Miu Miu M/Marbles

The Miu Miu M/Marbles Stool is available for purchase exclusively at the Miu Miu Miami Design District boutique and miumiu.com.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The Miu Miu M/Marbles Stool is available for purchase exclusively at the Miu Miu Miami Design District boutique and miumiu.com.

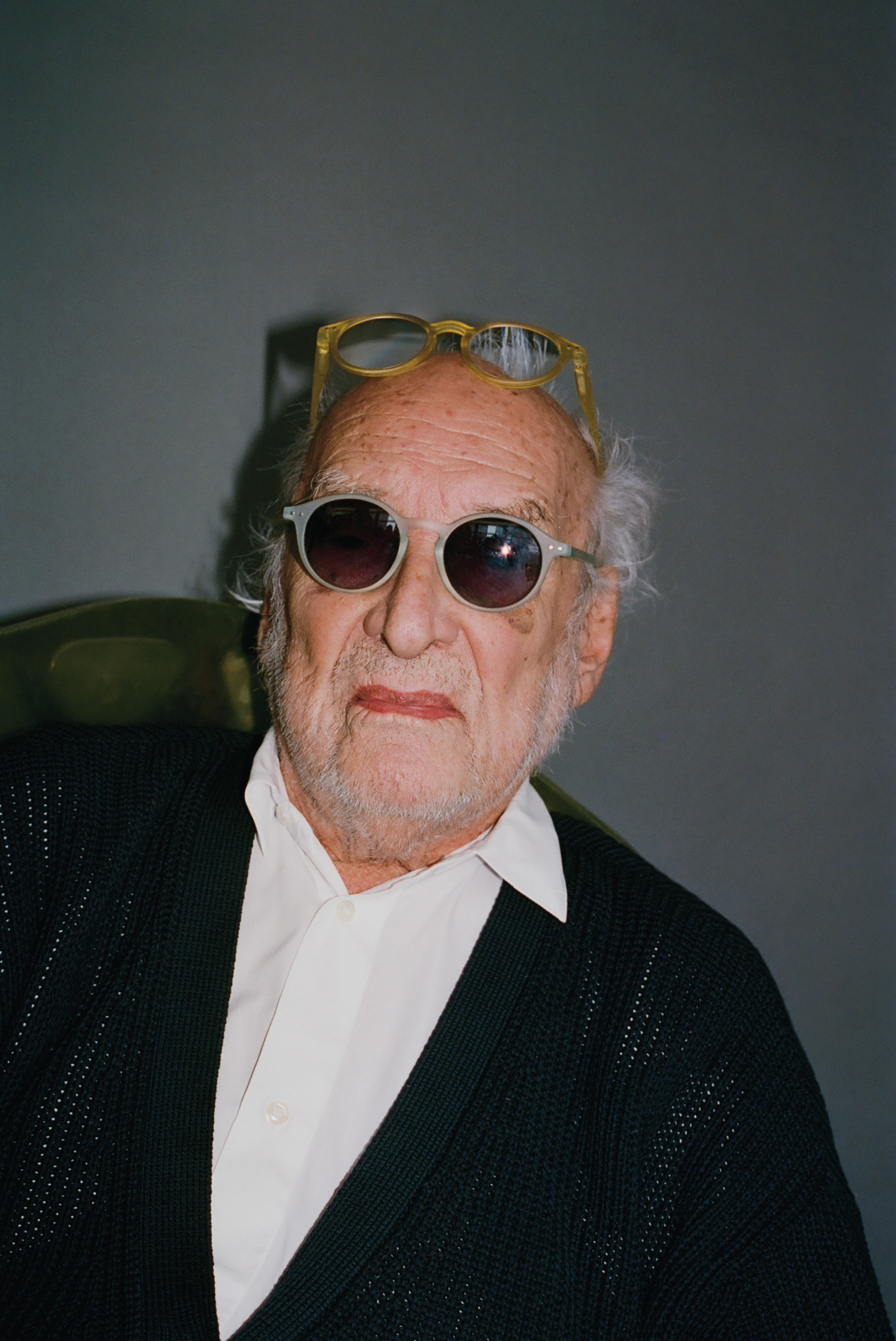

Gaetano has always been his own person, comfortable in spaces large and small, saying things previously unsaid or challenging the status quo even if just to say, “What if we tried something new?” From his early explorations in feminist furniture to a large-scale commission of dozens of chairs for Bottega Veneta’s Spring 2023 runway, his vision is singularly his own — undefinable, iterative, evolutionary.

At the end of the night when I finally worked up the courage to say hello (he’s a bit of a hero of mine), Gaetano inquired — peering over his eyeglasses — what I did for work. “A bit of everything,” I answered, laughing nervously.

“That’s the only way to live,” he responded. And how better to describe the work of a creative like Gaetano, whose design is as much art as it is sculpture or something in its own category completely?

office Editor-at-Large, Paige Silveria, and the architect-designer sat down in his studio to discuss childhood histories, the reality of time, bad art, and the melting pot power of New York.

[Originally published in office magazine Issue 20, Fall-Winter 2023. Order your copy here]

Paige Silveria— How are you doing today?

Gaetano Pesce— I’m depressed. No, I’m not depressed at all … but when I went out this morning it was very hot. So I was thinking in the car, “We are never happy.” If it is cold, we are not happy. If it is warm, we are not happy. So it is our human destiny to not be satisfied.

PS— What about spring and fall?

GP— They’re disappearing a little bit.

PS— Yeah that’s true.

GP— Next subject.

PS— Your childhood.

GP— It was very happy. We were very poor, but very happy. I had one brother and one sister and we grew up in the street more or less. There we discovered a lot of beautiful things, things that when you stay in the house, when you stay with rigid education, you don’t discover. When I was 6, 7, 8 we had no money for toys. So I started to make them. I had my own little workshop with my little tools. I very much enjoyed making boats and putting them in the sea. I’d add a pill to the boat because it reacts with the water to push the boat, so it would move. This was a discovery I made at the time. So that was my first workshop and when I first understood the importance of having one. If you have a workshop with the materials, you can verify if your idea is a good one. I’ve had a workshop all my life, like this one we’re in now. It’s very confusing but there is an order that everybody who works here knows. The visitor thinks it’s disorganized, but it’s very well organized.

PS— What was the town like where you grew up?

GP— I was the son of a navy officer in Italy, so we’d stay in different port cities. When my father disappeared in the sea, we moved to a little town near Venice. When it was time for me to go to high school, there wasn’t one there. So I moved to Padua, a very beautiful and important city. There I stayed until university. Then I moved to Venice for a school of architecture. Padua had the second-ever university in the world — the first was in Bologna — and Galileo taught there. In the 1200s in Padua, in the synagogue they’d speak in four languages. It was a very important intellectual center. In 1205, there was a rich man who commissioned a little chapel to a painter called Giotto. Giotto was a genius. He started western art. Before, art was Byzantine and in Padua, Giotto started Italian art, which is the western art. So it was very important to live in Padua, and to live in Venice. And then when I knew my country, I started to travel.

PS— Where did you go?

GP— I went to live in Helsinki for one year, London for nine months or so and then Paris, where I stayed for 30 years. Because I had no money, the French government gave me a little house to live in for free — in a garden. Also living there was a Moulin Rouge singer called Goulue, who was living with Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec — one of the great artists of the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th. We had the same house. Then in 1980 I came to New York because I considered the city one of the most interesting — if not the most interesting — where a lot of things happen that are not happening in other places. To be Venetian you have to know the world and I enjoy staying in the world of knowing and seeing people and places so I am here.

PS— What makes New York so interesting for you?

GP— This city has a lot of energy, because there are a lot of minorities who can keep their identity and the comparison between different cultures creates energy, vitality. They say that Shanghai is better than New York. It's not true at all because Shanghai’s culture is only Chinese so it's not interesting. Here there are a lot of different people, cultures, histories and identities. New York is really the city of the future. Diversity is visible. Nobody in New York tries to quantify the different minorities.

PS— You think that it's just as diverse now as it was in the 80s?

GP— Yes. It's still a very strong and lively city for different things. Also, the people living here are interesting; they want to create something innovative. In Paris, they are not like that. In Paris, they just live there. Little things like this can create consequences on the reality of the city. So France was great and Paris was great at the end of the last century when it was interesting for artists, writers, poets, et cetera. It was a very strong moment. But today for what I know, there is nobody interesting. They come here; I see them. I am sorry that you decided to stay in Paris.

PS— Well, I've got to explore the world just like you did! Take my time with places.

GP— So I talk a lot about diversity because imagine a world where we are all the same. There is nothing that we can exchange because we know the same thing. We like the same thing. We dislike the same thing. So being diverse is super important. Politicians who try to convince us that we are all the same, usually they are dictators. Look at North Korea, Russia, Venezuela, a little bit Brazil, China. They want to have the same people everywhere, which is totally wrong. Diversity of New York is equality.

PS— Absolutely. Can I ask, are you religious at all?

GP— Look, we are always believing in things. And me, I believe in what I do. If I have to think about the idea then the people think about God, this is not what I believe. But I have a strong belief in time and I consider time to be a very important presence in our life. Time. You know time?

PS— Of course. I mean, it can also be argued that time is an illusion?

GP— Oh no, no, no. It's very important. Time is who decides the way we have to live at this moment. And then tomorrow it tells us that this moment is not valued anymore and you have to change. So values are always changing and time is the one that changes them.

PS— Is it the catalyst for evolution?

GP— And it is also telling you that the value you were following yesterday is not valid anymore. If you follow that, you don't become old. You stay young. If you forget to follow time, your mind becomes old, and there are a lot of people who are not following it. Progress is the thing that you discover is better than what you currently have today. And if the discoveries are good, it creates progress. If we don't have the ideas for something new, something to provoke our intelligence, to understand and advance, progress, et cetera, we will stagnate.

PS— Which cultures, ways of thought do you relate to the most?

GP— The Italian. Better the Venetian, the place where they create a real culture which is expressive through presence of life, of light, of color. So there is a very strong culture there and a history of art without which our various existences would be very poor. So that culture, where I grew up — my father was from Florence and my mother was Venetian — is very important and I believe that signs of it exist in my work. I use color very much. I use light very much.

PS— What were your parents like?

GP— My father I never met because when he died I was only eight months old. My mother was a pianist and she taught me a lot about music, composition, why music represented time, et cetera. I learned a lot there. To me I was curious to know why an artist or pianist or composer is able to represent a special historical moment like Romanticism, like Impressionism. She explained why. She decided for me to go to architectural school because she said that that is where you learn the most important art, which is architecture. It is complex, strong, certain. I enjoyed it very much going to that kind of school.

PS— Did you have any really impactful teachers that stand out?

GP— The others were very mediocre, but I had one that was the History of Architecture teacher, and he was very good. He was able to talk about the past as if it were the present, explaining why a building created in the Renaissance had a certain quality. And he was talking about not the relevance of the style, but how to understand why an architect of the Renaissance was doing a certain architecture. He was able to explain what one had to do at this time. Kind of how to behave in our time, and what kind of architecture our time deserves compared to the past. So the school I went to in Venice was very good in this way.

PS— Do you have current plans to work on any buildings?

GP— We are doing a project that's a visitor center in the desert connected with a perfume company. I cannot tell any details …

PS— How do you approach a project like this?

GP— Everything starts with thinking, and I discover myself thinking quite a lot. Music helped me to think, to be innovative, to discover things, to use material that nobody uses — unfortunately for them, because it's very easy to work with my material, but nobody uses it. Thinking helps to understand our time better, what our time needs to be done, what we can do to allow the future to become present, and also have the present to become past. This kind of thing you can understand better with your thinking. And it's what I do. One important aspect of my work is that I don't like men very much because they are very boring. They're repetitive. They are a little tired today in general and I believe that it’s women who are bringing energy. Women have for a long time been obliged to stay in the private space, in the house, et cetera. Now slowly this is changing and this is very interesting. I believe there is a big crisis in the world because politicians are not at the level that they were in the older times. They are not doing the good for the places they administrate. They do the necessary for themselves and this is very bad. The world is in crisis for that reason.

PS— And women are the solution? I really loved Angela Merkel and Jacinda Ardern, the recent PM of New Zealand. I think they were extraordinary leaders.

GP— The future is that the women are moving from the private to the public and they are now working, as presidents, as leaders. The English lady, Thatcher. They are examples of great politicians who use their mind for the good of their country, not for the good of themselves. So this is one of the things I think about a lot, because I observe politicians and what they do in different countries is a disaster. Ukraine is a place with a lot of strange fascists, but they don't deserve for someone to make war on them. So I hope the women slowly take more and more responsibility in public life and they know how to serve better than men. The men in the older times did a lot of good things – important discoveries, communications. They invented things like airplanes, but today, they're tired; they play cards. They drink wine. I am not trying to see the future in this way, but I think in 100 years women will be directing public life better than men.

PS— Tell me about your book, The Complete Incoherence, and its title.

GP— Since I was 18 I’ve said I have the right to be incoherent: meaning, I say one thing today and I say a different one tomorrow. This is a way to be free and not to think always in the same way, like the military. I’ve always been incoherent and I’ve enjoyed that very much. Because I feel that I can experiment, and then say I was wrong.

PS— You seem very confident in yourself, very self-assured. Have you always been this way?

GP— I am not. I am totally insecure. Because the incoherence gives you insecurity. But who cares? Me, I am what I am. And so I don't want to say, "Look, this is the truth. Do this. It will be okay." No, I don't think so. Everybody has to learn how to swim. No regrets at all. Also because sometimes we say we don't like problems. No, problems are part of life and make your life interesting. If everything is easy — like in Scandinavia, where they have a very good administration, I think people are not totally happy. Where life is perfect, it’s also boring.

PS— Can you tell me about your proposal for the bridge project between Italy and Sicily?

GP— Someone proposed a project that looks like the San Francisco bridge. And I said, “Look, Italy is not a country that copies. It's a country who is copied.” And so I made my proposal, which is a bridge that is not straight from one point to another, but an S-shape. And there are 18 pillars, and you go with a train or with a car. Within the pillars, there are showrooms representing the 18 [20 minus the two on each side of the bridge] regions of Italy. Each has a hotel, a restaurant and a showroom inside. It's not that you go from one point to another in three minutes. You go because you stay in this hotel with a beautiful panorama at the level of the sea. It's what we are trying to show in Italy to make an exhibition. Not because I believe that they accept my idea, because it's too difficult. But at least I provoke people into thinking that there is a possibility to do a beautiful new idea of a bridge.

PS— I wish you could see more innovation like this realized!

GP— Yeah, sometimes I go to see art shows, and I find them a little superficial and the quality, nothing really innovative. I wonder if art is in crisis.

PS— When was the last time you saw an exhibition that you really loved?

GP— I don't know. I saw the guy in the London Museum of Art, who put a big fish inside liquid — Damien Hirst. You can show that in the Natural History Museum, not in an art museum. Or another one that I know personally is a guy who makes a kind of bean in metal, very shiny like a mirror. The people go and see the form and say, "That you do in the factory, not in the art studio.” There is very little meaning, because you don't need a lot of artists. In each era, three or four is already a lot. When I saw Duchamp for the first time – he's a great artist – there was a lot of meaning, a lot of ideas, a lot of innovation. We remember his work as something important; Duchamp took some industrial objects in 1919 and he put them in an art gallery creating a kind of scandal and a shock to let people know to be careful because the art today is related to the object, to industry. It’s like the Surrealist and the Futurist did. The Futurist celebrated the production, the machine, the noise. That was really an innovation, a movement. Today I don't see people so radical. If you ask me, I have no idea. Maybe I am ignorant.

PS— What does your home look like?

GP— It's a very simple place. Where I can live is a tool; nothing special — no style, no nothing — with a beautiful view of the water.

While the digital medium has faced skepticism within traditional art circles, Pantone's innovative approach challenges preconceived notions, highlighting the evolving landscape of artistic expression in our current era.

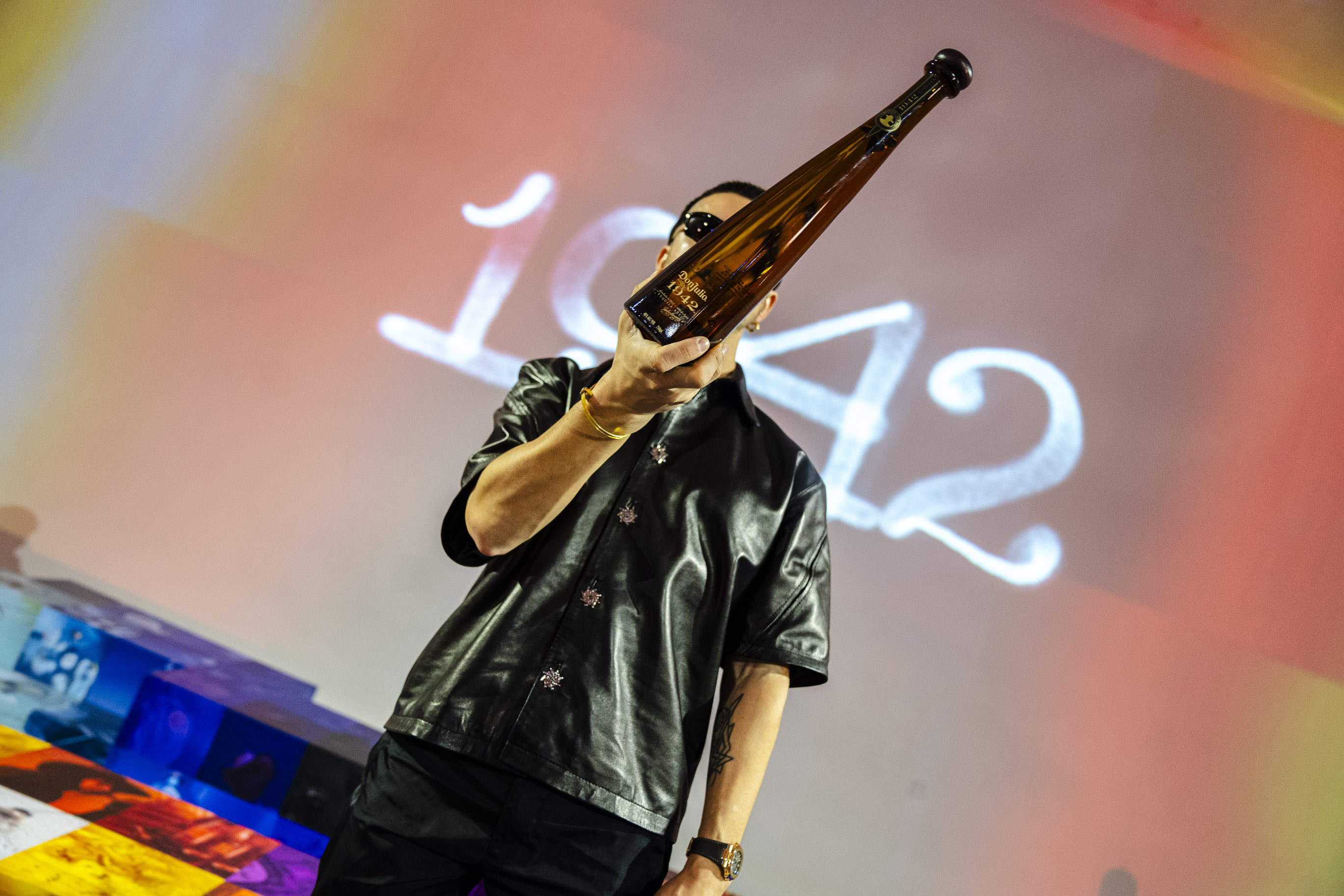

To enhance the immersive experience, Gochez was present at the exhibition, engaging with attendees through photography and conversations, shedding light on her integral role in bringing the project to life. The collaboration between Pantone and Don Julio was a nice addition to the week, showcasing how the digital realm can breathe new life into traditional art forms, ultimately bridging the gap between the old and the contemporary.

Over the weekend, we caught up with Pantone to delve into the details of how the project came about.

So what intrigued you about merging kinetic art with a tequila brand?

Mexican culture has influenced so many aspects of the art world and beyond, so I was thrilled to partner with Tequila Don Julio to invite guests to celebrate modern Mexico through new visual mediums that celebrate the country's heart and soul — paying homage to its people, culture, and landscape — in a truly unprecedented way. I was deeply inspired by Tequila Don Julio’s latest creation “Por Amor” (For Love) which is a bold and vibrant "Love Letter to Mexico."

Through kinetic art and digital expression, I was able to bring their new visual world to life and guide attendees on an immersive journey into the vibrant heartbeat of modern Mexico that I’m thrilled for everyone to finally see in Miami.

How did you translate the concept of the love letter into your artistic practice, especially considering it was Don Julio's brainchild?

I pulled inspiration from the incredible visuals that have played a pivotal role in this campaign to authentically tell the story of Mexican people and their culture through a creative lens. This exhibition reimagines this story through new mediums and experiences that invite viewers to perceive and appreciate the profound significance of capturing a nation's soul and elevating it onto a global stage.

How was working with Thalia Gochez? Tell us about how it all came together.

It was an honor to work with Thalia Gochez, a Mexican-American photographer who captured beautiful visuals for the "Por Amor" campaign that represent the magnificent culture of Mexico. These images take a new form in the exhibit as I incorporated them into an interactive sculpture that guests are encouraged to connect with. Participants are encouraged to become integral parts of the living art.

Can you elaborate on how you designed the exhibition to achieve this element?

There are two key elements: one is the immersive projection mapping experience that surrounds the spectators. The other is the Chromadynamica sculpture that integrates the Thalia Gochez photographs. The guests are encouraged to walk, sit, have a drink, or simply hang out on it.

What do you hope attendees take away and think about?

I want them to experience the art, and connect with my idea of dynamism, but also take a breather from all the art fairs, sip on Tequila Don Julio, and enjoy art in a relaxed environment.

Was it always the plan to have her photograph attendees?

Yes. It was an honor to have Thalia Gochez capture the event with the same touch that she captures the essence of Mexico.

The collision of an analog past and digitized future is a recurring theme in your work. How do you navigate this intersection, especially in the context of Art Basel when the art world has historically had a bit of an aversion to the shift?

The digital age is here. The art world doesn’t necessarily need to embrace it in a literal way, having art fairs only display art that only lives on the internet such as NFT, but it’s a good idea to keep an open mind, and to use new technologies to keep art and creativity moving forward. That’s why I feel that my work sits in the middle of those two concepts.

Are there any other exhibitions you suggest people check out if they liked this one?

Art Basel, Design Miami, Untitled, Nada, Rubell Museum, Superblue.