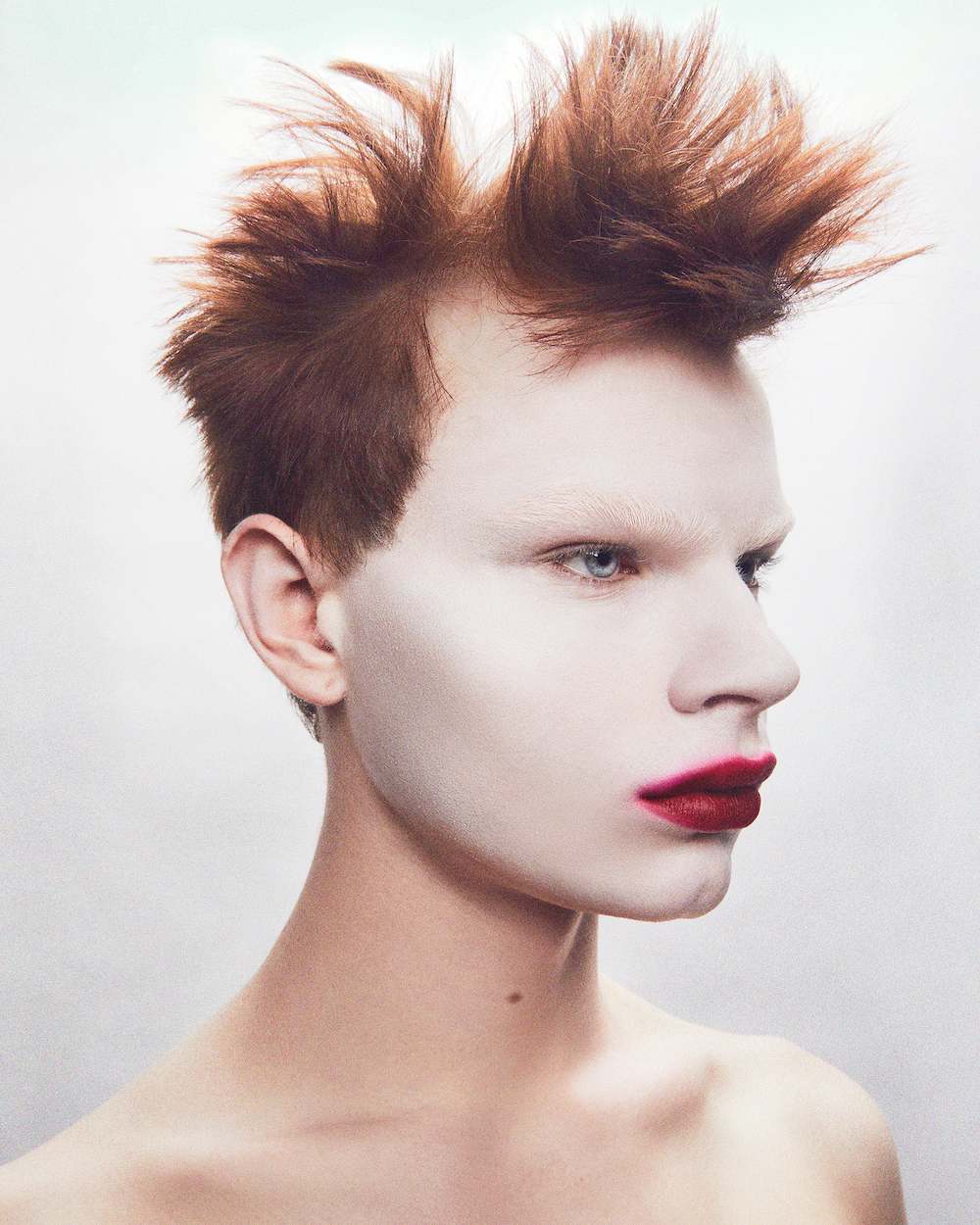

office — How would you describe your own haircut at the moment?

Holli Smith — I feel like I’ve kind of had such a boyish look for so long. I think short hair is ultimately always my thing, I think it’s the best thing. I decided to grow it out. I usually grow my hair out so that I can cut it all off again, and it feels brand new. Right now, I’m kind of just doing a top knot and painting my nails, still no makeup, no dresses, but touches of femininity to play with that don’t make me feel like I’m getting all girly. I feel like I’m doing a boy knot, but it’s definitely grown out. It’s all about being able to pull it back away. We’ll see what happens when it gets longer, how long this span of time will go before I shave it off again.

O — And what do you think is the worst haircut you ever had?

HS — I have really naturally curly hair. The worst haircut that I had was the haircut that made me decide I would take matters into my own hands and become a hair cutter. They basically bobbed my hair, which turned it into a huge mushroom, and then layered it really short on top. Even though it sounds like two different haircuts, it was very much that. It wasn’t a mullet, it was definitely a blunt bob. On top, it had sprigs. It was kind of like the girls in high school that have bangs that stand straight up, and then a few strands of bangs over their forehead, It was a short, bobbed version of that.

O — I have curly hair, I get it! Can see the horror. So–how did you get started in the industry?

HS — Well, I started from a cutting background. I started cutting in San Francisco. I went to beauty school out of high school, because it was kind of like the only thing I was interested in, and I could go to college for free. That just set up a little focus for me at such a young age, and I, luckily, got into learning to cut from a guy named Yosh Toya in the San Francisco area, which is where I’m from. It was such a great moment where people were really serious about their studies and hair, versus the beauty school I went to, which was just drop-outs and not an inspired environment. It was the first place I got really serious, and it was such a great place to learn, and to have structure, and to figure out what other possibilities there were. At that moment, I was really interested in music and visual style expression. And when you’re young, you don’t get to use the voice that you have when you’re older, so you want to dress up, and show people what you’re into by the way that you look. That became something I was completely fascinated with, and I got into fashion, or just the character behind the haircut. That got me into wanting more from just cutting. I always wanted to move to New York, and I finally did in 2000, and I just tried to figure out where I could learn to start styling, and learn about hair styling, and not cutting. They’re just such different worlds. You almost have to quit entirely one thing to get to be able to put yourself, energy-wise, into the other. Luckily, I got to get into work with Guido [Palau] as an assistant on a show, and then it just clicked. I was able to go on to the rest of the countries for the rest of the show month, and then he started working more in New York, and more full time, and I was able to be his assistant. I worked for two and a half years as an assistant full-time for him. Including shows, I worked for him for five years, and then I’ve been on my own for the last 13 years. I would say that during that time, I really learned about what I wanted to see out there, and what wasn’t being said, and started realizing that there was a mission to all of this, not just the commercialized reasons that people see fashion.

O — What is it that you think wasn’t being said? What was missing?

HS — Basically, I was just kind of sick of seeing men making women look sexy, and that that was what was cool.

O — My friend Laura calls it “Victoria’s Secret hair.”

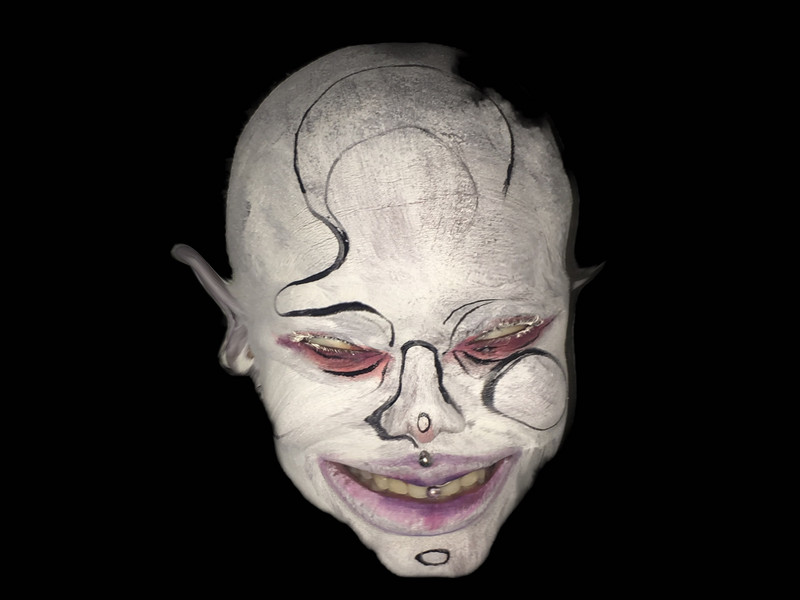

HS—Yeah. Wet, greasy skin, oily, blah, blah, blah. I know that that was just kind of a trend, and that’s how the business works. But I luckily have gotten to work with my girlfriend Collier Schorr, who’s a photographer. We really were lucky enough to get to make pictures that show cool people being a little more real. And I’m not crediting Collier or my work at all to being like, “We’re people who brought women into fashion,” at all. I just think what happened is that there came a time in the business when, after the economy crashed and budgets started changing, brands wanted to change their numbers and what they were putting into advertising, so it created an opportunity. The digital era created an opportunity for a lot of different people to create visual candy in a different way. Instagram and all of that is very influential in terms of not having things be so overly [manicured], not so squeezed of life. I just think that opportunities came where now we see a lot more women getting chances. There are a lot more artists, a lot more brands just willing to give a chance to a photographer who has never done fashion brand advertising ever, to just try and get their take on something. That’s what we do at Balenciaga. We have different artists that come from high skill to brand new, that have their own aesthetic and who have never done a fashion project before. Some brands want to do stuff that’s completely different than the script. Anyway, I feel really lucky that I have had the opportunity to create a voice and become an image maker with Collier. And on my own! We work on a lot together, but we work a lot separately. I’ve arrived at the right time. I feel proud to see that women are being looked at differently, not just as objects.

O — When did you and Collier start working together? And what is it like to work together? Is it easy? Do personal things get in the way?

HS—For sure, for sure they get in the way. [laughs] We met at a shoot. We knew the same friends, we live in New York. But she’s a little older than me, she’s been in New York full on since the ‘80s, being an artist. I came in 2000. We’ve been inspired by our little paths in our generations. They’d cross over in certain ways. I think we just had to figure out a way that we got to say what we wanted to say, but also figure out how to do that by letting each other do their own thing. I would just say that it’s really collaborative. I mean she’s definitely the person who has the ultimate say in things, but she’s really interested in what I have to say and my point of view. We’re having a really good time collaborating. But because you’re both doing things on a vulnerable level, it gets kind of sticky. We’ve definitely had a few years where it’s like “what you’re saying maybe hurt my feelings,” so then you have to talk about it more, and then you have to work through it, and then you learn, then the next time it’s really well worth it, because it’s beneficial to the next picture and the next shot. We really trust each other, and there’s no doubt that we’re on each other’s team. We’re also protective of each other. We just try and keep open and keep questioning, “Does this seem right? Does that seem right? Yeah that looks good.” But I don’t know. It’s fun. It’s really fun because otherwise I would just be someone who gets to do hair—which is fine, but if you don’t really know what the whole picture is going to be or what the idea is, it’s definitely not as joyous. You don’t get as much from the hairstylist as you can get without having this level of participation, and it’s the same with makeup and the same with clothing, I don’t know. It’s been a lot of work, but it’s been something on its own that’s really great.

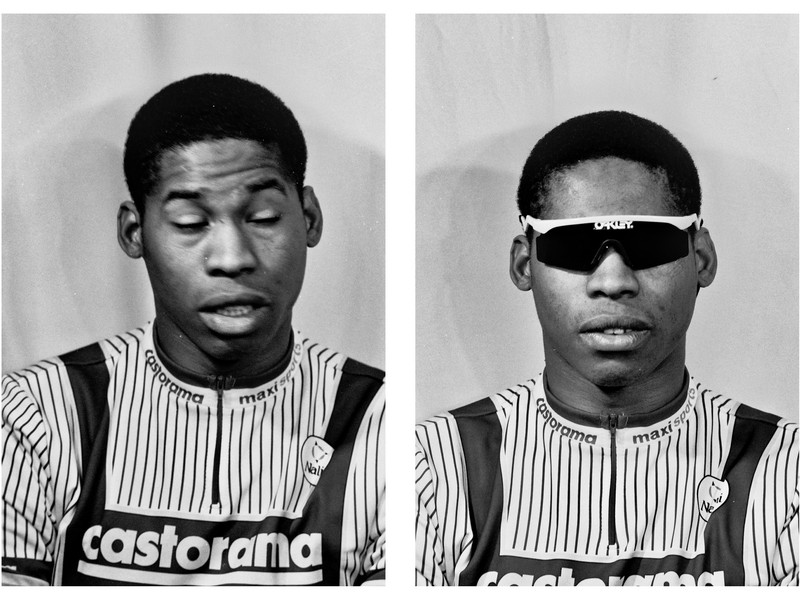

O—You’ve talked in previous interviews—and this certainly comes through in the work—about queer haircuts and the power of visibility. Is it important to you to represent queer aesthetics in your styling?

HS—I think that it’s almost already out of date to have it be explained that way, but that was my generation. Everyone’s fluid, if you will. I mean as overused as that word has become, when you look at children, all the boys have long hair, and all the girls have short hair nowadays, and that’s the thing that they grow up knowing. When kids come and see me and they’re like 16 or they’re 20, they don’t know that everything is flipped upside down [compared to previous norms] which I think is really good and important and kind of normalizes everything. Whatever your set gender preference is, for me, I’ve always wanted to be able to give people a [representation] of what is inside of the person that isn’t being said on the outside, to try and find what that is. That’s the thing that I feel about people who want to have visibility in queer culture. I think everybody has a puzzle, a little thing to figure out deep inside. When I used to cut hair full-time, it didn’t become full on psychological, but you do have to find out some historical information. The way to make something come alive is to figure out what a person has inside of them and bring it onto the outside with the haircut. That’s why I always think hair is such great material to play with.