No tears for the creatures of the night

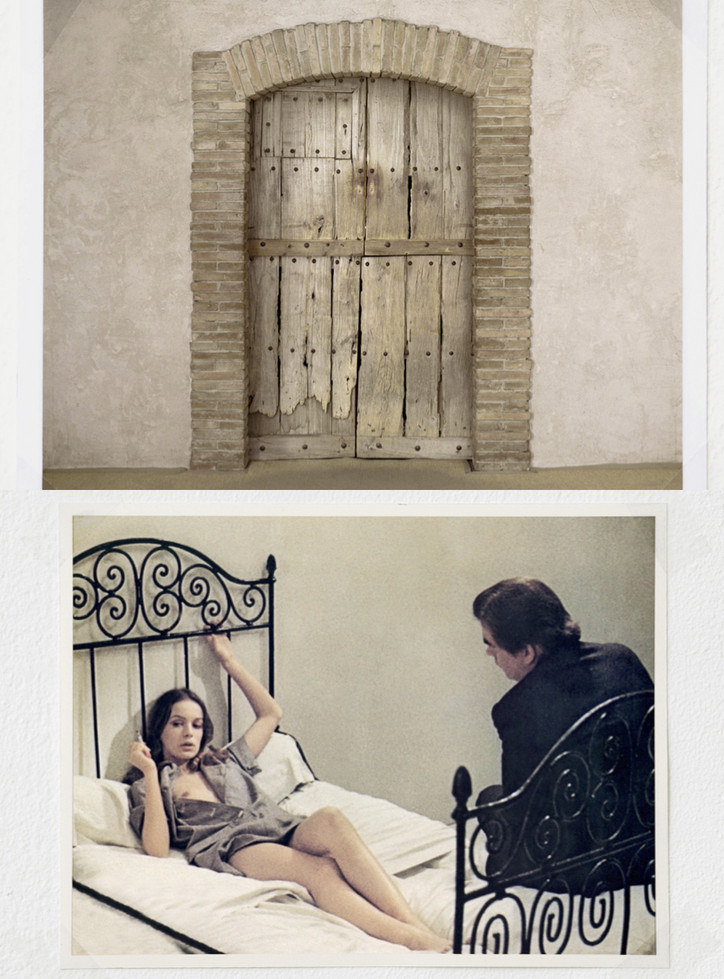

Like an audio will-o-the-wisp, the voice of French actor Frédéric Fisbach leads the audience through the huge industrial walls, drifting from speaker to speaker. The voice recites Alain Robbe-Grillet’s bizarre description of a Gustave Moreau painting that never existed - a commissioned piece of writing called, intriguingly, "The Secret Room."

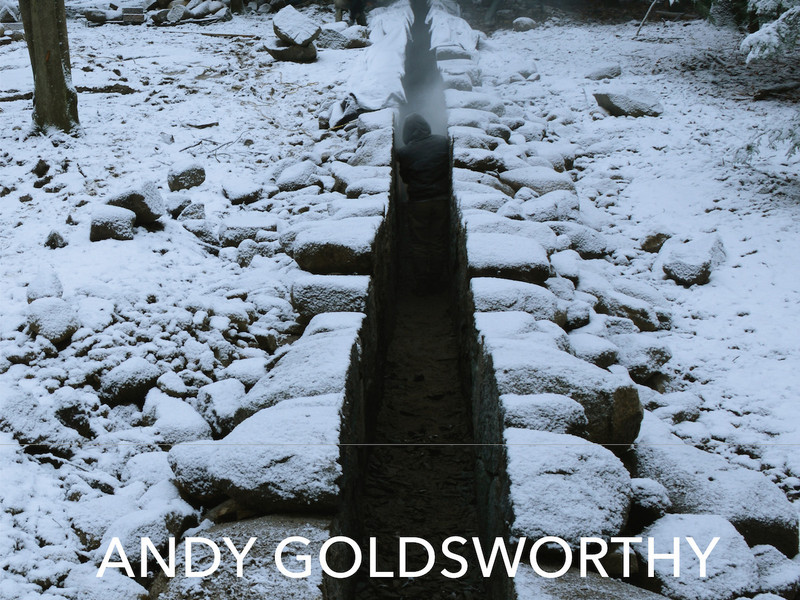

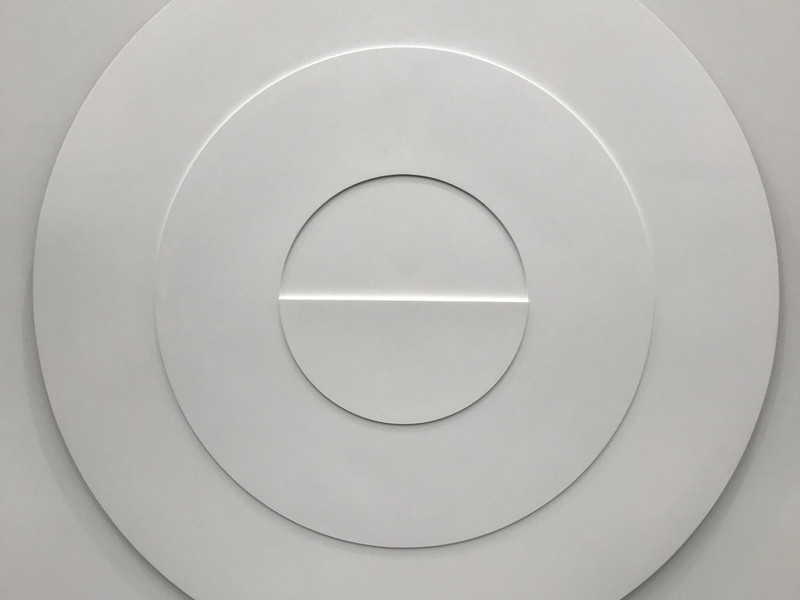

Three monumental abstract sculptures dot the space, and white florescent lights cut across the ceiling diagonally while natural light floods the room, creating an immersive liaison between light and sound, structure and audience, architecture and literature.

So there’s a live performance element?

The name of the Biennale is Floating Worlds, the idea was to have something kind of atmospheric. The idea started with the stage - but also you know it’s one of the most expensive things to provide in the art world, a live performance. So we took this idea of literature, of theatre, but of course we realized quite fast that we should make something recorded. The idea was to have a stage and we had the whole, complete floor of the building. From that, the literary piece is a kind of structure associated with classical structure, so from this idea of the stage and theatre we created a kind of architecture that is almost empty. We added some sculptures and there are layers, one of the sculptures comes from the collection in the museum in Lyon, and the other came directly from the house of the artist [Untitled by André Bloc], it’s a very important sculpture from the last century, and creates a connection between all the related fields like architecture, design, and so on. They add layers to our understanding of them as cultural objects and the experience of the environment of the architecture.

So… there’s no live portion?

No, there are seven speakers, which progressively create a subtle movement in this space, the idea was not to fill the room with sound. It’s like a walking voice through the space that you follow.

How did you land on "The Secret Room" as a text?

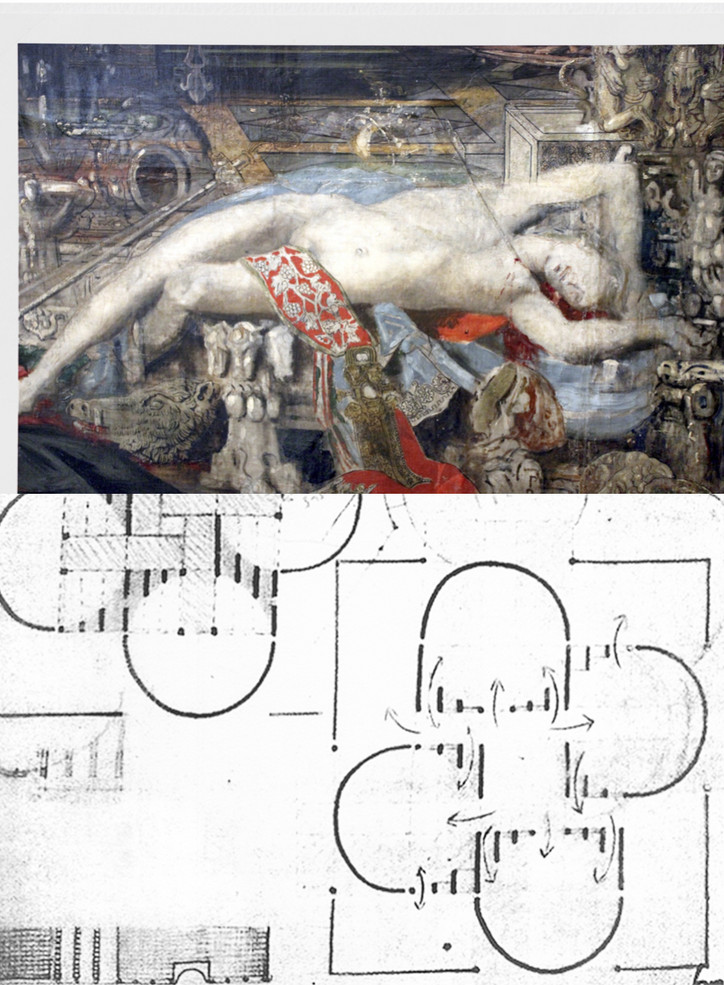

We discovered the text from a conference from the seventies and one of the composers from this period was a producer and companion of Robbe-Grillet and he wrote a lot of music for his movies. What was interesting in this conference was how he described the way the piece was written, he was not so interested in finding an interpretation related to the content of the story itself related to the sexual obsession of Robbe-Grillet, an obsession that was common with Gustave Moreau paintings. He was interested in the structure of text as a piece of music. He was commissioned with other writers to write about an art piece, and Robbe-Grillet chose to write about a painting that never existed, by Gustave Moreau, who is a famous painter related to mysticism and symbolism and all that. And of course the painting has themes of crimes, sexual crimes, which are aspects in a lot of Robbe-Grillet’s works. It’s interesting because the text itself is a description of a painting, but not exactly. It’s a crime scene. It’s very clinically described, it’s not disgusting but it’s very clinical. It’s interesting not only in what it describes but how it is described, there is a kind of structure like that of music, it’s like an opera in three parts, there’s a symmetry - always this question of symmetry. So it was important for us the way the performer read it, to capture its relation to music.

That was actually one of my questions: is there a connection to music? Because your work feels very rhythmic just from looking at it.

Yeah, totally. For a musician everything is music, and for a psychoanalyst everything is about psych. So for us we see structure, even when it is about music.

You have an obvious interest in light. How would you define your work’s relationship to light, and do you prefer natural or artificial light?

You’re right, it’s an obsession with light. It’s funny because every project we don’t decide to avoid it, and we don’t say we’re going to play with light one more time, one more time - no, it always just comes back. So the idea here was to have artificial light like in a museum, and this layer of light is almost like a structure itself. You can see in the plan the density of light changing, so theoretically we have a different amount of light from one side of the room to another, related to different conservation techniques in museums, in theory providing a variety of light. But we were happy to discover that there was a window wall that let in a lot of natural light, and we were happy to have a mixture.

Your work often engages with the past, how would you describe your work’s relationship with the past?

With this piece we were specifically engaged with the past, but it’s not something we necessarily gravitate towards every time. We can make a new piece from other cultural pieces, something from the past - I think we can make a new piece from anything, maybe we show that you can pretend to make a new piece from old pieces, what’s new is the relation between the pieces. So we can create a found structure, the structure itself isn’t so important as the idea. The label is not important. We pretend to make something new with a lot of things that are historical.

It’s pretend, I like that.

Especially with the Bienale there’s always this question of what’s new, what’s new, what’s new, but a lot of the exhibiting artists are dead, so I don’t know, it’s kind of surprising and radical to include so many artists who are dead, who are historical figures. So we decided to include some pieces from dead artists that were not included in the curator’s list. It’s like we’re curating within the curation, some people were saying it was a Bienale within the Bienale.