Behind the Lens of A Political Cinematographer

Though politics has long since concerned itself with optics (and sometimes illusion), its rhetorical tradition lies in language. The political giants of the past are immortalized in fragments and phrases:

“The only thing we have to fear is fear itself…”

“Ask not what your country can do for you...”

“Speak softly and carry a big stick…”

These phrases convey policy and personality implicitly. Carefully crafted, and honestly orated politicians used language to create checkpoints of cultural recognition, and connection while their personal lives remained largely private. With increased media technology (first in radio, then TV, and, now, the all-encompassing internet), politics has become increasingly more personal, and its language less austere. Leaving us with a new kind of cultural checkpoint:

“I did not have sexual relations with that woman…”

“There's an old saying in Tennessee—I know it's in Texas, probably in Tennessee—that says, 'Fool me once, shame on... shame on you. Fool me—you can't get fooled again...”

“Do not come…”

In building public presences from our personal lives, our politicians have become more human, and more visibly flawed, making appeals to a public that has become less susceptible to the aggrandizement of others. Instead, we pursue authenticity, the crafting of which (however paradoxical) is central to any successful political campaign.

One of the main conveyors of authenticity is video. There is nothing more personal than seeing and hearing, the stories of individuals. While they may not have the repetitive power of a good slogan, or turn of phrase, video creates deeply personal worlds through which the public can understand policy.

Canada’s interest in politics was spurred, by force (or foresight) of his mother. In high school, Canada’s mom encouraged him to intern for Congressman Elijah Cummings in Baltimore. The experience “opened [his] eyes to how a politician like Elijah Cummings had to deliver for his district,” and, by way of answering all the calls that came through the Congressman's office, Canada “got to really understand the issues that were affecting people in the area.”

From there, Canada studied Visual and Media Arts in college, moving into commercial work post-grad. Living and working in New York, Canada became burnt out on commercial work, and, at the offer of a college friend, jumped at the opportunity to join Warren’s 2020 presidential campaign. Traveling the country across rural and urban communities to hear the stories of the people most impacted, and often least heard, in politics, Canada tapped into the creative reservoir which would inform his work going forward: people. “When you're talking to people, who are actually dealing with the problems, it humanizes the issue. It's not just a quote-unquote policy. No, because it's more than policy. It's about people.” Canada’s people-first approach centers individuals who have been historically marginalized. In doing so, Canada builds relationships with viewers, pushing some outside of their own experiences to remember they’re voting for more than themselves or the candidate, and finding ways for others to feel seen, heard and reflected in a previously exclusionary discourse.

Canada’s intent both works within and subverts the rhetorical context of social media, where most (but not all) his videos are shared. Knowing how algorithms prioritize pictures of certain people, and censor posts with certain phrases, Canada has learned to work within and around the limitations of these primary platforms for political discourse. “When crafting or telling stories we have to be very aware of this and convey them in a way that doesn’t allow for algorithms to hide these stories, especially if it’s about the people most affected by the issues, the algorithm will hide it from them.” Social media has undeniably reshaped the way rhetoric is processed and proliferated, creating polarization across political spheres. “On the other side, the algorithm will choose to put other kinds of media or visuals on someone’s timeline, because it knows that it will enrage them, so they’ll end up spending more time on the platform, and the platform will sell more advertisements.”

That’s why sharing physical space with people is intrinsic to Canada’s work. On “social media, everything's highly polarizing and politicized. But then when you actually go into other people's communities and talk to them, and break bread, you realize that we have a lot more that brings us together, then tears us apart.” Giving root to otherwise intangible ideals, the landscape of a video can communicate the physicality of political divisions.

Canada found a stark example of this in his visit to 48217, the most polluted Zip Code in Michigan, for Warren’s presidential campaign. Canada recounts seeing an oil refinery and steel plant right next to a recreation center, church and kindergarten, and realizing the physical toll of a life lived within this scene. “I remember seeing all of these elements together and hearing about the rising asthma rates of kids and cases of cancer in the neighborhood, but somehow, somewhere, someone in power was just okay with this.”

Canada’s approach pulled from this storied space to flesh out the narrative shared by Senator Warren and Congresswoman Rasheeda. Pulling wide shots to highlight the looming presence of the refinery. “One of the activists told us that when they brought up these issues to their local politicians, their response was to plant a few trees between the toxic oil refinery and recreation center. Visually, the giant plant was towering over these little trees that were meant to be the solution.”

To illustrate Canada’s approach, we asked him to walk through a few stills from Mayor Wu’s launch video, in light of her recent win.

“In the first image is mayor-elect Michelle Wu, in front of Boston City Hall. When this video came out, it was a really challenging time during COVID. I feel like the video offered a slice of hope during a pretty dark time. And this photo right here, it just, it feels really positive. It feels hopeful. You know, she's looking off-camera, it looks like there's something around the corner that we're waiting for. And thinking about City Hall.. everyone in the city has a different relationship with the space. Some might see it as a large, unwelcoming brutalist building. But I think with the mayor proudly standing in front of it. She's looking to make this space accessible, and also to build a Boston for everyone—to build a city for everyone.

The second image, this one is one of my favorites, just because she does take the orange line. And getting the shot with the motion blur in the background, I guess the movement signifies some of the changes that people have been waiting on.

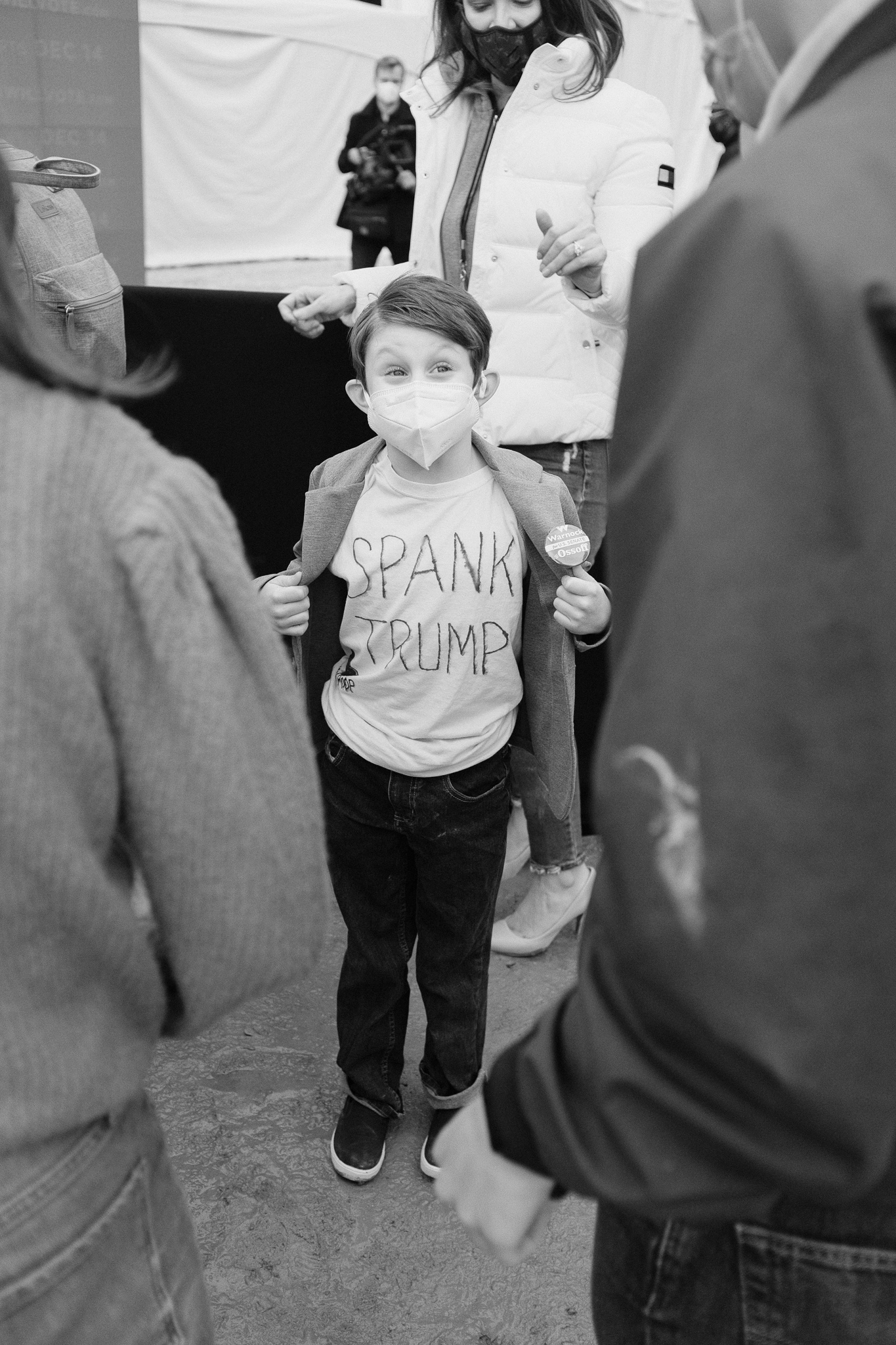

In the last image In this image, she’s helping a mother by adjusting the mask on her son. At the time, we were only a few months into COVID, still figuring things out, but Wu and the mother were working together so the child would be safe and comfortable while playing in the park. It highlights the care and attention to detail that mayor-elect Wu would incorporate into her COVID response. And seeing everyone masked in this image, and throughout the video, different generations - it communicates that this is a problem that affects us all.

In the video, I was happy to incorporate some 16-millimeter footage. Some people find that nostalgic or more personal because of connections that they might have to video, their family, and archival footage. So I always enjoy just shooting some portraits on 16mm."

Canada’s cinematography does feel deeply personal, conveying a comfort and rawness that often feels absent, or forced in campaign imagery. “I think with cinematography, the camera just lets you get closer to people, and the camera takes you different places.” To Canada, documenting a campaign is not about its eventual success necessarily, so much as paying respects to the stories wrapped up in each election. His goal for each project: to respect, reflect, and uplift. “I want to respect whoever I’m working with. I want them to feel comfortable. I think that’s really important.”