The Creatives of Tbilisi Fueling The City’s Renaissance

In the years following their break from Soviet control, Georgia has been eager to establish its place in the greater cultural conversation. It is no surprise that a country filled with a history of deeply-rooted tradition has no shortage of creativity — the artists and designers that reside in the bohemian city of Tbilisi are what give it its grit and character, and also its sense of community. A country that has four customs catalogued in UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage listing is proof enough — their tradition of polyphonic singing makes beautifully-harmonized singing as ubiquitous at dinner parties as drinking wine (which they also are credited with inventing over 8,000 years ago). Thus, poetic tendencies and an appreciation for beauty, is in the DNA.

For the many years under Soviet control, Georgia’s connection to the outside world was quite limited — the lack of outside influence allowing for its own unique identity to prosper. In recent years, the creative scene in Tbilisi has flourished, with a few key figures determined to make up for lost time, putting Georgia rightfully on the map in terms of art and culture. Through a myriad of public art programs, residencies that invite international artists and writers to spend time in the capital, and galleries that highlight Georgian artists, the artists and creatives of Tbilisi are eager to create a legacy for Georgia that cements a permanent place in art history and culture.

Max Machaidze

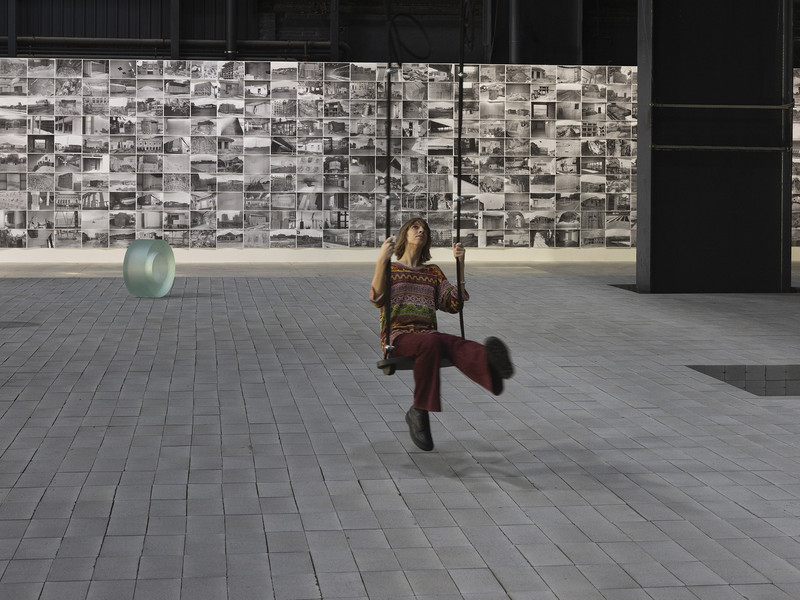

Max Machaidze is the king of the block. The D-Block, that is, Tbilisi’s Stamba Hotel’s in-house artist studios and residency program. A visual artist, designer and hip-hop musician, Machaidze creates large-scale sculptural work that can be seen installed throughout the grounds of the expansive hotel grounds. With his studio also located in Stamba’s D-Block, an undeveloped wing of the hotel that has been converted into two floors of open-plan artist studios, the proximity of his workspace seems to aid his prolific practice.

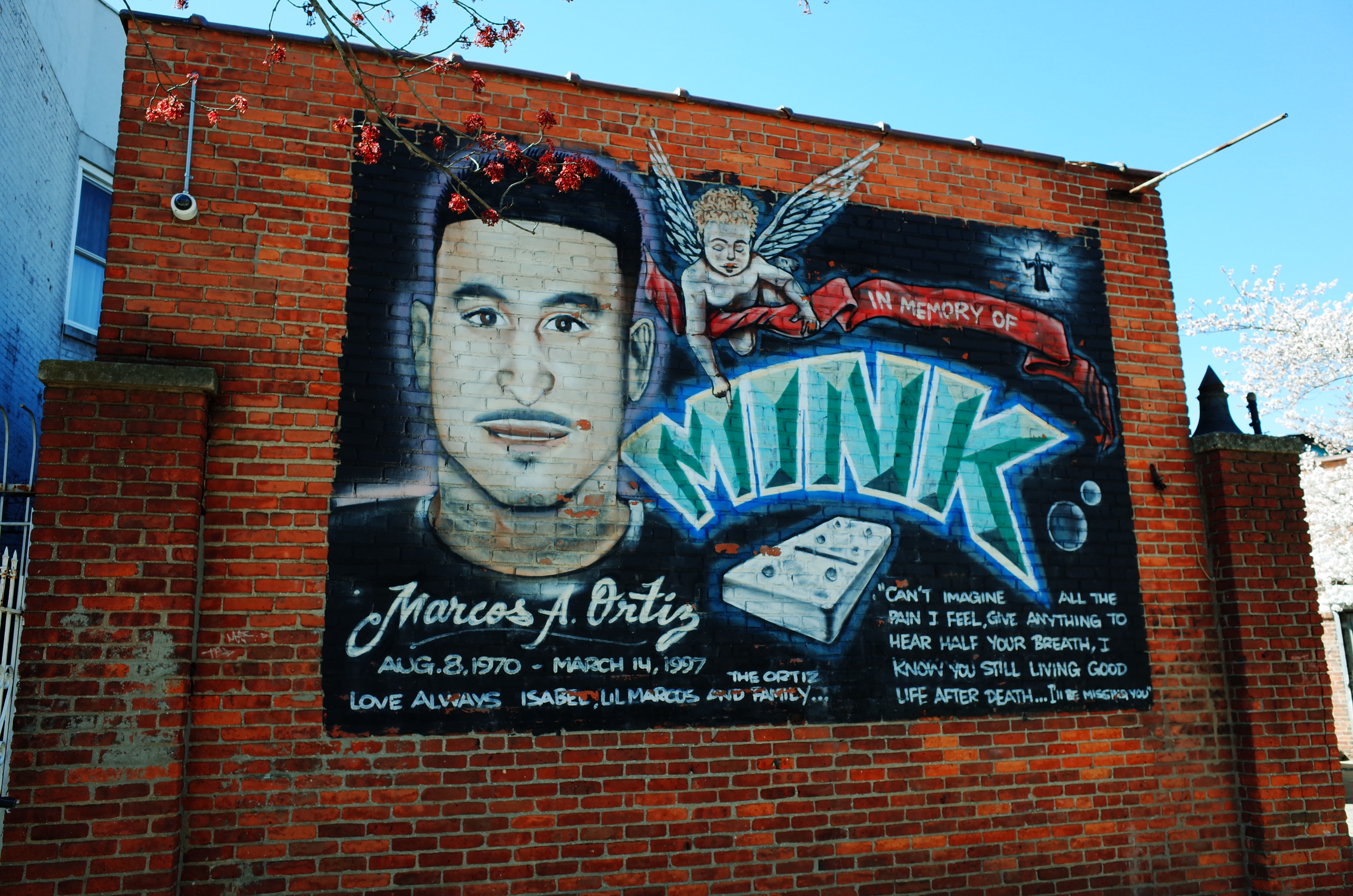

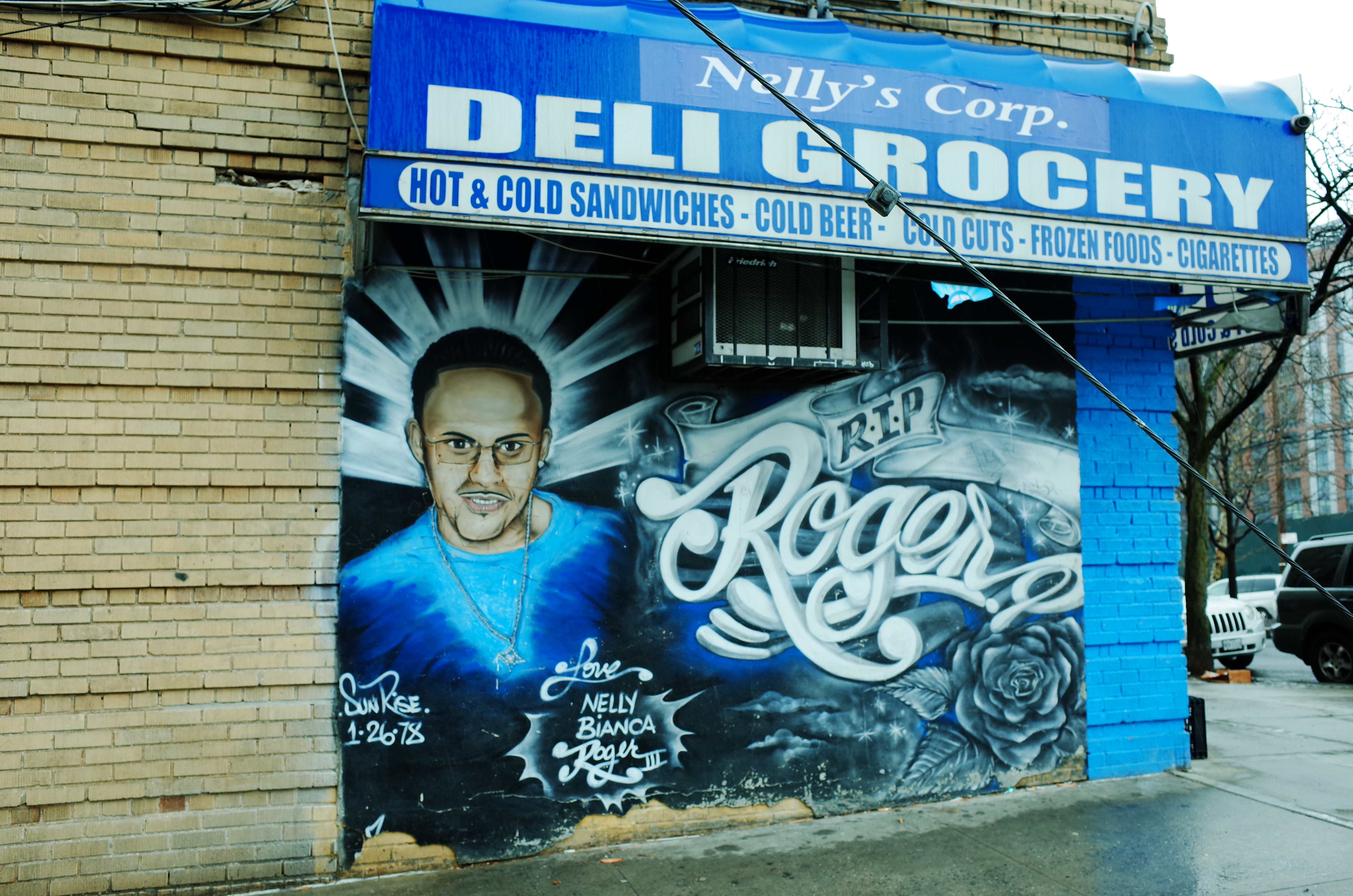

Producing works that range from massive cement spirals that sit in the hotel’s courtyard, to a fully-functioning replica of a ‘90s ATM so realistic it blurs the lines between art and utilitarian object, Machaidze draws on found ephemera and Soviet remnants from the country’s fraught past. Sourcing found objects as the basis for his materials, Machaidze frequents abandoned auto-body shops for sheet metal, which he then spray-paints with his namesake designs that echo his background in skateboarding and graffiti.

A longtime fixture at Stamba, Machaidze urged the Adjara Hotel Group’s owner, Temur Ugulava, to reserve the section of the building for creative output, rather than transforming it into commercial property. Described as a creative mastermind in his own right, Ugulava is a significant supporter of Georgian contemporary art, and took to Machaidze’s idea to use the area as “experimental space and artist studios.”

Not one to define himself by any one medium, if by day Machaidze is an artist and entrepreneur who started his own moped-sharing business called Qari, by night he plays sold-out shows under the moniker KayaKata, rapping a dizzying rhythm of melodic hip-hop beats sung in his native Georgian. When I ask how his myriad of projects come together, he tells me simply, “Whether it’s objects, sounds or words, it’s all poetry.”

David Meskhi

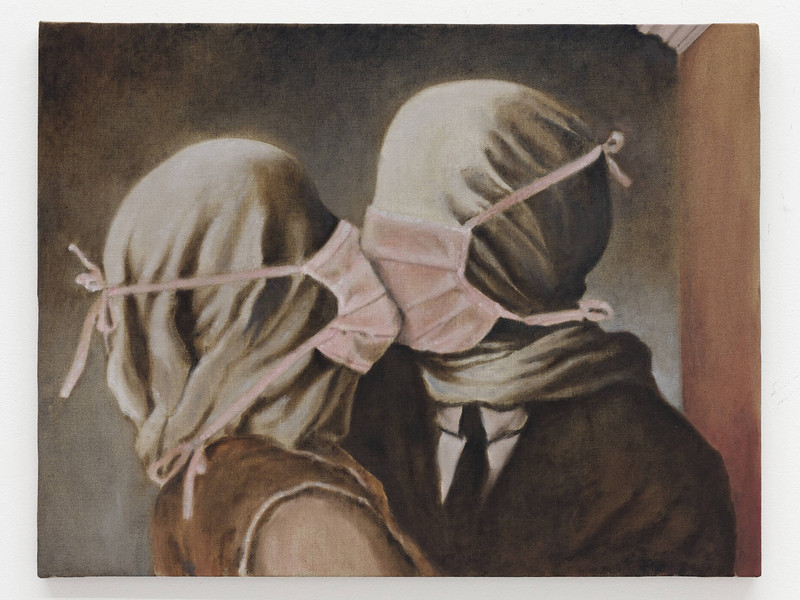

Conveniently located down the hall from the D-Block is the Tbilisi Photography & Multimedia Museum, a contemporary art institution in which Georgian photographer David Meskhi has a solo exhibition of recent works. Titled “Color of Weightlessness,” the photographic series depicts gymnasts in motion, reducing the human figure to abstract forms that seem to float like celestial beings. An exploration of the idealized body, Meskhi’s images confront identity, gender and even the country’s conservatism toward nudity by presenting the body as ethereal objects free from societal judgement. The cosmos is something that Meskhi has always been drawn to — this body of work contrasts Meskhi’s abstractions of the body with images of stars in space to create a shared language between the two otherwise unrelated subjects.

Raised by his father (a gymnastics coach for Georgia’s national team), Meskhi grew up around the sport — his childhood was spent on trampolines, which is the starting point for the exhibition. He developed this concept further, photographing athletes suspended in space, as a way to capture the feeling of weightlessness he remembers from childhood. In a format that makes the images look surreal, viewers lose sense of both time and place when looking at Meskhi’s work. It is within this void that Meskhi captures the duality of earthly and otherworldly.

Known for his early work shooting the skateboarding community in his native Tbilisi, his documentary, “When the Earth Seems Light,“ won various awards for its non-traditional portrayal of skaters. Interested in documenting the city around him, he noticed that the skateboarders in Tbilisi had the same acrobatic element as the gymnasts he started his career shooting. He began capturing them in a way that focused more attention on figuration and abstraction than the sport itself.

Now a photography professor himself, he tells his students, “it doesn’t matter what you shoot, you should be free to talk about any topic you want.” For Meskhi, the verticality one achieves on a trampoline is a metaphor akin to reaching for dreams of freedom. Stemming from a post-Soviet past both he and the country are eager to shake off, it seems that the higher you jump, the further you go.

Tamuna Gvaberidze

Gallerist and design consultant Tamuna Gvaberidze is on a mission to support Georgian art and give it the recognition it rightfully deserves. Her gallery, Window Project, began in an empty window at the Shalikashvili Pantomime Theatre in 2013 with fellow curator Irena Popiashvili. In 2019, she joined forces with a new partner Tamuna Arshba, and moved Window Project to a large, white-walled exhibition space in the stylish Vera district of Tbilisi. With a sincere dedication to supporting young Georgian artists while highlighting older ones from a “forgotten” generation, Gvaberidze’s goal is to use the gallery space as a platform for creative expression, providing these artists with the opportunity to show on an international scale. As a self-described “project-first” gallery, Gvaberidze is hesitant to claim ownership or exclusive representation over any artist she works with, believing that “collaboration and transparency” are crucial in artist-gallery relationships.

If there’s one quality Georgian artists share, it’s a sense of resourcefulness, Gvaberidze explains. “There’s a lack of materials here. They use whatever they have in order to make art.” Working within these constraints makes the artwork that is produced here analogous to the country itself, with many artists drawing inspiration from Georgia’s deeply rooted cultural traditions. For example, artist Uta Bekaia (whose studio is also at Stamba’s D-Block) creates wearable sculpture and performance-based pieces, borrowing from Georgia’s long history of tapestry and carpet weaving. His recent exhibition at Window Project includes an assortment of lifesize monster-like sculptures that take a page out of “Where the Wild Things Are.” Referencing a “post-apocalyptic world,” Bekaia makes a commentary on where the state of our universe is heading, by dreaming up how creatures may look in the future, giving them exteriors with unnaturally-bright colors and glitter.

Furthering her desire to create an international exchange between Georgia’s art and design scene and the rest of the world, Gvaberidze is expanding her gallery repertoire to launch the Tbilisi Design Days, a three-day international design conference set to debut in 2023. Working alongside architect Ketuna Kruashvili, Gvaberidze hopes to shine a light on the importance of art and architecture in Georgia. The duo, in turn, also hopes to gently nudge governmental agencies to provide more resources and funding for the arts. “We want to ensure that old techniques of Georgian craftsmanship don’t die,” she says. After 70 years of Soviet rule, Gvaberidze believes Georgian culture deserves as much recognition, both locally and internationally, as possible. “We are very expressive. We go deeper into our culture — it’s very old, diversified and polyphonic, like our music.”