Art Scene: Detroit

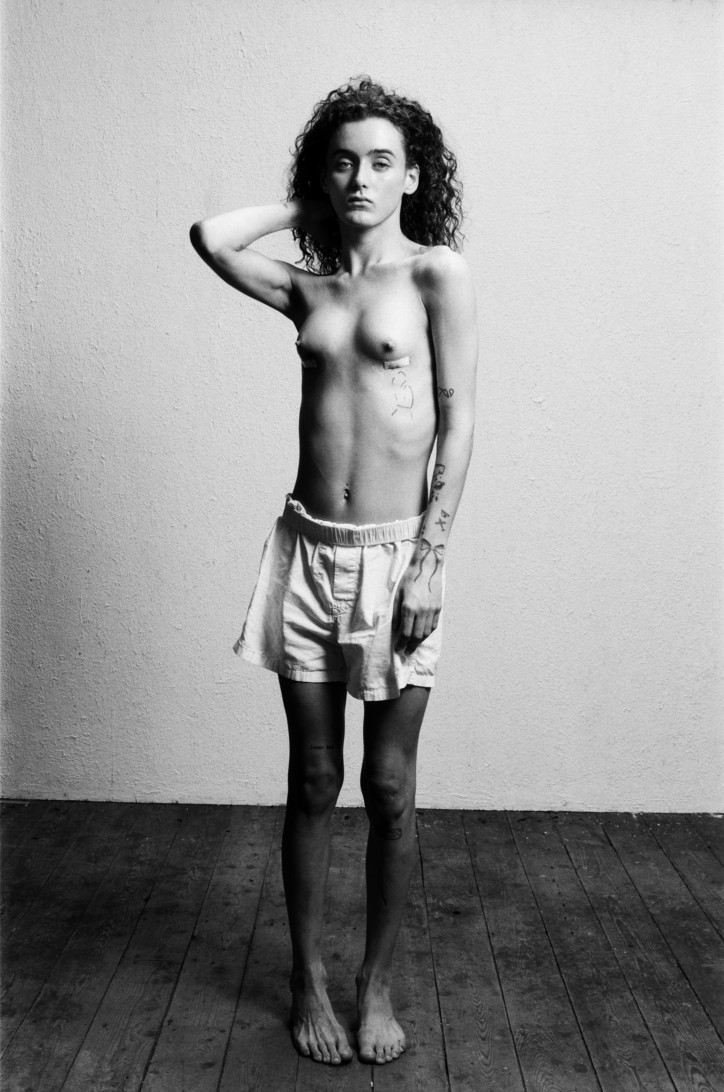

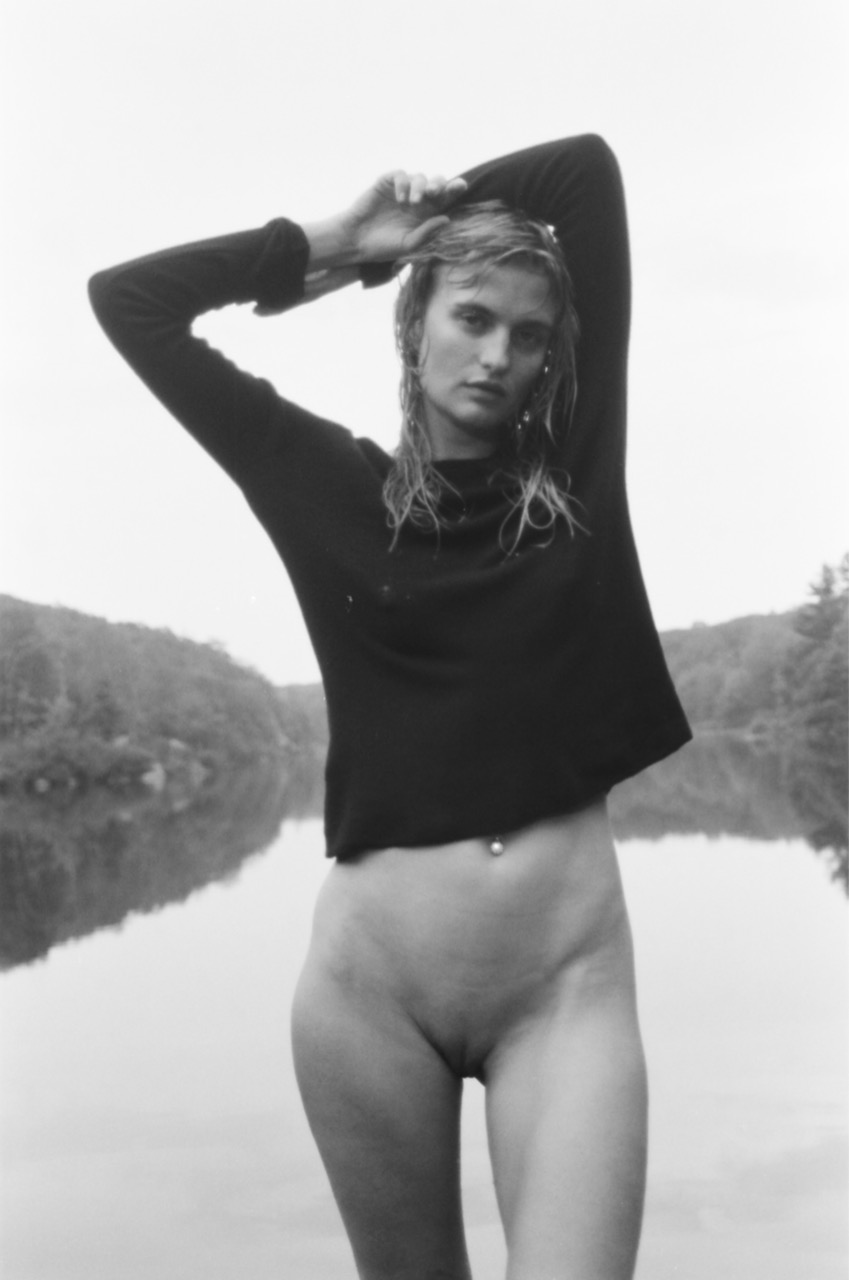

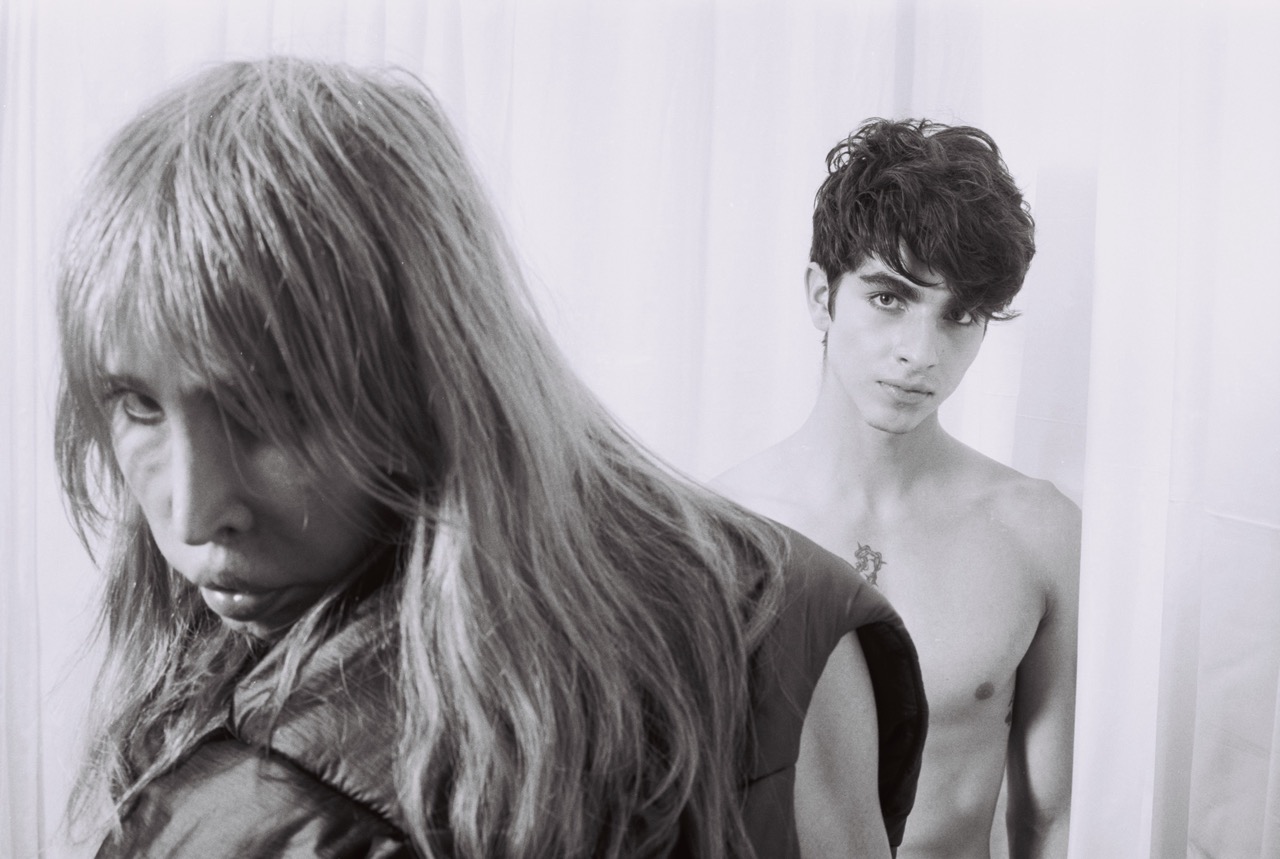

Her hair at the opening was remarkably artful, braids threaded with clear beads from mid-shaft to ends like a heavy Egyptian wig, though I must admit I was happy to admire it from afar. The impulse to touch someone else’s hair is strange and the artist’s use of it in her work fascinating, since it almost confirms and denies that she herself is a living artwork, one that is not to be touched even if the impulse is strong, but who is also by no means an object, and therefore calls out the impulse itself as a subconscious regarding of the black body as a mere object of wonder by a white audience. The neon message, then, is directed at this audience, while nodding to the black viewers that would immediately understand the sentiment.

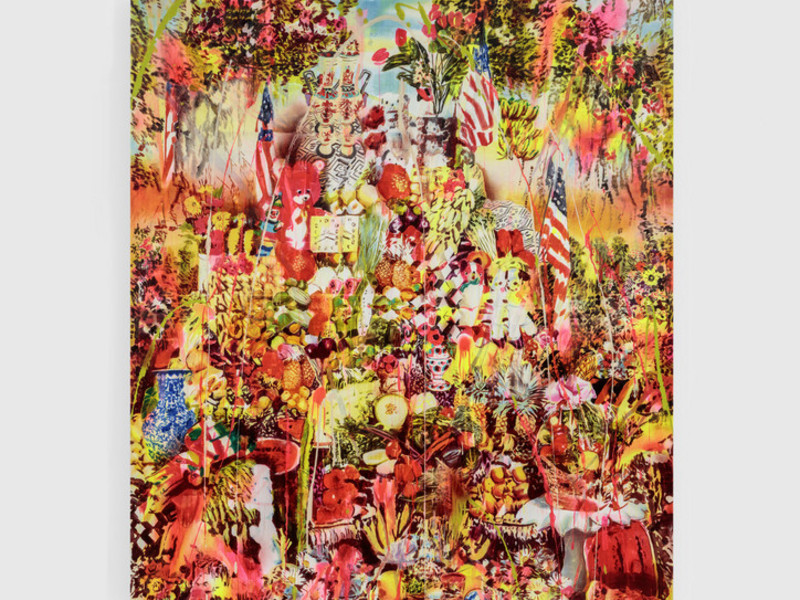

Her other works are about hair as well: one attempts to replicate, in its way, the overwhelming nature of a beauty supply: a wall mounted with false hair pieces, all ombréed from a dark, natural-colored root to a Crayola yellow hue—not blonde, but the cartoon version, a distant reference to Eurocentric standards of beauty (blonde only naturally occurs in the white population), but with an almost childlike interpretation. Apt, since the work across is a set of surrealistically-sized pink berets, exact replicas of those the artist wore in her own childhood—remnants of her first lesson in personal adornment. The neon sign’s brassy imperative can easily refer to the artworks themselves: “The security guards were saying, ‘This is the one to watch, the wall of hair,’ because they know how much black women pay for their hair,” Massey said with a laugh, though all the hair pieces were synthetic, a choice based both on cost and meaning. She confirmed my curiosity that one hair piece had begun on her own head, the others created specifically for this project with the help of her hairdresser.

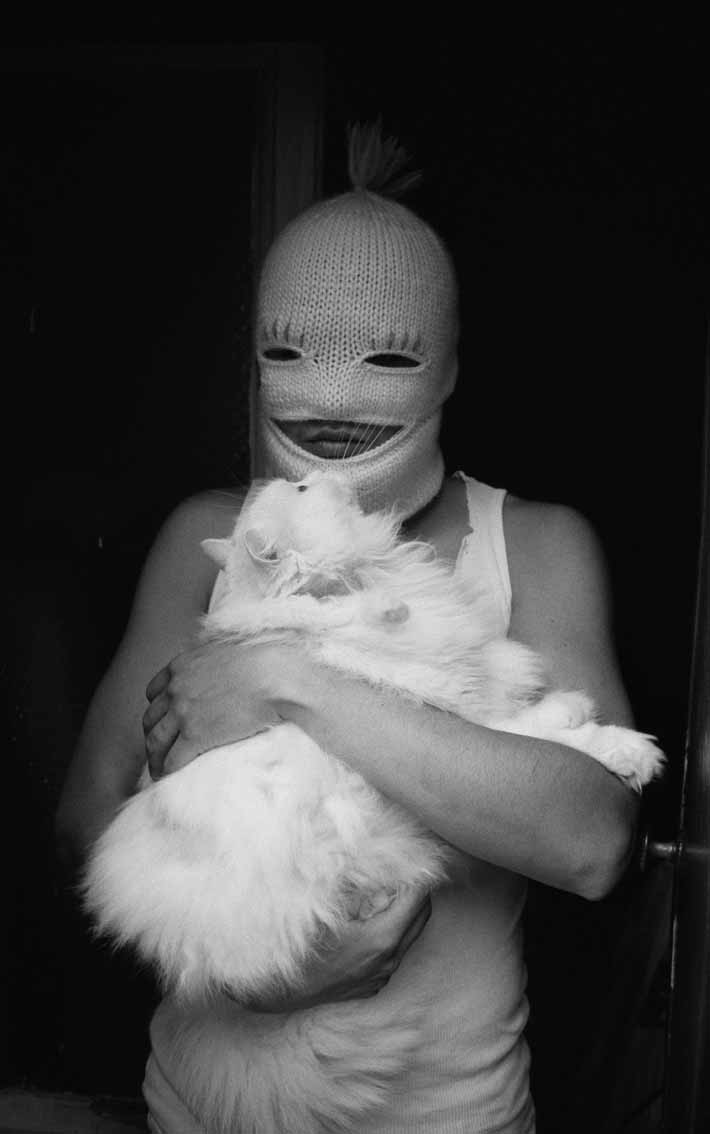

Above: 'Proud Lady'

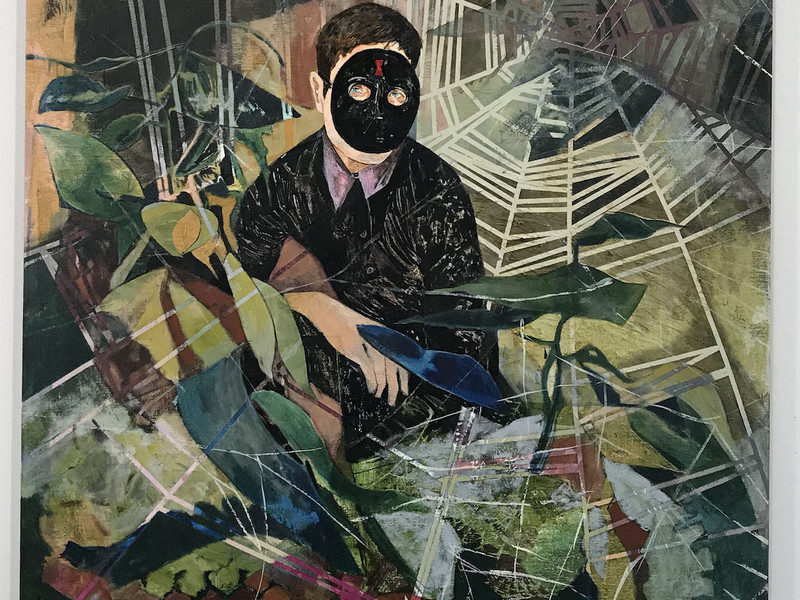

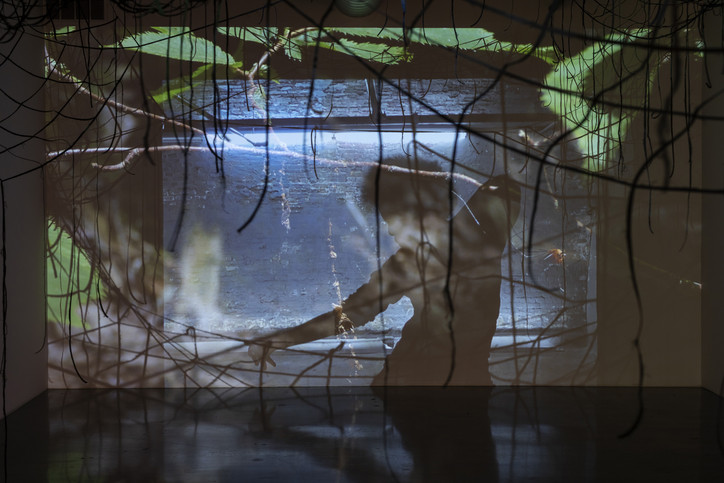

Miatta Kawinzi’s video work directly across from the hair wall makes a germane complement to it: an overhead web of elastic strips sewn together must be navigated through, whether visually or physically, in order to watch the video being projected on the wall, which is obscured slightly by the web, creating an intentional partial silhouette. The web, Miatta explained, is a wall that can be traversed, which relates to the content of the video, derived from the artist going on walks around Detroit and negotiating her way through crumbling walls of abandoned buildings, holes in fences, and other surmountable barriers. She was also thinking of string theory and the idea that you could exist both here and somewhere else simultaneously. Ambient singing plays overhead as well as snaps, a DIY soundtrack recorded in the shared studio provided by the residency. “I came across a text about spiders. I found out that spiders tune the strings of their web like a guitar, which is how they sense their prey. I became obsessed with this idea,” the artist explained. Understanding an environment through sound, as well as movement through space being simultaneously restricted and free, which is expressed through her physical presence on the screen, her slow, methodical movements set to her own music, became her central focus—especially in Detroit, where all these ideas actively coalesce (music defines the city, movement defines residents’ relationship to it). Poetry enters the work as well, letters dispersed across the screen must be pieced together, the words sometimes coming together, sometimes not. “English is a colonial language. I wanted to find my own relationship to it by breaking it up and specializing it, find a space of empowerment within.”

Above: Stills from 'Libration', by Miatta Kawinzi

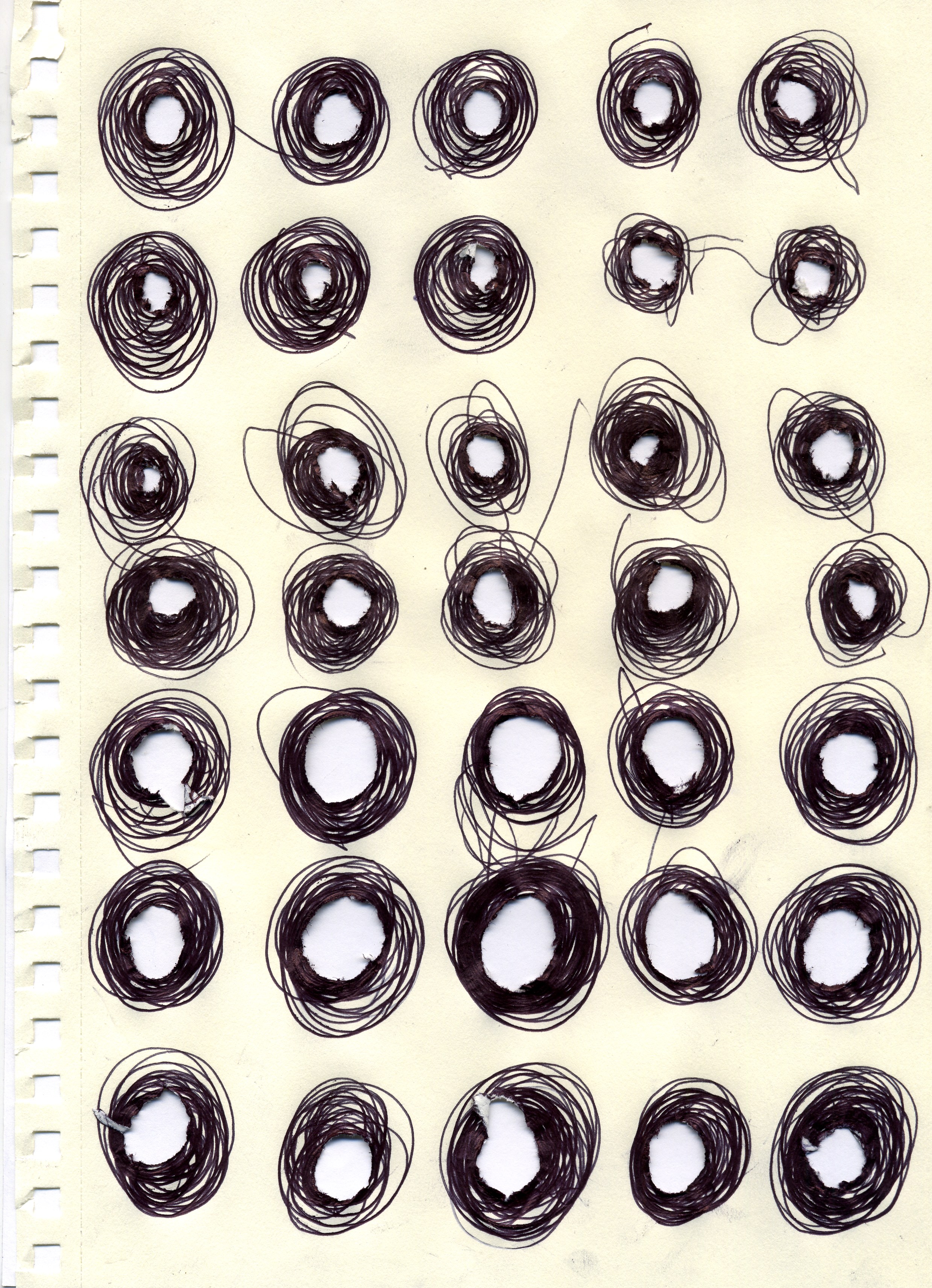

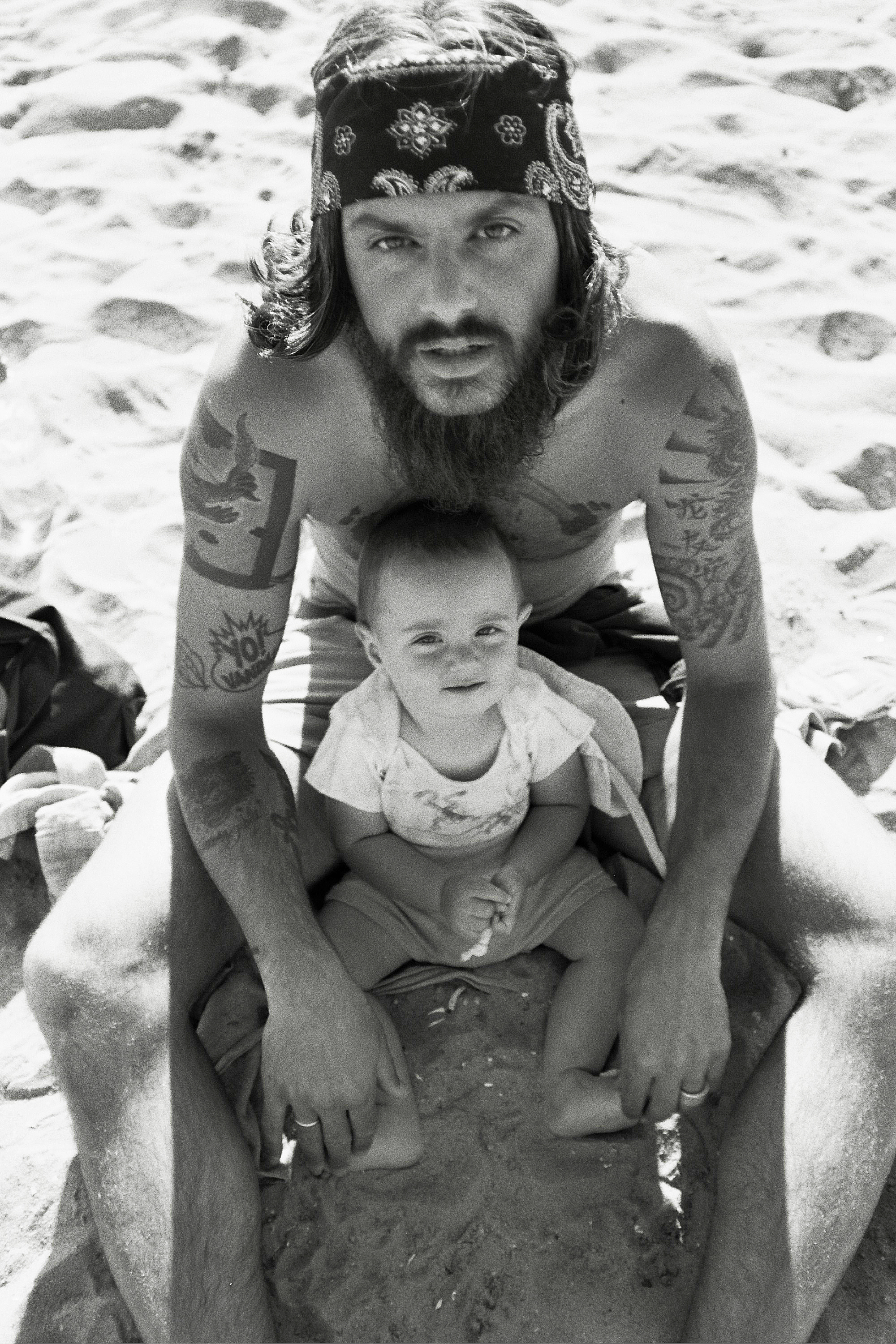

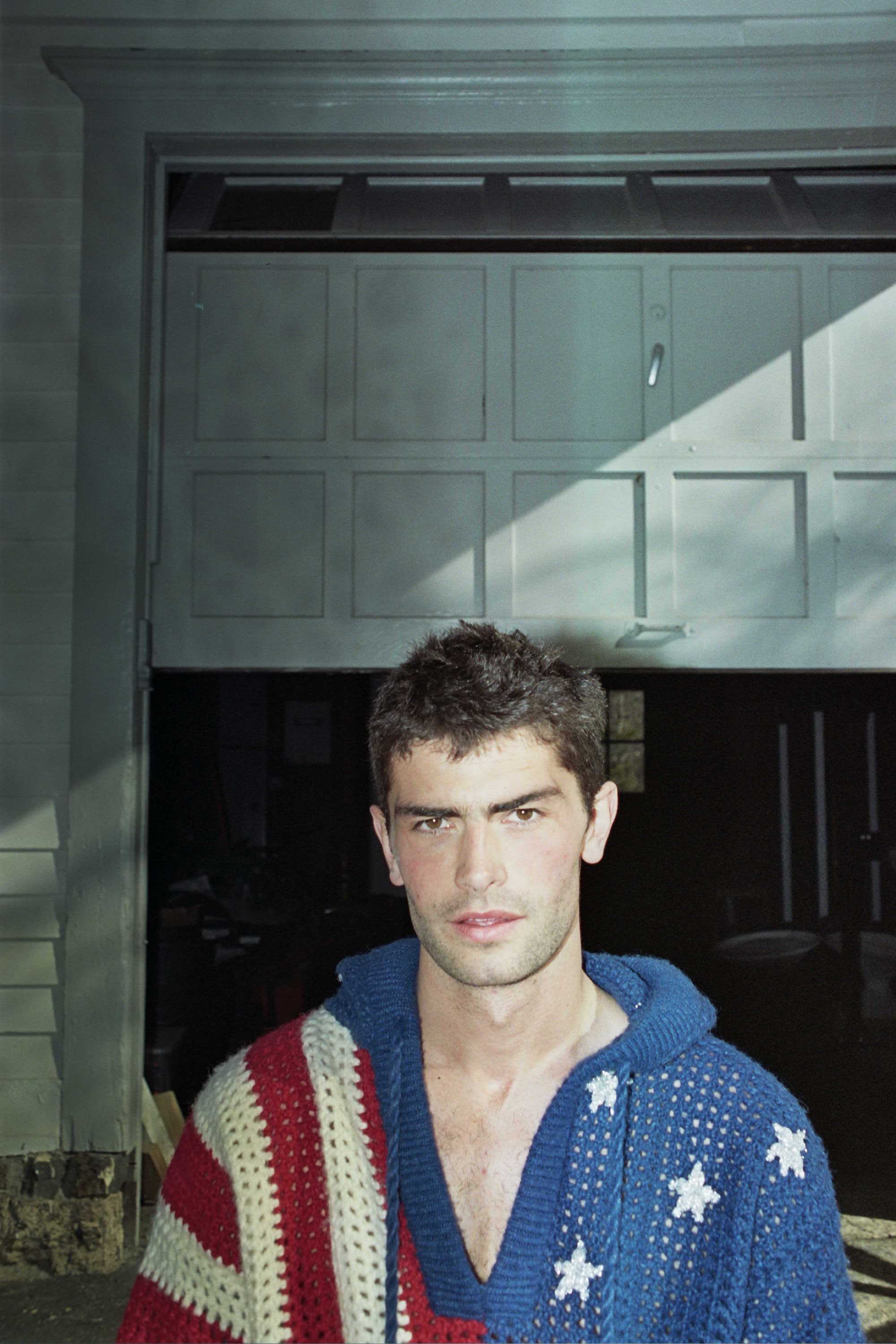

Patrick Quarm’s explorations through African fabrics ask pointed questions about movement as well, but this time across continents. His brother in Ghana, where the artist hails from, sends iPhone photos of fabrics for sale in Ghanaian markets, and Patrick chooses which he likes. The irony is that the fabrics are produced in Indonesia, so right away the artist is thinking about what can really be claimed as belonging to one’s culture, and if something can “belong” to a culture at all in a global climate of cultural hybridity. His paintings are crisp portraits that he produces at a rapid pace, consuming himself in the process. Many of the works take on a 3-dimensionality by hovering away from the wall and punched through with holes: “The holes are like reaching back into the memory, it’s in the past but we can still find it. I thought of it as a cultural archeology,” the artist explained. He’s thinking about his own past as well as that of Detroit’s, America’s, and Ghana’s—a clothes hanger from his father’s wardrobe is included in one piece, a suit the artist would wear to interviews hanging from it. It’s clothing as artifact, a totem to a character one is able to embody through costume. A young man in a pink hoodie looks apprehensively at the viewer, his eyes seeming to understand the loaded nature of the garment he has donned. Every garment has the potential to become as loaded, even just the fabric—beneath the holes the artist has pierced in his pieces, one almost expects to find the skin of a living breathing person, one caught between worlds like the artist himself.

'Resident Artist Exhibition: Miatta Kawinzi, Patrick Quarm, and Tiff Massey' is on view at Red Bull Arts Detroit through June 2nd. All images courtesy Red Bull Arts Detroit.