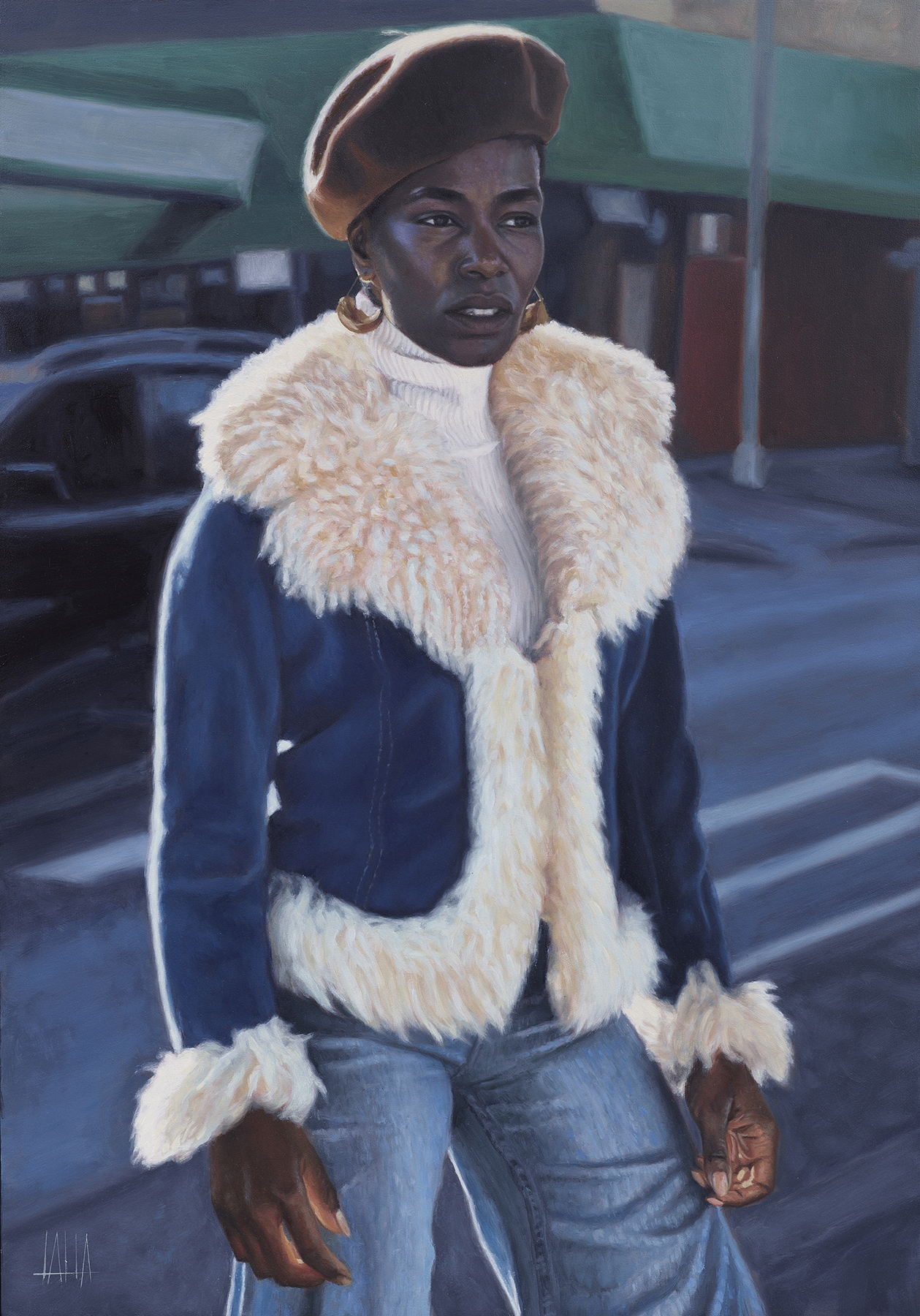

Collective Catharsis

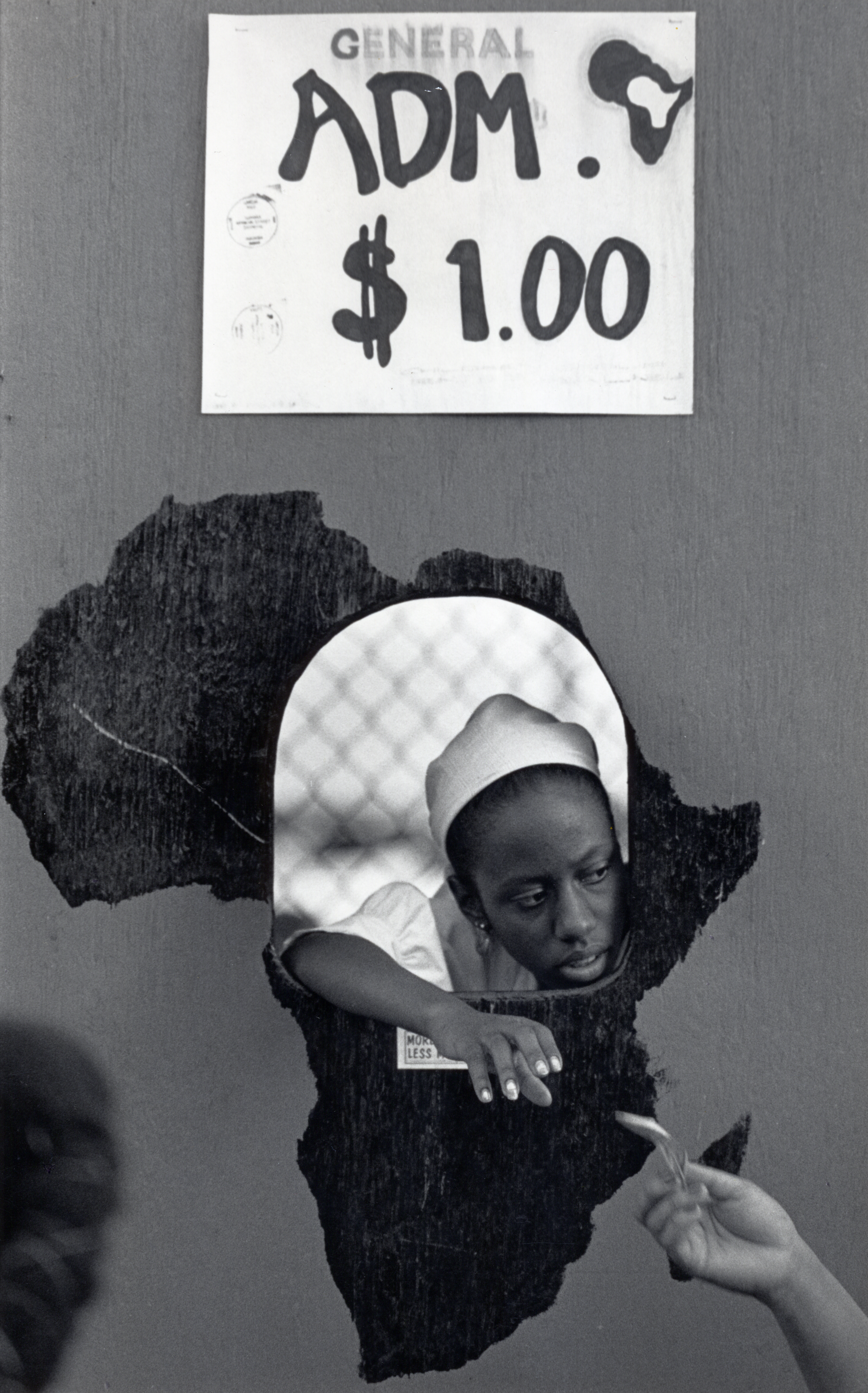

See some of our favorites from the fair, below.

Prizm Art Fair is open now through December 9 at Art Basel in Miami.

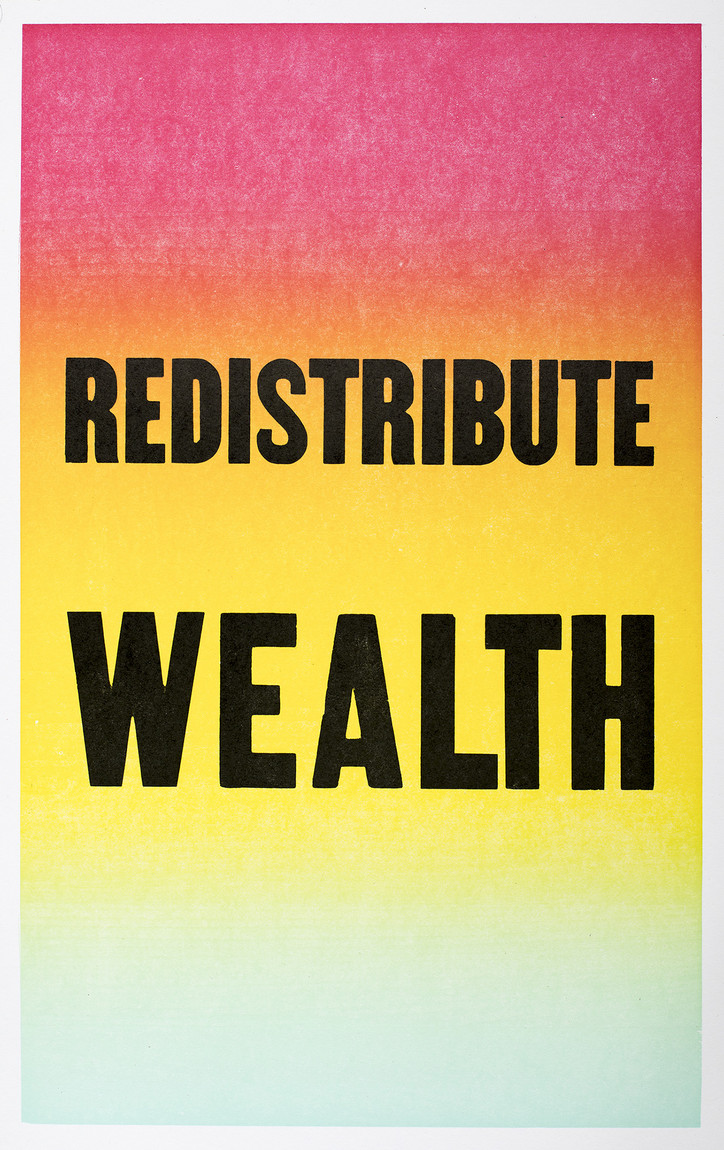

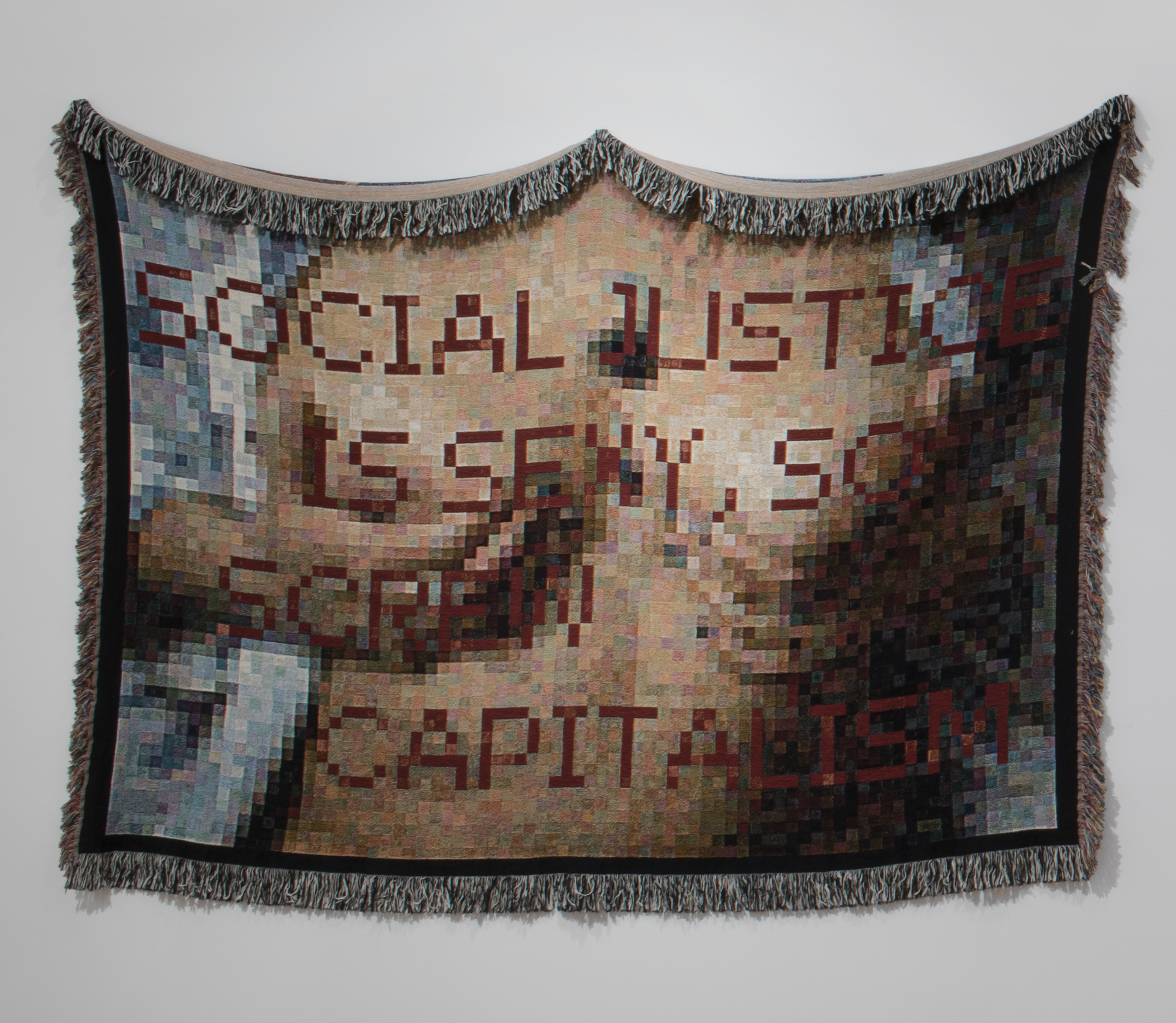

Lead image: Dread Scott, 'Redestribute Wealth,' 2018; all images courtesy of Prizm Art Fair.

Stay informed on our latest news!

See some of our favorites from the fair, below.

Prizm Art Fair is open now through December 9 at Art Basel in Miami.

Lead image: Dread Scott, 'Redestribute Wealth,' 2018; all images courtesy of Prizm Art Fair.

Referencing a Bad Brains song, which will be performed live during the show by musician Holland Andrews, the title of the piece — Voyage Into Infinity — captures the infinite potential of small actions and synchronicities, much like the domino effect at the heart of this performance. Like her belief in serendipity and the interconnectedness of events, Narcissister's process for this project involved scavenging found objects, allowing chance to guide her decisions. Andrews’ involvement blends experimental and punk elements, adding layers of meaning and energy to the work. This exploration of collapse — both literal and metaphorical — continues the artist's ongoing questioning of seemingly perpetual oppressive systems.

Ahead of the performance, Narcissister and I spoke about bringing the project to life. We bonded over our mutual belief in chance and serendipity, both its magical and scientific origins.

How was your Labor Day weekend?

I was able to relax a bit, which was nice, but mostly just staying focused on getting the show done.

Right, I can imagine. This is your first large-scale performance commission since 2012. It’s been a while, hasn’t it?

Yeah, though I've worked on other ambitious projects since then. I had a feature film that premiered at Sundance in 2018 [Narcissister Organ Player] and another short film in 2020 [Narcissister Breast Work] that premiered there too. So I’ve been working on large projects, but yes, this is my first large-scale commission since 2012, and it’s quite complex. It involves live music, pyrotechnics, other performers, and the installation itself is big so yeah, it’s quite ambitious.

It all sounds super exciting. One thing I wanted to ask is about your reference to The Way Things Go by Fischli and Weiss. Your reinterpretation of it, which I love, shifts from the original absence of actors to a performance with female-presenting performers. Can you talk about the intention behind this shift?

I've known about that film, or rather work of art, for a long time. It was a very early and potent source of inspiration for me because it stretched my ideas of what art could be.

I’ve always loved its aesthetic, ingenuity, simplicity, and the way it was captured. It felt dangerous, funny, and involved an incredible skillset, while still maintaining a sense of humility with its use of everyday objects. The space they used, this old unfinished loft, was inspiring too. It reminded me of the kinds of spaces artists used to have access to.

As a young artist, I was drawn to all of that. I had that skillset of wanting to know how things work and taking things apart to understand how they worked and putting them back together myself, so it resonated deeply. In adapting the piece, I was interested in making the performers integral to the workings of the machine. There’s something radical about having them be instrumental in the collision of these rough, found objects — many large-scale next to these female-presenting bodies. There’s also an idea that if a creator isn’t seen, we assume it’s a man. I wanted to play with that.

100%. That assumption is so ingrained, shaping how we perceive creators or works of art.

Yes, it's just one of those unspoken understandings that we don’t often question. When we don’t see the creator, especially in works like this, it’s easy to assume it was made by a man.

Yeah, and those ideas are so entrenched, similar to how we learn to recognize shapes and other simple concepts as kids so it becomes automatic. Your work challenges these assumptions. I recently interviewed a photographer who photographs drifters, and a very specific form of masculinity he grew up around in Paris, Texas. This led me to think about how identity and the masks we wear are central to your project. Has the role of the mask evolved for you?

The mask is a core part of my Narcissister project, and I’m committed to it for life. It’s not about changing or evolving it per se. The mask, modeled after a 60s-era wig form embodies a very specific beauty ideal coveted back then — with its wide-set eyes, pointy nose, and prim mouth. It’s this eerie, uncanny representation of femininity. I find it interesting to combine that mask with rough, found objects or large-scale materials. There’s something exciting about these seemingly disparate elements coming together.

It makes me think about 'Instagram Face,' a term coined by Jia Tolentino in a 2019 article for The New Yorker. Have you heard about that?

I really do my best to spend as little time on Instagram as possible so I haven’t heard of that, no. I finally created an Instagram account relatively recently because I felt that I was just self-sabotaging my career ambitions by not having one, but I resisted it as long as I could. Now, a friend of mine posts on my account, and I tell her what to post. I just really struggle with it as a value system.

No, that makes sense. So, Jia describes “Instagram Face” as a “cyborgian” look — a mix of social media filters, apps like Facetune and plastic surgery. It contrasts your mask being a very specific ideal from the '60s, which to me, speaks to how our ideas of beauty change over time but remain, essentially, the same.

Oh, totally. That’s absolutely true and it's fascinating, but also dark, how these oppressive notions find new ways to infiltrate, regardless of the era or medium.

Yeah, and we’re seeing real-world consequences, where people bring photos of themselves with filters to plastic surgeons as reference points. Do you ever think about how the ability to change or modify our faces, literally adopting a mask, has evolved?

I think it’s something we can all relate to. We all experience some kind of discomfort with how we look. I think what happens with myself, and most of us, is a voice of critique when we behold ourselves in the mirror. We can all continue to do work to accept and love ourselves and to genuinely see the person reflected in the mirror and I think we can all relate to this idea of wanting to change or modify how we look and most of us do in some way or another — whether through makeup, hair dye, surgical modification.

My strategy with the mask is to remove my actual face from the work, making the art not about me, but about broader issues. I also just want to keep myself private and the mask is just much more interesting — it comments on all the things we’re talking about, especially these beauty standards and the impossibility of meeting them. And as I age, I think it’ll become even more interesting — the mask will stay the same, while my body changes.

That contrast is so interesting, especially with the inevitability of aging. It reminds me of the concept of collapse, which you also explore in your work. From 2012 — with its doomsday craze — to now, the world has changed so much, especially with climate change and conflict. It feels like we’re closer to the edge. Your piece is titled Voyage into Infinity, which seems fitting. How does that title resonate with where we are now?

Yeah it’s funny, I almost forgot about that. I remember the Y2K idea. I wasn’t thinking about that specifically, but the idea of the Rube Goldberg machine as a literal domino effect is central to the work. In many ways, that’s what life feels like — a series of small actions that ripple outward. Even in the face of the current state of the world, I think there’s power in small gestures. The title, Voyage into Infinity, reflects those ongoing themes I’ve always explored — race, gender, eroticism, womanhood, and identity. And as I get older, aging becomes a more prominent angle in my work. While this particular piece doesn’t overtly focus on aging, it’s present.

That’s a great point. I’m also thinking about how our collective understanding of issues like race, gender, and identity has evolved since 2012. The conversations have changed so much.

Oh yeah. For sure. It’s been a dramatic shift.

Diversity isn’t just about acceptance anymore, if it ever was — it’s about expanding the consumer base. And it's difficult to grapple with because yes, I as a person of color do want to see diversity, but there’s something also somewhat insidious about it.

Yeah, I know. It’s challenging. On one hand we like to see ourselves reflected more fully in the world — in ads, movies, and other platforms. As a person of color, it feels exciting and validating to see people who look like me or my family reflected. But then there is what you're saying, this insidious idea that often diversity is just used as a tool to sell something, or more recently, since 2020, it’s this complicated thing about how much of it is performative? Do these brands actually care about diversity or is it just that they need to seem like they do?

And then it’s like we’re all part of a system like instruments in a machine. Your performers are literal instruments in this piece, right?

I mean, yes sure, we can take that route but that’s so dystopic and I like to think we have way more agency than that. It’s our role to wake up and be conscious and to excuse ourselves from these machines that are doing their very best to co-opt us. There are these beauty ideals, the achievement of eternal youth, the unattainable through what we consume, but then we also do have a choice.

My performers in this piece aren’t just passive instruments — they know how the machine works, they control it, they decide when to trigger it. The machine doesn’t work without them. That’s a key distinction.

That makes sense. This idea of choice, even within the systems that co-opt us.

Yes, and that’s so essential. And I feel like we all have that choice on some level if we're willing to put in the effort to claim it.

That’s a powerful idea. And thank you for explaining that. I’m also curious about how you balance your own identity with Narcissister. The mask keeps you private, but the work has its own identity. It reminds me of how an artist’s identity can sometimes overshadow their work. How do you navigate that?

That’s always been really important to me. My personal experiences inform the work, but I don’t want the work to be about me. That’s why, from the inception of this work, I knew I’d wear a mask. I started Narcissister when social media was really growing in popularity, like 2006, 2007. What was the thing before Facebook?

MySpace?

Yeah that’s it. Suddenly we could create online profiles about ourselves and it became so easy to take selfies — or self-portraits. Obviously, that’s something that’s always occurred in art history, but now it's so instantaneous with our devices that suddenly there were all these portraits of everybody everywhere just doing random, mundane things. I was never personally interested in participating in social media and the mask was a way to comment on these tendencies while keeping my identity private.

It’s interesting how your mask plays with the idea of collapsing identities, especially in a world where social media is constantly bombarding us. We produce and consume content so quickly today. Does that affect the pace at which you create your work?

Well, I don’t see my project as a reflection of everything in society, but it is a reflection of beauty standards for example, particularly for women. My work isn’t technology-based. It focuses on the body, movement, identity, and crafting with your hands — elements I consider timeless.

My work often incorporates the human body, nudity, orifices, and movement — these will always remain relevant. Eroticism, aging, the body’s capabilities — these are fundamental. Even with today’s efforts to slow aging or extend life, it’s still about the body and what it can do. There’s a kind of everyday narcissism that has become more prevalent with the rise of social media platforms, and my project also comments on that.

Dance and movement are also essential to my practice, and I don’t see those things changing. And I still sew my costumes on my mother’s Kenmore sewing machine from the 1970s, which is what we do everyday anyways — we wear costumes. That’s not going to go away. These questions of identity are going to shift over time,l think they’ll never be irrelevant, but only time will tell.

That’s refreshing to hear and what I believe makes your project stand out. I also wanted to ask about the music in this performance — Holland Andrews is composing the live score, right?

Yeah, I’m super honored that they were interested in being part of the piece. I really trust Holland. They’ve been incredibly intuitive in capturing the tone of the piece. The score has two parts — an experimental section for the first half, and then it shifts to punk for the second half. I’m excited about that energy shift in the show and the layers of meaning tied to Holland singing this Bad Brains song, "Voyage to Infinity". I think it’ll be really meaningful and a strong moment.

I’m excited to see how the music contributes to the atmosphere. And Pioneer Works seems like the perfect space for this. What’s it been like working in that space?

Oh, I mean, it's so incredible. It's one of the most amazing canvases that an artist can be given. Just the vastness of it, the aesthetics of it, and even the history of it. For me, it feels very fitting to make a Rube Goldberg type machine in that space. There’s just so many possibilities. When I pitched this project to Gabe, the curator, I just knew that it would just be perfect for that environment.

Are possibility and chance central to your process?

Yeah, especially with this project. I had a list of ideas for effects I wanted to create, but as I worked, I realized I needed to add new elements to connect them. I also used all found objects, so the materials I found influenced the final outcome. Being a scavenger is so central to the project, and I feel like I always find what I need. It’s always been that way for me. I find the elements that I need and that determines what the piece is going to be.

Do you believe in synchronicity?

100%. When I’m laying in the bath at night, I listen to New Age speakers on YouTube. I love all that stuff. I also listen to NPR a lot and I remember this one show that was all about coincidence. They shared different stories like this about someone going to Sweden for a wedding (their best friend from college married a Swedish person), and while they were there for only two nights, they randomly ran into an ex-partner from another part of their life, who had no connection to the wedding.

It got into the idea of mathematical equations and probability, how these chance encounters could be explained mathematically. I can’t remember all the details, but it really shook me because it's exciting to think about that. I love believing in magic and serendipity, in the idea that we encounter people or things for some kind of divine reason.

At the same time, it’s also exciting to think that there’s something empirical and rational behind it. I find both explanations liberating, and neither feels alienating. Like you said, it ties into waking up and having agency. I strongly believe in our ability to manifest things. We have the power to create things for ourselves, whether it’s positive or negative.

That’s incredible. I’ve had experiences like that. It ties back to the domino effect you mentioned earlier. I always think about that. My guilty pleasure is watching Jordan Peterson’s lectures on Carl Jung from years ago and he talks a lot about serendipity. What is the experience of seeing yourself wearing the Narcissister mask?

Internally, I love it. It’s one of the reasons I’ve committed to this project indefinitely. I love diving deep into the character and embodying the character. There’s something primal and childlike about it — it feels like play. I get to explore different aspects of identity: sometimes I’m a man, sometimes a woman, sometimes a little girl, or an old lady. There's freedom in that. It’s playful, but not in a frivolous way — it’s about exploring identity through movement. I’ve always loved moving my body, ever since I was a kid in a movement class, where we were invited to move intuitively and it was just so wonderful for me. It just feels very fertile.

As for wearing the mask, I’m somehow comfortable with not seeing well or not being able to breathe well. It doesn’t feel suffocating to me. But when I see myself from the outside, there’s a layer of complexity. It ties back to what we talked about earlier — the desire to escape into a different identity. When I look at myself in the mask, it’s sometimes practical — like adjusting the wig or costume — but there’s also satisfaction in obliterating my identity for a moment. It’s like what people feel on Halloween when they get to be something they’ve always wanted to be.

With Narcissister, would you say that the project exists in a state of becoming? There’s always this in-between moment, right? The audience knows you’re wearing a mask, but they don’t know who’s underneath and likely won’t be present for the moment you remove it.

I imagine part of the fascination and appeal of the project is people knowing that there is a person underneath the mask that they wish they could see, and people wonder if they’ll get to see them. They’re waiting for that moment when the mask might come off, but it doesn’t.

Totally. I wanted to ask about translating the performance into video — how do you capture that immediacy in a recorded format?

From the start of Narcissister, I made art videos of my performances because I wanted the audience to see details that might be missed on stage. Whether it’s the handmade elements, like the sewn breaks in the costumes, or the lines where I’ve cut the mask, I wanted those to be visible. Video allows for that close-up experience and lets more people experience the work. It becomes something different in video, but equally strong.

The video is going to be a straightforward capture of the show — unlike my art videos — and it was important to Gabe and me to make this video, especially since the reference piece, The Way Things Go, only exists as a video. It’s a performance, a sculpture, an installation — all captured in video form.

Speaking of Gabe, what was it like working with him to bring this project to life?

It's been great. I’ve attended events at Pioneer Works here and there over the years, and I saw a show by Kembra Pfahler, who I’ve known for a while. I feel connected to her lineage of work and thought, if they’re presenting her work, maybe they’d consider mine. It was one of those moments where, as an artist, you have to be willing to network. After her show, I introduced myself to Gabe, the curator, and told him about Narcissister. He hadn’t heard of it, so I asked if I could send him some links. He gave me his info, and after a few months, he reviewed the materials and responded. Now here we are.

Talk about synchronicity. I love knowing that you manifested this.

I feel really good about the fact that I created this opportunity for myself. Gabe didn’t know me before, but I introduced my work, and it resonated. That doesn’t always happen.

And his feedback has been spot on. Sometimes working with curators can be tough because their feedback feels out of left field, but Gabe really understands this kind of project. He’s given helpful guidance without being heavy-handed, which I appreciate. He’s left me a lot of space to create it myself.

Centering around themes of desire, consumption and the body, the season featured three showcases: paintings and sculptures by Hanna Rochereau, photography by duo Chaumont-Zaerpour (Agathe Zaerpour and Philippine Chaumont) and a series of short films by director and editor Lucia Martinez Garcia.

“The art scene in Biarritz is definitely growing, and we're thrilled to be part of it,” continues Christie. “The town’s blend of historic charm and tourist appeal makes it a perfect place for this kind of project. We’re using our international experience to meet the rising demand for diverse cultural offerings. We’re planning for both busy times and quieter moments to keep things balanced and interesting.”

Read on as office’s Paris and Biarritz-based Editor-At-Large Paige Silveria has a brief chat with everyone.

Paige Silveria— Tell me about the show, "Everything Not Saved Will Be Lost." It looks like it was intentionally created for the gallery space.

Hanna Rochereau— I’ve always wanted to make a show that adapts to a specific space and this was the first time I was really able to do it. I’ve been able to plan and work on it for about a year. This gallery is so interesting — it really allowed me to create a concept that was theatrical, something that’s not very easy to do within a white cube. It was really important for me to fit into the space, especially when considering the color and the materials I chose. For instance, all of the frames I made myself to match the existing framing on the walls.

PS— Can you give me more background on your organizing concept?

HR— I intentionally create a kind of tension between what is visible and what is hidden, which ties into the exhibition title. The idea is about reversing roles, where the display itself becomes the object presented as luxury, while the "purchasable" object disappears. I’m super interested in window displays, behind-the-scenes storage areas, the framing that is created for the products, the boxes and wrapping. My work is all about desire and desiring objects, and the frameworks that help to create that desire in the consumer. I love to play with what is missing in the space and shift the focus to these frameworks. A lot of my paintings are linked to the fashion world. There will be several collections each year, so quickly, and so much consumption is generated. So while my subject is all about this fast-paced world, for me as a painter, my process is very slow — digesting the concept and creating the artworks.

Paige Silveria— Tell me about creating your exhibition, “Points of Sale.”

Chaumont-Zaerpour (Agathe Zaerpour and Philippine Chaumont)— When Marie and Christie suggested we do an exhibition in that space, we immediately thought of a project that would engage with the architecture. It's a very bourgeois environment, and we thought it would be interesting to display something reminiscent of a boutique, but in an irreverent way. Recently we've been very interested in exploring the imprint of fashion imagery on our intimate relationship to clothing. The construction of fashion images relies on a set of codes, the mastery of which keeps those who create them in an illusion of superiority, while ignorance of these codes excludes the intended audience.

In “Points of Sale,” we cropped and enlarged pretty brutally some archives from our editorial and commercial projects, to form a naive and linear inventory of anonymous feet displaying their shoes. We wanted to reduce the status of the photographs from which they are extracted to their essential advertising triviality. Arranged in a continuous line, they highlight the perpetual metamorphosis: these codes that we create and that, in turn, transform us. The images themselves have a dusty feeling from being re-photographed, enlarging the print raster of the magazine they come from or the grain of the film. They are printed on a very thin and yellowish paper that feels like big pieces of old newspaper, hung on the walls with tiny pieces of paper tape: when the high windows are open, they float like spirits haunting the place.

PS— What kinds of projects do you love to do and why?

CZ— We have a great time working on both our commercial and artistic projects. We always worked in a way where both are really connected. Recently we've made much more space for our personal work, and it often is a comment on our work as fashion photographers. So each part really nourishes the other. A lot of our images start from references to the history of photography and its acceptance as an artistic medium. We've also always felt very drawn to vintage fashion imagery, and earlier aesthetic codes in general, iconic advertising campaigns, women’s magazines from the 60s, 70s, 80s and to classic photography. We try to use the language of fetishism that underlies these references and to subvert it to the point of absurdity. Having studied graphic design and worked in the publishing world before photography, we attach a great deal of importance to the relationship between images and the resulting narrative. The final form of our images is most times a layout or a sequence, and we have a hard time considering each image on its own. So we love storyboarding our stories meticulously: we usually draw each spread we're going to shoot, and determine in advance where each image will be in the layout. So we're quite organized when we shoot. We usually get more experimental in the editing process. And being the two of us makes every part of the process really exciting. It's so helpful bouncing ideas together, and so reassuring to be able to navigate that industry being around your best friend at all times.

Paige Silveria— The films that were screened with La Fonda were absolutely heartbreaking. Can you explain the recurring focus and themes throughout your work?

Lucia Martinez Garcia— I’m interested in portraits, particularly of women. When a person transmits emotions to me, I want to film them and showcase their beauty and fragility. I like to make films infused with both poetry and violence. My characters are often filmed at stages of their lives where they’re lost, searching for themselves; where they are vulnerable and, at the same time, we perceive their strength and dignity. I try to capture the unspeakable.

PS— What's the process like of locating, casting and working with non-professional actors? Why do you prefer to hire with them?

LMG— Apart from my last film “Blue Light,” I wrote all my projects knowing who the actor was going to be. I draw inspiration from their personalities, from the experiences of those around me, and I stage it in situations that I imagine. For "Blue Light", it's different, because I wanted to experiment with other things: 16MM, having a person I don't know play, creating narration without words, etc. For “I’m the only one I wanna see,” [described as “A woman, a dancer, a creature, dances, free. She laughs at the violence, the insults, the looks that reign around her."] even if the film is not inspired by the actress, I knew her way of dancing and the abilities she had. She’s a very good friend, Léo Chalié, who played in my first films, and she became an actress afterwards. Now she plays in series and feature films, but I know she always wants to experiment with new things, and with this film, it was an opportunity to do so.

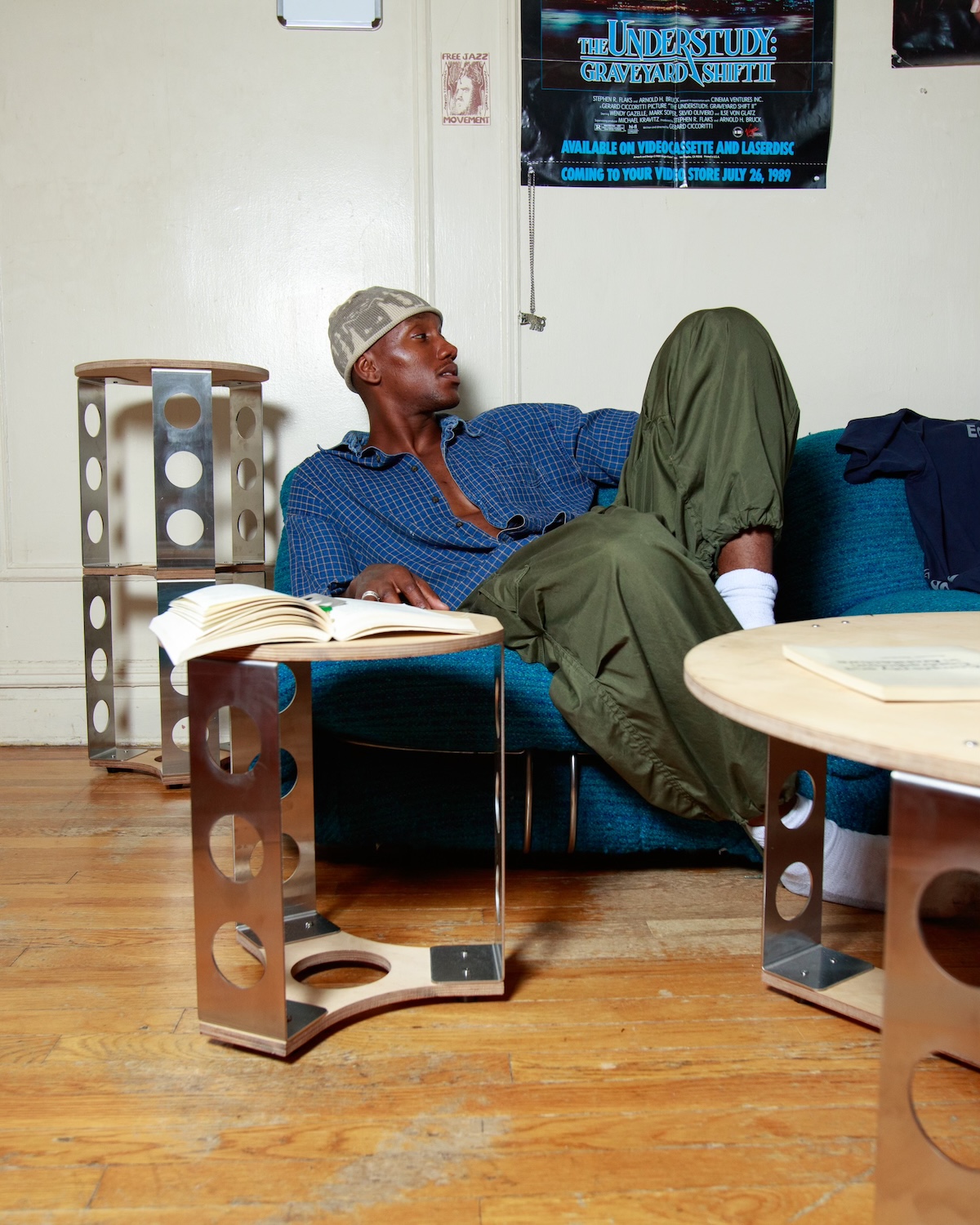

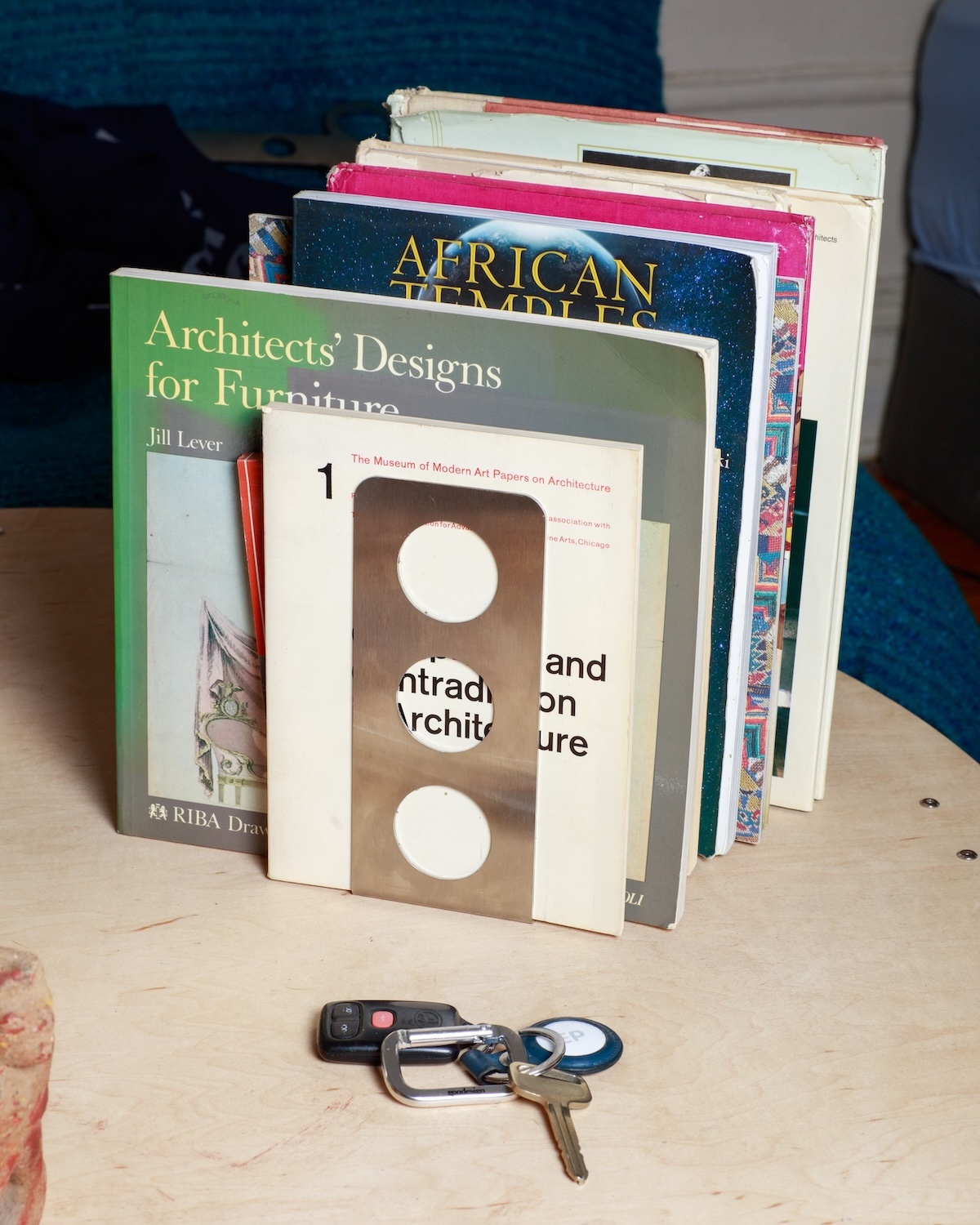

Popoteur debuted the Eclipse System at goodesign’s inaugural event at Awake's LES storefront, showcasing the set's versatility by building stools, coffee tables, dining tables, and even clothing hangers. The space also featured a curated collection of books by Storagebased, while a Christian Tokyo DJ set and Solomon Gottfried’s jazz quintet performed atop various pieces of goodesign furniture. For Popoteur, a Washington Heights native known for his innovative spirit, the event marked a significant milestone. He first made waves in the furniture world with his PVC pipe-constructed chair, which not only caught attention but also set the tone for his creative ethos: making the extraordinary from the ordinary — a philosophy that's clearly embedded in the DNA of the Eclipse System.