nusar3000, because I decided to make music for myself, to myself.

You wear these masks sometimes that kind of remind me of Kanye West on the Yeezus Tour. Everything is very grand, elaborate, and specific. Why do you think it’s important to have strong visuals to go with the music?

N— It’s divided into parts for me. When I mask my face, this is not for a performance. I don’t want people to have an idol that’s [just a guy]. I think that when an artist [presents themselves openly], good feedback or bad feedback can affect the person. And when a person makes bad decisions it can affect the project. I think that all the visuals for me are a way to [present my imagination] and the universe. “NASKAR” [depicts] people who live that life.

Are you familiar with MF DOOM? Is he a source of inspiration?

N— Yeah, for sure. That’s the perfect example: a guy who focused on making music, and he [didn’t] want the fame or the consequences of fame. I want the recognition of the artists I admire. I don’t want the recognition of people in the streets giving me good or bad comments. Burial [doesn’t wear a mask] but the way that [he] managed all his career, I like it. I feel less pressure if I don’t have to expose myself. It's like when I make music and I don't have to think about myself as a person… I [can take] ideas from [anywhere] and [act as] a channel.

Is there a fear that comes with getting famous? Do you feel like this is something you’re gonna do for the rest of your career, separating yourself from the music?

N— It’s more because I appreciate my space. I love [getting] a coffee with my grandma, and going on vacation with my friends, and being hungover in the street coming from a festival. I can be focused on myself. The fame is good, I think, at the beginning when you start to gain self-confidence and when you feel [actualized]. But I think long term, almost every person that gains viral fame [ends up] suffering or with mental issues or anxiety. I wanna be like a surgeon or a doctor. The doctor that does good work gets the recognition of the other doctors that are better than [them]. It’s not [like] a good doctor has people in the streets saying “Wow bro, you did so good on that heart surgery!”

P— We just arrived in Barcelona for Primavera Sound, and when you are backstage with other artists, sometimes people get fake because of the person you are. This way he can be around there and most of the people won’t know he is, so they will treat him in an honest way.

N— I don’t want to live a plastic life.

I was at home playing FIFA the other day as I listened to your upcoming album, 3000, and the amount of different sounds and influences you put together sound like they come from someone who grew up on the internet. How did the internet influence your style of music?

N— I’ve had conversations about music and the internet, and there's a lot of people that say ‘No, music was better before and was purer before.’ But for me, the internet is everything because it's the only way that I [could] connect with music. At home, my parents didn't have hundreds of vinyl records. I discovered music on the internet. And I think that the internet democratized the music. A guy from Bolivia who has no resources to get a guitar and go to a record label can make music with a DAW [and] discover music from Paris. Two weeks ago, I was talking with my father about music and I was thinking to myself like, ‘Wow, thirty years ago you could only discover the music that you could buy.’ If you don’t have a store that takes music from Africa, from Asia, you cannot access this music, so [it] doesn’t exist for you. Nowadays, the internet is my home, my country is the internet. It’s where I’ve spent the majority of my time [spent] alive.

I feel like that makes sense for us who were raised on the internet because like you said, music is so democratized. Now I can listen to rap, and I can listen to a Radiohead song, and then a nusar3000 song right after ‘cause that’s how we grew up.

N— Twenty or thirty years ago, [there were] the heavy metal guys, the rappers, the emos, and the musicians. Nowadays it’s mixed. I have friends that listen to salsa and Detroit rap. I think [putting a price] on the music limits the music and the experience. Sometimes I feel the same sensation when I listen to Mozart [as] when I listen to––

Playboi Carti.

N— [laughs] Playboi Carti!

What was the inspiration for your new album and where did you go to record?

N— The heart and the main source is the Mediterranean sound and the Mediterranean spirit. I am from Spain and [have spent] all my life around the Mediterranean Sea. Ten years ago, I started to listen to music by myself, and I discovered music from Iran, music from Morocco, music from Egypt, from Greece, from Turkey. I realized that this music makes me feel the same [as the folk music] of my country. There is something magical around the Mediterranean Sea. And I’m trying to reinterpret and give a space of importance to the cultural heritage of all these ways of living. And this is mixed in with the different places I’ve been traveling to around the world. I’ve been to Argentina and I connected with the cumbia villera from the more dangerous hoods. And then I went to Portugal and I connected with the guys from Cape Verde and Angola, and they showed me kuduro. Then I go to England and I discovered UK garage, drum-n-bass, jungle. I tried to mix my cultural heritage with my experience going around the world and try to make, for me, what [the internet is]. That is, the mix of everything that we have. It’s far away but we feel so close.

P— Morocco [was also] a big influence for this, so we said ‘Maybe we should go there and stay with people there and record the videos and the sounds —

N— And eat the food that they eat. When we were there, we were in the car going through the desert, listening to the album, and the [driver] who was a 60-year-old guy was like ‘Wow, bro I love this music, what is this?’ And I was like ‘It’s my music!’

I think a big part of your story is that not only do you listen to new music on the internet, but you go to the source of the music. Can you describe the places that you go when you visit a new country to find new music?

N— I want to go to the clubs that are not the mainstream [ones]. For example, when I went to Lisboa, I had Latin friends that were living there and I met Brazilian and Cape Verdean guys… And when I was with them in their homes it’s like, ‘Bro show me the music that you listen to.’ I don’t want the tourist life. I want to go to your bar, with your friends, listen to your music, see the vinyl [you got from] your mom.

I saw recently that you joined Rusia-IDK, the Spanish collective of DJs and producers. How did that happen and how do you feel like you fit in?

N— That was crazy because they are friends of mine and friends of my friends. We used to hang out and we used to share music [we’ve produced]. And Manu, who is the manager, is a good friend too. I respect his work a lot and his vision, and I love the way that these guys are reinterpreting pop music and giving it sauce and personal love. It’s good taste and honest intentions.

How do you feel going into Primavera? What are your emotions like?

N— It’s your first time doing such a big festival. Wow, it’s crazy because it’s like Inside Out. I feel like there are different people pushing buttons like boom, boom, boom. I feel so happy. I feel proud too. It’s an honor for me, being part of it because [there have] been a lot of crazy artists that have been at Primavera Sound. And it’s my second live gig, and the first one was two weeks ago. *laughs*

P— They called us from Primavera like three weeks ago and [at first] we thought that maybe we were not ready for this. But like with everything we've [done so far], we were like ‘Oh fuck it, let's do it.’ It's a great opportunity.

N— I feel so happy and disassociated with it, it’s like what the fuck! It’s like I’m the same day as Arca or Sega Bodega. It’s crazy that people have to choose [at] festivals. You cannot go to everyone so if there are people going to your [set] it’s because these people are deciding to give you this time. For me that’s a pressure that I love.