Behind Gelatin Labs: Meet the Kruegers

Henry Whitford: Did both of you guys grow up in New Jersey?

Ben Krueger: We did. I grew up in South Orange.

Doug Krueger: I grew up in Union.

Doug, when did the photography thing begin for you? Was it something that started at the beginning of your life or did it come around later?

DK: My father would shoot while growing up, definitely more casually than anything else. The camera he would shoot on was a Canon A1 which would eventually end up in my hands at the age of 13 or 14 years old. My passion eventually started growing at the age of 21 when I picked up a Yashica T4 brand new from the store. I still have that camera. I still shoot that camera. Henry: Did you get this Camera in the city? Doug: Yeah I got that in New York City. I was working in New York City at the time and I dropped by at a local camera shop afterwork. Picked up the Yashica and the guy working behind the counter said to me, “Oh, you're going to love this camera”. From there, what really kicked me into high gear was when I took the camera on my honeymoon and I came back after going to Portugal and I was showing some of my photos to some family members, and they said, “Wow you really have something. You really have an eye.” From there, after getting some encouragement the photography took off, and then I was full force into it.

That's great. I'm always curious to hear about the story where someone's interest in photography begins. I have another question for Doug, when you were first shooting, were you doing the processing yourself?

DK: No, I was just going to the local labs at the time. For me, it was more about the shooting and that whole process of creativity on that side. Back at that point in my life I never had any interest in the processing side of photography. It was not until this journey of starting our own lab began when someone had moved us to go buy this machinery for processing did we start figuring this shit out.

And what was that learning curve like when you guys dove into the processing side of the film world?

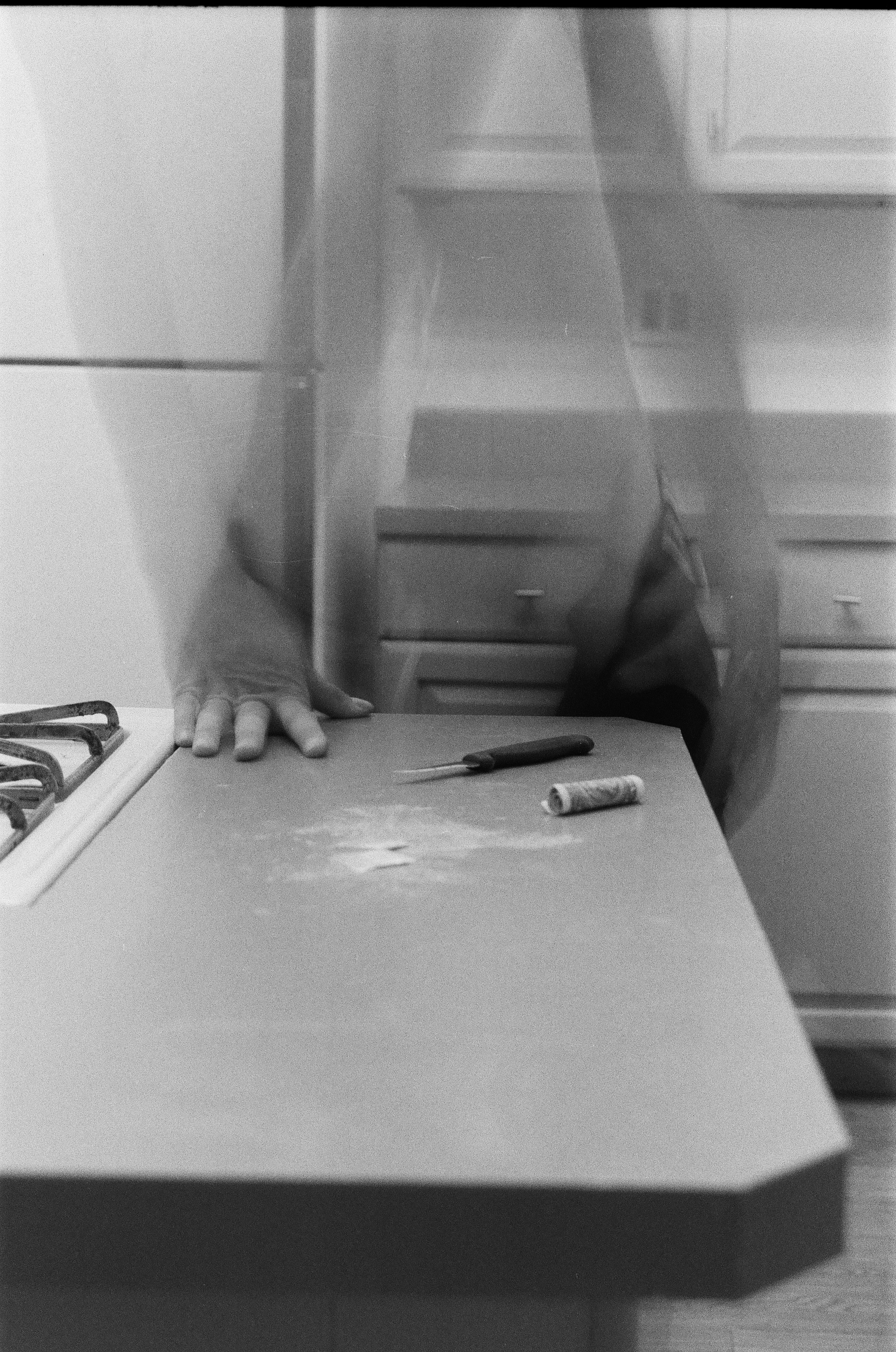

DK: So what happened was in our naivety, We found a place, I guess, online that was selling machinery. And then, Ben and I were like, Oh, it'd be cool if we could just come home and start scanning our own photos and do our own process.

BK: We also wanted to archive all the negatives that Doug had shot over his lifetime. But, also I was really getting into analog about nine years ago. Once I was on the analog train again, then Doug got back on the analog train after being on the digital train for so long. But with wanting to scan negatives of photos taken of our family we wanted to get the best possible scans possible. Which pushed us even more to take on this challenge of doing it ourselves because the majority consumer options were average. Which brought us down the rabbit hole of trying to find out what is available that is lab grade and can get the job done.

DK: The rabbit hole was that we found a wholesaler where we bought our first Noritsu scanner, the 600. While we were at the same place we went into the back and saw all these machines for developing film. The seller was trying to get us to buy one of the developing machines but we decided to hold out to see how the scanning would work out.

DK: Then a couple of months pass by and we think to ourselves that it would be kind of cool to own a developing machine. We're like, we could probably get it down to the basement. We go back, we pick up the machine. The guy brings it to us. Unfortunately, the machine had to get down these very steep basement stairs from the outside of the house. It's a 200-pound plus object. It's awkward. You don't want to break it. You don't want to drop it. Well, needless to say, we got it down there. But, man, let me tell you something. It was really like sweat and bullets getting this thing down.

BK: It took three months to get the machine running. Three whole months to get the machine running. I think that really, looking back on this, it's a testament to just how difficult it is still. There's no college degree in starting a photo lab. There's a lot of the legacy people that were involved in that industry that either want nothing to do with it anymore or have since passed because that was another era. There's a lot of figuring it out for yourself. But then there's the real issue because you have to constantly run the machine. Which we weren't really made aware until the thing was operational that you got to run the machine. At that time with that machine, it was at least 10 rolls a day, which we weren't shooting that much between the two of us.

BK: What we resorted to was reaching out to friends and asking them if they need any development done. And that's how the ball started rolling. During this time I was being trained to create what's called a flat scan and something that you can work from the negative that you can tailor and edit to your liking. I was doing that, and we were dialing in our machines that way, and people started to take note of that when we were sharing our work on Instagram and when we were talking to friends. It was this moment where people were recognizing that there was something different going on here and we began operating as a pop up.

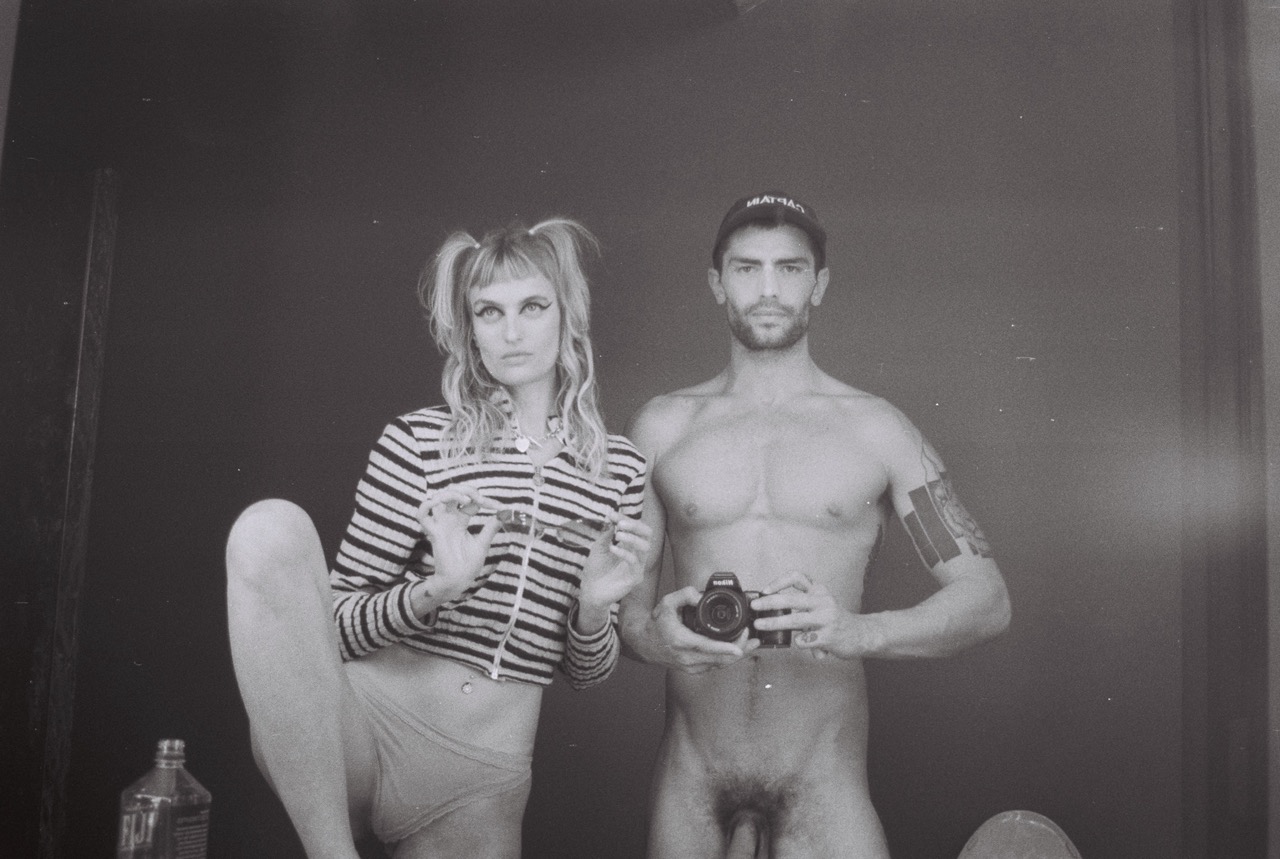

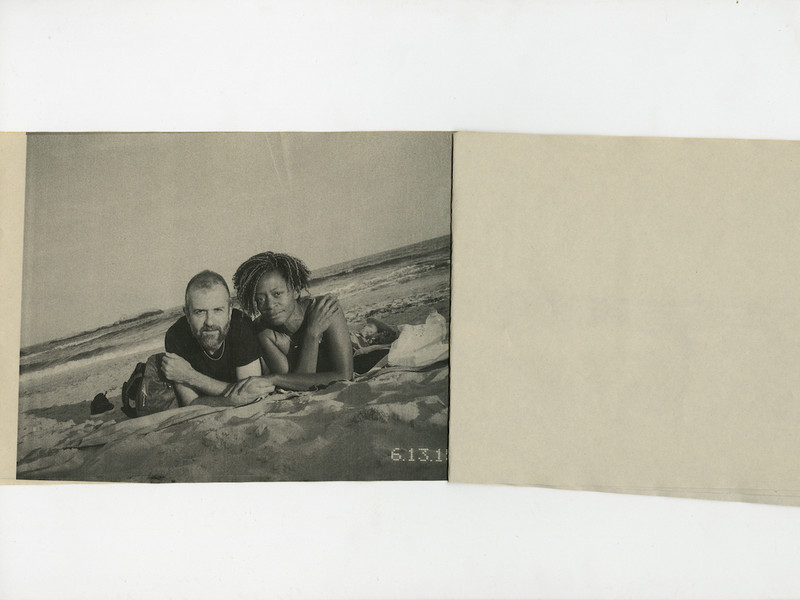

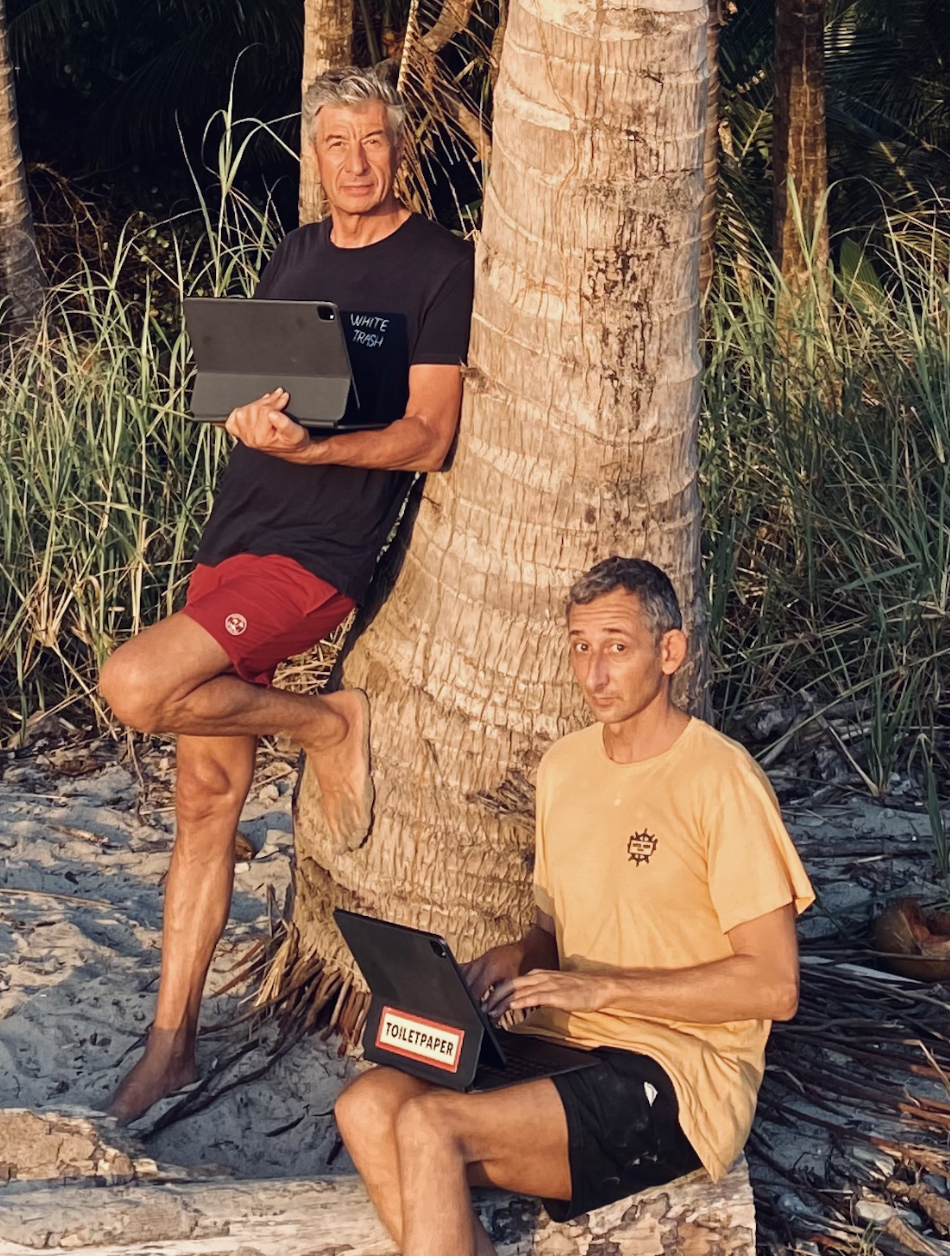

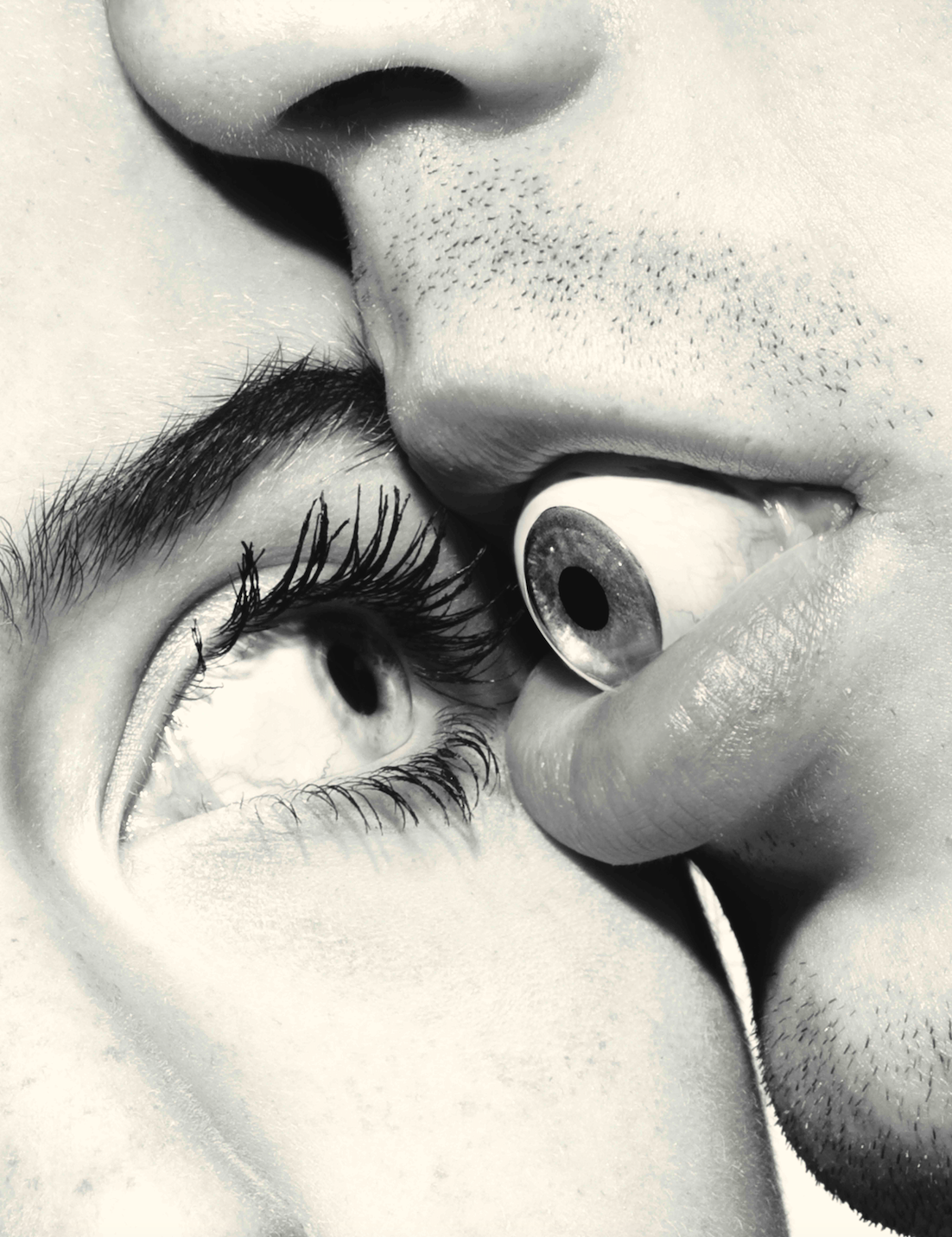

LEFT: Ben Krueger, RIGHT: Doug Krueger

How long were you guys operating from the basement?

BK: We started the summer of 2018 which is when we got the developing machine working. That's really where we consider the beginning of this because the scanner was the year before, but it wasn't really with any idea of creating a complete lab service. Then in December 2018 we started operating as a pop up. In short, we were in the basement from 2018 to February or January of 2020.

What was it like operating from the family’s basement?

BK: We had two machines at that point down there. We had probably about four or even five people working at a time on rotation besides us being managing the operation. The mail would come through the backyard, in these big bags and we would do this handoff in the backyard. Like a drug deal. It was a great place to kick things off. But once the fishbowl got bigger, so to speak, we really grew into that very quickly, and that's when we moved.

After you guys left the basement where did you move to?

BK: We moved just the town over to Maplewood. We moved into this really great commercial office building. Within a year of moving in I would say our team doubled. Then that's really when we could start growing things properly and taking it really seriously.

I saw on your website that you have dropboxes for film around NYC and even in Savannah, Georgia. I was wondering if you could elaborate on how these dropboxes function?

DK: The idea of the Dropbox is that we want to have a presence in neighborhoods. We want people to be able to feel like they don't have to ship their creative process. We want to simplify the process as much as possible. Also a part of our other ethos is collaborations. For example, in New York City, we have a drop box in a store called Knickerbocker.

BK: With Knickerbocker it's very cool because it is more of a human interaction that occurs because you go up to the counter and talk to one of their team members, and they then provide you with the envelope to put your film in. In a similar fashion to the way people mail into us, all they do is they just place their order on our website ahead of time, and then they just fill the envelope, write their name and order number, and they can be on their way.

Is there anything that you guys do to keep your prices affordable for your customers?

BK: I think we constantly are evaluating not only our process, but we're very much on the page of quality first. Then I think that the benefit of having our headquarters in New Jersey is that we can have more space and more equipment and at a fraction of the price that it would cost to be building in New York. That also is a key factor here that we are a New Jersey-based lab that can service the whole country, and that you can live anywhere, you can mail to us, you can drop off at a box. But our headquarters being in New Jersey, I think allows us to keep prices affordable, which is important in a world where film is not a necessarily affordable medium.

DK: By having New Jersey function as the main headquarters for the lab, we have been able to maintain competitive prices and keep a very high quality product. A product that is in our minds, but also in our customers' minds, one of the best.

What would you guys say is your favorite part of being in this business?

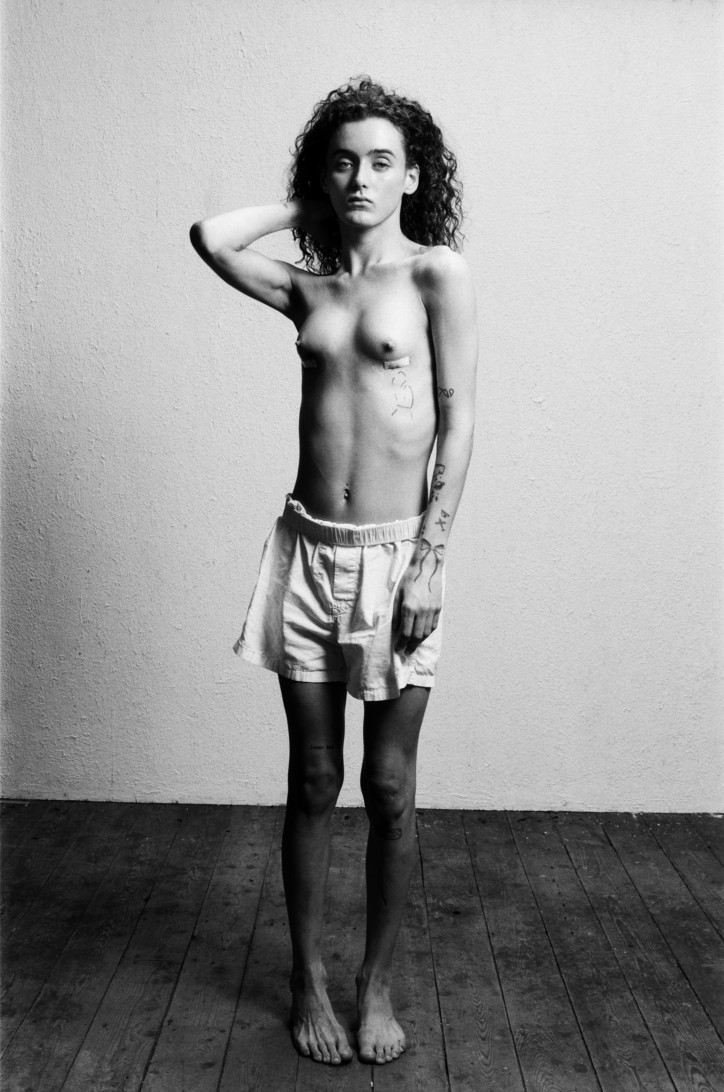

BK: For me there are a few things, one is I do enjoy working with our team. Our team is very passionate, and very committed to photography. Which is important to us because there is a connection that you can make to the quality of work someone will contribute to the team and the work that they're making themselves. We try to foster a creative environment for our time so that they improve their work and continue to work on personal projects. We conduct critiques where we talk about our work, and we always are interested in the latest developments in the community and in the industry.

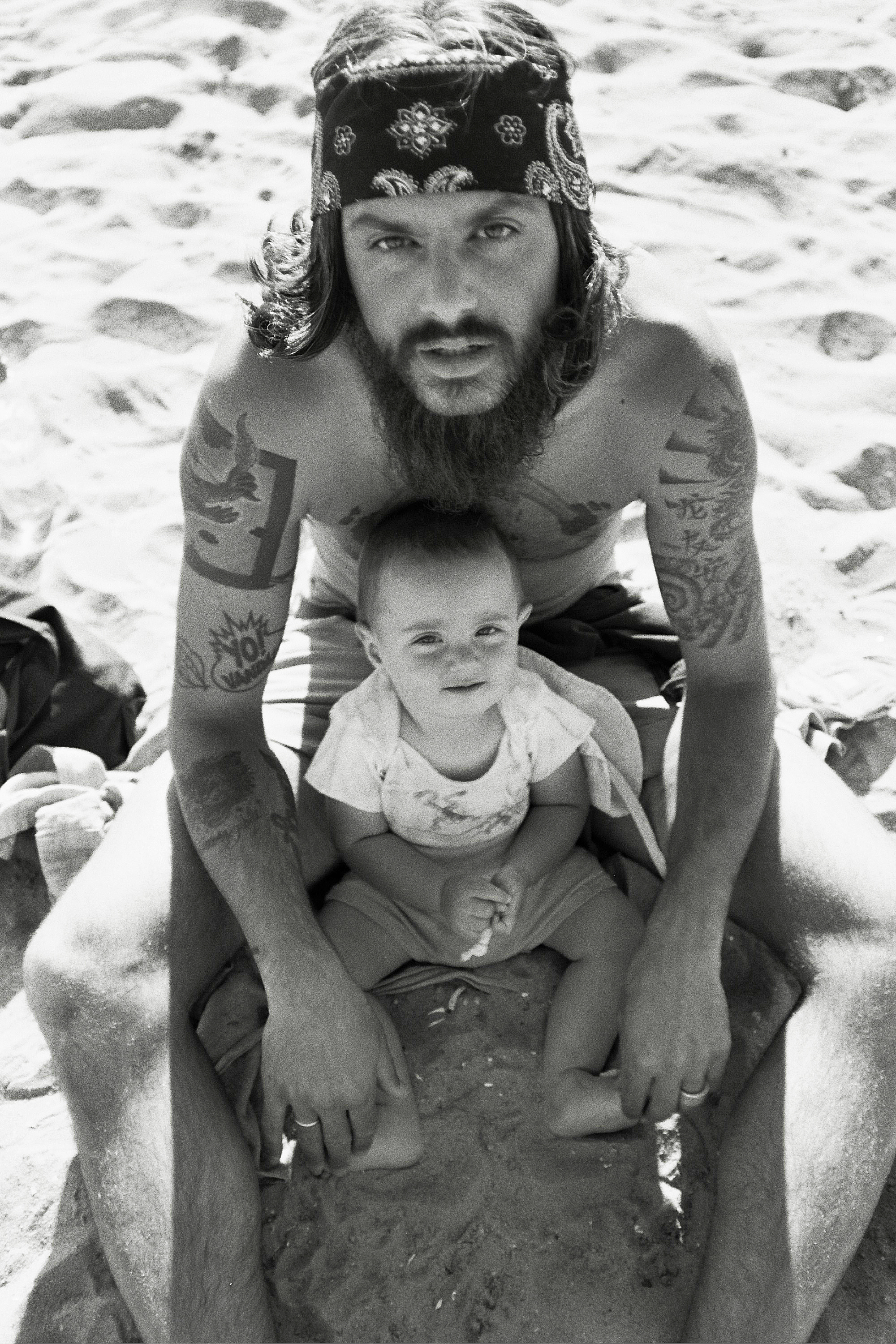

DK: I will add to that. I have just three points. One is being in business with my son, so that would be the first. Working together, going through the creative process together to work and to grow Gelatin. Two I would say is community involvement. What I really love is the whole community of photographers and the privilege it is to know a lot of these photographers, which to me is very wonderful and exciting. The third would just be, really, at the end of the day, building a business. That, by the way, is really the icing.

I also understand you take a lot of orders via the mail. What is that process like of shipping negatives to Gelatin?

BK: Yeah. I mean, 90 % of the orders that we fulfill are mailed to us. And we have customers in all 50 states. So that's been amazing. This business model really started during the pandemic where a lot of labs were closed, but we were operating out of our basement. A lot of the same clients that were using us then, still to this day, send us film. And we are continuously working on making that process as stress free as possible. We have even developed a serial number system that allows us to give our customer updates on every stage of the developing process.

With this business model of receiving film via the mail, do you ever find yourself excited about the fact that you have the privilege to see photos from all around the country?

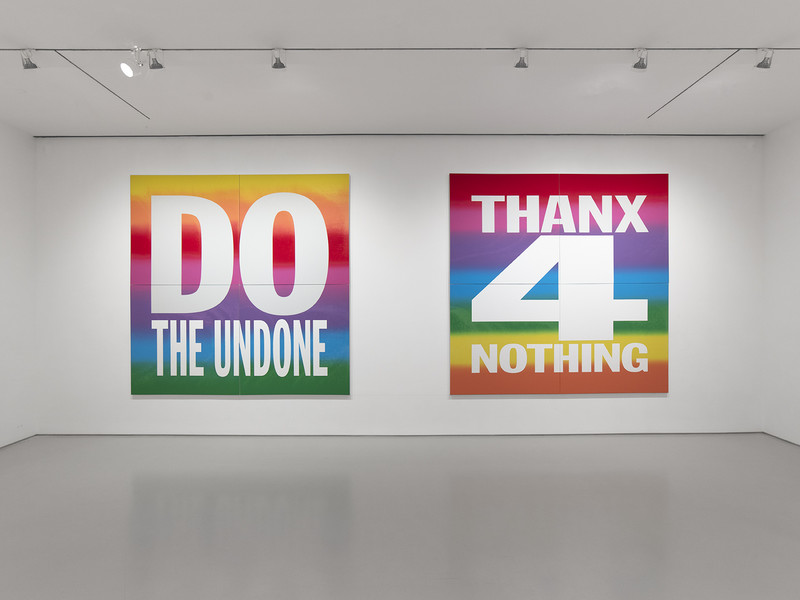

DK: I love it. I'm amazed by the passion and by the fact that people are still picking up a freaking analog device and choosing to spend more money. I'm touched by the fact that we are able to function as a central hub of where all this stuff is coming in and going out, and we're able to process all of this.

BK: I think that there's inspiration from getting work from customers and the community that's working with Gelatin. There's inspiration there for us to keep going and keep building. I hope that what we're doing is inspiring people to go out and shoot, and that by them shooting and sending their film to us, we then in turn are inspired to make that process better for them. I see people growing their communities, following their art, being a part of shows in the city. I think that that loops back to us and we say, wow!