"I Swear to Become my Body": Greer Lankton

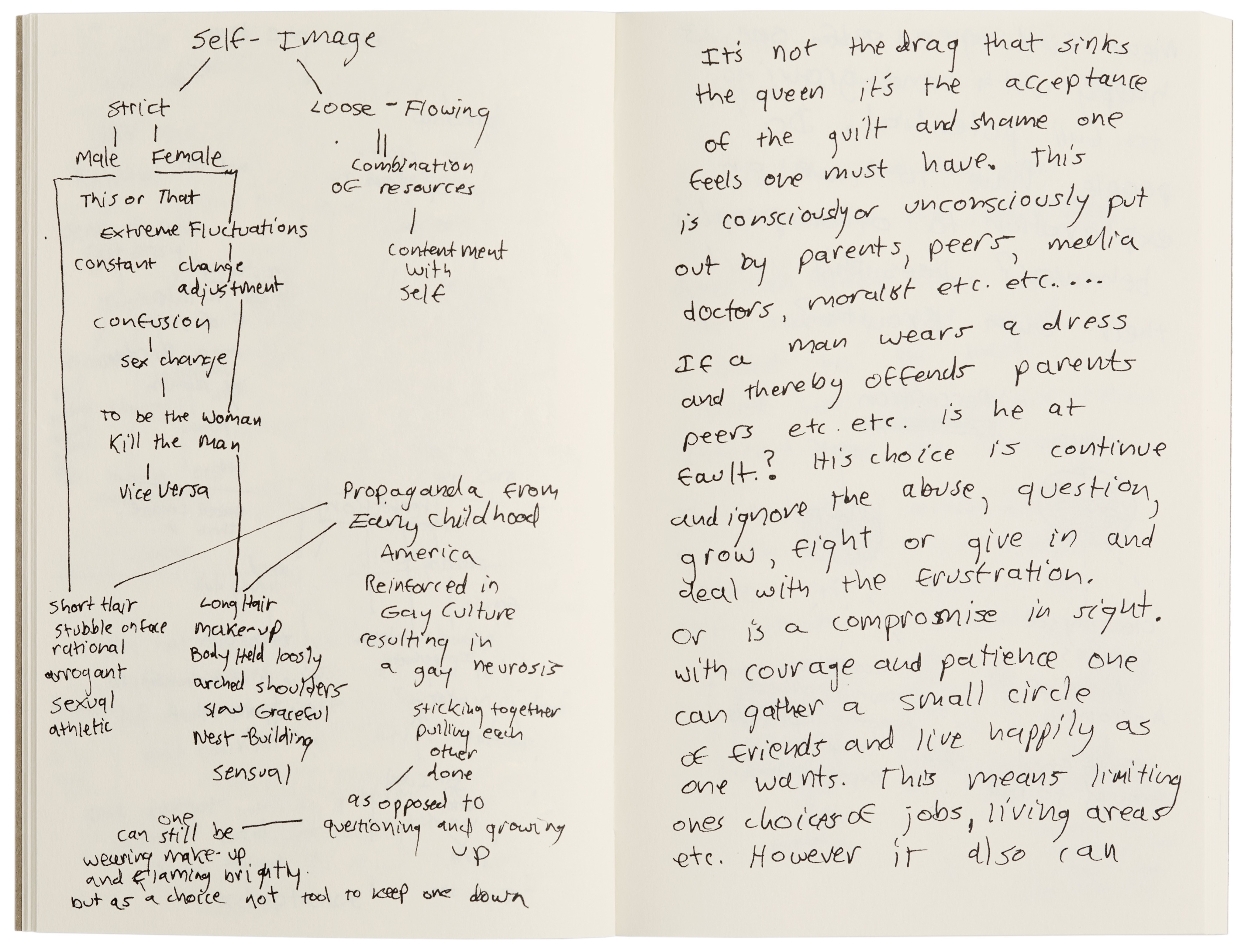

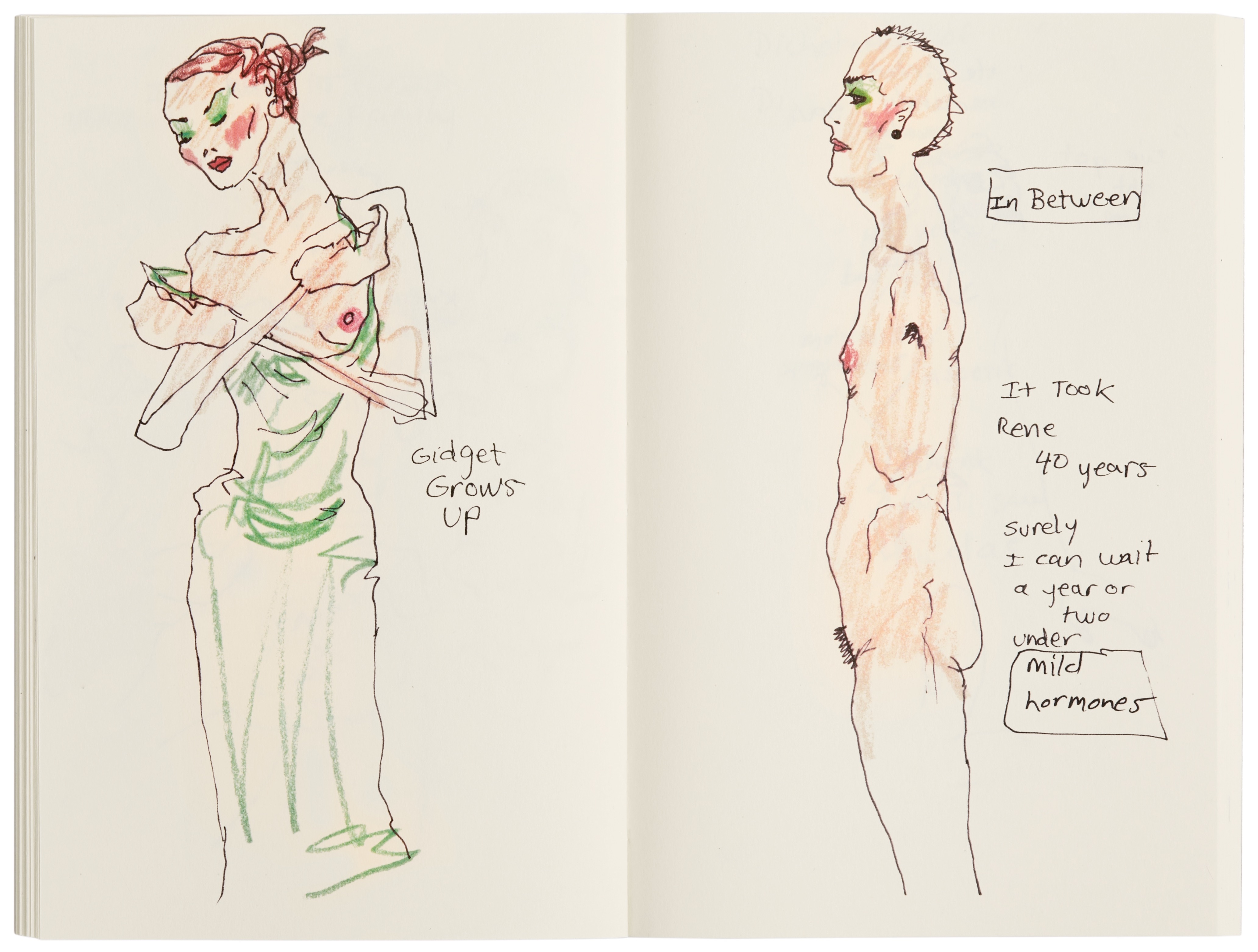

“If you think you have the wrong body, you are always going to think about it,” nineteen year old Greer Lankton pens in her Sketchbook, September 1977. A running theme throughout, we see it questioned and translated through an arrangement of sketches, diagrams, and scattered but mindful musings of a young girl attempting to reconcile with herself. She dives headfirst into deep contemplation of gender, her surroundings, and her inner world. The pages span over two years, beginning just prior to her move to the capital city and leading up to her sex change. In the early stages, she frantically contemplates her body’s inner workings, chronicling her consumption and her battle with asthma in a diary-like fashion. As the journal progresses, it transforms into a collection of etched portraits and depictions of skeletal figures, exploring the possibilities of a social and medical transition.

I initially read Sketchbook, September 1977 in an afternoon or so, unable to look away. Lankton was around the same age as I was when I became distinctly aware of the dissonance between my mind and body, which ultimately led to not only a gendered transition, but an entire shift in my world view once I moved to New York. I felt a tender sense of empathy as she approached the threshold from teenhood to womanhood, a time of whimsy and transformative curiosity. Her youthful longing for clarity resonated with me. Living in a vessel, or “vehicle” as she calls it, lacking a manual is a universal human experience. Yet, reconciling your body and mind as a transexual can be isolating. There were moments when reading her inner dialogue from an era before I was born, rife with heartfelt questions and commentary straight from the privacy of her pen, that left me breathless. How could someone who lived decades ago feel so close? How did she tap into my thoughts?

Many of Lankton's questions can be seen as an expression of her desire for self-preservation, often followed by affirmative sentiments as if she is reassuring herself that it's alright to continue, to survive. She pleads with herself to believe, 'It couldn't be worse than it was... It's worth it.' While contemplating the polarizing commentary and criticism surrounding her life and work, I found this early journal to be a testament to the author's character from a young age. Her pursuit of growth in the name of survival tells the story of a tragically hopeful girl.

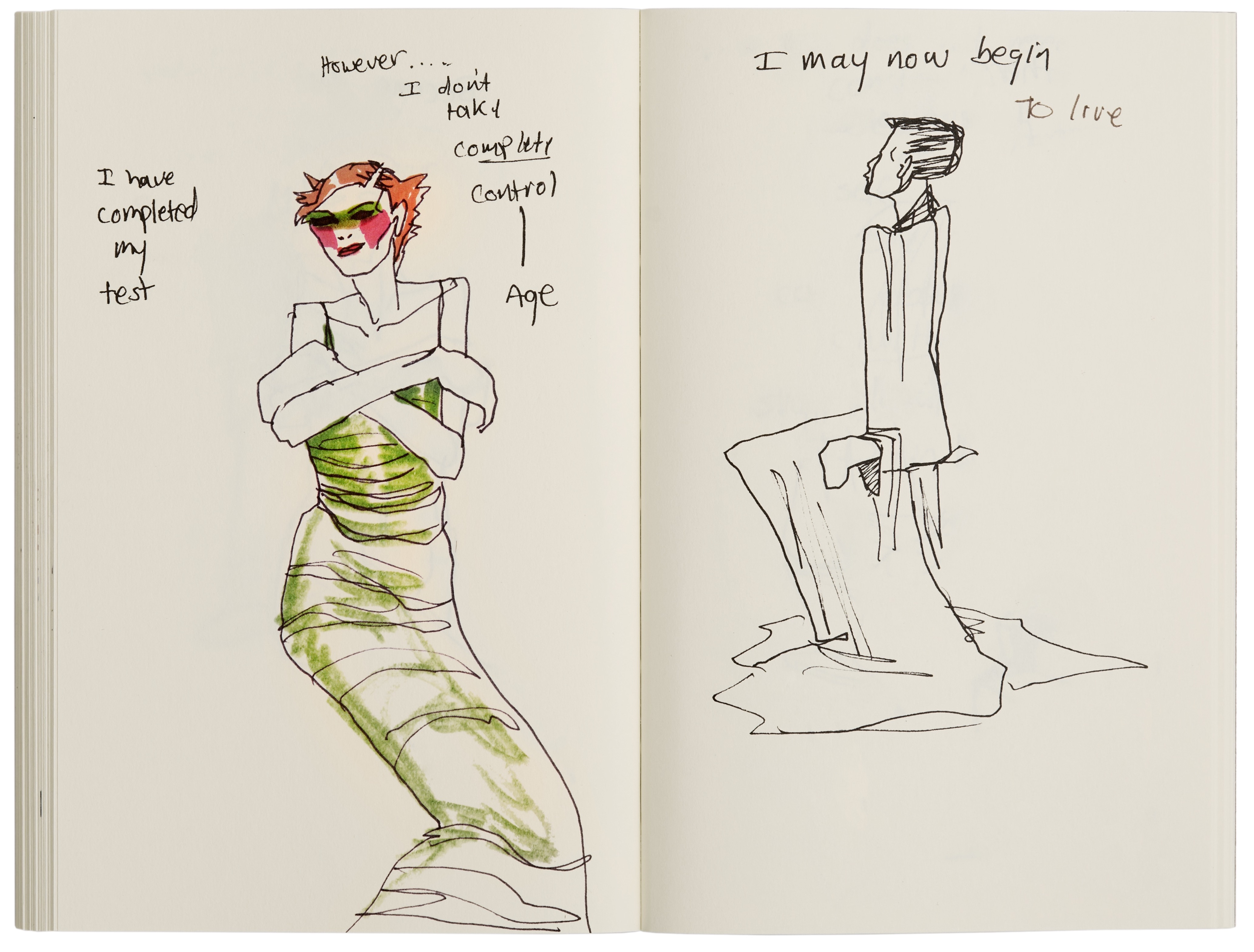

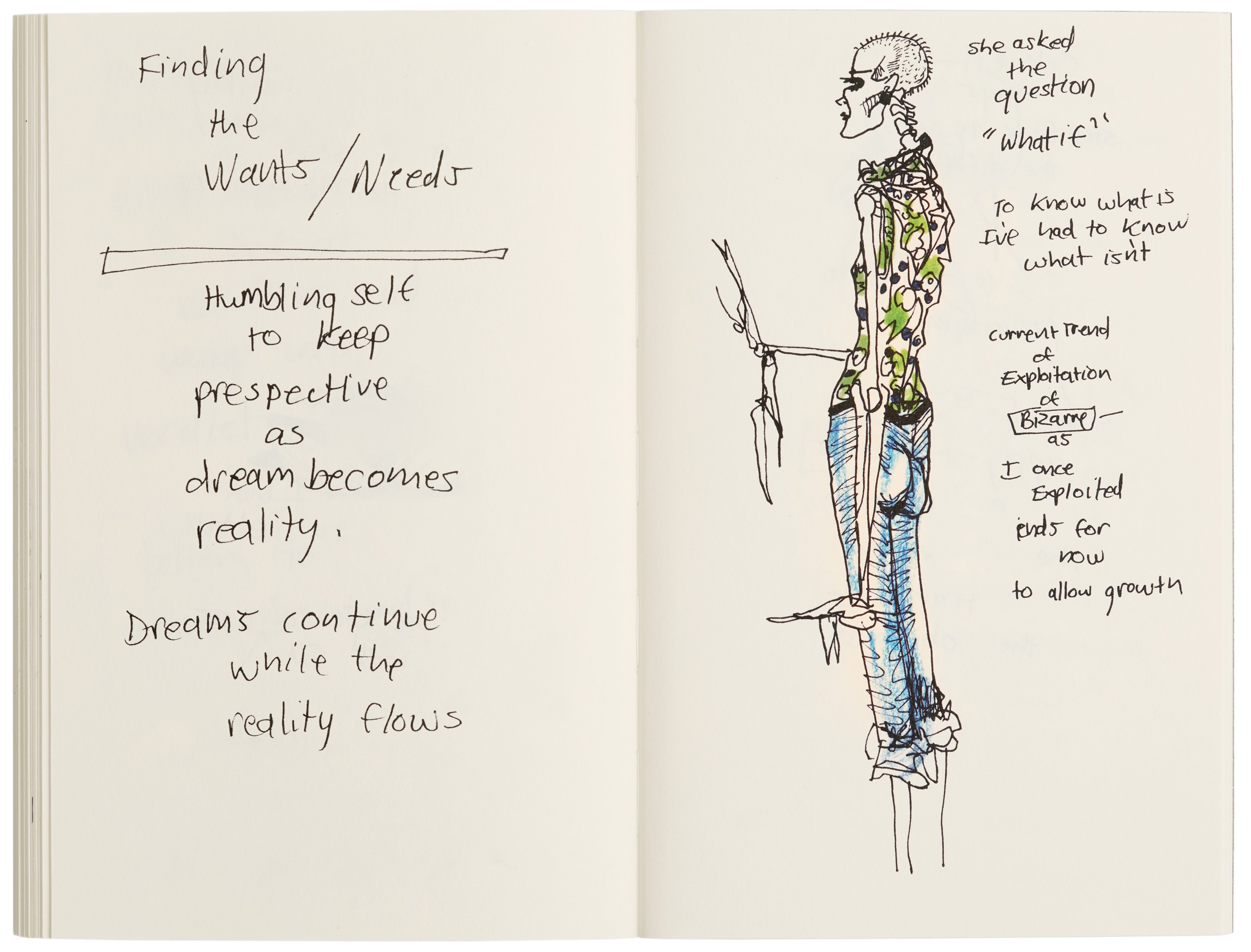

Dealing with the unknowns of transitioning, the artist engages in pointed conversation with herself about the proposed material reality intertwined with her gender. Romance, public perception, her relationships and her duties to her body at the cost of becoming… were suddenly tentative to change. Fear of failure and rejection would naturally set in for anyone, and it does. In defiance, she reminds herself gently, “The truth is, I’m alright… there’s nothing to prove.” The latter half of the journal is mostly sketches, exhibiting a medically informed knowledge of the bodily form, nodding to her obsession with the skeleton as we see in the stories she would come to tell in her renowned craft. Lankton seems to showcase depictions of herself in and around many of the drawings, expressive in her continued grappling with what it will take to answer the question of her transsexuality. Nearing the final pages, she states that she will be “free to continue,” and that she has.

This sketchbook provides a prologue to the Greer Lankton the world would come to know. Her legacy has long outlived her in many of her sketches that would later become life-size dolls, inspiring installations filling entire rooms. As I read September 1977, I felt guided by her voice narrating a journey from the metaphysical world into her body, overlooking what would become her actualized form and eventually her life’s work. The detailed insight to the artist’s mind gives way to a sociological and painfully human approach to understanding oneself. “Now that I have a glimpse of self I have caught the glimmer outside of my own body,” she wrote. As her life and career blossomed into a staple presence in the art world of the 80s, we would see many of the fruits of her emotional labor she documented fervently in 1977. This was Greer as she was before her stories were told by others, a girl with the will to transform. I heard her piercing voice as she immortalized herself on the pages, speculation and hearsay falling aside. This was her story.

I’ve said often that transness is a testament to intuition. Led by a profound understanding that our bodies are malleable in nature, we claim agency by assuming the task of evolution. When hearing of Greer Lankton and her work, I was intrigued by the archival documentation of seemingly autobiographical experiences through the crafting of hand-sewn dolls. I saw much of myself in many of them, now with a greater insight into the inspirations of their creator herself. There was an acceptance of her own evolution of body and mind, even if never finished nor always at the same pace. “I will not die, I will become.”

Following the loss of nearly a generation of queer and trans elders in the 80s and 90s, holding her diary feels like an anchor to her humanity, no matter the distance between us. I grew up feeling like the only girl in the world, isolated by my emotions, a belief that was shattered when I met The Dolls. My trans mother once said to me, “You’re not going through anything no one hasn’t gone through before” and it has been a great comfort to me since. Reading Sketchbook, September 1977 reminded me of the same when Lankton wrote above an outline of what seems to be a version of her own face, “I may now begin to live as others have before.”