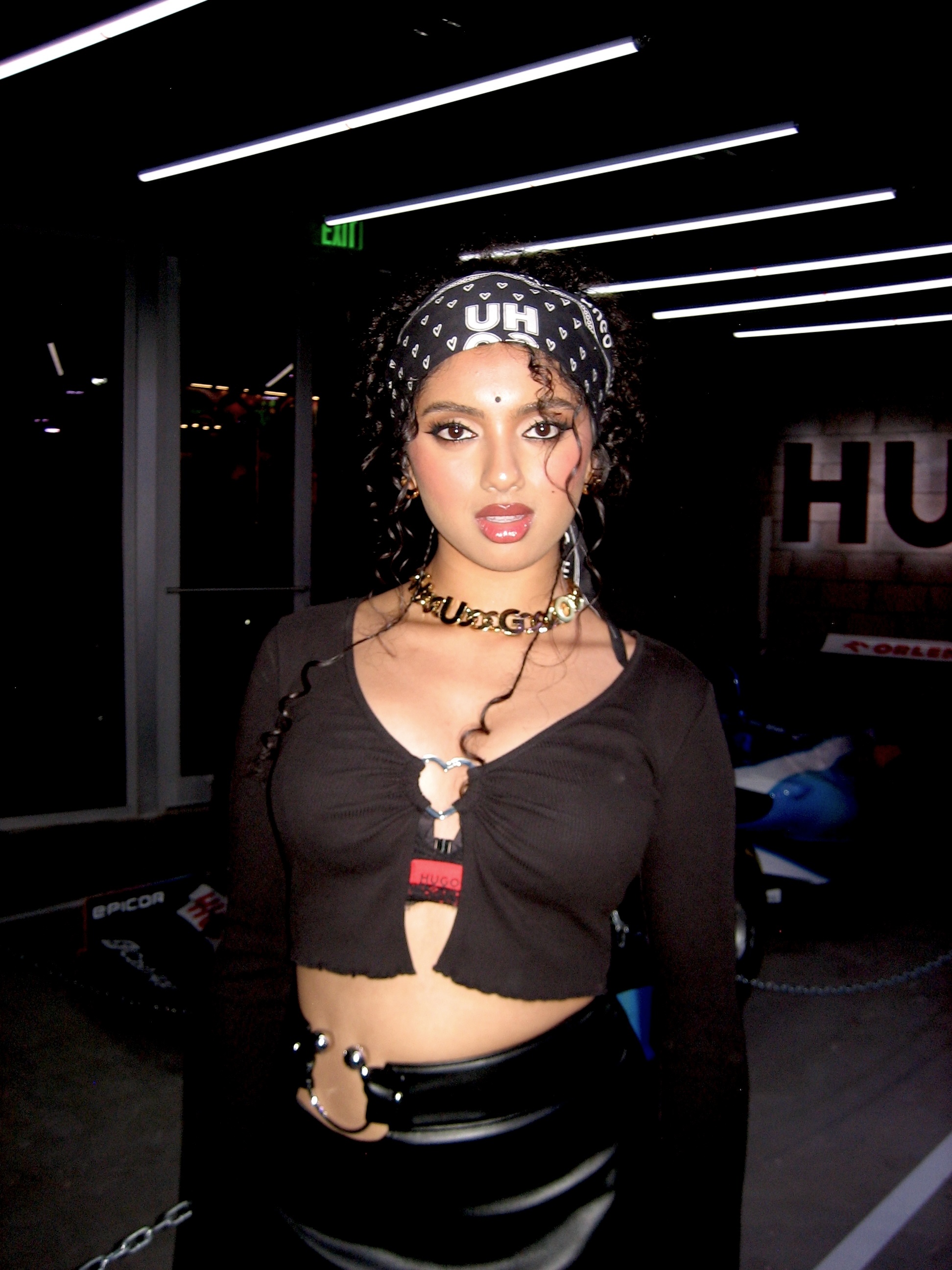

Why dance can get someone so riled up or triggered is perhaps because when you talk about 2-D art for instance, there is this separation from person and form. Some people opt to define a boundary between identity as an individual versus as an artist but with dance, you don’t have the opportunity to do that because it’s your literal body, you are the canvas.

MB— Yeah it’s living art and by definition it depends on people to carry it through. In cinema it’s the same but you have a recording that freezes in time. Right now, we’re reenacting what Lucinda Child put on in the 70s because we carry the flame so that it becomes part of the history of a different generations of dancers. In dance, we have no other solution than to do this. Of course, we can have recordings and we can mimic but the whole experience of space, time and it has to be re-lived, it’s quite special in this way.

One of the things that I wrote while watching A Room with A View was how trust can be a violent act. There’s a nuanced duality to it and you can see it in these dancers. It makes you recontextualize your concept of something.

MB— Right and even for me when I’m watching it I become shy sometimes because I cry a lot. I cry a lot for so many reasons but it’s really about the generosity of what the dancers are able to give because they trust the work. It’s an enormous gift to us, of course it's there for the

audience but I'm still very moved when I see this manifestation of how engaged their bodies are.

AH— They really want the audience to feel what they feel and what they give, they can never get back. The audience gives back by clapping and the moment of clapping is not only saying you did a great job or validating them but it’s more like, thank you. We very rarely see displays of pure selflessness and when we get in touch with this generosity, whenever we touch this movement of grace, it gives me trust in our humanity. We don't let ourselves activate it so often and we live in dynamics that are written around us that don't allow us to be grateful.

Routine is a chain. One on the one hand, you're giving them a space to tell their story but what is your story? How much do you share with them? Is it important for them to know your background so there is some sort of context for the empathy you have for them or is empathy just empathy?

MB— I think it is, I wouldn't know how to identify it but it’s what united us in the beginning. It was really this idea to give. It's rooted in the first project we did with MPAA (Maison des Pratiques Artistiques Amateures) where you go through a series of workshops and after 80 hours of workshops, you present a work. You have a group of 25 people you can create with and you have to deal with everybody's capacity, possibility, and knowledge of movement.

JD— This time we were with senior citizens, one of them was 84, one of them was practically incapable of moving and so we had to ask, how do you meet the other person not halfway, but 99% of the way? We nurtured this idea of care very much and we understood very quickly that it was really an emulation situation meaning that the more you give, the more you take back. It’s an escalation of good. Because our first projects were with these communities and the dancers were never considered to be people that would be at the service of our vision, we had to understand how to propose a vision to enter into dialogue with them. Sometimes they didn’t want to do things and we had to ask ourselves, how do you create consent? How do you work around everyone's personal boundaries? It’s amazing when they then began to process things on their own, it’s when things evolves

For you personally where does that come from in your own life? Everything more or less stems back to one’s concept of home and even you all have created a home within each other. You must have had experiences that were definitive for you.

MB— Well first, we're three. It’s hard to say because it's enacted very differently in each one of us. I try to expand it more than one person’s trauma that brought them to this and we’re not the only ones to do this. There was a tipping point where we felt the world was changing, even though we couldn't know how much, but we were teenagers when the internet became more profusive. I remember when we were students and YouTube became bigger and you could watch people doing everything or literally nothing in their living rooms. Jonathan and I were like, we’re so fucked. We were studying video and this was art, everybody was going to become an artist – which was great and what we want for society but where did we now stand? This is when we decided to make it our subject, to step back and look at what this phenomena was and the implications it would have in our bodies, in our relationships and how it would impact the way we move. There's this quote by Pina Bausch that says, I'm not interested in how people move, but what moves them. We're just very, very, sensitive and sentimental people and we wanted to find shelter because we felt that we needed protection so we created a house that would protect us.

Protect you from what?

AH— I don't know. The world is a pretty brutal place. When you want to show vulnerability, you have to have a good support system to handle the consequences of speaking out for anything. Even though people are fatigued by influencers or TikTokers, there’s a strength to expose oneself everyday doing nonsense. Because of the distance of being behind your screen, it allows people to be abusive or judgmental. We still want to be able to explore without being shamed for exploring.