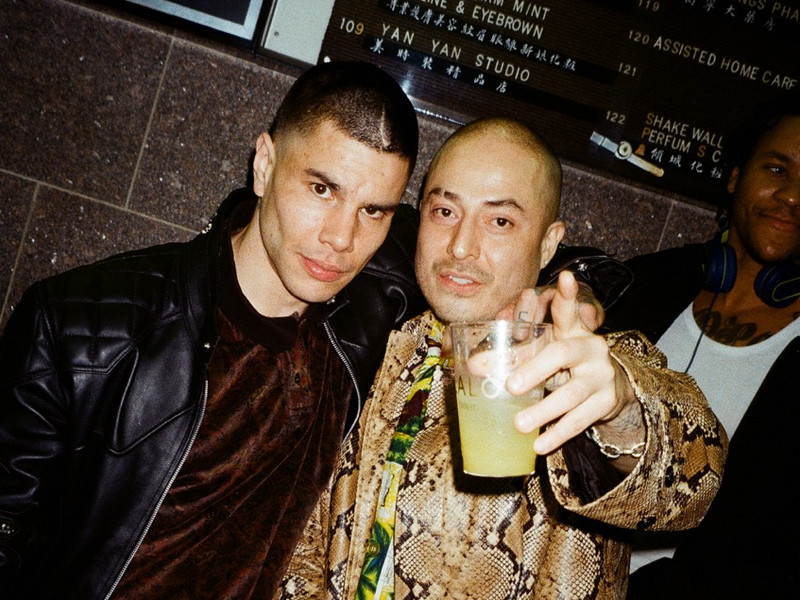

Where did you get your shirt from?

Wolfgang Tillmans: This is an artwork by Juan Pablo Echeverri, the Colombian artist with whom I became close friends and who passed away last year. It's the typeface of Metallica, which is this macho, masc band, and then the word Maricona, which is an exaggeration of gay: “hyper gay”.

I was reading in an interview that you did with [Slavoj] Zizek where he was talking about his resistance to the one-line autobiography, and he gave his parody of one. I was curious, over the years, has yours changed? And do you have one that you use when asked? Who is Wolfgang Tillmans?

I don't find I have to give a one-line narrative other than in a taxi or at a dinner where I end up randomly seated next to somebody who has no idea who I am.

In those cases, questions only arise once I have made it clear that I make art, because then, they want to size me up. Most of the time, they quickly tell me about an artist they know, often someone in their family. People are not as interested in artists as they are in telling you about an artist they know.

But my answer to your question hasn't really changed. I'm an artist primarily working with photography and installation––sound and video––based in Berlin and London. Since 2011, I have spent most of my time in Berlin, but maintain a connection to London, where I've been for 33 years now. I also lived in New York in the mid-90s, and after having taken some time away in the 2000s, I've been feeling really close and connected to New York again. I have spent summers on Fire Island for the past decade or so. The New York audience has been an incredible sparring partner for me and the museum show [his MoMA retrospective] last year was a years-long engagement with the MoMA team, the gallery [David Zwirner], and so many friends and amazing intellectuals.

Congratulations on the MoMA show. You have talked about this exhibition as a step in a different direction, or at least a fresh breath of air for your work. I'm curious to hear what that new direction is.

I haven't announced it like that. For me, it's more the obvious question of what to do after a retrospective of 35 years in one of the most prestigious museums, where I was given the most generous exhibition space. I was, and am, totally happy about everything that I experienced and that I was able to show. Now I am asking the predictable question, what do you do after it?

In December, I went into editing mode and looked through three years of photography and work, which took three or four months. I critically considered what photography meant to me and what I could do for it. Oftentimes, I work on photographs a year after I have taken them.

Nothing in “Fold Me” has been seen before, even though they sometimes date older. At the end of this excruciating period––looking at all the pictures, including the bad ones, is terrible and despairing at times––there was new work that is still fully engaged with the world. It is also in continuity with what I've done before. I like that idea. That the new is not a break from the past, but is somehow always an ongoing conversation.

You certainly have the status of someone who captured the 90's. What is the connective tissue between the work that people will see in “Fold me”?

The strength of the reception of the 1990s work at MoMA caught me by surprise. This was a rare example of an exhibition I strictly organized chronologically, so people were hit with an energy in the first three rooms.

It is good and all right that it made that connection with people. I made that work in my 20s, which is a unique time in life, a peak of firsts with constant experiences and reactions. As an artist, you are responding with an energy that is hard to maintain later. Fortunately, I still have that curiosity for people, places and objects. I have maintained an interest in seeing things and people with an open heart and curiosity, and still have a desire to represent them in a way that doesn't bend them into something they are not; this is the naturalism I have developed as my language.

I think it's a nice sentiment. I think remaining fresh to the world is a core tenet of a life well lived. It is a beautiful idea to be young forever in that way. Was it emotionally difficult, knowing you summited one of the greatest peaks of your career? I don't know if it's credibility, you said prestige...

Prestige is really not what I would like to say that I’m after. Prestige is an expensive watch or something [laughs]. No, no, a prestigious award is actually a good thing. It is hard for an artist to arrive because our general driving attitude is achievement oriented. You want to break down barriers. You want to open up doors and you want to get into a place or into a position.

23 years ago, in 2000, a close friend of mine said after I won the Turner Prize, “you've done it, you can stop. You've done it, and it's done." And I was like, "What are you talking about?" MoMA holds a certain uniqueness, but you cannot make an illusion for yourself that there is another climb from there."

Sorry, I just realized that I'm just getting a little lost in too much of this career introspection and self-assessment. But your question was much simpler, was it emotionally… what was it?

Difficult, but perhaps difficult is a bit course.

There are two things. One thing I still notice to this day. One could quite literally call it trauma, although a positive trauma. Trauma in medicine means a heavy impact. It was undeniably a heavy impact to my whole system that has had immense aftershocks. I feel very grateful that I came out of it in one piece and happy. I didn't fall out with anybody or anything, it was all good.

The other thing was a feeling I experienced on the third and fourth day of January this past year. The exhibition had ended on the second, and I woke up happy. I wasn't sad that it was over, but I was happy that I didn’t have to think about it anymore [laughs]. It had been hovering around me for years, and was finally just done. Then I got excited about the AGO in Toronto which turned out to be a really beautiful, completely different installation of the same material. And now I'm headed to San Francisco at the end of October to prepare for an opening of the exhibition on the tenth of November.

I was thinking about essay films while viewing “Fold Me”. There is something cinematic about your work. But instead of temporally, ideas are organized across space. Unlike in film, I have my own agency as a viewer to chart a course through your exhibition. How much ambiguity do you allow for in your galleries? How do you balance the tension between your aesthetic vision and a viewer’s interpretive agency?

That is a good question considering what I've been thinking about the past couple of weeks. There is so much interesting information I could give about each photograph, and on the other hand, it seems hard to give it in equal amounts about every work. How should I dose it, and how should I dispense it? You could make an audio gallery guide. And everybody would walk around with their headphones. And you could write three sentences or have a limit of 200 words…

[Wolfgang takes out his phone and moves to the window to snap a photo of the neighboring Frank Gehry designed building. Throughout our conversation, the light has changed dramatically, and the building’s windows are an incredibly dynamic surface]

Sorry I can't resist; I have just been noting the light this whole time…

And I can't resist photographing you photographing this.

No, please. One thing I don't like is being photographed photographing. They look the same. All photographers look the same taking pictures. It's like this bent over, hunter-ish, elongated pose. I find it strange and aggressive, and it doesn't tell you anything about the truth that the photograph might reveal.

It's deleted.

I mean, for your own memory, keep it, but please don't post it.

I guess that's quite indicative of how I am wired. I just couldn't resist my interest in what I saw just there. But, back to the topic at hand. Would it be interesting for me to tell you about this Frank Gehry building, and the architecture it is reflecting from across the street, and maybe a little bit about windows? Do you really need to read about windows?

For “Fold Me”, I decided that I couldn’t give an explanation for every picture. On the other hand, during my press walkthrough, I did provide some opening windows for people to make connections across the works. But in contemporary art, overt self-explanation is heavily frowned upon; it's considered “not cool”. And for a good reason. You are already in front of the art. You are “in” the art when visiting a gallery, concert, or cinema, and you have ideally made yourself 100% open to the artist's output. To then get an audio guide or a handout from the artist is perhaps excessive and would prevent you from feeling your own agency. I like to have the agency to discover myself in other people's work.

I have found that I haven't been overcome by a desire to explain too much. I trust that when the work is good, it will speak to 4 or 8 percent of the viewers. And then another piece hopefully speaks to 7% of another part of the audience. It's anathema to me to expect that everything has to communicate at the same level, intensity and intelligibility. From an early age, I liked when pop lyrics, New Order lyrics for example, didn't make much real, tangible sense.