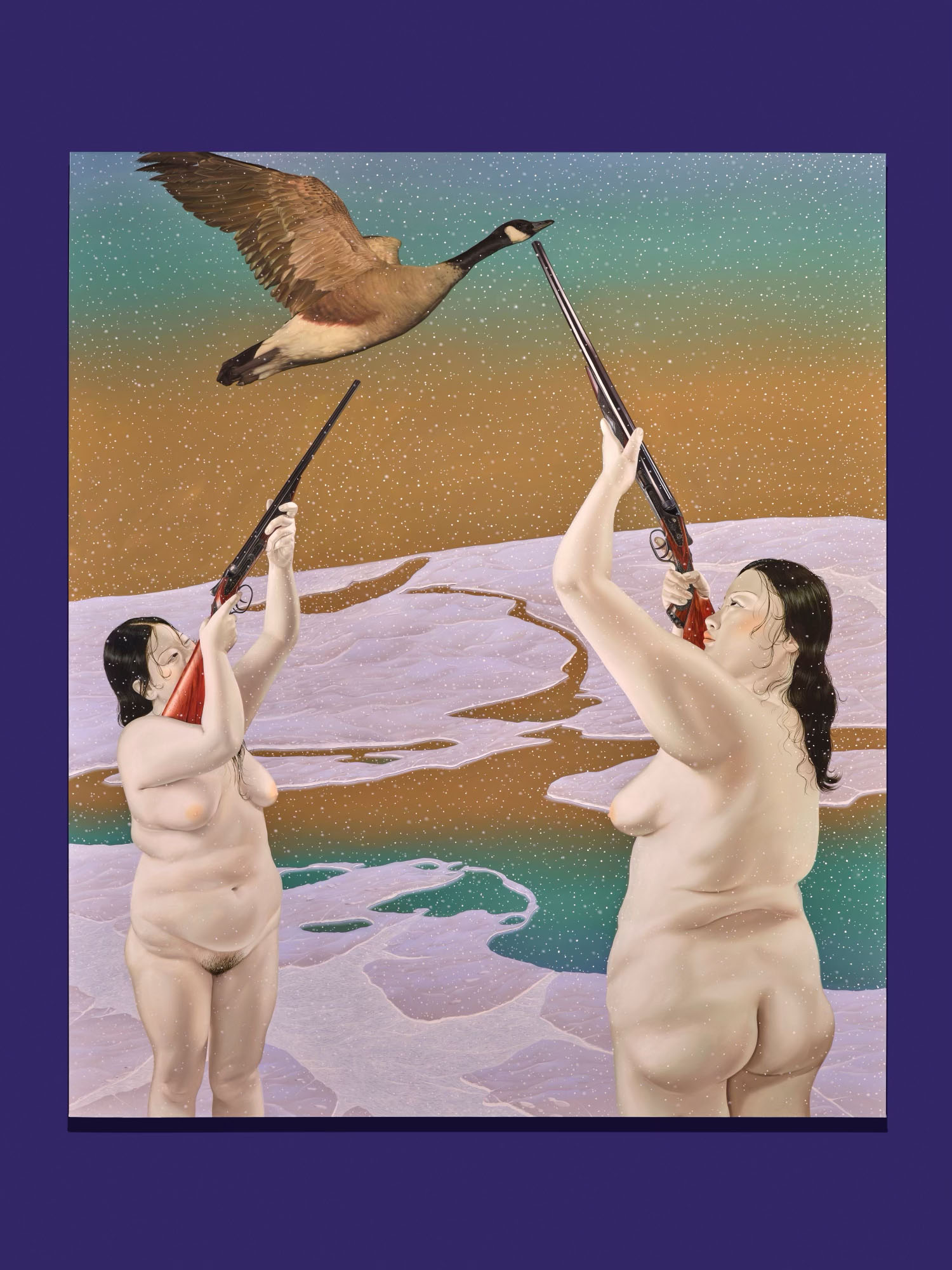

Catalina Ouyang Brank, 2024

True recuperation is also impossible. It was maybe 10 years ago that we suffered through that trend of revisionist Hollywood films like Maleficent with Angelina Jolie, Snow White and the Huntsman with Kristen Stewart, and other stories that tried to instate humanizing origin stories for classic villains and peripheral characters. That was something that I was once interested in in my work as well — the humanity and motivation of historically vilified women or Othered and queer characters. But in hindsight, I find that even in those revisionist narratives, the villain is sanitized into a misunderstood being of kind, good, or justified intention, and I'm more interested in, as we've been talking about, the miasma that exceeds morality or redemption. More like Angela Carter.

Even the desires that are foundational to our living drive — of accumulation, maintenance, and community building — are necessarily concurrent with the impulses of the death drive, which include pleasure, compulsion, individuality, and libidinal fixation. You have to find a way for them to coexist, which I think is what I am always trying to be attentive to in the signposts that I create with decontextualized references to historical figures, poems, and myths. My intention specifically is not to explain the gaps between them and rather to let them be generative in their unruly junctures.

How do the living and death drives show up in your work?

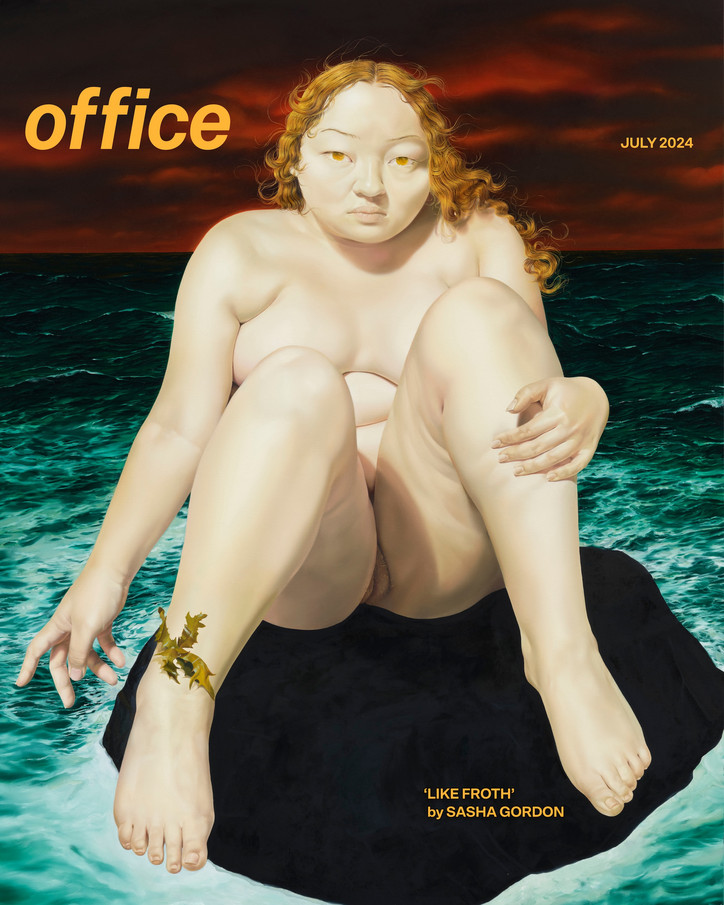

I think contradiction remains the word. With my invocation of the famous artist and courtesan Sarah Bernhardt, I am trying to address the act of selling sex as both an empowering, liberating mode of making a living, and also a survival industry that has trapped, extracted from, and killed many providers. Sarah Bernhardt is an iconic example of someone for whom it allegedly worked out. But there's also a lot of antagonism in my relationship to that kind of work and value-making. Part of my impulse to show paintings in this exhibition reflects how I feel similarly in some ways about painting as I do about my sexuality; it is this asset I possess that can be deployed toward some kind of value exchange that is efficient, but is in conflict with the fact that I want to make objects, I want to make conceptual work. I want to share my life with a lover and be loved without the raw threat of my sexuality and line of work getting in the way.

There are things that painting takes for granted — the picture plane, materiality, a painting’s objecthood or lack thereof — that I take issue with. There are things that my commodification as a sexual being takes for granted, that I most certainly take issue with. There are concessions at play, but still I am intent on engaging with the practices of making paintings and selling sex in honest, risk-taking, and challenging ways. So it's about going into the thing that already feels doomed, but finding some kind of return in it.

Do you think about "goodness"?

No. Sometimes I hear from other people that they're concerned about being a good person, and I roll my eyes. I don't know what that means, “good person,” because you either do things that are not harmful to other people and you act with compassion and accountability, or you don't.

Protestant ideals often equate "goodness" with diligence and labor. In contrast, your work seems to challenge these structures by granting autonomy to your creations. How does this perspective shape the narratives you build?

It has always interested me because of how Protestant ideals often equate "goodness" with diligence and labor. In contrast, your work seems to challenge this by granting autonomy to your creations.

For my whole life, I have been characterized by others as cynical and pessimistic. Which is silly, because I would not have continued making art all these years if I were a pessimist. With every project that leaves me in debt, that doesn't get the recognition I hoped for or even expected, or simply is an artistic failure — I have to be basically stupid with optimism that the next time will work out better, that I will get closer to the truth. And every time, I am optimistic.

The painting Deed is based on stills from the Catherine Breillat film Anatomy of Hell. On the surface, this is a morally confused, nihilistic film. You have Rocco Siffredi, the Italian Stallion, playing a gay man who gets entangled with a suicidal straight woman. And the film seems to be proposing, however problematically, that his having this heterosexual psychodynamic encounter brings him to some kind of salvation. In the end, he pushes her off a cliff and it ends in this violent rupture — is it refusal, pure negation?

Nobody is saved, but something unpinnable is exchanged and transformed between these two characters. In order to create anything, you need to believe that you can move mountains with all the wrong tools and the most ambiguous intentions. Diving into the mess and expecting to reemerge with a revelation — it is hubristic, and it is also a beautiful act of faith.