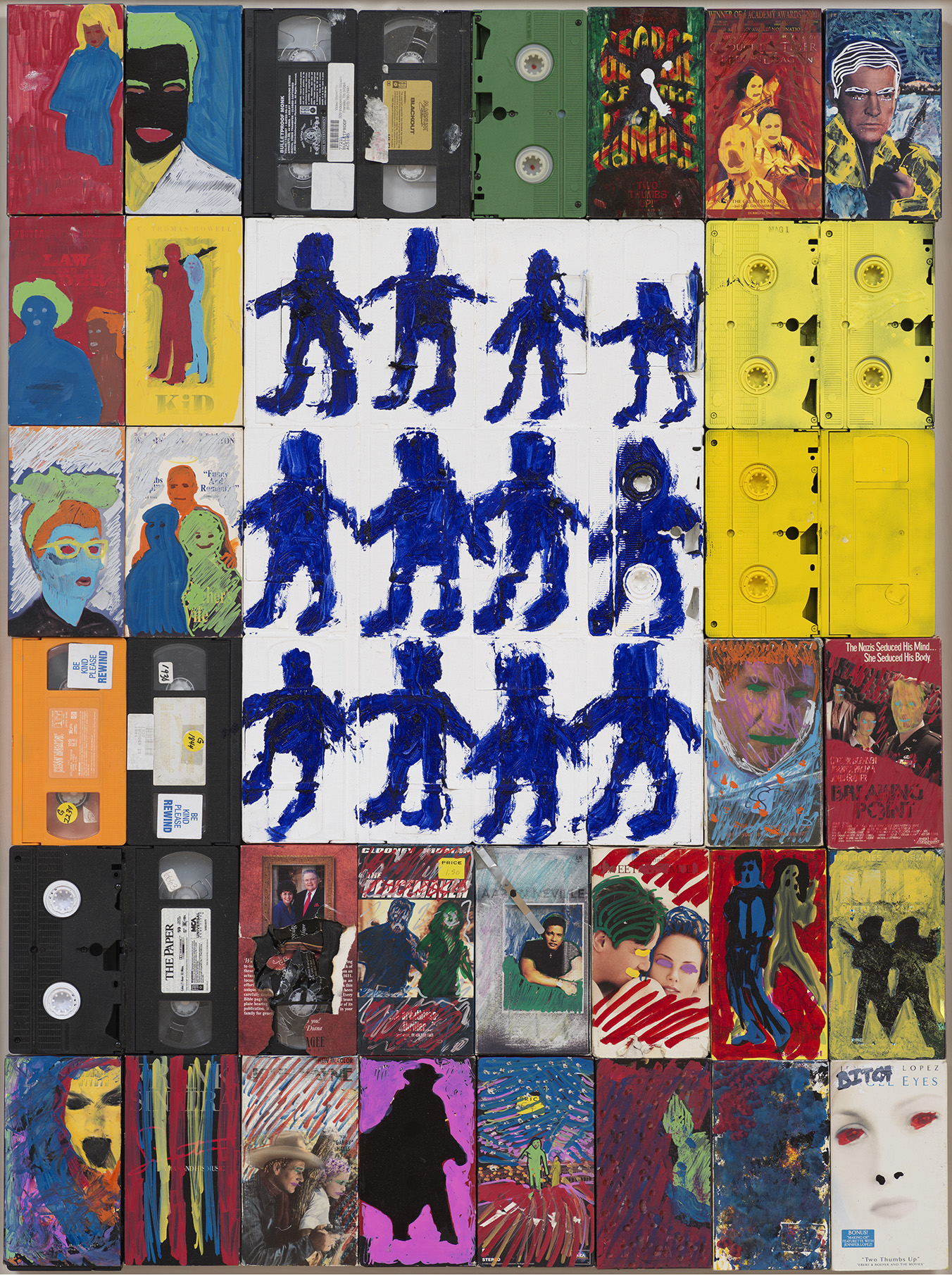

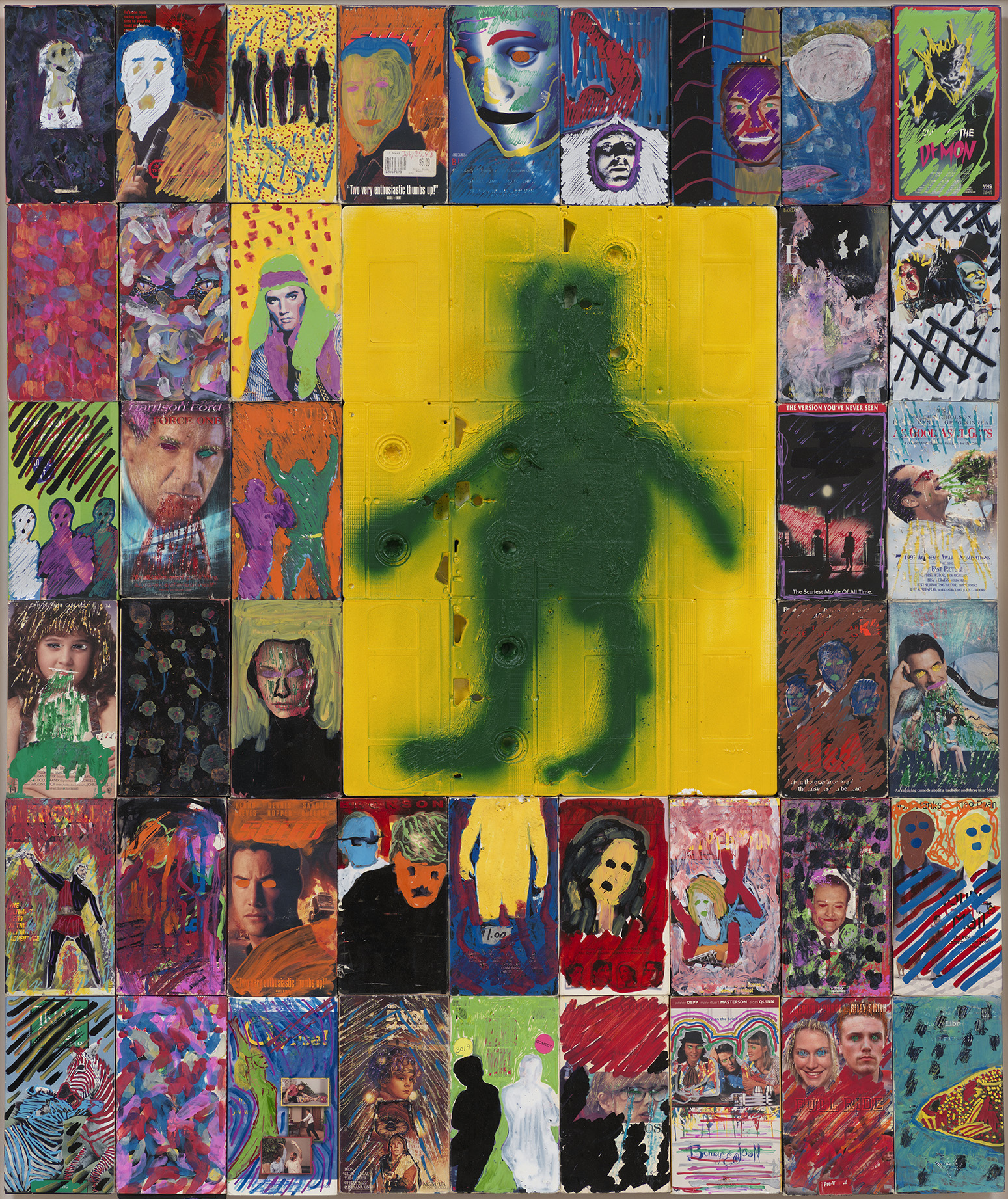

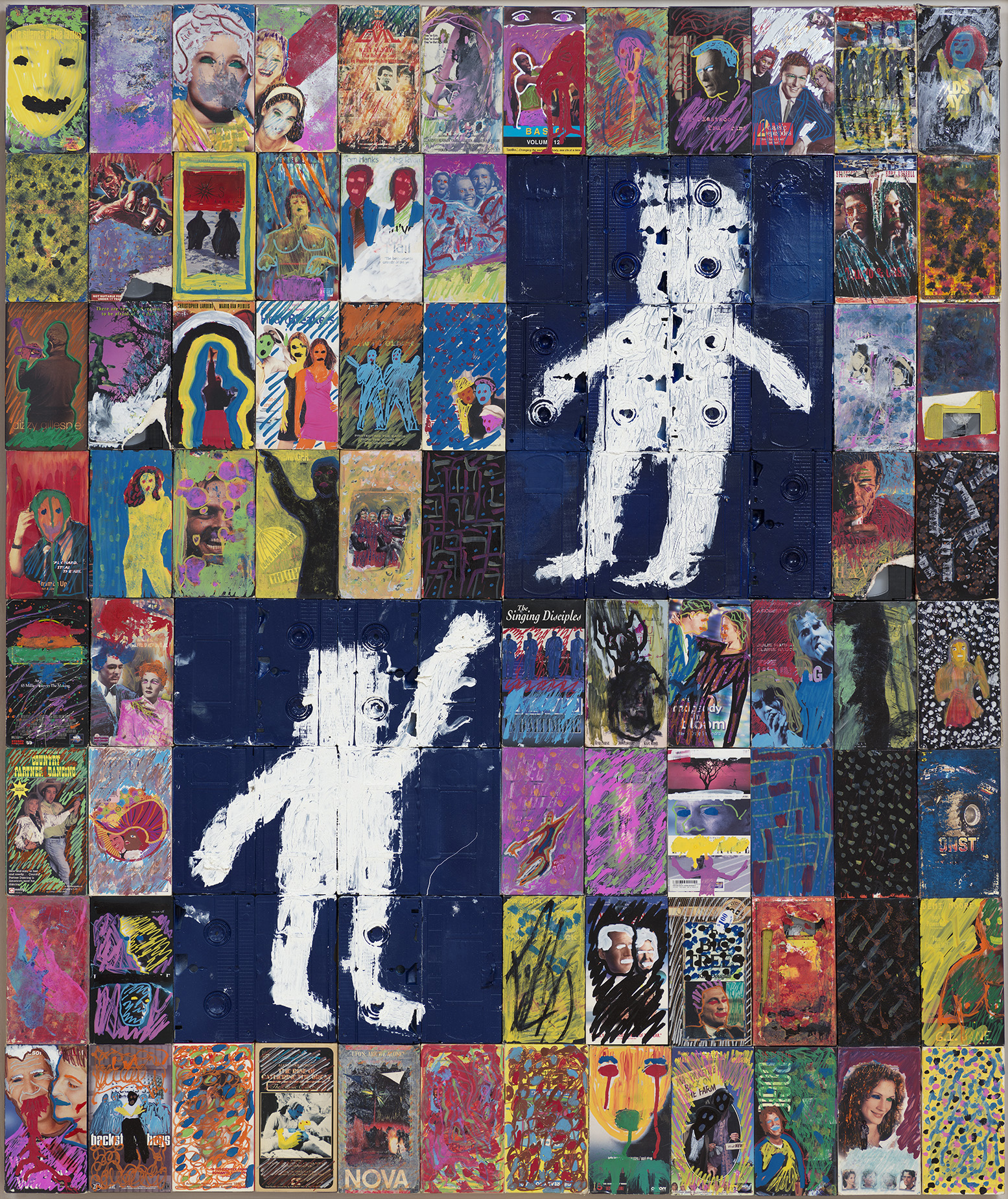

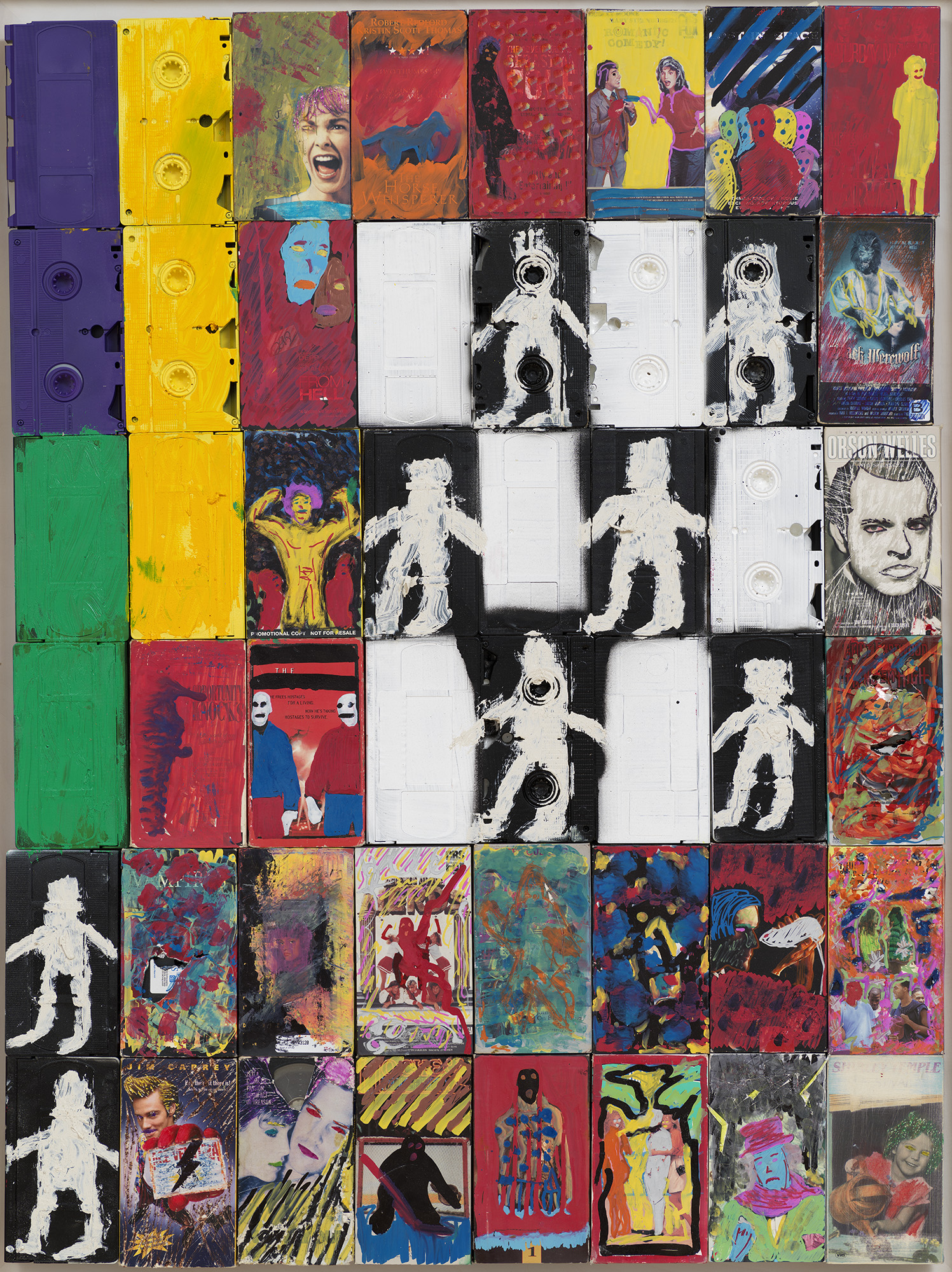

BLOCKBUSTER

Be kind, rewind—and peep some of Korine’s pieces, below.

'BLOCKBUSTER' is open now until October 20, at Gagosian in NYC.

Lead photo by Sam Hayes; art photos by Rob McKeever; all courtesy of Gagosian.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Be kind, rewind—and peep some of Korine’s pieces, below.

'BLOCKBUSTER' is open now until October 20, at Gagosian in NYC.

Lead photo by Sam Hayes; art photos by Rob McKeever; all courtesy of Gagosian.

Chiara — You have been living and working in New York City for the past 20 years but tell me about your first impressions of the city and what has kept you here?

Curtis — When I first visited New York City I remember being in the back seat of a yellow cab driving through Chinatown, I remember the energy of the people and bright signage; almost cinematic. It reminded me of of a scene from Michael Cimino’s 'Year of the Dragon'. It felt similar to an organized madness. I was both in awe and intimidation. It was thrilling and also disorienting. I think I was 20 years old. I had officially moved to NYC in 2005. Still today I find it to be a circus, it has no rules. Everyone intensifies what life does not need to be. However, in New York in order to survive, life must intensify. The city doesn’t just tolerate chaos - it thrives on it. The unpredictability of New York feeds creativity, pushes boundaries, and forces you to constantly reevaluate your place in the world. It’s this continuous engagement with uncertainty and possibility that keeps me established here.

What year did you start filming the construction sites and what attracted you to them?

I started filming on my daily walks around the neighborhood in 2010 or 2011. I had noticed that there was much more construction than in the previous years with the continuation of gentrification. The bigger construction sites that I was passing and paying attention to led me to thinking that there were really beautiful aspects to these environments. I chose to film it in a reckless aesthetic, and cropped them to highlight the details of this process. But innately I was composing things almost as still images, exactly how I wanted it to be. There were these really masculine construction workers, but at the same time a lot of feminine movements and hand gestures. I also filmed typical street work and maintenance, which are revealed throughout the film.

I think of your work as having a lot of movement; with your writing or even some of the other works I’ve seen, there's the gesture of the paint. Is there something to the movement of the construction, the machines and the hands that attracted you?

There is a connection, as an artist that is almost unconsciously doing. It was much more based on hands and these contrast features in comparison to what the idea of construction and demolition are in the first place. I think of swinging cranes and the machinery that's moving in a gestural way which has familiarity throughout my paintings. Every brush stroke strips the joy out of painting and at the same time adds to the general spirit of the work. The machines building, destroying, and rebuilding represent the continuous cycle of creation and reinvention that defines much of our human experience.

And then you removed the sounds of the construction and added in the music so it feels like I’m watching a dance.

Yes, it's a dance, like Bolero.

What do the machines building and destroying and building again represent for you?

They are reflective of my personal emotions, in terms of the idea of life and birth and destruction. Things going up and things coming down and thoughts going up and thoughts going down and all the feelings that go with that. But with these constant changes it’s still a reminder that we're all in it together to a certain capacity. It really just comes down to your state of mind.

Being a filmmaker myself I always love to know about the technical aspects. What did you shoot the construction footage with and how much footage did you end up having to work with in the edit?

Originally I was shooting on a mini DV camera but in too many instances I started to encounter without the camera on me so filming with iPhone was part of the process as well. I shot over 25 hours of footage over a three year period and the majority of it in the end was iPhone, shot in landscape format.

I’m so grateful you did that, I can’t stand this new-ish format for video on social media that has to be 9:16, literally the opposite aspect ratio of cinema. It drives me crazy. But I won't start on that tangent…Tell me about the clowns that have appeared in your work before. What do they signify for you?

Clowns have been a recurring motif in my work for a very personal reason. My uncle, who was a major influence on my life, had an obsession with clowns—figurines, clocks, calendars. He was a generous spirit, a mentor who introduced me to music, visual art, and film. But despite his affection for clowns, I always found them disconcerting. There’s something unsettling about the clown figure—it’s a mask for something darker, an attempt to cover up personal struggles with exaggerated performance. They symbolize a form of emotional repression to a degree. The act of hiding inner turmoil behind a forced smile. In my work, clowns represent the tension between the exterior persona and the internal reality, the mask we put on to perform for the world, while hiding our vulnerabilities.

I am not a big fan of clowns myself, they can be so unsettling. In this film you play a clown that feels completely hopeless and defeated and alone, with the weight of the world on his shoulders. I also found the contrast of that perfect blue New York sky, reminiscent of 9/11, which makes it even more unsettling. Tell me about this clown that you are playing?

The clown I play in this film is a reflection of personal struggle. He’s trying to maintain composure in the face of chaos, constantly caught in his own internal conflict. The perfect blue sky above him is in stark contrast to the feeling of hopelessness and exhaustion that he embodies. It’s as if the world is beautiful and calm on the outside, but internally, everything is spinning out of control. It’s about reaching the point where you realize you don’t have to carry everything alone, and sometimes stepping back and letting things unfold is the only way forward.

In what ways has the world gone insane for you?

There’s so much happening right now; the upcoming election, the climate crisis, the political turmoil. It feels like there’s this high vibration in the air and it’s hard to ignore - nor should we ignore this. I try not to let these things overly influence my studio practice. It’s hard not to feel overwhelmed by everything, but I also think there’s something to be said for finding peace within that chaos. I was trying to understand that character and prepare for the single shot at the end. At one point during the shoot I was naturally spinning out on current events and the state of the world.

Lastly, tell me about the score with the sounds layered in and the voices we hear?

I worked with Isaiah Barr, from Onyx Collective. We’ve collaborated on projects before. We generally sit with each other and the visuals and we piece together what makes sense in that moment. I have a soundbite from the Buddhist temple on Center Street and one of a younger British kid talking about money. I also added a soundbite of Stephen King speaking on the idea of "scary". Natasha Lyonne has this strong female NYC voice that can permeate, and Lennon Sorrenti who I’ve known since she was a child has this voice that just feels safe. I've used her voice for past pieces as well. It's a sound I will continue to make works with.

Your work often explores intimacy and vulnerability. How do you create a safe and authentic environment for your subjects during a shoot?

The past few months, I’ve been working on two series of photographs: nudes of women in their own apartments and portraits of women before and after giving birth. Both series involve capturing them in deeply personal spaces—bedrooms or nurseries—where they feel at ease.

Shooting in their spaces, in their own beds, plays a crucial role in creating comfort. I choose film and cameras that show them in a way they find beautiful and empowering, emphasizing softness and warmth. It's a stark contrast to modern, hyper-detailed phone cameras that sometimes reveal more than one wants to see.

Your photography has a distinct emotional depth and texture. How do you approach the interplay of light, color, and composition to achieve this?

My process is highly intuitive. I’ve never formally studied photography or apprenticed under anyone—I learned by experimenting and seeing what felt right. It’s about trusting my instincts rather than adhering to rigid rules.

What role do personal experiences or cultural influences play in shaping the stories you tell through your images? Many of your photographs feel deeply narrative.

Growing up, I was surrounded by great cinematography. My grandmother had a TV, but my mom only brought home VHS tapes—films with substance. I think that exposure shaped how I see the world, how I approach subjects, and the narrative depth in my work.

What role does spontaneity play in your shoots? Do you leave room for improvisation, or is everything carefully planned?

To balance spontaneity and structure, I go in with a clear plan and strong direction, but I remain open to surprises. It’s about letting the subject feel like the shoot is about them, not me. That openness often leads to the most unexpected, meaningful moments.

What inspired the shoot with singer LIA LIA? How did it come together?

Collaborating with Ruby and Naomi always takes me out of my comfort zone in the best way. For this shoot, we wanted to transform someone with an iconic face but also someone like Lia—someone with a clear sense of self.

Giving her a completely new look was exciting; it brought an unexpected energy to the set. The approach was playful and experimental. The night before, I had no idea what wigs Ruby would bring or what colors Naomi might choose. It was a beautiful mix of spontaneity and collaboration.

What inspires you the most?

Movies and music are big inspirations for me, as well as the work of other photographers like Carlijn Jacobs, Harley Weir, Rineke Dijkstra, Charlotte Wales, and Nan Goldin.

What emotions or truths are the hardest for you to express through your art, and why?

I don’t think I consciously try to express specific emotions when I work. Instead, I follow what feels right in the moment—what draws me in or excites me that day. It’s less about a deliberate expression and more about letting intuition guide the way.

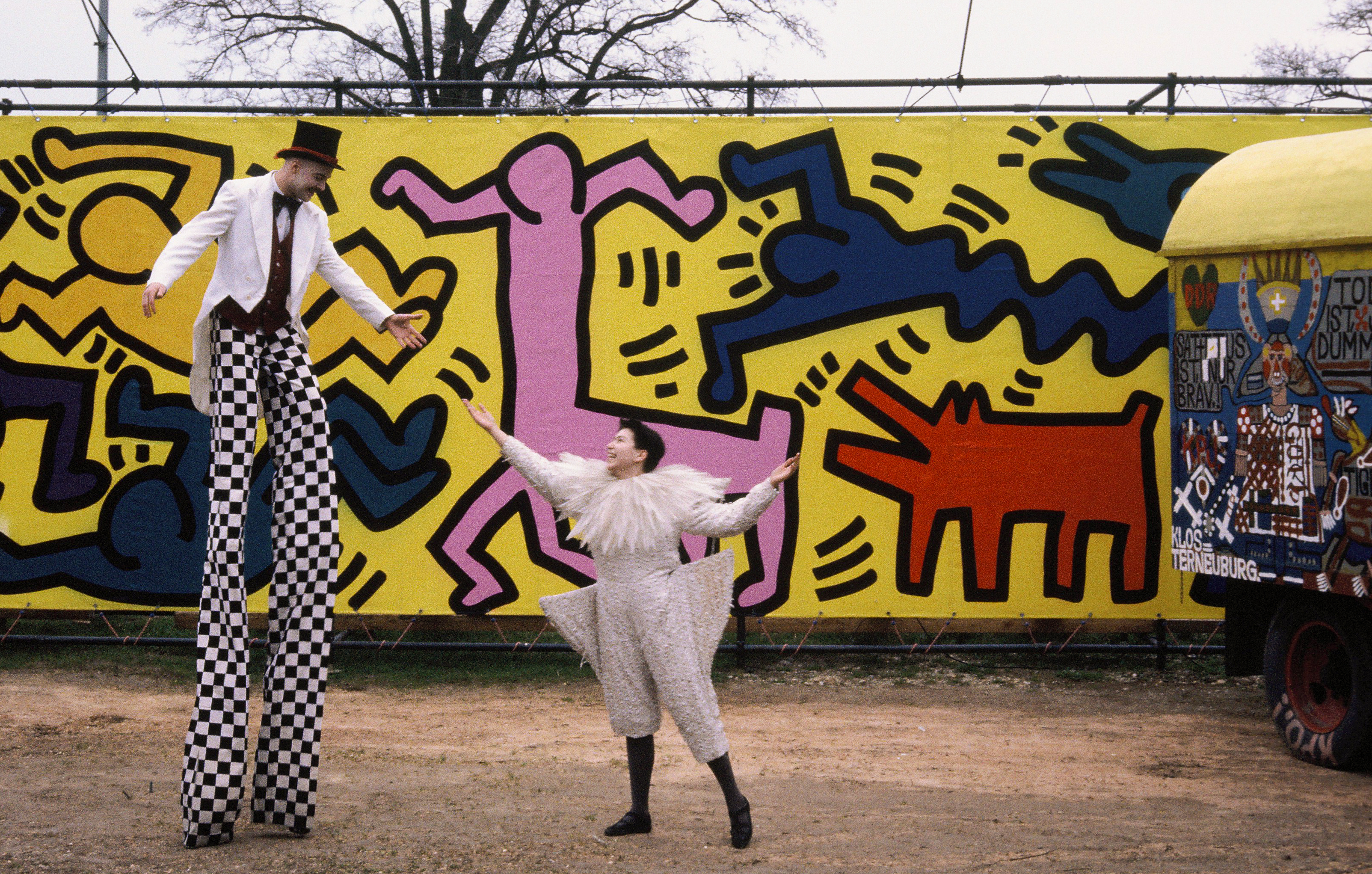

On a recent evening in Hudson Yards, a small carousel featured characters in quirky, Twister-like poses and an outstretched dog with seven legs. (Almost a century old, the rides are no longer rideable.) Goofy wooden sculptures were elevated in another corner, some of them cross-eyed or with a horn for a nose. A geodesic dome glowed, with Gregorian chants hovering somewhere above it.

"It's an art experience like no other," Michael Goldberg, Chief Experience Officer of Luna Luna, said recently. "People get to see artists do things they've never done before," he added.

Goldberg, founder of Something Special Studios, a creative agency behind many Nike campaigns, was determined to resurrect “Luna Luna” after reading about it online in 2019. Goldberg shopped for investors, eventually teaming up with DreamCrew, a media company co-owned by the rapper Drake. (Details on the company's investment remain vague; sources have reported that DreamCrew spent over "100 million dollars.") In 2022, an intensive restoration process began, with a team of artists reviving many of the original works, which had remained in boxes in a Texas warehouse for over thirty years. Several had been in pieces. (The team reportedly had to rebuild each work "bolt by bolt.")

That night, at the Shed, fourteen out of the original thirty-five works were on display, including the small carousel (Keith Haring), the goofy sculptures (Kenny Scharf), the neon dome (Salvador Dali), and a towering Ferris wheel decorated in drawings of stick figures, upside crowns, and references to Jim Crow (Basquiat). Missing works are in a "constant state of restoration," Goldberg said. Meanwhile, new attractions are joining the line-up. For the New York show, the Puerto Rican duo Poncilí Creación was commissioned to create "PonciliLand," a blink-and-you-miss-it section where guests "can create fantastical characters out of custom building blocks." Poncili also developed floating characters, inspired by performers who circulated the original “Luna Luna” fairgrounds in 1987. Known as "Lovers," the two characters, large and dreamlike, teetered to one side, mumbling the kind of nervous groans one does before a fall. (They never ended up falling.)

I asked Goldberg if, given that today's culture doesn't quite look or feel the same way as it did in 1987, there was any hesitation in showing some of the original works. On a back wall, a tribute featured Manfred Diex's "Palace of the Wind," a show featuring performers who fart into a microphone; on another, two ornate pedestals held sculptures of spiral poop.

"I don't see any reason why we wouldn't show any of these works," he said. "A lot of the time, art is exclusive and uninviting. The big difference between “Luna Luna” and other art experiences is that it has many sides to it, and things that have a bit of humor and playful energy. "As for "Palace of the Winds,” the decision to keep it was simple: farting is universal. He went on: "The “Crap Chancellery" is, conceptually, one of the most important works in “Luna Luna.” Daniel Spoerri's dad was killed in the Holocaust, and the work was inspired by Albert Speer, who was Hitler's architect. He took the facade of what was meant to be a Nazi shrine and turned it into the facade of a bathroom with two steaming statues of shit standing on the outside. These works are extremely important and are things that we would definitely want to honor and draw attention to."

As “Luna Luna” further develops, the show will likely change. "It will continue to evolve as we go to different cities in response to the spaces that we pop up into and in collaboration with the local city," Goldberg said." With it, there will be new characters and new stories to tell. One aspect that won't change, though, as Goldberg assured, is a long-held sentiment about a potential partnership. At one point, early on during the original “Luna Luna” era, McDonald's wanted to buy into it. Heller said no, adding that he "didn't want it to feel like Disneyland." Goldberg agreed. Nonetheless, as I watched Kenny Scharf's dizzying swing ride go around for what felt like the hundredth time, with the cartoon characters decorated on it blurring together (one with a villain's grin, another morphed into a martini glass), I couldn't help but feel like maybe I was at Disneyland, only not as robbed, but just as entertained and exhausted by its rides and fantastical characters, and wanting to go again.