Giant Women: Exploring Art, Autonomy, and Introspection

The show’s namesake piece, Anita Steckel’s Giant Women on New York (Coney Island), 1973, is part of her greater Giant Women series. A nude woman, stylistically larger than other figures, lounges outstretched in the water of Coney Island beach. Known for mixing erotic imagery with recognizable landscapes, Steckel protested art history’s double standards by portraying female nudity on her own terms. Her figures take up space both literally and figuratively in her landscapes, emphasising an ongoing uphill battle for women to secure their place in the cannon.

In 1972, a Republican legislator demanded that Steckel’s solo exhibition, The Feminist Art of Sexual Politics, be cancelled, considering her works too obscene for the public. Steckel responded to this accusation by forming the Fight Censorship Group, which would go on to advocate for the right for women to use male nudity and sexual subject matter in their art works, just as men did. While we might like to think this kind of censorship is some far off dystopian reality, it’s all too familiar to the political control we’re facing again today.

Bringing female experiences to the foreground of painting was part of a larger initiative to give humility and dignity back to the sitters, especially when painted in the nude. Male artists often depicted their models as mere sexual objects or muses, painting them as nothing more than nude flesh, disengaged from personhood. Alice Neel was uninterested in producing the next Grande Odalisque, and opted to humanize her subjects through her honest and raw depiction of the nude figure. In Ruth Nude, Neel’s unforgiving re-examination of the female body takes away an overly idealized exterior. In doing so, Neel provides an opportunity for the viewer to inquire about the sitter’s inner psyche.

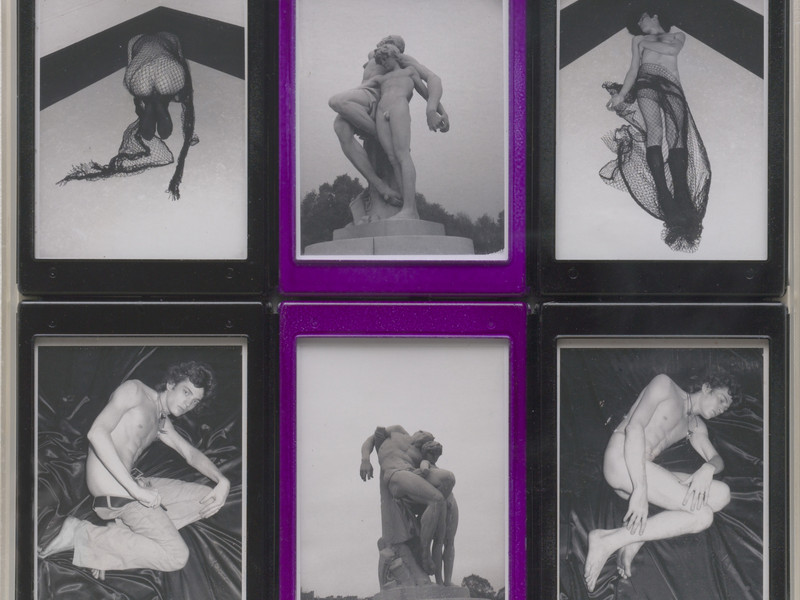

This unvarnished approach to the body can also be seen in the work of Joan Semmel, who began as an abstract expressionist and later turned to figurative painting. Her sexually charged imagery was part of a larger second wave feminism initiative for women to explore and get in touch with their bodies as a means of taking back ownership.

Semmel did this by painting her intimate angles of her own aging body, depicting its inevitable changes. In other pieces, she intentionally leaves the face of her figures out of the frame, allowing the viewer to impose themselves into the work. She depicts visible sexual pleasure from a woman’s perspective, outwardly rejecting the male gaze. Bottoms Up (1973/1992), is part of a larger Overlays (1992—96) series, combining an underpainting from her Erotic Series (1972), with later imagery from her Locker-Room paintings (1988—91). Semmel revisits the same themes throughout her life, emphasising the lifelong commitment she has made to her figures.

These women not only refused to sacrifice the woman for the artist, but created a community to support a greater discourse surrounding what stories we highlight in art history. Giant Women On New York seamlessly demonstrates this unending determination to compound the worlds of activism and art, while also revealing how much work there is left to do.

The art landscape is changing quicker than we can keep up with, and with that, our commitment to the figure seems like a distant memory. Giant Women On New York feels like a call to the past, a point of reflection in a time of turmoil. There is work to be done and work to protect regarding women's rights. The works of these “giant women” provide us with opportunity to ruminate on the complexity of the female experience, and encourage introspection.