I Could Cry Power: Lutas

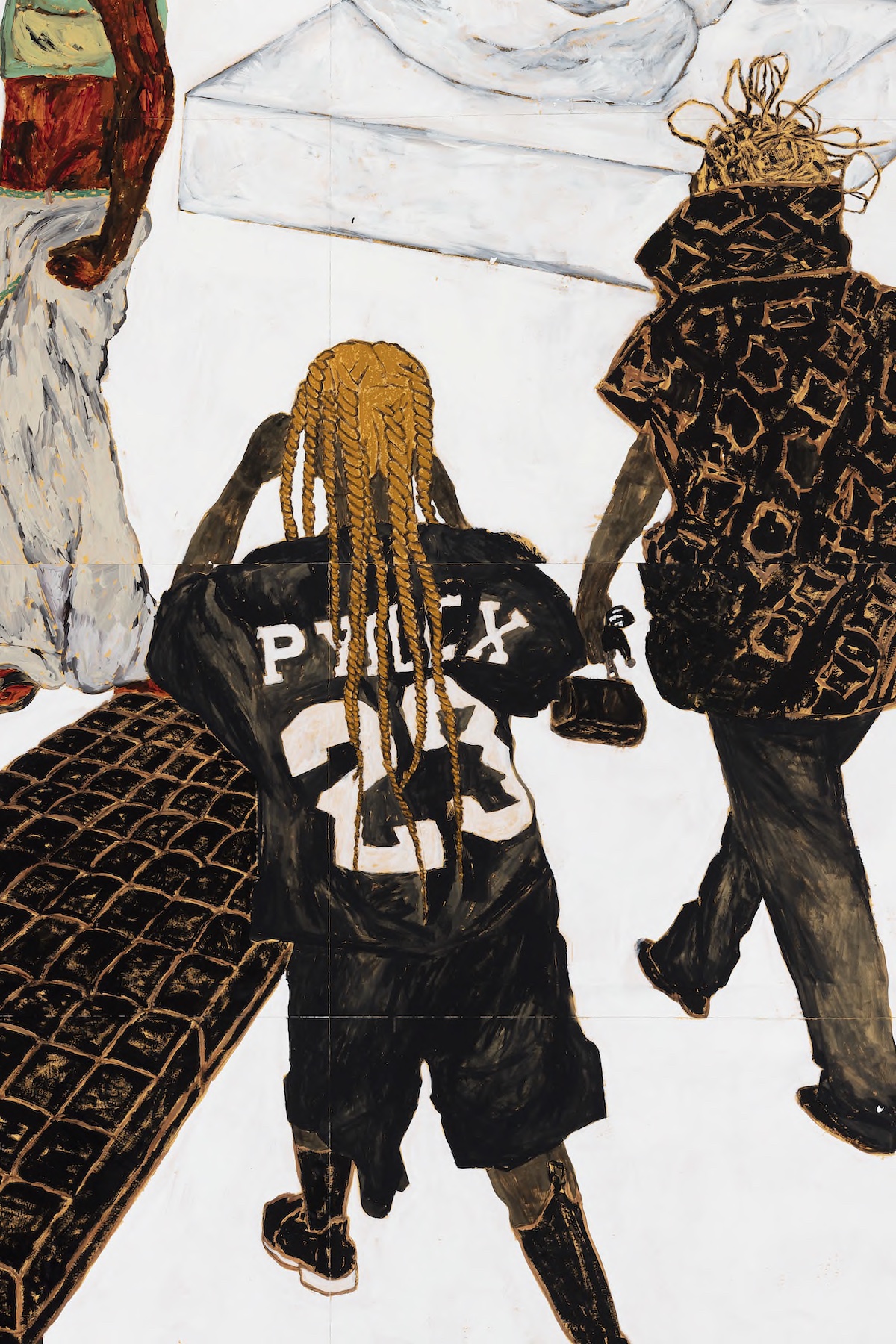

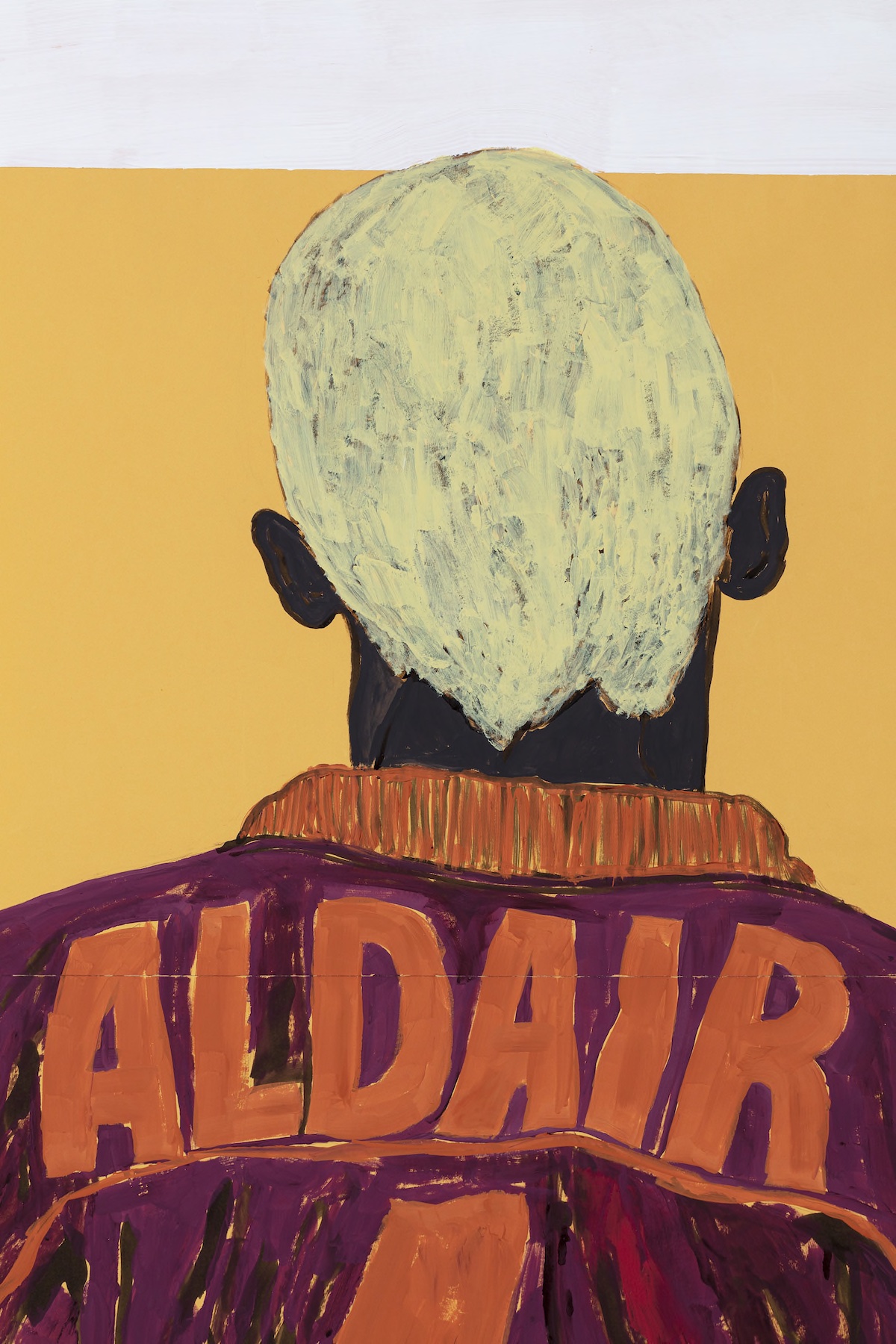

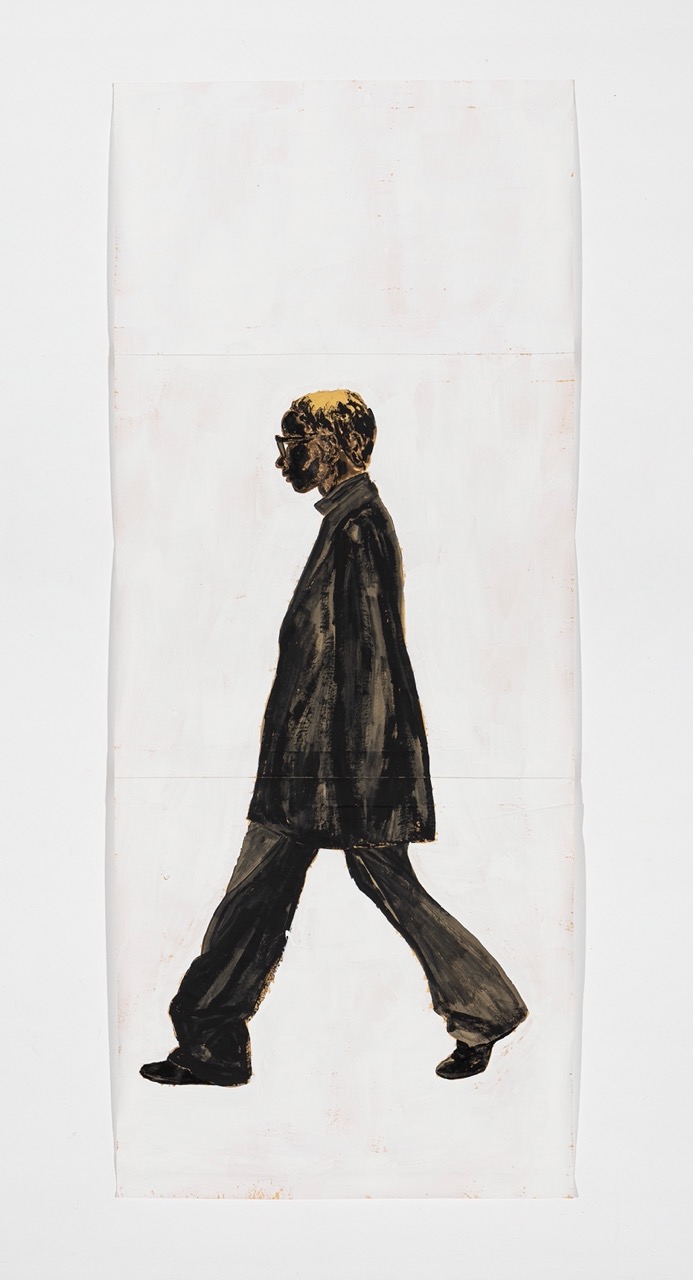

However, Alexandre quickly realized that a victory solely based on material advances was, ultimately, only symbolic. Grounded in this realization, he began working on his series A Novo Poder [A New Power]. In this series, Alexandre began to critique institutions of power, specifically in the art world and the exclusion or inaccessibility of these spaces of the people and communities in which he grew up. In doing this, the artist was attempting to utilize the clout and success he had gained to usher in a new era of inclusion – in Brazil and globally. He began to draw people who looked like him, or could be from his community in the Rocinha, into scenes depicting museums, galleries and art institutions. The concept is further demonstrated by his performance art piece, Rolezinho, which is a conceptual extension of his Nova Poder series. Through Rolezinho, the artist invites and facilitates individuals of African descent from various communities around Brazil to come to his exhibitions in other countries. At the center of Alexandre’s practice is a mission to create visibility for his community in the Rocinha and communities like it around Brazil, showcasing the beauty that persists in his culture, even atop the systems and institutions which have historically thwarted its proliferation.

EMANN ODUFU— Though there is a throughline of oppression against people with darker skin around the world, Race is perceived very differently outside of the US context. To put it simply, the US has its own history and internalization of the trauma of slavery, oppression, etc., that is similar but different from Brazil, South Africa or Guyana, where I'm descended from.

But yet, certain things remain. For example, when I first went to your show at the Shed, I remember seeing a connection between the "papel pardo" and the "brown paper bag test" that has significance in African-American culture. Basically, in the US, if you were darker than a brown paper bag, then you were a dark-skinned Black, and if you were lighter, then you were light-skinned. Various social privileges or disadvantages were associated with where you fell on that color spectrum.

In showing your work in the context of the US, a place with similar, yet different, conceptions of racial identity than Brazil, do you feel that some of the nuances of your paintings and message were lost in translation? Did the works take on new meaning in the context of the US?

MAXWELL ALEXANDRE— You will always lose something when the work moves from one context to another. This testimony you told about the brown paper bag is something I hadn’t known about, but I found it very interesting and intriguing.

In the case of the Pardo é Papel series, Brazilian viewers can most readily understand the content, in various layers that are more accessible to them, because I don’t need to explain about the term pardo. In Brazil, the audience is aware of pardo as being a term for brown kraft paper, since it is often used in basic school activities with children, while they are also familiar with the use of pardo to denote a tonality of skin/race. Your example of the bag is still about being black, white or dark. In Brazil, pardo emerges as an alternative for a person to stop being black, the famous process of “redemption.” Pardo as a way of concealing negritude, washing the identity, “whitening” the population, making it closer to white. This is one of the most important discussions that my series raises. But I also believe that every truth conceals another, and no truth is ever complete. So, in this case, I accept the loss of fundamental layers that made me conceive the work the way I did, so that I can be surprised even by a contradiction, either by a change in the concept of pardo in the course of time or in another cultural context. Art is nearly always about staging, and contradiction in this arena is welcome.

You created the Glorious Victory, which showcased the upward mobility of black people in Brazil and the acquisition of material objects that characterized that mobility at a time when you were also beginning to rise as a visual artist. In this, your exhibition became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Novo Poder also chronicles a new stage that you are still in the midst of, where you are now harnessing the power created in your “glorious victory” into things that can make a social impact in your community and around the world. Do you look at your process of creating artwork as a form of alchemy, and if so, how are you creating the world or your world anew through your work?

MA— My activity basically consists of making notes and joining things together. I am evidently creating a mythology of my own based on these two practices. This is intentional, but it is also for reasons of necessity that I wanted to be here. What I mean to say, is that being an artist is a way that I have found to maintain nostalgia, while simultaneously living in a state of uneasiness. In this system – making and thinking – which involves a feedback loop, it is all about my own biography, both lived and invented, because I think that I am the measure of all things. Ultimately, everything I make is a self-portrait.

There is something very spiritual about your work. I read that you consider your work to be prayers, your studio a temple and that you had an Evangelical Christian upbringing. I know that you have since broken away from organized religion, but one of my favorite works by you was shown at David Zwirner and is entitled, Me dê a maçã or Give me the Apple. In it, we see a scene that channels the Garden of Eden, with serpents on trees and Hieronymus Bosch's Garden of Earthly Delights. There is a strong symbolism of the apple phone, with its logo channeling the forbidden fruit that brings forth the fall of humanity. It's a vibrant painting, and a lot is going on. Please give some context to this work, expanding on some of its symbols. What were you trying to say with this work?

MA— The work Me dê a Maçã [Give Me the Apple] takes its title from a verse in the song "Deus das Ruas (God of the streets)” by rapper BK’. To translate the verse into a painting and evoke the atmosphere I created, I am going to bring the complete excerpt from the track: “De poder eu tenho fome/ Eva me deu a maçã, era só o número do iPhone.” “I am hungry for power [Eve gave me the apple, it was only the iPhone number].”

Although BK’ is a close friend of mine, I didn’t consult him about the idea involved in this specific verse. But the words "Eve" and "apple" were enough for me to interpret a Garden of Eden within my own mythology: black characters, the mascot of the famous yogurt brand Danone playing the role of the serpent in the Garden; the Capri pool patterns illustrating the clouds in the sky and the lake; and the forbidden fruit, the apple, a metaphor for the iPhone, the Apple brand, whose logo is an apple with a bite taken out of it.

Apple is one of the most sophisticated brands in terms of design and technology, one of the largest corporations in the world today, and its logo, the apple with a bite taken out of it, is consistent with the desire the brand creates in its consumers. The iPhone is one of the brand’s most famous and highly-demanded products, and despite that it is very expensive, it still appears constantly in the lives of people from the lower income levels. The sacrifice to obtain the forbidden fruit exists, and this cell phone has become established as a current trend in consumer culture. It's a big phenomenon. In the Eden I created, iPhones grow on trees in the Garden, and the characters, all of whom are black, deal calmly with happiness and the pleasure of having these costly and symbolic objects available to them. They fill their baskets with the cell phones that are scattered around on the grass, they accept the serpent's invitation for them to be consumers. There is no shortage, and they have no fear of sinning or being judged for excessively consuming a product that is itself a symbol of capitalism, luxury, desire, and ostentation. Ostentation is part of the game of vanity, power, and self-esteem.

The way society judges futility, pride, and vanity is different depending on whether a person is black or white. It's natural for a black person to feel guilty when they start making money and enjoying their wealth. It is not acceptable, especially in Brazil, for black people to deal calmly with their beauty, vanity, pleasure, and luxury. Our consumption and acquisitions are soon criticized, and they quickly seek to load us up with social responsibility, saying something like, “What do you mean, you’ve gotten ahead and now you are buying a watch? You need to lift your community out of poverty. You can't keep showing off.” You are supposed to constantly concern yourself with activism, be political and socially responsible all the time. The right to sin is reserved only for white people.

In my Eden, I speculate on the possibility of black people being able to sin, to take a bite out of the forbidden fruit without shame. This is the scene I painted in Me dê a maçã [Give Me the Apple].

It is highly apparent that you make an effort to remain grounded in, legible, and accessible to your communities at home in Rocinha and across Brazil. In addition, you are very intentional in finding ways to activate your work with physical demonstrations such as "Rolezinho" or "Descoloração global." I love how these elements of performance art/art activism exist as a conceptual extension of your paintings, the Rolezinho mirroring your New Power paintings that place black bodies into elite art institutions, and your Descoloração performance piece complimenting the figures in your artworks which have bleached blonde hair and pay homage to the popularity of that hairstyle in Rocinha culture. Please tell me about your process of adding these physical demonstrations into your practice, and how these demonstrations are an outgrowth of what I perceive to be an interest of yours in art activism.

MA— I am not an activist, but an artist.

Activism is what’s expected from a black person, it’s a stereotypical label that applies in the case of a strong black person, who thinks, makes demands, questions, competes, is strategic, and knows how to position him or herself. I think that all these attributes are also part of the makeup of a good artist, so it is important that I have them. Being an artist is a luxury, it is superfluous, and from a social point of view, when successful, it is a divinity; it is the light, the profession that confers a status of the highest prestige. That's why it's so hard for me to remain only in this place of an artist, which is not customary. The word “activist” helps to better define and encompass my place as a black person, so it is necessary to complement my status as an artist as a means of putting my mind at ease, an aid for me to come to grips with my exclusive position. All of this sounds to me like people saying: "Why is that black guy just idle, doing these meaningless things? That's a thing for white people, that black guy should be struggling to lift his people out of the misery that we have set up for them forever." In other words, being black is to be miserable when one is down, and then, once one rises up, one has to continue the struggle, maintain the "activism." There are only these two places for people like me, misery or struggle, never just idleness, plenty of leisure for the thoughtful spirit.

I must reject this label of artistic activism because I want to fully enjoy all the benefits of being an artist in society. Being an artist is synonymous with freedom, craziness, senselessness, and just idleness. These are the attributes I want for myself. I don't want commitment. I want the idleness. I want to not have to do anything. I want the lack of any practical purpose, which is the most valuable thing that art has to offer, especially in a world where we must have a “why” to everything, where everything has to work; I want to have no usefulness. I don't want to be an example, I don't want to fight for everything, including for my own survival. I want to be able to contradict myself, I want to be negligent and still be forgiven like white people are.

Don’t demand activism from me, I am an artist. Art is unknown, questioning, with no commitment to objectivity, it is not exact. And yet it is a behavior, a posture and the artist’s place is on the fence, maintaining a state of permanent questioning.

What I'm saying here is related to the previous answer about the Garden of Eden that I painted in the work Me dê a maçã [Give Me the Apple]. I want to eat the forbidden fruit. Let me sin. Sin is the food of life.

As an artist, you are not one to shy away from institutional critique. You are acutely aware of the history of exclusion and the hypocritical nature of art institutions that use the work of Black artists as a band-aid to histories of oppression and discrimination, in some cases enacted by said institutions. Recently you had a dispute with the Inhotim Institute where you asked for one of your works to be removed from a group show of 33 artists that was created to be shown in alignment with the “Dia da Consciência Negra," declared a National Holiday in Brazil in 2017. Why is it vital that you use your platform to speak truth to power, and how do moments like these help to create pathways to a more inclusive and equitable art world? How do you walk the line between honoring your belief system, and navigating an art world where power is skewed toward the institutions, and speaking up too much can get you labeled as an angry "black who attacks"?

MA— We could say that this stance of mine is only possible as my work’s growing in potential and I become each day more relevant in the scene. But since the beginning, I have been laying claim to my career steps and negotiating them with autonomy, and I've already had several confrontations with art agents and institutions because of it. Of course, at the beginning no one listens to you, and it makes sense that they wouldn't, when you haven't proven yourself yet. In other words, in the games of power, vanity and money that sustain the art circuit, you only gain a voice once you have generated credit in that system. And that's what I have been doing – just look at the amount of credit I have garnered for my name and work in recent years. Why are they still unable to accept my size and relevance? There are no precedents for my case. If you analyze my accomplishments and résumé, you won't find parallels, even among white artists, in terms of my performance in the professional art circuit, in such a short span of time. And my work’s excellency, my ethics, and my stance as a professional artist are the basis for making my objections.

How does the political climate in Brazil, with the tensions between the liberal and conservative factions of government and things like the recent insurrection, threaten this "New Power" that you are channeling in your work? Does the work take on new importance within this political climate?

MA— The idea of Novo Poder [New Power], which is access to contemporary art, is something new for the black populations in Brazil. So, I believe there is a vulnerability posed by the current political context, as all censorship aimed at art institutions will reverberate as a lack of funding, closure of spaces, etc. On the other hand, I feel that moments like these, despite the weakening of institutional support, provoke cultural agents and artists to engage in a series of actions for liberation, seeking even more insistently to reimagine more equitable structures. And I think this rebellion has much to do with my work, since even though I know how to be a player in the game of the art market, I still work sincerely to incite the implosion of this hegemony at all times.

I don't know if the work takes on a new importance, but we know that crisis moments tend to strengthen work in the arts. I think, for example, about how Brazil is an ideal scenario for art, seeing that chaos is an essential factor for creation. If Bolsonaro were reelected, this would be a very important moment for the spread of other artistic ideologies, which would be very important for the resistance of this scene.

I know that music, especially genres such as hip-hop and rap, play a huge role in the creation of your work. The title of your exhibition at David Zwirner in London was taken from a Tyler the Creator lyric. You also created a playlist with many hip-hop songs for the exhibition. At your exhibition at the Shed, you had a painting that featured a character reminiscent of Tyler the Creator clad in his clothing brand, Golf Wang. Aside from this, a lot of your work channels lyrics from popular Brazilian rappers. You once said your work is inspired by "black poets who have had the same experience as me." I relate to that, because hip-hop has had a similar effect on my life. I'm interested in what you're listening to at the moment, and it doesn't have to be hip-hop or rap; it could be anything. What's on your playlist now?

MA— Yes, music is a pillar for the construction of my work in painting. Specifically rap. I am a fan of Tyler, but I still haven’t painted him directly, although some of my characters are dressed in his clothing brand. Tyler has inspired the aesthetics of the Pardo é Papel series since its genesis.

My playlist includes: Rosalía, Playboi Carti, Kanye West, Filipe Ret, cosme sao Lucas, Gilberto Gil and Solange. But Caetano Veloso is the one I have listened to the most.