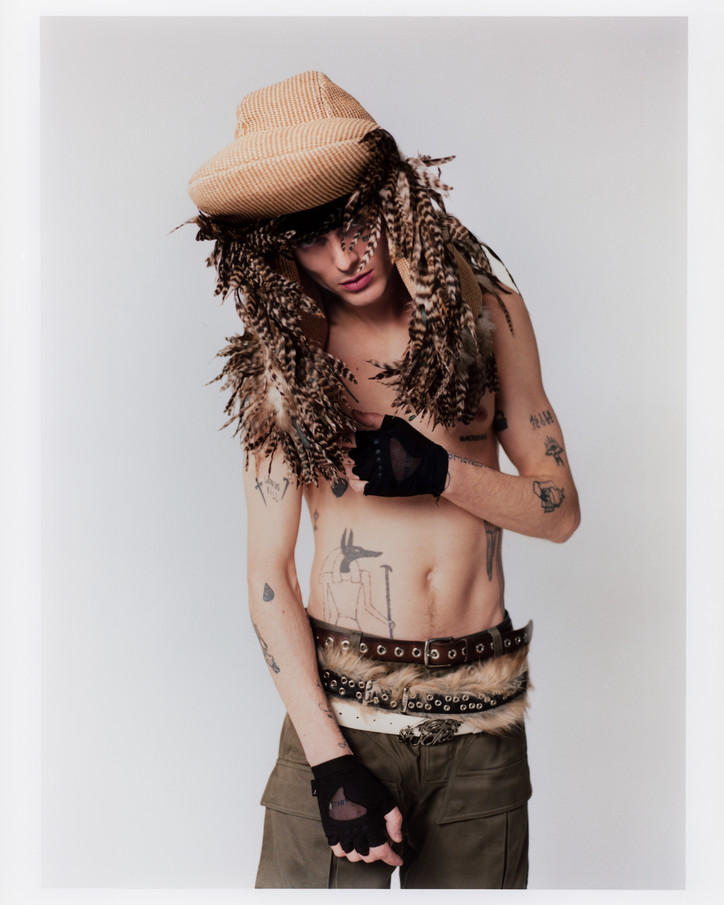

Enter, The Voidz

- Photo by Megan Schaller

I will scream along to gnashing guitar and a crowd that never stops jumping. I will sway with them when “Human Sadness” wracks our bodies into stillness. They will play a then-new track called “Wink,” premiered on Brazilian T.V. days before. They will take requests, and play a guitar-heavy version of “Instant Crush.” I will drop my glasses, and they will crack under someone else’s boots.

Before I return to New York, the band will drop the first part of its name and take up a residency in Bushwick. I will tell Casablancas about the broken glasses under a light rain at 1:30 in the morning. He will give me the pair of pink heart-shaped sunglasses hanging off his shirt.

“Will these help?”

Before the sunglasses and the rain, The Voidz play a memorable set. The third of their four residency shows at Elsewhere, the crowd is pure New York: arms crossed, leather jackets, heads nodding up and down. Casablancas is in the same suspenders and baggy white shirt he wore in Argentina. My publicist friend gets us backstage. I turn the corner, and see guitarist Jeramy “Beardo” Gritter laughing at a joke the tech guy just told him. The outdoor area is replete with familiar faces from Instagram and friends of friends. I’m standing inside, escaping the coming rain. My eyes start wandering the room until I hear the voice.

“I like your shirt.”

I look up, and the man of the hour is looking dead at me. He’s about two feet taller than me. We both have bags under our eyes. I imagine I look just as groggy. To quote Joan Didion, this was “the real thing, the authentic article.” I mumble out a thank you, and relax my shoulders.

He talks to my friend and I for a few minutes before going out to greet fans. He tells us, between laughs and using large hand gestures, about the most interesting gifts he’s ever received. Two stories stick out: the ballerina-style box with a miniature Julian inside, and the woman who comes to every show with a pair of heart-shaped sunglasses. The pink pair around Casablancas’ neck chain jingles as him and the rest of The Voidz walk out into the rain.

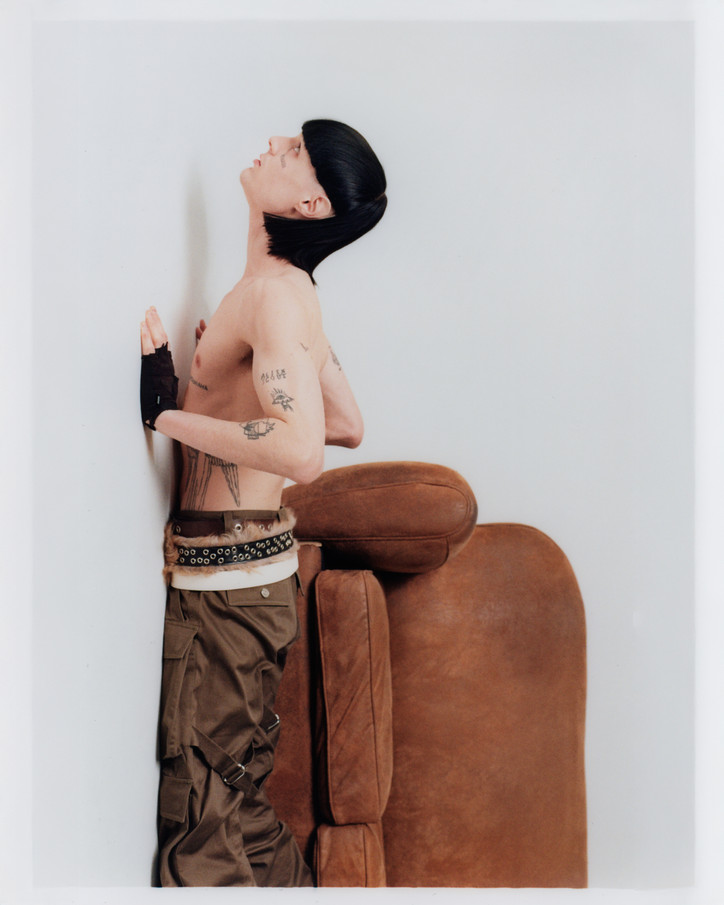

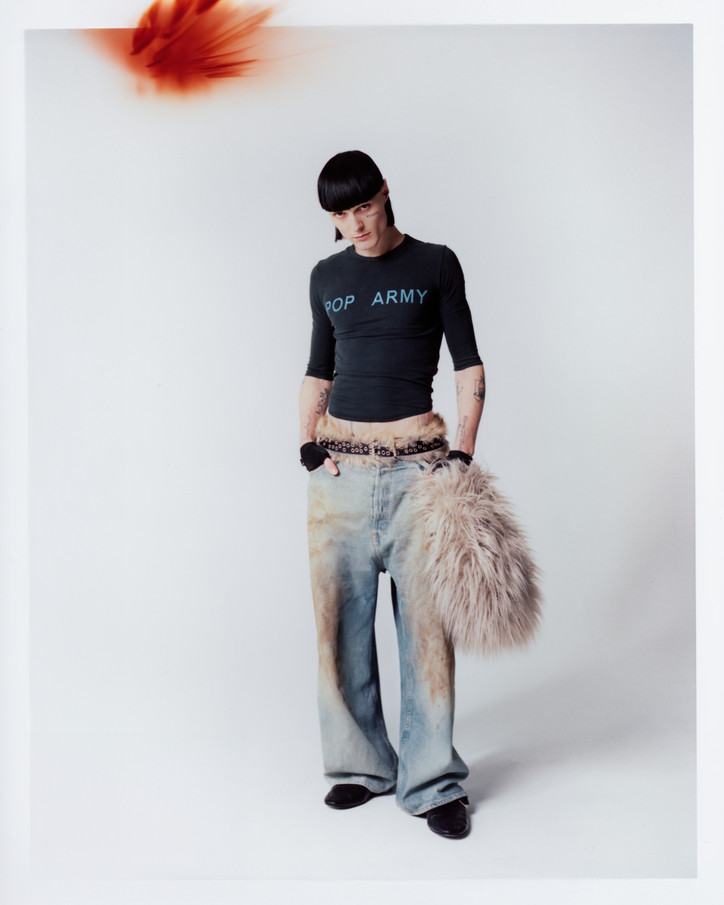

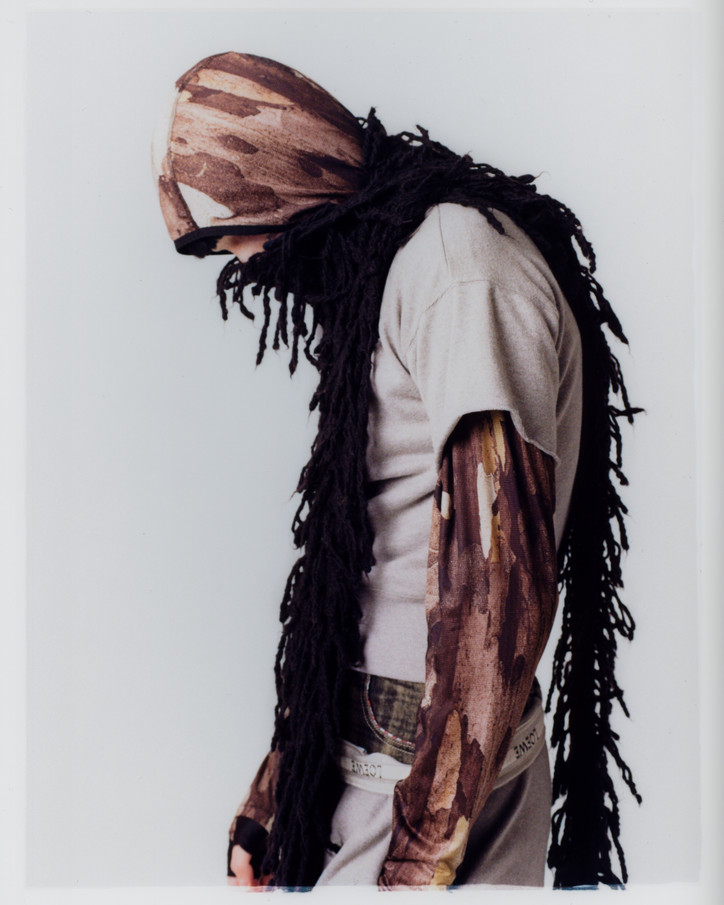

- Photos by Megan Schaller

The night of the final residency, Dmitri, guides me and my makeshift posse backstage. Drummer Alex Carapetis is smoking in the hallway and talking to bassist Jake Bercovici. Beardo, keyboard player Jeff Kite, and guitarist Amir Yaghmai are in the outdoor area.

Dmitri leads us to a door with “THE VOIDZ *PRIVATE*” taped to the front on a loose paper. I take a deep breath, and walk in with two friends trailing behind me. Under pink light, flanked by a tiger and a white cake with “ELSEWHERE ♥ THE VOIDZ” written on top in red icing, Casablancas eats what seems to be a salad. He swallows, and looks up.

“Could you give me a couple minutes?”

A couple minutes. I realize I don’t have a photographer, and my friend Megan pulls a film camera and an Instax out of her Fiorucci bag. The band members mingling backstage are slowly shepherded into the room by Dmitri.

“They’re ready for you.”

I light a cigarette, hope nobody yells at me for lighting a cigarette, pull out a pair of pink heart-shaped sunglasses from my bag, put them on my head, and walk in with Megan.

Summer 2016.

I’m in the passenger seat of a good friend’s red Jeep Wrangler. It is June, and we have both recently returned from separate stints in Europe. I’m home visiting family before returning to New York. I’ve forgotten how humid Florida gets midsummer. A band I don’t know has released an EP called Future Present Past not two days ago, and my friend is eager to blast it with the windows down.

This is the first time I hear the voice. A piercing, muffled howl through a tunnel of guitar and drums as we race down a long highway in Miami. The song title is an off-spelling of the word “oblivious.” The song is dripping freedom, abandon and thought-out scales. The sun and wind hit my face as I lean my right hand out the window, wondering who could write a riff like this, who could possess this vocoded Lou Reed howl of a voice

“What is this?”

“The Strokes!” “No, the singer. What’s the singer’s name?”

“Julian Casablancas. He writes most of their music. His solo stuff is...a lot.”

I throw myself into his discography, from Is This It to Future Present Past, the singles from the Electric Lady sessions, the solo record named after a book by Oscar Wilde, the torrid debut of a band that would be called The Voidz. It was in this way that a band that had already undergone various permutations, been through the eye of several critics, and peaked while the frontman ambivalently stayed, finally got on my radar in 2016 in the passenger seat of a red Jeep Wrangler.

My friend told me Casablancas never wanted to be famous. I read the strange, sparse interviews he would give. In my head, this was one of our last true rock stars: mysterious, troubled, ambitious. Like my friend and so many others years before me, I read of a band and the singer at the helm a few years after their peak through through a screen, an already-late discovery years after an East Village heyday.

- Photos by Sam Singh

“Whatever rules you might have about interviewing, you can forget about them,” Casablancas tells me as I plop down on the couch next to him. I fumble in my pocket for matches and the phone that will serve as recorder. For the first five minutes, the focus will be on one thing.

“So, this cake, is it chocolate?” Bercovici is looking closely at the red icing. “Cherry?”

Yaghmai suggests strawberry or vanilla. Beardo says it’s very light. Casablancas says we have four minutes left. I try and steer the conversation toward music, so we start talking about soccer.

“I guess Beardo and Jeff would play middle, me and Alex forward, and then Jake and Amir back,” says Casablancas. “And then maybe me and Jake can switch.”

“One time we were playing down in Chinatown or some shit, and I look over and see Jake, this full-ass mountain man, hit the fence like uhhh.”

“That was the last time I ever kicked a soccer ball,” Jake says between laughs. “It was a slippery astro-turf, and I was going hard because I'm a fucking team player. I knew I hit the first one, and I knew it looked hilarious. We didn't really know each other that well yet. Right? We were just getting to know each other?”

Casablancas looks up and smiles. “Jake only has one gear: champion mode. I'm always like ‘take it easy,’ and then we were playing and he just fucking slides in.” He pauses. “I'm more of a cherry picker, just positioning everything.”

Most of June for The Voidz was spent between residencies at Elsewhere and Boot & Saddle in Philadelphia. Despite a frontman with an immediately recognizable name, The Voidz are still a new band. A new band needs to get the word out, mess up on stage, and pay their dues in the all-too-familiar trench of a tour bus.

“We had magic moments and then un-magical moments,” Casablancas muses.

“There are a lot of technical things that have to be improved,” adds Beardo. “Chemistry, equipment, trying to make everything sound cooler. And then there's the whole performance of it all, which is just like doing your job as an instrument player or a singer. You're fighting two different sides: the technical equipment and the sound and your crew and then the actual nailing your parts. You can do that, but in this band is not that way. We care about every bit of it, you know? The way that the amp sounds, the way that the whole mic sounds or what mic is sounding...it’s a lot of work.”

“But you try not to show it, and try to make it seem fun,” Casablancas adds. “ It was fun, it just was not second nature because it was all a bunch of new shit. We just want it to feel different each show, with varying levels of success.”

The band was received with mixed reviews at their outset. Then with Casablancas’ name attached, it was dismissed as an indulgent noise rock solo project by some and hailed by others as a clean break from the large shadow cast by The Strokes. Their frenetic debut as a band, Tyranny, admittedly took a while to grow on me. A cacophonous storm of metal and rock and classical and jazz, it’s hard to grasp onto as a record. The Voidz live is an overwhelming assault on the senses, but one entirely grounded by how cohesively they tie these influences together. With the members themselves coming from so many different bands, this catch-all approach to rock—one that takes from African music, 80s Russian new wave, Turkish rap, and random YouTube finds, to name a few—is, above all, refreshing.

“Everything you see here, Julian curates,” Carapetis tells me. “He's the tastemaker for all of us, and brings all the best parts to the surface. The lyrics, the melody, the way we all come up with ideas. The magical moments, they’re not just from the ether. I felt that tonight. You get on stage and remember everything. It's that synergy we have, that confidence in each other.”

Casablancas is quick to chime in. “It's a natural thing that we do. We like versatile things so we talk about it and listen, but they also just play such different stuff! I'm always following them around with recording machines. One day I walked in [to practice], they're just playing ‘Pink Ocean’, and I'm like ‘the fuck is this? This is amazing!”

The Voidz’ sophomore effort Virtue is comparatively more streamlined while still keeping to the devil-may-care attitude toward music the band has fostered. The band continues to experiment with structure—bouncy guitar romp and lead single “Leave It In My Dreams” is immediately followed by “QYURRYUS,” a roiling explosion of horns, vocoder, and instrumental layering. All this said, there’s a noticeable absence of something as experimental as signature song “Human Sadness”, an 11-minute monster with roots in Mozart’s “Requiem Mass in D Minor” that served as the lead single for Tyranny.

“I'd been wanting to do like a ‘November Rain’ long-ass song for so long...it wasn't like that much of an ‘I have an inspiration’ moment.” Casablancas smirks. “It's unsexy, when you boil it all down.”

“It's the first time I've seen someone be so passionate about like, creative information,” Carapetis adds. “Capturing it, always chasing that thing. I've never seen that in anyone, that passion.”

The music everyone is listening to right now is as all over the place as what they’re making: Creedence Clearwater Revival, Nils Frahm, “Mad As Hell” by U.S. Girls. “Sometimes, it's street musicians in other countries on Youtube,” says Casablancas. “Just glorious, sublime stuff.” I ask him if he ever saw street musicians playing tango in the streets of Buenos Aires.

“I didn't see any.”

“That's one thing you have to go back for.”

- Photos by Megan Schaller

When The Voidz play Teatro Vorterix, the stage is solely illuminated by neon lights. There is no spotlight, compared to the brightly-lit sets of openers Promiseland and Rey Pila. Nobody’s face will stand out from the gnashing wall of pure sound coming off the stage.

Months before they arrive in Argentina, an activist named Santiago Maldonado will disappear after police gun him and other protestors down. The day before they arrive in Buenos Aires, his body will be found floating in a river.

“What a bummer about Santiago,” Casablancas says to the crowd. There’s applause, tears, and solemn nods. Then, the howl of a world-famous fight song.

“OLÉ, OLÉ OLÉ OLÉ! HERE COME THE VOIDZ! OLÉ, OLÉ OLÉ OLÉ! JULIAN! JULIAN!”

Onstage at the last residency in Brooklyn, Casablancas’ sarcastic drawl is present as ever. “A lot of people from Bushwick here tonight.” The crowd applauds, and Casablancas gets quiet, shuffles for a bit, and jokes to the crowd before the band plays “Pyramid of Bones.” “You can cut off my mic from anything tonight. I’m not special.”

Both Virtue and Tyranny play with ideas of political anarchy, albeit one that feels detached. In a world where black and brown bodies are policed and rap has become the genre at the helm of calling out political wrongs, what place could punk rock still have? At least they’re keenly aware of the fact: on “Pyramid of Bones” Casablancas’ distorted yowl warns the listener not to “ever listen to the white man’s lies.”

“I think [Virtue] is trying to be a more positive thing,” Casablancas mentions. “That's the thing is that people were just not aware of things. Tyranny was like "wake up people!" The fact is that only liars and cheaters and bribers get to rule. Once that happened, now everyone's freaking out. Virtue is like ‘now we must solve things, now that you are awake!’ I guess that’s the tone difference you hear, but it's not like there's specific instructions. Music is escapism.”

“The last album was a piece of fire,” says Beardo. "This album was a candelabra on a mountain...a scorched mountain.”

For fans and critics alike, for the fervent ones who were there from the start, The Voidz mark an alpha and an omega. For some Strokes purists, there is a begrudging acceptance that Virtue, as a record, is good and The Voidz are more than a self-indulgent solo project. For others, it’s another kind of marker: the end of “the last rock stars” Lizzy Goodman immortalized in her best-selling book Meet Me in the Bathroom, the exciting start of something new. The pink ocean of tears cried by those anticipating a reunion of the old guard is drowned out in a new generation’s mosh pits. What Goodman froze in oral history was just another rock movement, but music is more than just history: it’s the new discoveries. It’s the tinkering and touring and creation of new words.

This weekend, The Voidz will race down Pacific Coast Highway to play Beach Goth, a festival hosted for years in California by indie rock up-and-comers and Cult Records labelmates The Growlers.

I’m told by friends from the West Coast that Los Angeles, where most of Virtue was recorded, has no seasons and the California sunshine makes for dry and pleasant heat. In this same desert landscape, a band called The Doors found both vice and virtue. What could stop another band from doing the same?