Nightmare Hack

Read our interview with the filmmakers, below.

Can you tell me a little bit about crafting the story together?

Isa Mazzei: I studied literature at UC Berkeley and wrote a lot, and I studied futurism and the avant-garde. So, when we started talking about doing a film together, I brought a lot of my literature background. And Danny—he went to film school—so he brought this cinema aesthetic and idea to it. We built the story from the ground up together—when we say it’s a film by us, it’s a film by us. Everything we did together.

We’d have these long conversations about story or about my experiences camming and what we wanted to bring into the movie and then I’d go and bust out some pages, and then we’d talk about them. We had this nice collaborative process from the beginning that let us build this trust with each other that we then took onto set.

Why did you decide to go with horror as a genre for a movie about a sex work story?

Daniel Goldhaber: Originally, we were thinking of doing a documentary on Isa when she was camming and ultimately ended up feeling that pornography and documentary have a very similar contract with the audience—and that contract is like, voyeuristic, ‘I’m giving you reality.’ And docs are not real. They’re still crafted and there’s still a point of view. Documentaries are very hard to make about someone’s psychological reality. And that was very important in this—really bringing an audience into a camgirl and a sex worker’s psychological reality.

So, we quickly abandoned that, and came up with this opening scene and realized there’s a surreal psychological thriller in here. But when you’re thinking, ‘How do I build familiarity between an audience and a sex worker?’ Genre is a great way to do that because genre is familiar. So, when you take ideas like those in CAM that are subversive and fresh, both when it comes to sex work, but also when it comes to the portrayal of technology and you bake those into genre structure, you allow an audience to feel familiar with them.

How did you keep your story intact when switching from the idea of filming a documentary to horror?

Daniel Goldhaber: We had a manifesto very early on with our non-negotiable rules and ideas for the film. Our number one rule was that the audience has to be empathizing with the sex worker and the negative stakes of the movie can’t be derived from her decision to be a sex worker. So, if you think about it, the horror twist of the movie is a sex worker’s loss of agency over her own body. And that only works if the audience realizes that she did have agency over her body in the first 25 minutes of the film. So, that’s where the stakes come from, even if it happens retroactively.

So you guys considered doing this as a documentary at first and Isa, you have a memoir coming out next year that has to do with camming. When you were working as a camgirl, were you aware of how much creative work it would later lead to?

Isa Mazzei: When I was camming, camming was the creative work. My cam shows were my creative outlet, my art. All this creative energy that I’ve always had my whole life that I put into different places—be they my bad novels, or in this case, my camming—that was the work I was really proud of. That was where I was getting my creative validation and my self-expression. So, when I started writing the movie, it felt really natural to put those creative energies into a new medium and see where that took me. I’m really excited that it opened this door to making movies with badass female leads.

Were your shows similar to Alice’s where she’s doing these very theatrical, themed shows?

Isa Mazzei: Some of them, yeah. Some of them were just straight porn shows, and some were more experimental. Just like Alice, I was very studied in my shows and I tried different things and saw what worked, saw what audiences engaged with and did more of that. So, I did many different types of shows—some very creative and crazy and some I would be just masturbating or playing Jenga. It kind of ran the gamut.

I know averting the male gaze was important to you both, so I’m curious in making the film—in staging it and in writing it—how did you avert the male gaze?

Daniel Goldhaber: It was a process from the first moment to the last moment of working on the film. Even when it comes to the authorship credit, this is a film by me and Isa. We frequently think of authorship in film as a monologue from a single, predominantly male person. In this film, we really wanted the film from an authorship standpoint to be a dialogue. And a dialogue can be I’m a man and Isa is a woman.

In many ways, my impetus for getting involved with the project on a personal level was that it came at a time when I was reckoning with an unhealthy relationship I had with the women in my life and the way I had been socialized to behave around them. I wanted to re-educate myself. And this film and working with Isa was an opportunity for me to learn from her, and I’m very thankful for her patience in that capacity.

Isa Mazzei: Also, in thinking about stripping the male gaze from a film, we’re dealing with this legacy of cinema that objectifies women. It’s been a male-dominated industry since its creation. So, we had to be very deliberate in every moment to recognize when standards of filmmaking were catering to the male gaze, sometimes unintentionally.

What scenes in particular do you think create an opportunity for a man to learn about relating to a woman and her sexuality differently?

Daniel Goldhaber: In many ways, the Vibratron scene is one of the best examples of that, and the loss of agency. If there’s a third, it’s the craft that goes into not only sex work, but performed gender in general, performed sexuality. We really treat the performed gender that we encounter of both male and female as a given in our society and it’s one of the more toxic components of our gender paradigm.

How does Barney, the male character with a lot of toxic masculine energy, fit into that?

Isa Mazzei: Barney is really a stand-in for male entitlement over the female body within the patriarchy. Men feel entitled to female bodies, especially with sex workers. Often men decide that if they pay you for one thing, they’re entitled to everything. And that’s absolutely not the case. Sex workers have boundaries, rules and prices that need to be respected. Initially, he doesn’t come off as a bad guy, just a big-shot tipper. And then there’s this shift all of a sudden where we realize he thinks he owns women because of his wealth, power and status. The #MeToo movement is so indicative of these paradigms we’re living in.

Is this sort of identity theft something that cammers really have to worry about in their industry?

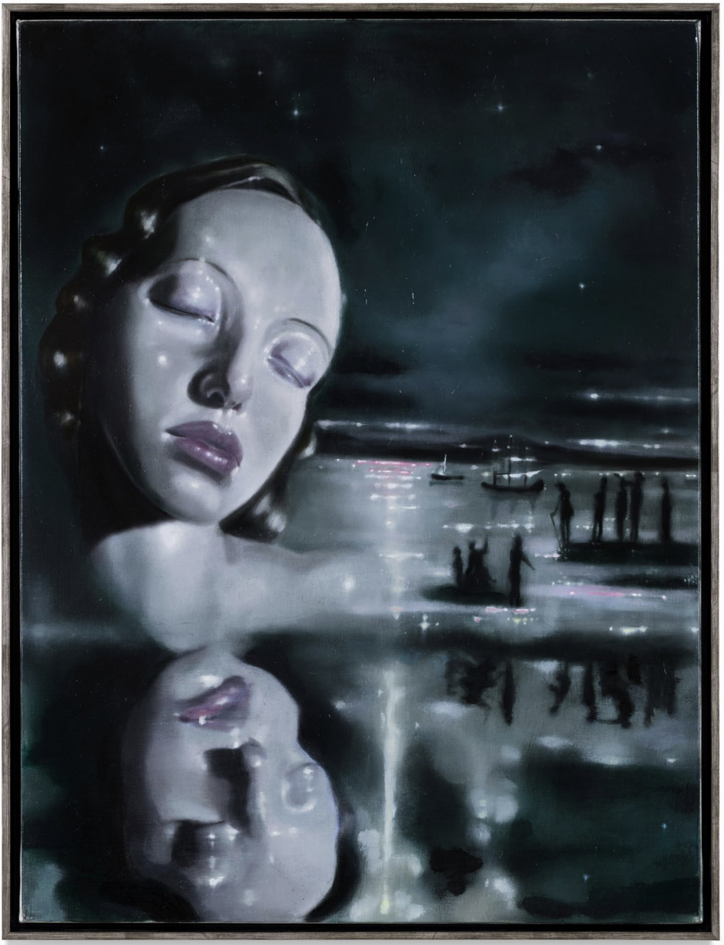

Isa Mazzei: I think anyone who engages with the internet has to deal with the threat of identity theft. On a more literal side, Lola is the embodiment of some experiences I had as a camgirl, but also of what a lot of us have had with curated digital identities. We all put a fake version of ourselves online. We all have a digital persona that we’ve built for ourself. No matter how real we want them to be, they’re still, by definition, curated. So, there’s always a paranoia when you’re getting validation from online platforms, ‘Do my friends actually like me? Do they just like this digital persona I’ve created? Where do I stop and where does this digital identity start?’

Another real experience for me was having my work pirated, screen-captured and posted all over the internet often without my name on it. I’d see myself on a porn site naked and it would say, ‘Frizzy-haired pale girl does X,’ and I’m looking at it and it’s in no way tied to me anymore. And it was really a disembodying, alienating experience to look at myself, but myself was no longer tied to me in any way. That experience, and feeling that kind of violation and alienation from myself and my own digital persona was absolutely something I drew on to create Lola.

Watch 'CAM' on Netflix now.