Max Hooper Schneider: August 17, 2119

Hooper Schneider describes his new body of work through a fiction of the discovery of the Series, set 100 years in the future.

August 17, 2119

The technocratic climaxes of the World came and went. The present is more analogic than ever. It is not “dystopian.” It just is. It’s a polity of continental non-sites. No new “intelligences” other than those heralded a hundred years ago have appeared— e.g. thinking insects, sensuous marine invertebrates, motile plants, pigs trained to become telemarketers. No zombies, no steam punks, no road warriors; just the sempiternal breakdown and reconstitution of things no longer desired, or which hold no desire themselves. Huge tracts of cyberwaste became floating islands studded with bulbous cacti that burb powdered gametes. Rainbows formed in the scoria of sewers. Anhydrated fast foods and sun-dried French fries were used as geotextiles and building media. Garbology became the highest paid profession amidst the unending dross-scapes. The human species, before the severe physiological encroachments of mass delphinid mutations began, was stronger, more adept at survival, and exhibited higher faculties of reason. But thankfully there is less distraction now. The passions of modern society are gone.

I am becoming-dolphin, to borrow the phrasing of Deleuze and Guattari, two philosophers I used to read when reading was a possibility. I sit here in a tub of breast-high pinkish cooling salve that helps my body thermoregulate as I undergo my transformation, yet another round of nature naturing. Affixed to the rim of the tub is an antique TV dinner tray that I use as a writing surface. A crow delivers a hard-boiled egg for lunch in exchange for a glossy grub. Grubs are high value—in some colonies grubs have been fermented into a fine champagne displaying sultry notes of glass cleaner, desert potato, and sour tulip. Becoming-dolphin-crow-egggrub constitute a holobiont, a symbiotic association making our survivals interdependent and our bodies subject to one another’s evolutions. Every scientist or fieldworker should carry a grub and have a crow as a friend. The tub in which I sit is not only a bath but a mode of transport. It has rickety wheels and is equipped with a silent, chadri-clad attendant who pushes me from dig site to dig site, lab to lab. Between expeditions I look at the sky, which remains grey-black during the day. I recently saw a confluence of chem-trails that resembled an angel driving a monster truck over a nest of serpents feasting on the skulls of children. It reminded me of the wonderfully unintelligible album covers of the music of my youth, their enrapturing congestion, their perfect miscegenation of form. But nostomaniacal visions aside, I must admit, because of my rapidly evolving condition, reporting my discoveries has become quite miserable, but is, one suspects, a more attractive prospect than cloning or suicide. One can read Spinoza on nature naturing with extreme excitement and draw inspiration from his texts, but to undergo the ceaseless morphogenesis that I am experiencing at present is another matter—it is, to put it starkly, frequently horrifying.

Most notable are the cetacean-like transformations to my skin—rubbery to the touch, total reduction of sweat glands, loss of all body hair. It is perhaps twenty times thicker than before and has a translucent, pastel silver aspect. Fatty pillows of musculature are starting to fuse my neck to my shoulders and a turgid melon is protruding from my forehead and riding atop the bridge of my nose. Adipose tissue has begun to fuse my fingers and a coy cartilaginous blade interrupts the silhouette of my back. The angles of my body are being subsumed into a streamlined ellipse. It is becoming harder to talk, to wield words, conceptualize clauses, and my vocal folds feel as though they are collapsing under orbits of lard. I imagine an esophagus at a bus station holding a small suitcase waving goodbye to the nostrils and lungs. Something of a traumatic separation told from within my corporeal chambers. My vocalizations are high-pitched and squeaky, shrill like air slowly exiting a balloon inside a hermit shell. There is a hyperesthesia of hearing and vibrational detection. I feel before I see. I no longer sleep and am always conscious of my breath, but it seems I require less oxygen. Doormatsized sheets of skin slough off daily as new skin forms with origami-like precision. As I am not the only one exhibiting the delphinid mutations, some brazen individuals, typically traders and hucksters, have taken to eating the sloughed skin raw for protein supplementation, others pickling it for long journeys. I know there will be no cessation of the horror. Specialists consulted have indicated that my condition, my metamorphoses, will continue to advance, relentlessly, until I no longer resemble my human host in body or mind.

I am sick over divulging this information to my colleagues who may begin to doubt the integrity of my work. But if I am honest, I must admit that it is becoming more and more of a challenge to conduct the fieldwork that led to my celebrity as an archaeologist and fostered the far-reaching expeditions that defined my human lifetime. My time on land seems limited and thus I write in haste. My hope is that somewhere, sometime, there will be beings who can read and will be interested in what I have written. Reading waterbears with libraries haunt my fantasies and dreams.

Tampa became the southernmost tip of Florida after the Sunken City Pandemic that occurred over the course of the latter 21st century. All metropolises, suburbs, and exurbs are gone and the region is devoid of human life. Rafts of landfill, calcified plastic and speedboat fiberglass often embank themselves here. The landscape is quite literally a desertified archipelago of hellholes—fiery pits forged through tectonic disagreement, fueled by noxious gases upwelling from fissures in the Earth’s crust. Each one is more molten, more forbidding than the next. One noteworthy feature of the Tampa Hellholes, now the common nomenclature for this biome—the fires that burn are electric blue and arrestingly beautiful. This is caused by the combustion of sulfur, and until now could only be witnessed in Indonesia (now part of India along with most of Southeast Asia). Displaced, once indigenous people, fable that this is where demons, pained by horns growing out of their heads, come to die.

There is very little vegetation other than the monocultures of halophilic mangroves bioaccumulating the man-made synthetic oils that remain in the Gulf of Mexico. Up close one can observe that their prop roots are bejeweled with phosphorescent salt crystals, their leaves a distinct shade of carmine. In their canopies, aphids, from a genus whose transliteration is “Pompeii Pimple,” ooze trehalose like a slow-motion sneeze with the hope of trapping bloodworms in search of cryoprotectants. There are white rats everywhere; feral chickens and zebra octopi hide in acidic pools and prey upon them. Occasionally a metallic lily pad, pleather fanny pack or devil ray egg case will wash ashore. Astrobiologists studying extremophilic organisms liken Tampa to the vanishing fluorescent hydrothermal fields of the Danakil Depression in Ethiopia (now considered the Las Vegas of Africa). One can imagine the archaeological lure, the catastrophic treasures, the preserved marginalia that may be found amidst this biome. I did not know what to expect when I embarked upon this expedition and will do my best to appoint a description.

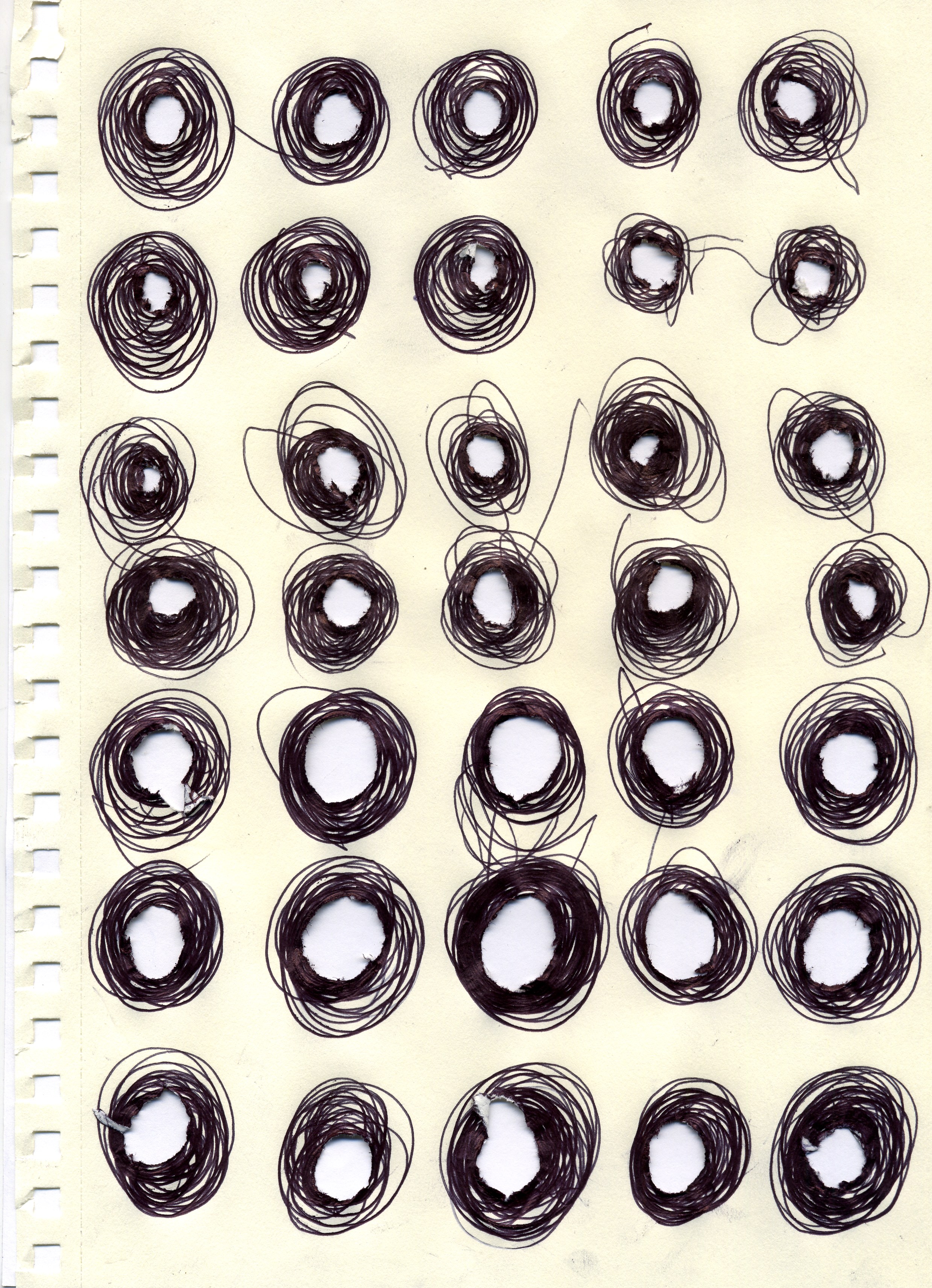

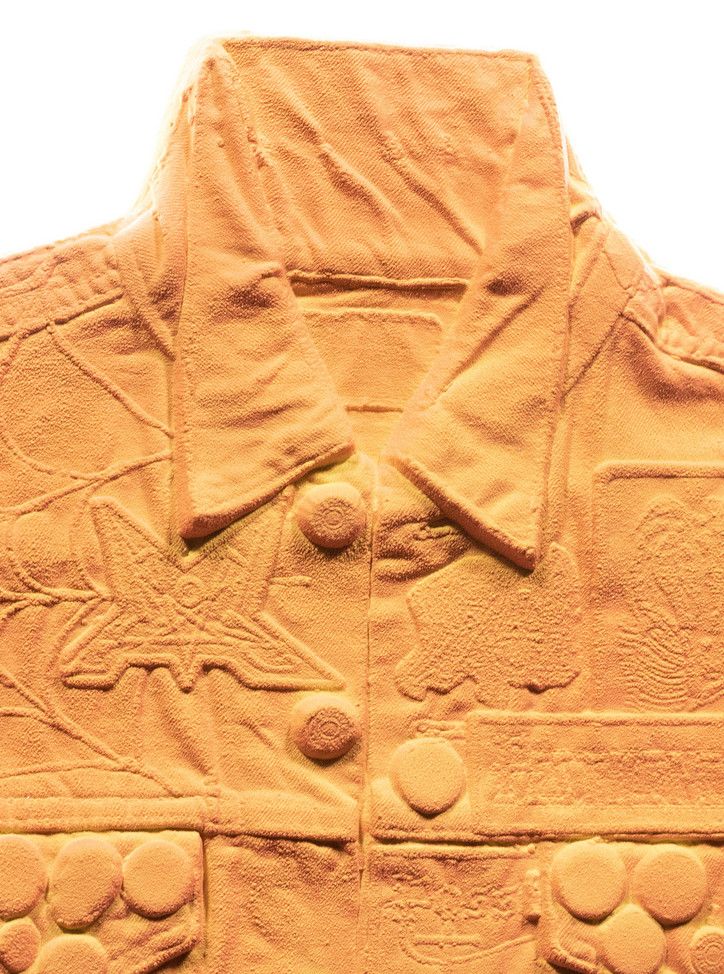

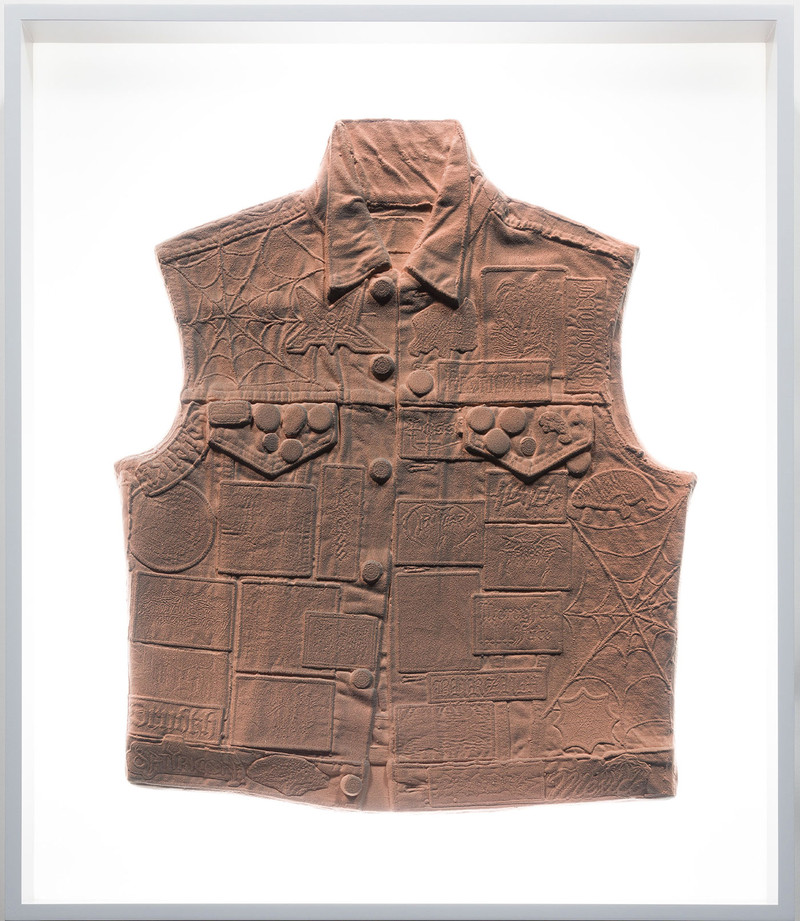

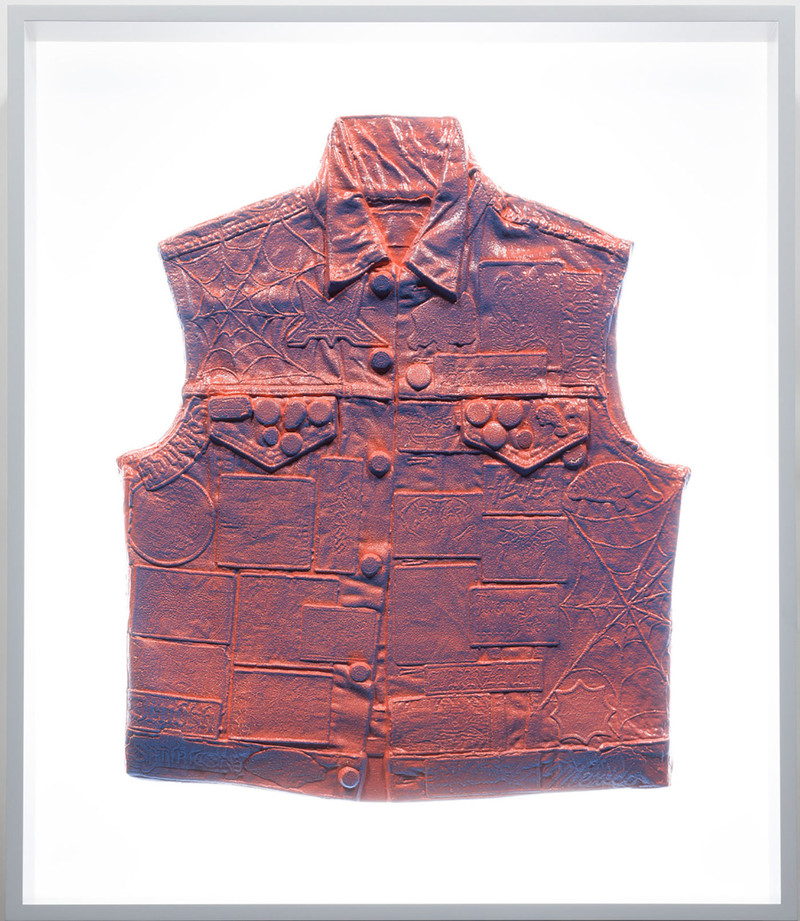

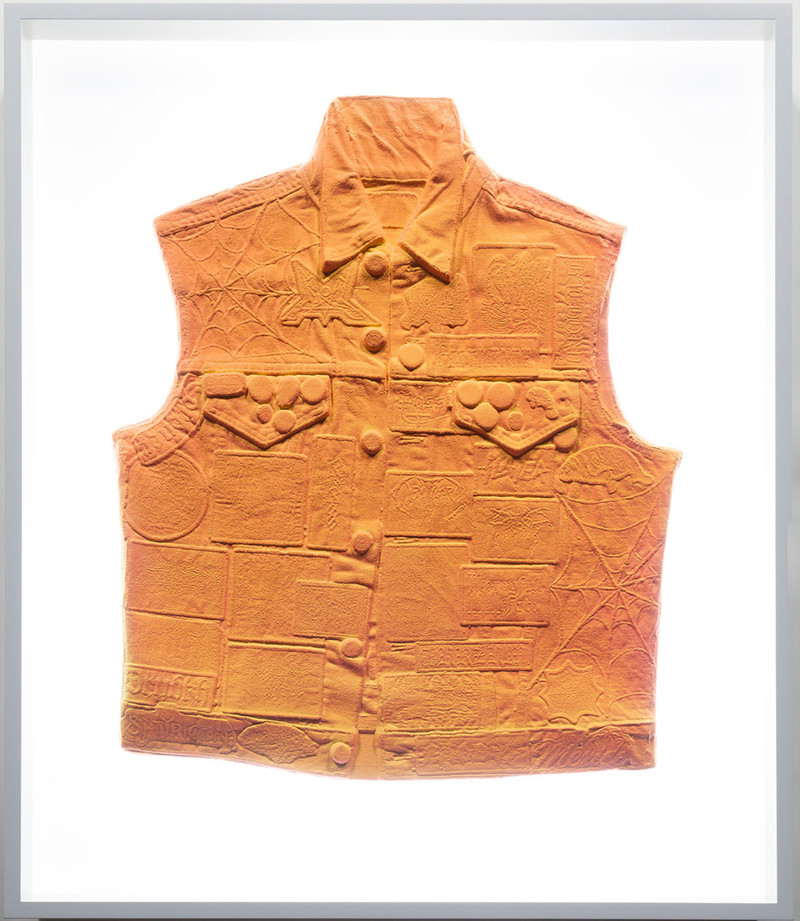

My discovery was serial. I’ve found close to a dozen artefacts. I believe they are vests, thickened through accretion. They are fossilized, scleratized, vitreous, and vary in color and physical aspect. Upon discovery they appeared tray-like, in the manner of pizzas in a tiered oven, along the inner side of a polychromatic, sulfuric arroyo that had formed beside a burning, lavatic landfill, its forgotten, reviled contents now hard and glassy, some dead matte, some like velvet, slippery and silken, its pile lustrous and capturing light in illusory ways, some effulgent and alloy-like. As columns of earthen detritus broke free from the arroyo wall, more vests were revealed. It was intimated to me by another researcher that prior to becoming a landfill in the 21st century, this was the terroir of an abandoned arena parking lot, and in a livelier age, prior to abandonment, the substrate of heavy metal (and associated subgenres of death, black, and thrash) festivals and/or titanic gatherings of the seminal death metal acts that secured Tampa as the American cradle of the genre in the late 1980s/early ‘90s.

How beautiful these slabs of kitsch. Runic neologies embossed in denim, bogus Biblicism, false mysticism, pictographic lettering, dioramic logos, imagined histories, bloody offsets, drips, sexualized gang signs, hackneyed verbiage further emptied of meaning: Obituary, Death, Slayer, Pestilence, Enslaved, Carcass, Exodus, Darkthrone, Coroner, Bethlehem, Burzum, Cannibal Corpse, Satyricon, Bathory, Deicide, Voivod, Drudkh, Summoning, Sepultura, Possessed, Deeds of Flesh, Mercyful Fate. They first register as worlds not words—this is the extraordinary accomplishment, testament to the powerful fantasy-energy the vests possess. Few poets, few artists, if my memory is correct, were capable of creating this instantaneous word-world event. I’ve also noticed the woven caricatures of a softshell turtle and a manatee—two creatures once endemic to the region. Embroidered spider webs creep into colonies of hem lines and band buttons. Each patch is a territory-in-itself, their confluent crazing mapping the literal, the absurd, the non sequitur, the esoteric. While their meaning intrigues, I am even more intrigued by attempting to imagine the kind of human, the kind of hesher, superfan, or mini-mall flaneur who brandished these sleeveless glyphic assemblages. Perhaps it was the bands themselves, their groupies or siblings or service animals who wore them, or mounted them to the walls of the dingy chambers of record stores. At any rate, I, becoming-dolphin, combined with the vests and they combined with me, an affective interaction, a mutual modulation of bodies, that allowed me for a time to experience what it was to become-vest.

The fascinations of the vests are multiple. Yet what continues to hold my attention is the technics of their creation, the nuanced morphology of fossil, the anomalous material in front of me. Each vest is, as am I, as is the Tampa biome, a trans-habitat— molecules colliding, combining, breaking apart, exotic mineralia vibrating inside the lightboxes I have used to preserve, display and study them. The fossils bring to mind Pompeii and summon Vesuvian paradigms. I also imagine moments of impact when atomic bombs were proven in the deserts of the American Southwest and a new mineral, trinitite, was formed. What sort of catastrophic, serendipitous event led to their creation in the Tampa region a century ago? A volcanic eruption followed by a monsoon of acid? A molten entombment unlocked by a boiling sea? Decades of cooling in soils saturated by heavy metal? A miscegenation or a mutant sequencing of all of these events? The soft denim and floppy patches are now ceramic, reef-like, rock hard yet are blanketed with a soft chalky substance, pubescent micro-topographies whose appearance is that of stained glass become opaque or stardust fallen on cremated remains. They have a strength and a delicacy unlike any other fossil I have ever seen. I have identified some of the contaminating elements, trash pigments, obsidian chunks of plasma-scorched garbage, and decomposed ort that have articulated their profiles: carbon blacks, chromium greens, forest ash greys, cobalt blues, manganese oranges and yellows, pollen pinks, rainbows of copper and iron oxide. The display has been completed but miraculously remains multivalent and shape-shifting, a dayglow coprolite, oil slicked upon stingray leather, a holographic carcass, an oblique blast radius from a radioactive explosion rendering a solarized specimen.

I too am part of the display. My mutational condition is worsening. My morphology, my texture and color, my Umwelt, my thoughts, are becoming-dolphin at an accelerated rate. I would like to say more but I must sign off for the day. I would especially like to relate further details regarding that most extraordinary event, the moment in which I experienced becoming-dolphin becoming-vest. Unfortunately, the event is far too complex for me to evoke accurately with the dolphin vocabulary that is slowly taking over my brain.

Max Hooper Schneider would like to extend a special thanks to the Saxe Patterson studio in Taos, New Mexico.