JW Anderson F/W '19

Of course, the only thing we were left knowing for certain was that we need to get our hands on this new collection.

Peep some of our favorite looks, below.

Photos courtesy of the brand.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Of course, the only thing we were left knowing for certain was that we need to get our hands on this new collection.

Peep some of our favorite looks, below.

Photos courtesy of the brand.

Until now, Lange’s collection has never been shot on models. Styled by Head of State brand director Ruja and shot by photographer Benji Geisler, the lookbook and accompanying video presents some of Lange’s favorite garments in an office exclusive. We had the chance to sit down with Abe Lange to discuss the origins of his collection, making clients apply for appointments, and why he doesn’t post everything in his showroom.

When did you first take an interest in sourcing vintage clothes and items?

Abe Lange— I guess it started partially out of necessity. In North Carolina where I grew up, there isn't a lot of interesting or unique clothing. A lot of people are wearing the same things from Old Navy or Walmart or Target.

For that reason, I wanted something that stood out, but also sizing wise, it was hard for me. I was short and skinny, and they pretty much had either options of stuff that was tall and skinny or short and wide. I took an interest in clothing after looking online and seeing that certain brands with sizing that would fit me actually existed, but they were usually quite expensive and based in Europe or Japan. So I looked into why they were more expensive, and then along with that, I began looking at thrift stores and flea markets like a natural collector/nerd.

I began in late middle school in North Carolina. Honestly, I just learned more as I found stuff and it snowballed from there.

When did you start selling things to other people?

I started selling stuff during college. I went to Sarah Lawrence in Westchester County, much to my dad’s dismay because it was drastically more expensive than UNC, where he was a professor. I kind of financed various things through selling clothes. I didn't really have a voice or anything that I was putting forward in terms of expression, it was more just about the clothes that I thought I could sell to make some money. It began as a side hustle.

And then how did you start to see it evolve beyond that?

I don't really have a defining moment as to when it kind of switched from being a side hustle to a real passion or a more serious way to make money and have a voice or express myself.

Honestly, as I started getting more things, and digging in more places further away from home, I would find stuff that wouldn't fit me and that I wouldn't really have a place to sell, but I would still want it. I basically amassed a clothing rack in the bedroom of my studio apartment on Avenue B, and through word of mouth, friends would hear about it and arrive to take a look.

Soon, people who own vintage stores, professional cool people in New York, would pull up and honestly have to sit on my bed to rifle through the clothes. It was strange to me because I hadn't really advertised this, I didn't have an online or social media presence at all and people were finding out about me and looking through this rack of clothes that I just kind of stumbled upon or gathered as I went. Sometimes these people who would be reselling would buy the whole rack. At a certain point, I realized that maybe I should focus on this a bit more — or at least put a little more intention into what I'm doing and what I'm selling, and begrudgingly social media followed and became a requirement.

What is your relationship to social media and marketing your collection? How do you think that has affected the way that people are engaging with it?

In terms of my social media presence, it's kind of strange; I definitely do my best on some level, to convince myself to take pictures and post and edit and have a witty caption or something like that.

I also let go a little bit and realized that maybe part of what separates me is having a fair amount of my stuff be [only available] in person, and not posting all of it for everyone to see.

That’s easier for me, like the social media doesn't come naturally and I can be lazy about that stuff, but it also has felt more natural and bred this air of mystery or exclusivity for not having everything readily accessible online. Instead people have to come and make an appointment and then they can really see the full inventory here and get a full sense of what I have. It's been even harder for me when posting objects. I have objects and stuff that are beyond clothes, and with these kinds of things, I haven't really found a foothold or way to mesh them with my clothing that I put forward on Instagram. So for those kinds of objects especially, you’d have to see it in person.

My relationship to social media is that I begrudgingly do it. But I have realized that it's actually become kind of the selling point for me to not put everything out there for everyone to see.

How do you think that in-person only energy has created hype or a certain allure around your collection?

First and foremost, you have to have good stuff. No one's going to be intrigued to see what you're not posting if the things you're posting are wack. There's a delicate balance that I have stumbled into, where people are intrigued to see more.

I actually have people apply for an appointment, they can't just book one. And while all of that seems fairly gatekeep-y, it's also just because my showroom is attached to my house. So I don't want someone completely random or not super known in the industry just arriving at my house, for safety or privacy reasons. Word of mouth is also huge — being recommended that way has become its own monster where I don't have to do much advertising. Each time a new person comes, they become a walking billboard for it or advertise it on my behalf. So that's been really fulfilling to see it organically grow.

Who are some of the most exciting clients that you've had?

I've had Kanye's people reach out, and even though I'm a Jew, I’m a super fan-boy of Kanye. I have been an obsessive fan, like I had the Late Registration CD playing in my car for probably three years in high school. I didn't even take it out. That was very surreal. I didn't even believe it was his people when they reached out. I had to make them verify that to me, and in the end, he didn't end up buying anything right now, but that was very surreal just to have him reach out. [Editor’s note: since this interview, Ye has purchased from sumshitifound.]

I've had a fair amount of design teams come through. I had Kim Jones’ design team come through. They purchased an item that my dad had thrown on as a shawl when he wasn't feeling well when we were in France, which I had sourced at a flea market there. That was kind of fun, being able to call my dad who knows nothing about fashion to tell him that the creative director of Dior just purchased this thing. Although he can't fully appreciate that, I think he got the idea that that's pretty funny. Those clients have been great.

I've also really enjoyed working with stylists. Maybe initially, stylists reaching out didn't have the star factor for me just because I didn't know who they were, but after working with them, I’ve found that it's really cool to work with stylists and see where those things end up and how they put it together.

Could you tell me about the sourcing process?

I mean, the sourcing process I would say is half a hustle and half a sickness or an addiction. There really isn't a great way to source in New York City. The value in New York is on the selling side, 100%. There's fun places to source, but you're not gonna make money and you're not gonna find anything. It's just very picked through, everyone knows what they have and that's great. It's nice to live in a place like that for the purpose of selling.

For sourcing my stuff, it's so specific that I kind of have to cast a really wide net, which is time consuming. My girlfriend often would like me to be off my phone, but I literally am working when it looks like I'm just mindlessly scrolling. I have been through the antiques world, which I would also say is a big part of my life. I know a lot of people who are looking for antiques and if they find clothing that they think is up my alley, they'll send it my way.

That's a real lucky thing for me, to have many people who look on my behalf while looking for something else. I'm from North Carolina, so a lot of it's looking there when I visit my parents. I do a lot of sourcing in France. Beyond those places, which are the majority of it, I also look in the countryside, and through friends I've made along the way from buying one thing online and then getting to know them.

I don't charge a low price for my items. I do sometimes have things that aren't really my wheelhouse. I price things very fairly. It’s usually fairly high because the stuff is pretty unique and I see the value in it. And so a lot of times I price things at kind of an elevated price point, which is helpful for contextualizing it in that way. Pricing can also be a tool sometimes. I think I'm way more likely to sell it if I price it higher than if I price it lower — that's just how my market is.

I can command that higher price point for my curation and the consistency of knowing that it's going to be clean as well as destroyed, and wearable and all original. I don't modify anything. I like everything to be natural wear. That's a question I get a lot. Because of my curation and knowing it's gonna be legit and wearable and not disgusting, I can command a high price point also for being in New York.

And so because of that, I pay up. Something that's helped me in terms of sourcing consistently is that I pay up for stuff. A lot of vintage people like to sell stuff to me because I'm not lowballing them.

I really just price things at what I think they're worth. Sometimes stuff sits around for a while but someone's usually stoked to buy it just because if it's super unique, someone will get it and agree with me at some point. I'm happy to spend some time with a garment, use it for styling purposes, and then get it to someone that really, really loves it and is willing to pay that price point.

My main client is not a vintage person, nor is it vintage sellers. With vintage becoming so saturated, the majority of vintage sellers are selling to other vintage sellers, which is kind of an interesting phenomenon. There's more people that are “such-and-such vintage” on Instagram than people that just wear that stuff.

Most of my clients are higher fashion people, slightly avant garde, dressing people in a New York professional world, or just simply kind of a Balenciaga boy who wants the real thing. And so, instead of paying a grand for a hoodie, going to the source and getting the reference piece for 500 compared to the original, it's not that expensive. People in that high fashion world want a piece of actual vintage to juxtapose with the other stuff they're wearing. It just allows me to have a unique market.

ZAPPA wears GERMAN WORK KNIT (1930s), VINTAGE STERLING JEWELRY; ARIELLE wears FAUX-FUR LINED THRASHED OVERSIZED ZIP HOODIE (1990s), VINTAGE STERLING JEWELRY, holding 1950s SHOE SALESMAN DISPLAY BOOT

How do you evaluate value with the items that you're both sourcing and then also selling?

The stuff I'm selling values more subjectively, and that allows it to be a decent business model for me. Part of what makes both the folk art stuff I do and the vintage stuff I do exciting is that, ostensibly, the item doesn't really have a clear value, or maybe doesn't have much value at all.

If it's, like, a distressed ‘50s Levi's item, there's a book value there. But for these other things where I'm valuing it based on patina, character that I feel like is imbued into it, or just like a weird color which it's faded into which I personally love — you know, those things are pretty subjective. I can take something that, for someone else, doesn't have nearly as much value, or may have literally no value if it was thrown away, and I can look at it and say actually, no, this does have a lot of value. Either in an aesthetic way, or in a history way, or in character way, or in that it was really, really loved and cherished by someone. There's value imbued into it just from that.

Being able to be the avatar who recontextualized something in that way, and then commands that price, and puts it in the hands of someone who will really cherish it in that way — it is really rewarding.

Let’s talk about this lookbook. What does it mean to you to have something that collects and represents some of your work in this way?

Doing a look book and just having stuff photographed in this elevated way is really exciting. I haven't done something like this before. Having a fine art and auction house background and yet also doing the clothing stuff, I've always looked for a way to bridge the gap there. Doing clothing stuff for Antiques Roadshow is part of that.

I have some picture books that I'm trying to do, or I guess I'm doing at this point, related to clothing and capturing it in this artistic light. I also just had an event called Distressed Fest, which is what separates us from other vintage events; we have gallery style spaces and clothing hung up on the walls and it's about story and aesthetic value, not just like the collectible clothing value. There's a lot of these ways that I'm putting a foot in both the art world and clothing world. I'm like, how can I get these to come together in some way? And elevating the vintage to kind of like a higher fashion place.

It’s really exciting to see my stuff appreciated and taken seriously by a lot of people. It's also just really fulfilling, wanting it to sit just right on the models or wanting the right object to be placed by the models so that it brings out the characteristics of each thing. We're really trying to emphasize people seeing it in that way.

Vintage in a lot of ways was a way for people to dress differently and express themselves. That's kind of how it started for me in a way as well as just finding it while I was looking for antiques. It was also about dressing unique and not wearing the same stuff that all of my classmates were wearing. And I think some of that's been lost, and that there's now this vintage uniform. It’s such a big part of the fashion ecosystem, and that's great — there's so many people interested in it both sustainability wise and like in terms of the value of vintage pieces — and that also means that self expression can be a little bit harder to figure out.

As vintage has become more commodified and commercial, people are going to get into more beat up stuff and they're going to be looking for people that are kind of more specialized. That slow decline through deeper layers of, like, vintage hell is where we're at as the vintage market grows, people will keep looking to find something unique. I'm the deepest layer, where they'll end up, because what I sell is totally unique.

Photographs of models adorned in curated clothing and accessories are interspersed between tightly catchphrased posters (“TO MAKE YOUR LIFE MAGNIFICENT. ANYTIME. ANYWHERE”), campaign shots, and ephemera of the Hard Dressing ecosystem.

The work challenges the traditional notion of a catalog as purely pushing product — instead using the platform to integrate cultural critique, satire, content both fictional and real, and various personas including the “Fashion Critic” and “Dark Fashion Try Hard.” The guide is meant to help readers navigate the dark complexities of the fashion system, which ultimately, as Johnson explains, reinforces inequalities and furthers the issues at-hand.

A tangible extension of this vision, each page turns like a chapter in her ongoing narrative about class and identity. It harkens back to the world of K-HOLE, a similarly influential series of thought leadership publications released in the 2010s around notions of youth culture, branding, normcore, and contemporary discourse on style.

In March, Johnson introduced the world of Hard Dressing to audiences through a 24-hour livestream in a recreation of her mother’s salon during Paris Fashion Week, with special contributions from catalog collaborators Hugo Comte and Charlie le Mindu, as well as Yves Tumor and her commerce partner Basic.Space. A QVC-inspired reel by Éamonn Zeel Freel, a special poster, and mysterious tube of “PRODUCTS” accompanied the launch.

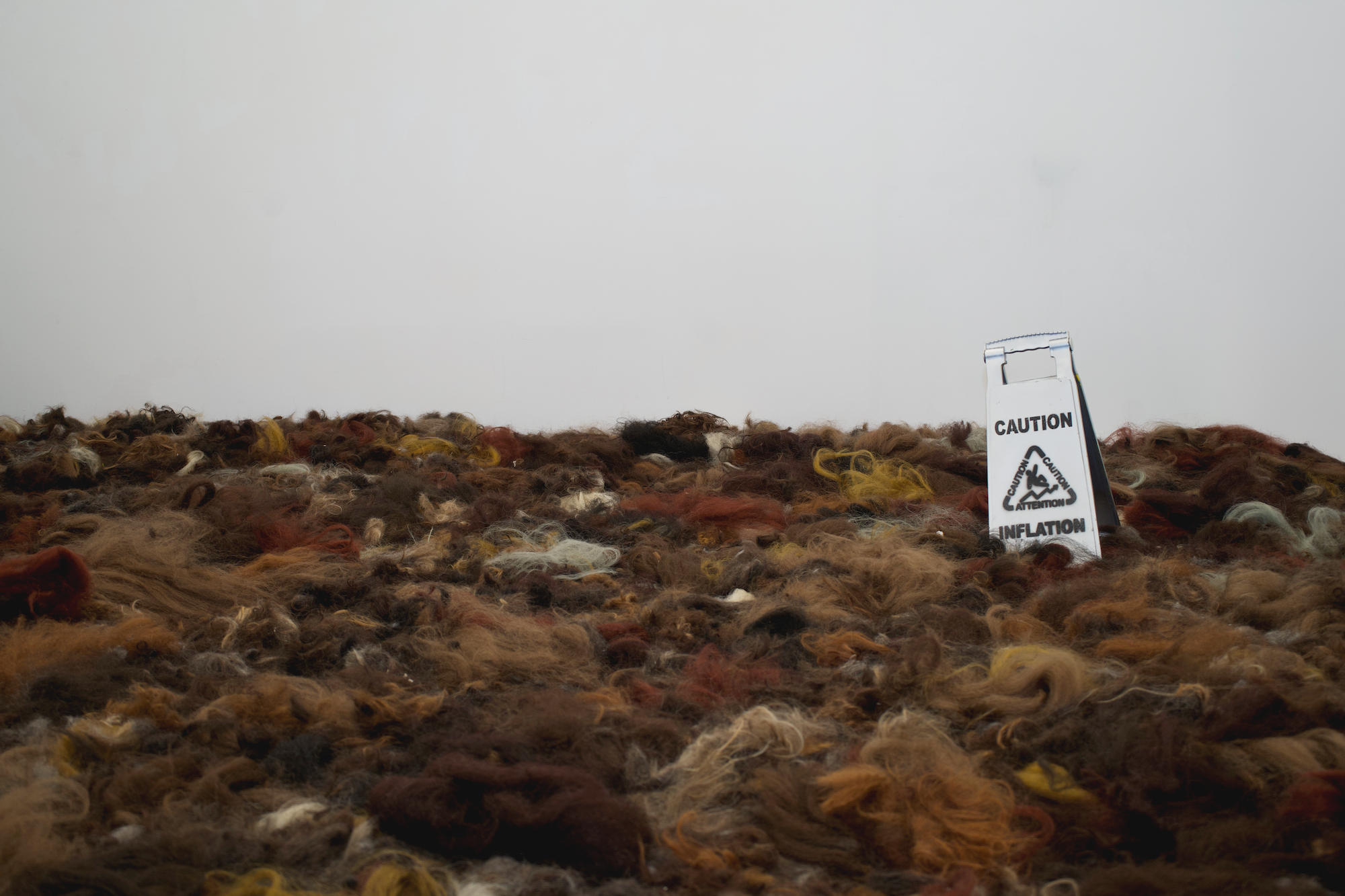

The follow-up to this initiation arrived in a June presentation at Paris gallery Sultana, where the concept came to life through a series of installations including a medicine cabinet of faux-bath products — “scaled-down deep fake beauty products referencing hair products and their relationship to Johnson’s coined ‘class camouflage,’” as the exhibition brochure read. A spray of human hair and synthetic wigs, sourced by set designer and frequent collaborator Rebecca Ilse from salons across Paris, was strewn across the space’s floor; "Do Not Touch the 'ART'" was scrawled across a column.

The multi-channel offerings of Hard Dressing speak to Johnson’s commitment to defiant, multilayered critique of the fashion industry’s complexities. In a sartorial landscape full of shifts both lamented and lauded — where the much-dreaded return of the “skinny” and dilution of heritage brands’ creativity in favor of sales coexist alongside a breathless assortment of buzzy emerging lines, and the creatives who support their endeavors (Johnson among them) — Hard Dressing emerges as both a voice of reason and revelation. “Ultimately this work highlights how consumerism and superficiality dominate our culture, offering little substance in return,” Johnson concludes in the catalog’s foreword.

We now await the next iteration of this project with baited breath, should there be one on the horizon.